Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

Six Great Ancient Libraries: Humanity's Lost Knowledge Hubs

A journey through history's greatest libraries, from Alexandria to Baghdad. Discover lesser-known facts, challenge misconceptions, and explore the ancient world's dedication to preserving knowledge.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-7 | Last Updated 2025-07-7 | Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

This article has been visited 4,699 times

Artists impression - Scribes at work at Alexandria

Six Great Ancient Libraries - Preserving the Knowledge of Mankind

For centuries, mighty libraries stood as vibrant centres of learning, far more than mere storage for scrolls. These institutions attracted the keenest minds of their eras, diligently collecting and safeguarding humanity's intellectual treasures. In a world without mass communication, these institutions were nothing less than the brain trust of civilizations, shaping thought and advancing discovery. This journey through six of antiquity's greatest libraries reveals their unique contributions, challenges common myths, and celebrates the tireless efforts that kept knowledge alive.

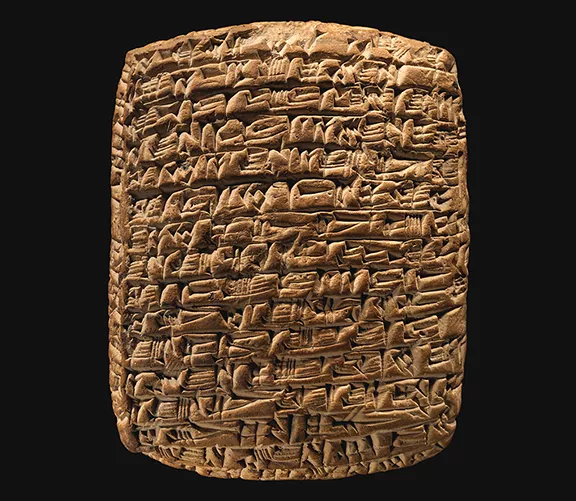

We begin with Ashurbanipal's Library in 7th-century BC Nineveh, a monument to a king's personal passion for scholarship. With over 30,000 clay tablets detailing everything from historical records to the Epic of Gilgamesh, this systematically organized collection served the king and his court. Its dramatic "destruction" by fire in 612 BC ironically hardened the clay, preserving its contents for millennia.

Next, the legendary Library of Alexandria, established in the 3rd century BC, emerged as the ancient world's intellectual powerhouse. Housing hundreds of thousands of scrolls, it drew luminaries like Eratosthenes. Its demise wasn't a sudden inferno, but a centuries-long decline, a gradual dimming rather than an abrupt end.

The Library of Pergamum, Alexandria's 3rd-century BC rival, reportedly held 200,000 scrolls. When an Egyptian papyrus embargo threatened, the Pergamenes innovated, perfecting "parchment" – a durable writing surface that revolutionized bookmaking. Mark Antony's gift of its entire collection to Cleopatra around 43 BC ended its prominence, though not through direct destruction.

In 2nd-century AD Ephesus, the beautiful Library of Celsus, a grand tomb holding an estimated 12,000 scrolls, served the city's educated elite, students, and philosophers. Its ornate facade stands today; a poignant reminder of knowledge intertwined with memory before an earthquake and fire destroyed its interior.

The Imperial Library of Constantinople, founded in the 4th century AD, emerged as the Eastern Roman Empire's intellectual heart. With over 100,000 volumes at its peak, it played a crucial role in safeguarding classical learning. Through dedicated scribes meticulously copying fragile papyrus texts onto durable parchment, this library survived centuries of fires (like the one in 473 AD that consumed 120,000 volumes) until the devastating Sack of Constantinople in 1204 AD and the city's final fall in 1453 AD. It functioned as an intellectual bridge, carrying ancient wisdom towards the Renaissance.

Finally, the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, established in the early 9th century AD, shone as a global hub of learning. Far more than a library, this research academy and translation centre welcomed scholars of all backgrounds. With over 400,000 books, it propelled advancements in mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, attracting minds like al-Khwarizmi and Hunayn ibn Ishaq. Its catastrophic destruction during the Mongol siege of Baghdad in 1258 AD symbolized immense loss, though fortunate prior transfers and the wide dissemination of knowledge across other Islamic centres like Basra, Kufa, and Damascus ensured not all was lost.

These ancient libraries, despite their varied fates, collectively represent humanity's persistent and often heroic effort to preserve, expand, and transmit knowledge across generations. They represent our drive to understand the world and ourselves.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Library of Ashurbanipal: Clay Tablets and Cuneiform Wisdom

Artists impression of the Library of Ashburnipal

King Ashurbanipal, who reigned from 668 to 627 BC, assembled what many consider the first systematically organized library in the ancient Middle East. Located in his palace at Nineveh (Mosul, modern-day Iraq), this astounding collection comprised over 30,000 clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform script. Scribes meticulously copied and catalogued texts, ranging from historical records and legal documents to omens, incantations, and epic poetry.

A King's Passion and Purpose

Ashurbanipal was not just a conqueror; he was a dedicated scholar. He understood the immense power of knowledge for governing his vast empire and for connecting with the divine. His father, Esarhaddon, had ensured he received a thorough education, which was unusual for a prince destined for the throne. Ashurbanipal's personal letters reveal his direct involvement in acquiring texts, dispatching scribes throughout his empire to find and copy every important work. He even kept tablets from his own student days, a touching detail that speaks to his genuine love for learning.

Size and Scope of the Collection

The collection was incredibly diverse, reflecting the broad range of Mesopotamian knowledge:

Divination and Omens: A significant portion of the library was dedicated to texts that helped interpret the will of the gods and predict the future. This was crucial for royal decision-making.

Religious Texts: Hymns, prayers, incantations, and rituals were abundant.

Lexical Texts: Dictionaries and word lists were essential for scribal training and understanding ancient languages like Sumerian, which was no longer spoken but preserved in scholarly and religious contexts.

Literary Works: This included epic poems and myths, most famously the complete Epic of Gilgamesh, alongside other narratives like the Enuma Elis (Babylonian creation myth).

Historical Records: Royal annals detailing military campaigns, diplomatic correspondence, and administrative documents provided crucial insights into the running of the empire.

Scientific and Technical Texts: Astronomy, mathematics, and medical treatises were also present, preserving the advanced knowledge of the time for posterity.

Unlike later libraries, its primary users were the king, his royal scribes, scholars, and diviners, employing the vast knowledge for governance, divination, and scholarship.

The Library's Ultimate Fate – A Fortunate Calamity

The Library of Ashurbanipal met its "destruction" in 612 BC when a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, and Scythians sacked Nineveh, bringing an end to the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Ironically, this catastrophic event was the very reason the library's contents were so remarkably preserved.

As the palace burned, the intense heat of the inferno baked the unfired clay tablets, transforming them into a durable ceramic. This process, akin to firing pottery, hardened them and made them far less susceptible to degradation than if they had remained unfired. When the walls of the palace collapsed, they buried the tablets, protecting them from further damage and the ravages of time. For over two millennia, they lay buried beneath the ruins of Nineveh until their excavation in the mid-19th century by archaeologists like Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam.

The Library of Alexandria: A Myth Reconsidered

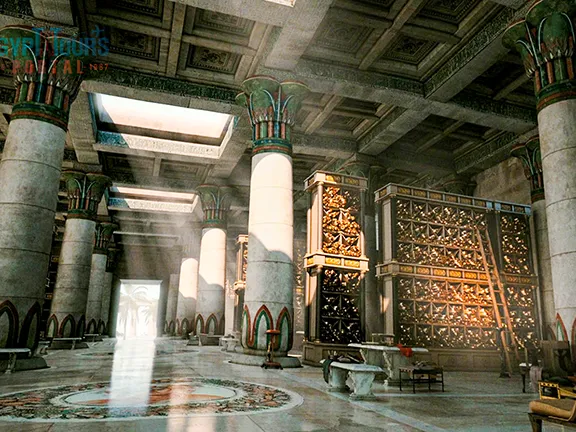

Artists impression of the Library of Alexandria

Founded in the 3rd century BC by Ptolemy I Soter, the Library of Alexandria was the crown jewel of the ancient world. While popular imagination pictures a single, colossal building, the Great Library likely comprised several structures within the Mouseion, a research institute dedicated to the Muses.

Notable Scholars

Scholars like Callimachus, Apollonius of Rhodes, and Eratosthenes studied and worked there, drawing on a collection estimated to have reached hundreds of thousands of scrolls.

Acquiring the Collection

These weren't just original works; the Ptolemies famously funded an ambitious project to acquire copies of every known text, even resorting to "borrowing" and copying books from ships docking in Alexandria.

The Gradual Demise of the Library

Its ultimate demise isn't the clear-cut tragedy often portrayed. Rather than a single catastrophic fire, the library likely suffered a series of declines and damages over centuries, beginning with Julius Caesar's siege in 48 BC and continuing through later conflicts and the rise of Christianity. The final blow wasn't a sudden inferno but a gradual dimming of its intellectual light.

The Library of Pergamum: Built to Rival Alexandria

Ruins of the Library of Pergamum

The Library of Pergamum, established in the 3rd century BC by the Attalid dynasty, was Alexandria’s chief competitor. Located in modern-day Turkey, it reportedly housed around 200,000 scrolls.

The Acropolis of Pergamum (also spelled Pergamon) was the fortified upper city and administrative, religious, and cultural heart of the ancient Greek city of Pergamum, located in modern-day Turkey. Perched dramatically atop a high, steep-sided hill, it offered strategic defensive advantages and commanding views of the surrounding plains.

More than just a fortress, the Acropolis of Pergamum was meticulously planned and developed, particularly during the Hellenistic period under the Attalid dynasty (3rd-2nd centuries BC). It was designed to showcase the power, wealth, and intellectual prowess of the Pergamene kings, who sought to create a city that rivalled even Athens.

The library, a grand hall within the Acropolis of Pergamum, featured a 3.5-metre statue of Athena.

Parchment: Invented in Desperation

What truly sets Pergamum apart is its contribution to the very medium of writing. When Ptolemy V Epiphanes of Egypt, in a fit of jealousy, embargoed the export of papyrus to Pergamum, the Pergamenes innovated. They perfected the use of treated animal skins, giving us "parchment," a more durable and flexible writing surface than papyrus. This material would revolutionize book production and preservation for over a thousand years.

Looted by Mark Antony

Mark Antony, around 43 BC, famously gifted its entire collection to Cleopatra, moving it to Alexandria—an ironic twist in the rivalry of these two intellectual powerhouses.

Some accounts suggest it was a grand wedding present to his new wife, Cleopatra.

Another popular theory is that Antony intended to replenish the Library of Alexandria's collection, which had reportedly suffered damage during Julius Caesar's siege in 48 BC.

The library building, now empty of all its scrolls, suffered damage by earthquakes and the general ravages of time until even its precise location near the Temple of Athena was lost.

The Library of Celsus: A Monument to Knowledge and Memory

Ruins of the Library of Celsus at Ephesus

The Library of Celsus in Ephesus was built as a monumental tomb for Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, a former Roman senator and governor of Asia. While it served as a stunning memorial, it also functioned as a public library for the city of Ephesus.

Built by Gaius Julius Aquila for his father, Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, a former governor of Asia Minor, the library’s ornate facade still stands today in modern-day Turkey.

The niches within its walls once held an estimated 12,000 scrolls. While not a massive collection compared to Alexandria, it was accessible to the educated elite of Ephesus, students and philosophers, and visiting dignitaries.

Uniquely, Celsus's sarcophagus lies beneath the central apse, directly below the statue of Athena, the goddess of wisdom. This deliberate placement highlights the personal connection between the library and the man it commemorated, intertwining knowledge with the afterlife.

The library was destroyed by an earthquake and fire in the 3rd century AD, leaving only its magnificent façade.

The Imperial Library of Constantinople: Preserving Classical Heritage

The Imperial Library of Constantinople - Artists impression

It’s the 4th century AD. The Roman Empire is crumbling, but in the East, a new city offers hope for civilisation, Constantinople. While Rome withered, this vibrant new intellectual hub, born from Emperor Constantine the Great's vision, carefully nurtured and protected the wisdom of the classical world for almost a thousand years.

Preserving Already Ancient Texts

Emperor Constantius II, who ruled from 337 to 361 AD, spearheaded the library's official establishment. He recognized the urgent need to combat the decay of ancient texts, many written on fragile papyrus. He initiated a monumental project: a dedicated scriptorium where skilled scribes meticulously transferred valuable works from brittle papyrus scrolls onto the more durable and versatile medium of parchment. This painstaking effort ensured the survival of countless Greek and Latin literary, philosophical, scientific, and historical masterpieces that otherwise might have vanished forever.

Emperor Valens, later in 372 AD, further solidified this commitment by employing a team of both Greek and Latin scribes, reflecting the bilingual nature of the collection.

At its zenith, the library's collection reportedly soared to over 100,000 volumes, a staggering number for the ancient and early medieval world.

Masterpieces of the Scribal Art

Beyond the sheer volume of their collections, these ancient libraries housed true masterpieces of craftsmanship. Scribes, far from mere copyists, were often skilled artists who meticulously prepared and adorned the written word.

Whether working with the delicate fibres of papyrus or the smooth surface of vellum, they carefully measured and ruled their columns, ensuring uniformity and aesthetic balance. They sometimes employed vibrant inks derived from minerals and plants, or even shimmering gold and silver, to illuminate initial letters, emphasize titles, or create intricate illustrations. This meticulous attention to detail transformed each scroll or codex into a work of art, a beautiful example of the reverence ancient cultures held for knowledge itself, often reflecting the wealth and prestige of the institutions that commissioned them.

Who Used This Vast Collection?

The Imperial Library served as the intellectual heart for the Byzantine court, scholars, and educated elite. Emperors themselves often pursued intellectual interests, and the library offered them direct access to the accumulated wisdom of the past.

Prominent figures like the Byzantine princess Anna Comnena, a renowned historian of the 11th and 12th centuries, undoubtedly drew upon its vast resources for her groundbreaking work, The Alexiad.

While not a public library in the modern sense, its existence fostered a highly literate society by medieval standards. Scholars and theologians relied on its texts for study, debate, and the advancement of learning within the empire.

A Thousand Years of Resilience, A Gradual Demise:

Unlike the dramatic, single-event destruction often associated with Alexandria, the Imperial Library of Constantinople survived centuries of threats. It faced multiple devastating fires, including a significant one in 473 AD that reportedly consumed 120,000 volumes. Yet, each time, the Byzantines demonstrated their unwavering commitment to learning by rebuilding and re-copying lost texts.

The most catastrophic blow, however, arrived not from natural disaster but from human conflict.

The Sack of Constantinople 1204 AD: The brutal Sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Western European Crusaders, driven by greed and religious zeal, plundered and destroyed much of the city, including its invaluable cultural treasures. While some texts may have found their way to the West following this event, a vast portion of the library's holdings vanished.

The Fall of Constantinople 1453 AD: Despite this immense loss, the library continued to exist, albeit in a diminished capacity, through the later Byzantine period. Its final, tragic end came with the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. While some scattered volumes may have survived and reappeared in later centuries, like the famed Archimedes Palimpsest, the bulk of the Imperial Library, along with centuries of accumulated knowledge, perished with the empire itself.

Carrying the Torch of Knowledge

The Imperial Library of Constantinople played a crucial role in safeguarding classical learning, acting as an intellectual bridge that carried the torch of ancient wisdom into the Renaissance and beyond.

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad: A Global Hub of Learning

House of Wisdom from contemporary relief

Established in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate, likely in the early 9th century AD under Caliph Harun al-Rashid and further developed by his son al-Ma'mun, the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) was a groundbreaking institution. It was far more than a library; it was a research academy, translation centre, and intellectual meeting point that drew scholars from diverse backgrounds and faiths.

The Collection of Works

Its collection rapidly grew through the deliberate acquisition of texts from across the known world, including Greek, Persian, Indian, and Chinese manuscripts. Scholars diligently translated these works into Arabic, particularly in fields like mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy.

Estimates for the size of the collection in the original House of Wisdom in Baghdad vary, but many sources suggest it housed more than 400,000 books. Some accounts even claim closer to a million, though exact figures are difficult to verify from that period.

Regardless of the precise number, it was undoubtedly one of the largest and most comprehensive libraries in the world at the time, reflecting the immense intellectual fervour and translation movement of the Islamic Golden Age. The sheer volume of works, encompassing everything from translated Greek, Persian, and Indian texts to original Arabic contributions, made it an unparalleled centre of knowledge.

Who Used the House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom wasn't just a quiet library; it was a bustling intellectual powerhouse that drew scholars from across the vast Abbasid Caliphate that, at its peak, controlled a vast territory stretching across parts of the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa.

The House of Wisdom served as a research academy, a major translation centre, and a forum for some of the greatest minds of the Islamic Golden Age.

Its doors were remarkably open, welcoming individuals of diverse backgrounds, faiths, and ethnicities – Muslim, Christian, Jewish, and even Zoroastrian scholars collaborated within its walls. They were united by a common passion: the relentless pursuit of knowledge.

Caliph al-Ma'mun himself was deeply involved, regularly visiting scholars, inquiring about their research, and even mediating academic debates. He famously encouraged translators by reportedly paying them the weight of each book they translated in gold, emphasizing the immense value placed on acquiring and disseminating knowledge.

Among the many brilliant minds who graced the House of Wisdom's facilities were:

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780-850 AD): A Persian polymath who became a pivotal figure in mathematics. He developed the concept of algebra, deriving its name from his treatise Al-Jabr wa'l-Muqabala. He also played a crucial role in introducing the Indian numeral system (which we now know as Arabic numerals) to the Western world.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809-873 AD): A Nestorian Christian physician and scholar, often called the "Sheikh of the Translators." He was incredibly prolific, translating a vast number of Greek medical and scientific texts, including nearly the entire corpus of Galen and Hippocrates, into Arabic. His meticulous work and the new scientific terminology he introduced vastly enriched the Arabic language.

The Banu Musa Brothers (9th century AD): Three brothers—Muhammad, Ahmad, and Hasan—who were renowned for their work in mechanics and engineering. They authored the Book of Ingenious Devices, detailing over a hundred mechanical inventions, many of which incorporated automata and self-operating machines. They were also patrons of translation themselves, sponsoring the acquisition of many Greek manuscripts.

Al-Kindi (c. 801-873 AD): Often called "the Philosopher of the Arabs," he was a polymath who made significant contributions to philosophy, mathematics, medicine, and astronomy. He pioneered efforts to harmonize Greek philosophy with Islamic thought and was an early innovator in cryptography.

Thabit ibn Qurra (826-901 AD): A Sabian scholar and translator who made substantial contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. He translated major works by figures like Archimedes, Apollonius, and Euclid, and conducted original research in geometry and number theory.

The Mongol Obliteration of Knowledge

The common and widely accepted historical account is that the House of Wisdom, along with most other libraries and intellectual institutions in Baghdad, suffered a catastrophic destruction during the Mongol siege of the city in 1258 AD.

Survivors and later historians vividly recount the Mongols throwing countless books into the Tigris River, reportedly turning the river black with ink. This image has become emblematic of the devastating loss of knowledge during that period.

However, while the destruction was immense and certainly marked the end of the House of Wisdom as the grand institution it once was, it's possible that not every single manuscript or piece of knowledge was irrevocably lost. Here's why some nuances exist:

Prior Transfers: There are accounts that some scholars, anticipating the Mongol threat, may have managed to transport a portion of their personal collections or particularly valuable manuscripts to safer locations before the siege. The Persian scholar Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, for instance, is said to have saved around 400,000 manuscripts by moving them to Maragheh, where he later established an observatory and library under Mongol patronage.

Copies Elsewhere: Many of the texts held in the House of Wisdom were not unique. They were copies or translations of works that might have existed in other libraries, private collections, or scholarly centres across the vast Islamic world, stretching from Andalucia to Central Asia. Texts were disseminated to other Islamic centres of learning such as Basra and Kufa in Iraq, Damascus, Nisibis and Edessa in Syria, and Cairo in Egypt. These cities, with their mosques, libraries, observatories, and eventually madrasas (formal religious colleges), formed a dynamic network where scholars travelled, exchanged ideas, and contributed to the incredible intellectual flourishing of the Abbasid era. The Translation Movement had been incredibly active for centuries, meaning knowledge was more widely dispersed than in earlier times.

Oral Traditions and Memory: While books were the primary medium, a considerable amount of knowledge, especially in fields like poetry, history, and religious studies, also resided in the memories of scholars and through oral transmission.

Survival of Scholars: Although many scholars were killed in the siege, some did survive and continued their intellectual pursuits elsewhere, carrying their knowledge with them.

So, while the physical structure of the House of Wisdom was indeed razed and an unimaginable number of books were destroyed, the broader intellectual tradition and a portion of the knowledge it fostered did manage to survive and contribute to later scholarly endeavours, both within the Islamic world and beyond. The event remains a profound tragedy for human history, but it wasn't an absolute, total obliteration of all knowledge.

Why Libraries Matter: Echoes of the Enduring Mind

In an age when existence often seemed precarious, and knowledge relied on the fragile mediums of clay, papyrus, or parchment, why did civilizations pour such immense resources into building and sustaining these vast collections? The answer lies not merely in practicality, but in a profound, perhaps even instinctual, human quest. Ancient scholars, often grappling with the fundamental questions of cosmos and chaos, understood that knowledge was more than a tool; it was the very essence of human progress and self-understanding.

These libraries, whether the royal preserve of Ashurbanipal or the public halls of Alexandria, implicitly acknowledged that ideas held an immortality denied to the flesh. They were sanctuaries where the fleeting thoughts of one generation could take root, flourish, and transcend time, becoming the bedrock for the next. The very act of collecting, translating, and preserving was an assertion against oblivion, a collective endeavour to chart the limits of human experience and push beyond them. In these hallowed halls, minds across centuries conversed, building upon insights, correcting errors, and ultimately, striving for a wisdom that reflected humanity's highest aspirations. They remind us that the pursuit of understanding is not a fleeting ambition, but a timeless, unifying thread woven through the entire human story.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard A Bronze Age Courier Service

A Bronze Age Courier Service Cyrene's Lost Treasures

Cyrene's Lost Treasures The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy The World's First Company

The World's First Company The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht

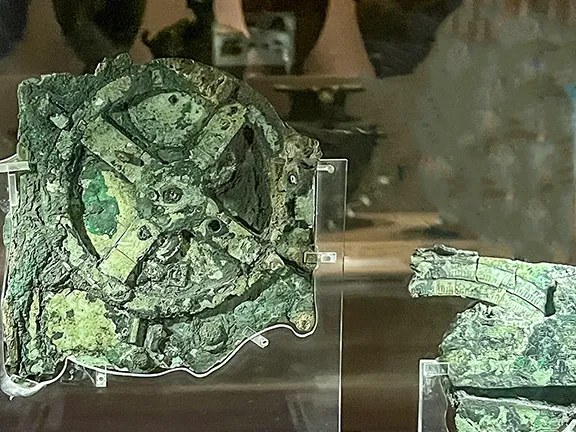

The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht How the Antikythera Mechanism Works

How the Antikythera Mechanism Works Kach Kouch and Iberia

Kach Kouch and Iberia Mediterranean Diet Evolution

Mediterranean Diet Evolution Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues

Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh

Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh Alexandria Library's True Fate

Alexandria Library's True Fate Ancient Greek Technology

Ancient Greek Technology Broadening Horizons

Broadening Horizons The Nadītu Investors of Sippar

The Nadītu Investors of Sippar New light on Hadrian

New light on Hadrian The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba

The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region

New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula

La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion

New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass

Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan

Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain

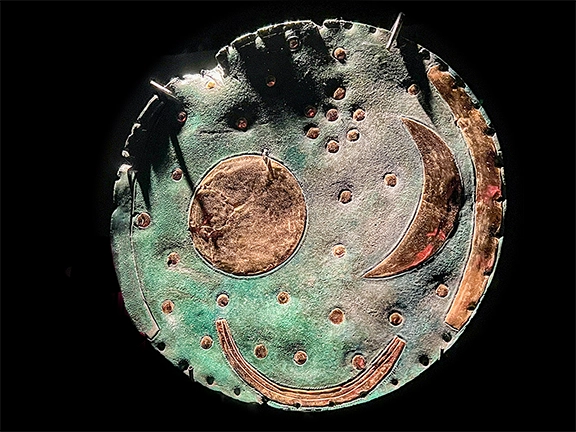

Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar

The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante

New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery

Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt