Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

The world's first courier service in the bronze age Middle East

The world's first courier service was developed during the bronze age in the Middle East between 2400 and 1200 BC. The network connected all the major, and minor, civilisations, city states and societies of the day.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-02-9 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

This article has been visited 5,451 times

Let's Hear it for the Bronze Age Couriers

Greetings, history buffs and communication enthusiasts alike! Today, we delve into the fascinating world of the Bronze Age, not through the lens of warfare or monuments, but through the unsung heroes of the era: the couriers. That's right, folks, we're talking about the ancient postal service, a sophisticated network that predates even the UK Postal Service's recent, shall we say, "challenges."

Our story paints a vivid picture of a world interconnected long before the internet or even the printing press. We will be discovering little known pharaohs and extinct forms of writing. Buckle up, because we're about to embark on a journey through time, tracing the evolution of this ancient courier system.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Egypt c 2400 BC

An Egyptian Messenger

Our story begins with Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi, a name you might not be familiar with, but a ruler who deserves recognition for revolutionizing communication around 2400 BC. This visionary pharaoh established the world's first known courier system, stretching across the vast Egyptian kingdom. Imagine runners relaying papyrus scrolls inscribed with the pharaoh's words of wisdom, or rather hieroglyphs, carrying news and orders across 2,500 kilometres. Talk about dedication.

King Sargon of Akkad

Sargon the Great with tablet

Egypt wasn't the only player in the communication game. In southern Mesopotamia, King Sargon of Akkad, justifiably known as Sargon the Great, and his successors were building a new type of hierarchical bureaucracy and centralized government from about 2334 BC. Over 150 letters written in a cuneiform script called Akkadian, have been recovered from this period. Most of the letters are between 10 and 25 lines long, and concern personal matters, legal affairs, real estate matters and economic concerns.

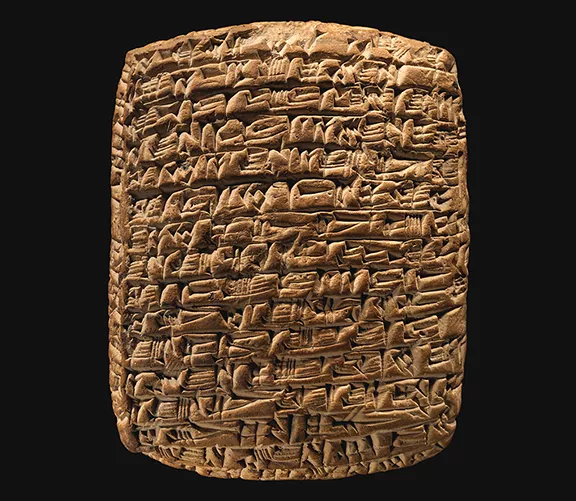

Cuneiform Script

Cunieform script

At that time, Mesopotamia did not have access to papyrus and the cuneiform written form, composed using wedge shaped characters, was better suited to a soft clay surface.

Cuneiform is not a language but a proper way of writing distinct from the alphabet. It doesn't have 'letters' , instead it uses between 600 and 1,000 characters impressed on clay to spell words by dividing them up into syllables, like 'ca-at' for cat, or 'mu-zi-um' for museum.

Cuneiform script was used to write multiple languages including Akkadian, Sumerian, Eblaite, Hurrian, Elamite, and Hittite.

Merchant Traders and Oligarchs

Kings and pharaohs were not the only people to see the benefits of rapid communication. By 2000 BC, merchants and traders were getting in on the act. During the first three centuries of the 2nd millennium BC, Assur, an Assyrian city located on a plateau above the Tigris River in Mesopotamia, was an independent city-state dominated by an oligarchy of merchants. At the end of the 20th and beginning of the 19th century BC, the Assyrian merchants had developed long-range trade to central Anatolia, settled there and organized trading outposts, most prominent of which was Kanesh, now called Kultepe in Turkey. Most of the 22,500 Assyrian tablets were found in the houses of merchants located in the lower town; they belong to the private archives, mainly of Assyrian merchants, and contain letters, legal texts and private notices.

Invention of the Envelope

Tablet with envelope

The clay tablets were covered by clay envelopes inscribed with the identity of the correspondents as well as the seal impression of the sender. Tablets in their envelopes were wrapped in textiles and leather and carried on donkey caravans or by special messenger.

The Mari Tablets

Still in Mesopotamia, around 1800 BC, the Mari tablets were written, offering a glimpse into the royal correspondence of the time. Among the principal figures mentioned is the celebrated lawgiver Hammurabi of Babylon also the king of Aleppo, part of whose kingdom was the city of Alalakh, on the Orontes near what was later Antioch. The Mari tablets weren't your average love letters, mind you. They were clay tablets that could measure 25 x 20 centimetres and were a couple of centimetres thick, covered with Akkadian script, carried by couriers who, unlike their Egyptian counterparts, likely used chariots for these hefty messages.

The Mari letters are just a few of the more than five thousand Old Babylonian letters that have been recovered that were sent between rulers, officials, and private individuals.

Hammurabi incidentally laid down the law "An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth", that, over a thousand years later, made it into the book of Leviticus in the Bible. He also came up with, "If anyone bites off the nose of a free person, he shall pay 40 shekels of silver". I do wonder how many times that fine was imposed.

Chariot or Horse?

Horses weren't yet the trusty steeds of these couriers. The debate rages on whether they were ridden at this point, but chariots were definitely in the picture, offering some relief from the weight of those clay tablets. As technology progressed, horses did eventually enter the scene, giving the couriers a well-deserved leg (or hoof) up!

It must have been a fine sight. A light chariot, flying the flag of the king, pulled by four horses, hurtling down the road at 60 kilometres per hour, escorted by cavalry armed with sword and shield, the whole cavalcade raising a cloud of dust that could be seen for miles. Each of these unsung heroes vied to cover the route in record time. One wonders at the tall tales told in the post houses. It is little wonder that, over a thousand years later, they inspired the Greeks to include chariot racing in the first Olympics and the Romans to build hippodromes in which to stage chariot races.

Letters in the Civilised World

Egyptian papyrus scroll

Fast forward to the Armana letters, written between 1360 and 1332 BC. The "civilized world" had expanded, encompassing Mycenaean Greece, Hatti, the Kassite kingdom of Babylon, Assyria, and Mitanni, an area that today covers Greece including Crete, Cyprus, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, part of Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Gaza, Sinai, and Egypt. And guess what? They all had their own versions of the courier system, now interconnected.

Imagine the information flowing across continents, carried by dedicated individuals who braved scorching deserts and treacherous terrain. These networks carried more than just messages; they were arteries of information, culture, and trade. The Armana archive is a treasure trove of letters exchanged between rulers, offering a glimpse into this vibrant interconnected world.

Over 380 letters have been found that were carried between the rulers of the city states that made up the kingdoms, and the two pharaohs in Egypt that ruled during this period, Amenhotep III (1388 to 1351 BC) and Amenhotep IV (1351 to 1334 BC).

Diplomatic Immunity

Back in those days, there was no real concept of diplomatic immunity, and the various rulers were paranoid that they were allowing spies into their midst. Couriers, and their armed escorts, could be held by the recipients of the letters at the king's, or pharaoh's, pleasure. Indeed, some couriers were imprisoned for years before being allowed to return to their homeland, some even died in captivity. So, in addition to bandits and robbers enroute, the couriers had to contend with being kidnapped when they reached their destination. Not an easy life.

Collapse of a World System

Sadly, between 1300-1100 BC, the great Bronze Age civilizations collapsed, taking this intricate communication network with them. It wouldn't be until centuries later, in the 5th century BC, that a similar system would rise again under the Persian Empire.

So, the next time you send a message or receive a package, remember the unsung heroes of the past. The Bronze Age couriers, with their papyrus scrolls, chariots, clay tablets, and unwavering dedication, laid the groundwork for the interconnected world we live in today. They may not have had smartphones or email, but their ingenuity and perseverance deserve a standing ovation.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard Cyrene's Lost Treasures

Cyrene's Lost Treasures The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy The World's First Company

The World's First Company The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht

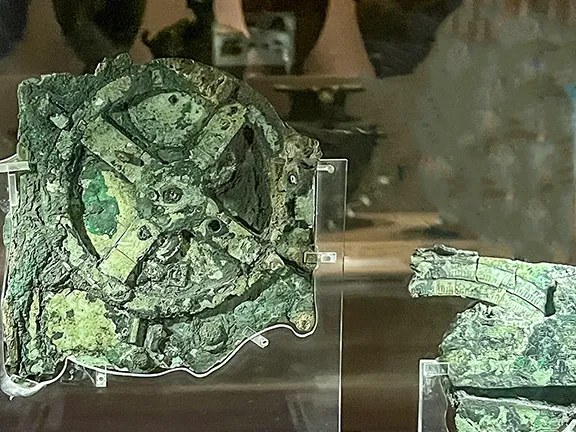

The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht How the Antikythera Mechanism Works

How the Antikythera Mechanism Works Kach Kouch and Iberia

Kach Kouch and Iberia Mediterranean Diet Evolution

Mediterranean Diet Evolution Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues

Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh

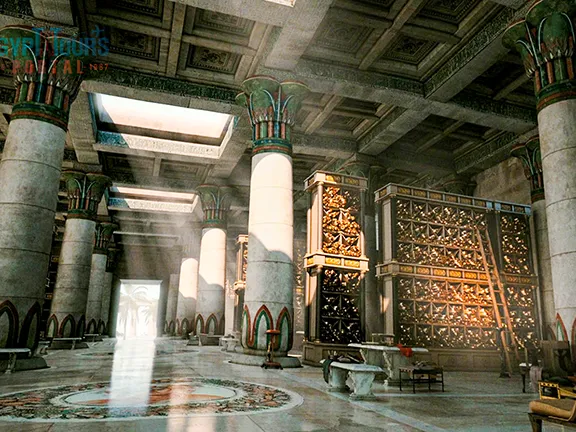

Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh Alexandria Library's True Fate

Alexandria Library's True Fate Six Great Ancient Libraries

Six Great Ancient Libraries Ancient Greek Technology

Ancient Greek Technology Broadening Horizons

Broadening Horizons The Nadītu Investors of Sippar

The Nadītu Investors of Sippar New light on Hadrian

New light on Hadrian The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba

The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region

New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula

La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion

New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass

Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan

Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain

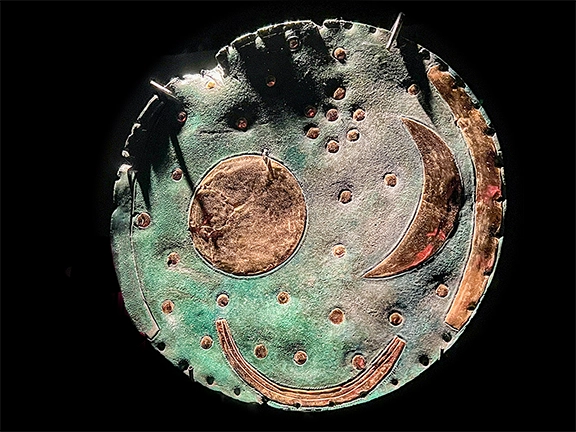

Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar

The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante

New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery

Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt