Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

The First Female Investment Bank: The Nadītu Investors of Sippar

Discover the Nadītu of Sippar, the cloistered capitalists of the Bronze Age. These women controlled vast fortunes, invented limited partnerships, and financed global trade while living in the Gagûm temple complex.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-12-28 | Last Updated 2025-12-29 | Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

This article has been visited 800 times

Imaginary Harem Scene

The First Female Investment Bank: The Nadītu Investors of Sippar

While Babylonian men were sailing off to Dilmun or fighting in their unification wars, a silent revolution in economic history was occurring in the low-lying alluvial plains of Babylonia along the Euphrates, some 30 kilometres south of Baghdad, in what is now Southern Iraq. It was Sippar, and here, contrary to much of what has been learned from ancient cultures, kings and male merchants did not lead the funding of this economy, but a closed order of women known as "Nadītu".

This group of women constitutes one of the oldest recorded incidences of economic independence among women in history. They managed vast amounts of wealth, including purchasing and selling real estate, and perhaps even financing the sea trade with Dilmun.

“Sippar” was a common reference to a two-city complex that was divided by a canal or a river branch.

Sippar proper (Sippar-Yaḫrurum): The principal city was located near the present-day Tell Abu Habbah, the site of the famous Ebabbar temple of the Sun God Shamash. The heart of this finance power was the Gagûm (meaning “The Locked Place” or Cloister). It was a walled residential area with the Ebabbar Temple, where resided the Sun God and Lord of Justice, Shamash.

Sippar-Amnanum: Its sister city (or suburb), was a short 6 km to the northeast from the current Tell ed-Der. It had a different patron deity: the goddess Annunitum (who was a warlike form of the goddess Ishtar).

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Gagûm of Sippar

The Gagûm of Sippar maintained a large number of women within its convent. However, these were hardly nuns in the modern conception of the term—poor, silent, and chaste. They were the choicest daughters of the richest families in Babylon.

They resided in private houses within the walls with servants or slaves. They were permitted to own properties, carry out business transactions, and move out of the convent during the daytime, and had to return at night.

The Brides of Shamash

In order to become a Nadītu, the woman was "married" to the god Shamash. Being a Nadītu included strict social norms, which paradoxically granted her economic freedom.

Celibacy (Mostly): The Nadītu of Shamash could not marry or have offspring in most cases.

The Dowry Loophole: In the case of the law of the land, the husband would generally take the dowry of the married woman. Now, that wasn’t the case with the Nadītu, who did not have any husband.

The Nadītu

Ring Money: The Nadītu often wore their riches on their persons. The Archives tell how Nadītu women received their bridal gift in the form of “silver rings”, which consisted of har-ku-babbar, or large wrist coils resembling Bracelets of Value that functioned as both heavy jewellery and portable bullion.

The Tappūtum - Inventing the Limited Partnership

Since the Nadītu were banned from going long distances, they required means to benefit from the silver. They utilised a type of lawful contract known as the Tappūtum or (Partnership).

Such was the equivalent of the Venture Capital agreement in the Bronze Age. The Nadītu were the ‘Silent Partners’, who contributed the capital, either in the form of gold or silver. A merchant, sometimes the alik Tilmun, the merchant from the land of Dilmun, acted as the ‘Active Partner’.

The terms of the contract normally stated that once the merchant returned, the Nadītu shall receive her original investment as well as 50% of the net profit. The remaining 50% profit went to the merchant as his commission.

These were not loans with guaranteed interest; rather, they were equity investments. If the boat sank or the pirates stole the cargo, the Nadītu might lose her money, unless she included a special clause requiring the merchant to assume the risk, known as "making the merchant an enemy of the city."

Real Estate Moguls

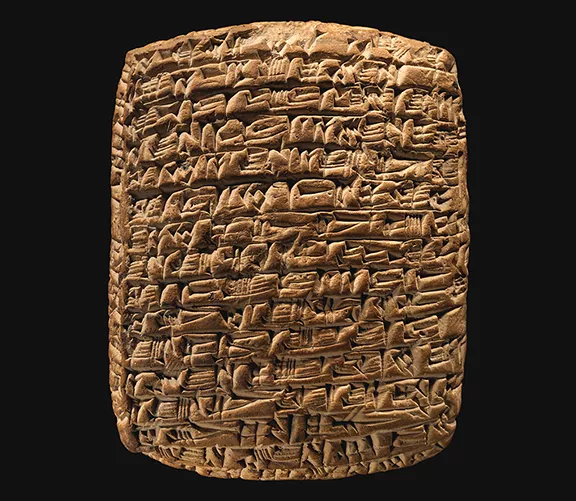

Even as they invested in trade, the Sippar archives, which contain thousands of documents, suggest that their real love was Real Estate.

The Nadītu were aggressive landlords. The Nadītu bought agricultural fields, orchards, and city property lots. The Nadītu rented land to tenant farmers, charging barley and sesame as rents.

They usually practiced “harvest arbitrage.” They lent silver to desperate farmers during the winter and collected the money back with interest in the form of barley during the harvest season, thus buying grain at rock-bottom prices for resale later when the price rose.

The Problem with Aunts

The Nadītu system worked as a convenient mechanism for the upper classes to maintain their property: by marrying his daughter to a Gagûm, a man could guarantee that she would have no offspring to assert a claim to family land. After she died, property would automatically pass to her brothers or their sons.

Yet the records are chock-full of instances in which Nadītu wives challenged the system.

Adoption: In a bid to circumvent the rights of her brothers, an older Nadītu woman would "adopt" her younger niece (or a slave girl) and choose her as her heir.

Cases brought by Nadītu women against their brothers for stealing their portion of the paternal inheritance exist. They hired the most skilled scribes due to their literacy and wealth; therefore, many of them won.

The Rise and Fall of the Investors of Sippar

The 'Investors of Sippar' were a strong economic power for about 300 years, overlapping the Old Babylonian Period. The 'Golden Age' of their control of finances lasted approximately from 1880 BC to 1550 BC.

The Rise (c. 1880 - 1792 BC)

The Gagûm emerges as a functional institution during the early periods of the First Dynasty of Babylon.

When the Amorite dynasties, such as the reign of Sumu-abum, established power in Sumer and Akkad, the era of big business ensued. Indeed, Nadītu women were reportedly buying fields and engaging in local financing well before the reign of Hammurabi, under the reigns of such early kings as Sin-muballit.

The Peak (circa 1792 – 1750 BC)

The institution reached its peak during the reign of King Hammurabi.

His sister, Iltani, was the Nadītu at Sippar. This gave the cloister incredible status and wealth because it was, in effect, a royal affiliation. The renowned Hammurabi Code contains at least 20 separate laws that protected the rights, dower, and succession rights of the Nadītus, thereby making them a protected class with regards to finance.

Despite the above characteristics of the time, this era was not without challenges which would later contribute to the downfall of the Nadītu system. This era of the Old Babylonian kingdoms, particularly the reign of Hammurabi, has been described as one characterised by “total war” in the south. The state maintained a feudal obligation known as ilkum. Many members of the “middle class” were rēdûm (soldiers/musketeers) or bāirum (scouts/fishermen).

“The flat alluvial plains” were an arena for the conflict of the city-states. The men of the cities of Babylon and Sippar were at war on all fronts against numerous enemies.

Larsa was the great rival power to the south (ruled by King Rim-Sin I). They controlled the harbour of Ur and the lucrative Gulf trade during much of this period. A bitter contest for dominance between Babylon and Larsa continued for decades until Hammurabi finally broke the power of Larsa in 1763 BC.

Elam was the highland civilisation from Iran. The Elamites invaded the lowland regions quite often and were the “suzerain” power which always attempted to maintain a divided Mesopotamia.

Eshnunna was a potent trading state in the east, in the area around Diyala, always threatening the side of Babylon.

Lastly, there is Mari in the north. Although this was another alliance, Babylon ended up attacking Mari in order to ensure the rights to the waters of the Euphrates River.

The Decline (ca. 1720 – 1595 BC

The system gradually fell into disuse in the late Old Babylonian period (during the reign of kings such as Samsu-iluna and Ammi-saduqa).

Southern Babylonia experienced ecological and economic collapse, with consequent rebellion and de-urbanisation. With the shrinkage of the economy, the high-risk, high-reward activities of the Nadītu became less feasible.

The institution fades from the pages of history after the Sack of Babylon in 1595 BC, by the Hittites. During the reign of the succeeding Kassite Dynasty, the social organisation underwent changes. While the temple of Shamash continued to exist, the strong and relatively autonomous “female investment bank” called the Gagûm ceased to be seen in history.

References

Crawford, H. (1998). Dilmun and its Gulf Neighbours. (Cambridge University Press).

Harris, R. (1975). Ancient Sippar: A Demographic Study of an Old-Babylonian City (1894-1595 B.C.).

Michel, C. (2020). Women of Assur and Kanesh: Texts from the Archives of Assyrian Merchants.

Stol, M. (2016). Women in the Ancient Near East. De Gruyter. Stone, E. C. (1982). "The Social Role of the Nadītu Women in Old Babylonian Nippur." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 25(1). Veenhof, Klaas & Eidem, Jesper. (2008). Mesopotamia: The Old Assyrian Period.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard A Bronze Age Courier Service

A Bronze Age Courier Service Cyrene's Lost Treasures

Cyrene's Lost Treasures The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy The World's First Company

The World's First Company The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht

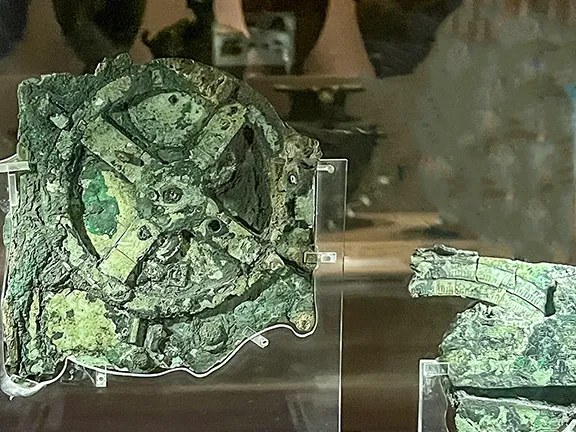

The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht How the Antikythera Mechanism Works

How the Antikythera Mechanism Works Kach Kouch and Iberia

Kach Kouch and Iberia Mediterranean Diet Evolution

Mediterranean Diet Evolution Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues

Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh

Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh Alexandria Library's True Fate

Alexandria Library's True Fate Six Great Ancient Libraries

Six Great Ancient Libraries Ancient Greek Technology

Ancient Greek Technology Broadening Horizons

Broadening Horizons New light on Hadrian

New light on Hadrian The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba

The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region

New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula

La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion

New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass

Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan

Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain

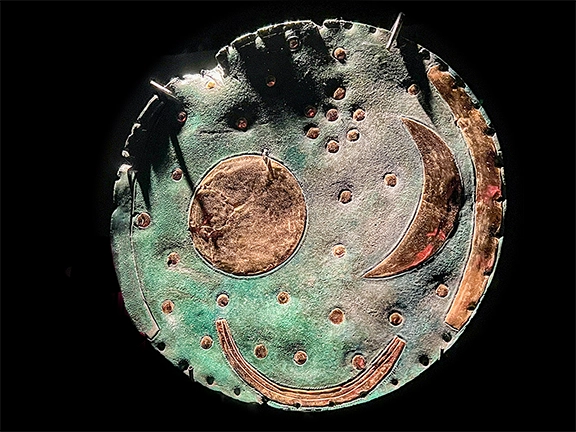

Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar

The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante

New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery

Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt