Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

A Culinary Odyssey: Tracing the Evolution of the Mediterranean Diet

Discover the fascinating journey of the Mediterranean diet. From ancient grains and olives to the impact of the Columbian Exchange, explore how diverse foods shaped this healthy culinary tradition.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-1 | Last Updated 2025-07-2 | Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

This article has been visited 1,852 times

Fresh fish, part of the Mediterranean diet

The Ancient Foundations: The Mediterranean Triad

The Mediterranean diet, celebrated globally for its health benefits and vibrant flavours, is far from a static entity. It's a living culinary tradition, a delicious demonstration of centuries of cultural exchange, agricultural innovation, and adaptation to the diverse landscapes surrounding the Mediterranean Sea.

While its core principles – an abundance of plant-based foods, healthy fats from olive oil, and moderate consumption of fish, meat and dairy – have remained remarkably consistent, the specific ingredients woven into this dietary melange have evolved significantly over time.

At its heart, the earliest iterations of the Mediterranean diet were built upon what archaeologists call the "Mediterranean Triad": wheat, olives, and grapes. These three staples, cultivated for millennia, formed the bedrock of daily sustenance.

Wheat: A Millennia of Sustenance

Domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 10,000 years ago, wheat quickly spread across the Mediterranean basin. It was consumed in various forms, from simple porridges and flatbreads in ancient Greece and Rome to the more refined breads that became central to Roman culture. Wheat-based products like pasta and couscous would later emerge, becoming iconic elements of regional cuisines.

Olives: The Liquid Gold of the Mediterranean

Originating in Persia and Mesopotamia, olive cultivation reached the Mediterranean thousands of years ago. The olive tree thrived in the region's climate, providing not only its distinctive fruit but also the invaluable olive oil, which became the primary source of fat for cooking, dressings, and even as a fuel for lamps. Its pervasive use remains a defining characteristic of the Mediterranean diet.

Grapes: More Than Just Wine

The domestication of grapes and the art of winemaking also predate recorded history in the region. Wine, often diluted with water, was a fundamental part of daily life, offering both hydration and a source of calories. It also held significant cultural and religious importance.

Alongside this foundational triad, ancient Mediterranean diets incorporated indigenous legumes (such as lentils and chickpeas), seasonal vegetables like chicory, leeks, mallow, and fruits. Fish, shellfish and molluscs were eaten in coastal communities. Meat, primarily pork, consumption was generally infrequent, reserved for special occasions or religious festivals, with sheep and goat's milk used for cheeses.

The chicken originated in southeast Asia and arrived in the Mediterranean about 800 BC. Greek and Phoenician traders soon carried this useful bird to all corners of the Mediterranean.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Barbarian and Arab Influx: New Flavours and Techniques

The Arabs introduced new fruit and vegetables

The fall of the Roman Empire and subsequent migrations brought new influences. Visigoth and Goth populations, with their silvopastoral economies, introduced more game meats, and wild-foraged vegetables, enriching the previously more agrarian diet.

The silvopastoral system integrates trees, forage (pasture), and grazing livestock on the same land, aiming for mutual benefit. It's a way to manage land that combines forestry with livestock farming, creating a more sustainable and productive environment. Remarkably, the parkland-like dehesas of Andalucia date back to this period.

From Rice to Citrus: Arab Innovations

However, it was the arrival of the Arabs in the 8th century that truly sparked a culinary revolution in the southern Mediterranean. They not only introduced new agricultural practices but also a diverse array of ingredients and a more sophisticated approach to seasoning. Key additions from this period include:

Rice: A staple in many parts of the world, rice made its way to the Mediterranean through Arab trade routes, becoming particularly important in Spanish paellas and Italian risottos.

Citrus Fruits: Oranges, lemons, and other citrus varieties were brought by the Arabs, adding a refreshing, acidic dimension to dishes and providing vital vitamins.

New Vegetables: Eggplant (of Indian origin), spinach, chard, okra, and cauliflower found their way into Mediterranean kitchens, diversifying the vegetable palate.

Sugar Cane: While not as central as other ingredients, sugar cane was also introduced, paving the way for sweet treats and desserts.

Dried Pasta: While some forms of dough existed earlier, the Arabs are often credited with popularizing dried pasta, particularly in southern Italy, allowing for more durable and transportable food sources.

Aromatic Additions: The Spice Trade's Impact

Spices: From the Far East, the Arabs introduced a wealth of spices like cumin, caraway, aniseed, saffron, and cinnamon, transforming the aromatic profiles of regional cuisines.

Ice for Sherberts

A few of the round, walled ‘ice holes’ that you stumble across in the mountains of Andalucia predate the Muslim occupation, but most were built after 711 AD. Labourers would trek into the mountains with donkeys, cut the ices from the ice holes, wrap it in straw and carry it down to the palaces and homes of rich merchants in Granada, Seville and Cordoba. Many such residences had ice houses dug into the ground to keep the ice from melting. There it was used for cooling drinks and desserts, preserving food and medicinal purposes. One governor of Madinat al-Fath, the ‘City of Victory’, built on Gibraltar during the 12th century AD, even gave instructions to his servants on how to remove straw and manure from the ice before plopping it into his glass of sherbet.

The Columbian Exchange: A World of New Foods

Fresh meat, part of the Mediterranean diet

The voyages of Christopher Columbus in the late 15th century opened up the "New World" and unleashed the most dramatic transformation of global food systems, including the Mediterranean diet. Foods previously unknown in Europe quickly became integrated into local culinary traditions.

The Tomato Revolution: Redefining Mediterranean Cuisine

Tomatoes: Perhaps the most iconic New World import, tomatoes revolutionized Mediterranean cooking, becoming the base for countless sauces, stews, and salads. It's almost impossible to imagine Italian or Spanish cuisine without them today.

Potatoes: While slower to gain widespread acceptance, potatoes eventually became a significant carbohydrate source, particularly in regions where wheat cultivation was less prevalent.

Peppers and Chili: From sweet bell peppers to fiery chilies, these additions brought new flavours, colours, and a spicy kick to Mediterranean dishes.

Corn (Maize): While not as universally adopted as wheat, corn found its place in certain regional diets.

New Legumes: Varieties of beans from the Americas further diversified the already rich legume consumption.

Turkey: This new poultry offered another option for meat, although red meat consumption largely remained moderate.

Modern Adaptations and the Future

In recent centuries, the Mediterranean diet has continued to evolve, albeit with more subtle shifts. Globalization and improved transportation have made a wider array of foods available year-round. However, the core tenets of the traditional Mediterranean diet – an emphasis on fresh, seasonal, unprocessed foods with moderate amounts of poultry, fish and red meats – remain its distinguishing features.

Today, challenges such as the rise of processed foods and Western dietary patterns threaten the traditional Mediterranean way of eating in its homeland. Yet, its lasting recognition as a remarkably healthy and sustainable diet, even being inscribed by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, underscores its historical roots and its remarkable adaptability.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard A Bronze Age Courier Service

A Bronze Age Courier Service Cyrene's Lost Treasures

Cyrene's Lost Treasures The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy The World's First Company

The World's First Company The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht

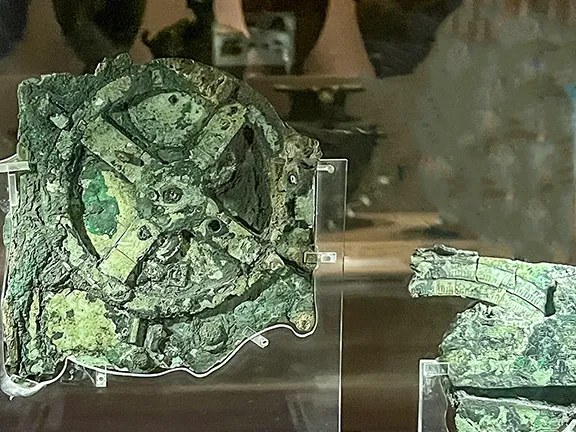

The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht How the Antikythera Mechanism Works

How the Antikythera Mechanism Works Kach Kouch and Iberia

Kach Kouch and Iberia Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues

Hidden Colours of Ancient Statues Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh

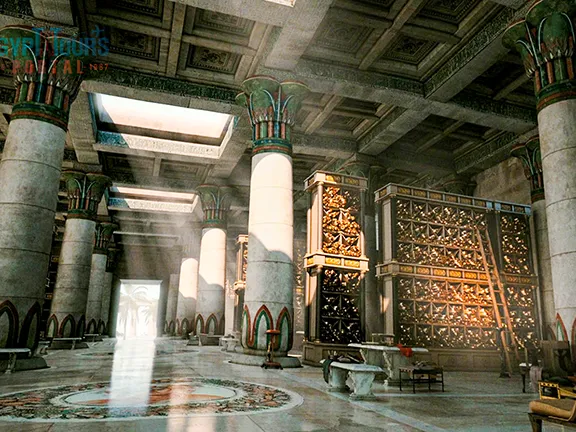

Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh Alexandria Library's True Fate

Alexandria Library's True Fate Six Great Ancient Libraries

Six Great Ancient Libraries Ancient Greek Technology

Ancient Greek Technology Broadening Horizons

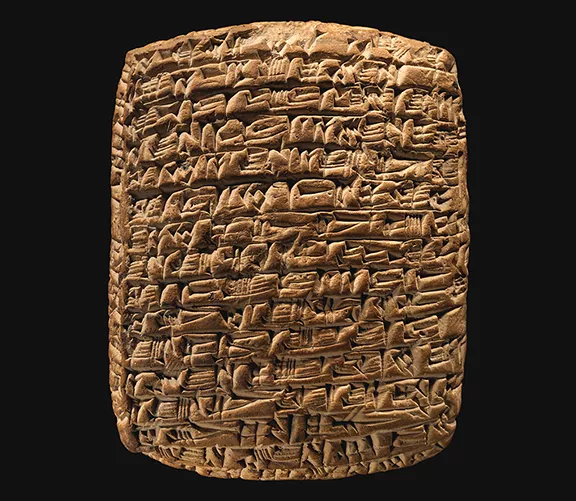

Broadening Horizons The Nadītu Investors of Sippar

The Nadītu Investors of Sippar New light on Hadrian

New light on Hadrian The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba

The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region

New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula

La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion

New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass

Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan

Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain

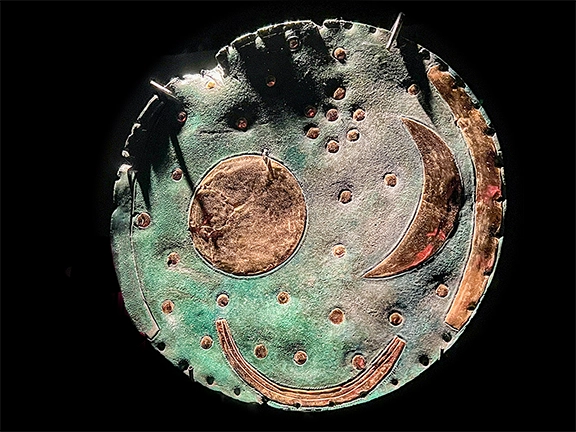

Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar

The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante

New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery

Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt