Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

Beyond White Marble: The Vibrant Truth of Ancient Greek & Roman Statues

Discover the surprising history of ancient Greek and Roman statues – they were vividly painted! Learn about their discovery, preservation by the Persians, and modern efforts to reveal their original polychromy.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-3 | Last Updated 2025-07-3 | Titbits and News from the Mare Nostrum

This article has been visited 2,058 times

Artists impression of the Parthenon as it was in 432 BC - Freebible Images

Beyond the Marble: Unearthing the Vibrant Truth of Ancient Statues

When you picture a classical Greek or Roman statue, what comes to mind? Most likely, it's the pristine, unblemished white marble we see in museums today. But what if I told you that this iconic image is, in fact, a modern misconception? Prepare to have your perceptions shattered, because the ancient world was a riot of colour, and its sculptures were no exception!

For centuries, we’ve admired the stark beauty of unpainted classical statues, leading us to believe that this was their original, intended state. The truth, however, is far more vibrant and, frankly, much more accurate to the aesthetics of the time. Ancient Greek and Roman statues were boldly, beautifully, and often shockingly, painted.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Colours in Ancient Life

Sphynx with original colours - Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Pythagoreans held that the four basic colours of the ancients, black, white, red and ochre, were associated with the four elements of life, water, air, fire and earth, respectively.

Empedocles (c. 494 – c. 434 BC) was a Greek philosopher and poet from Acragas (modern Agrigento, Sicily). He is considered one of the most important of the "Presocratic" philosophers, meaning he lived and worked before Socrates.

He is best known for his cosmogonic theory of the four classical elements: earth, air, fire, and water. He called these "roots" and believed that all matter was composed of different combinations of these elements. To explain how these elements mixed and separated, he introduced two opposing cosmic forces: Love (or Philia), which brings elements together, and Strife (or Neikos), which separates them. He envisioned a cosmic cycle of eternal change, growth, and decay driven by the continuous battle for supremacy between Love and Strife.

Empedocles developed a theory that colours were perceived through the eye via suitable receptors that detected the ‘particles’ that colours emit - a remarkably perceptive theory that was only improved in the early 19th century AD.

Diogenes of Apollonia defined diseases by using the basic colours to divide people into colour categories.

The ancient Greeks also used colour to characterize various attributes. The blonde hair of the gods projected their power, the brown skin of warriors and athletes signified virtue and valour while the white skin of the korai (sculptures of young, draped females), expressed the grace and radiance of youth.

The Persian Fury and a Fortunate Burial

Greek statue partially reformed - Acropolis Museum

So, why did we lose sight of this colourful past? Part of the answer lies in a devastating historical event: the Persian invasion of Greece in 488 BCE. As the Persians sacked Athens, they toppled and buried countless Greek statues, particularly those on the Acropolis. This act of destruction, ironically, became an act of preservation. Buried beneath the earth, these fragmented statues were protected from the elements and, crucially, from the later Roman and Renaissance-era penchant for stripping away polychromy to reveal the "pure" marble beneath.

A Most Fortuitous Discovery: 1885 AD

What restorers have to work with - Acropolis Museum

Fast forward to 1885 AD, and the archaeological excavations on the Athenian Acropolis began to unearth these buried treasures. What emerged from the earth was not the stark white marble we expected, but fragments bearing tantalizing traces of colour. These discoveries sparked a new understanding, challenging the long-held belief in the monochromatic nature of classical sculpture.

The Dawn of Polychromy Research: Pioneering Efforts

Statue of Roman Emperor Augustus similarly refurbished - Vatican Museum

The initial revelation was just the beginning. Early pioneers began the painstaking work of documenting and understanding these faint remnants of paint. L.E. Gillieron and W. Lermann were among the first to meticulously record the surviving pigments, producing valuable early reproductions and analyses that demonstrated the extent of the original coloration. Their work, though limited by the technology of the time, laid the groundwork for future research.

A Modern Renaissance: Bringing Colour Back to Life

Greek archer restored - Original from the Acropolis, Athens

In recent decades, advancements in scientific analysis have revolutionized our understanding of ancient polychromy. Researchers like V. Brinkmann and J. Stubbe Ostergaard have been at the forefront of this modern "colour revolution." Utilizing sophisticated techniques such as UV-Vis spectrometry, X-ray fluorescence, and raking light photography, they can identify microscopic traces of pigment that are invisible to the naked eye.

This innovative work has allowed for incredibly accurate reproductions of what these statues would have looked like in their prime. The results are often startling: goddesses with vibrant red lips and blue eyes, heroes with patterned cloaks, and architectural elements adorned with intricate geometric designs. Imagine the Parthenon not as a gleaming white temple, but as a dazzling spectacle of reds, blues, and golds!

Why Does It Matter?

Understanding the painted nature of ancient statues is more than just a historical curiosity. It fundamentally changes our perception of ancient aesthetics, craftsmanship, and even their worldview. It reminds us that:

Ancient art was not minimalist: It was vibrant, dynamic, and often surprisingly gaudy by modern standards.

Context is key: The colours served not just decorative purposes but also helped to tell stories, differentiate figures, and convey meaning.

Our understanding is constantly evolving: History is not static. New discoveries and technological advancements continue to reshape our knowledge of the past.

So, the next time you encounter a seemingly pristine white marble statue, take a moment to imagine it in its original glory – a vibrant, polychromatic masterpiece, bursting with the colours of the ancient world. The true beauty of these works lies not just in their form, but in the rich, colourful stories they have yet to fully tell.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard

Dana Island, oldest ancient shipyard A Bronze Age Courier Service

A Bronze Age Courier Service Cyrene's Lost Treasures

Cyrene's Lost Treasures The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Enemy The World's First Company

The World's First Company The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht

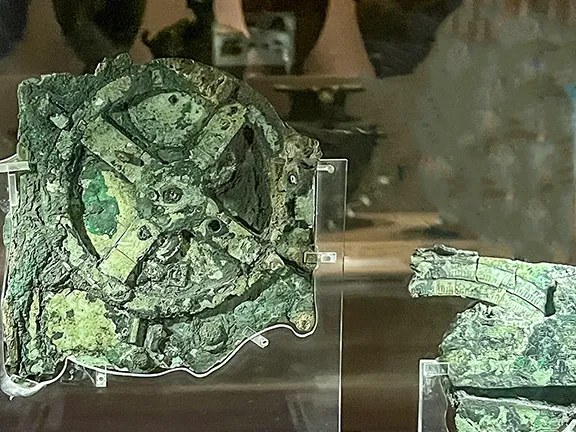

The Copper Age Site of Oued Beht How the Antikythera Mechanism Works

How the Antikythera Mechanism Works Kach Kouch and Iberia

Kach Kouch and Iberia Mediterranean Diet Evolution

Mediterranean Diet Evolution Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh

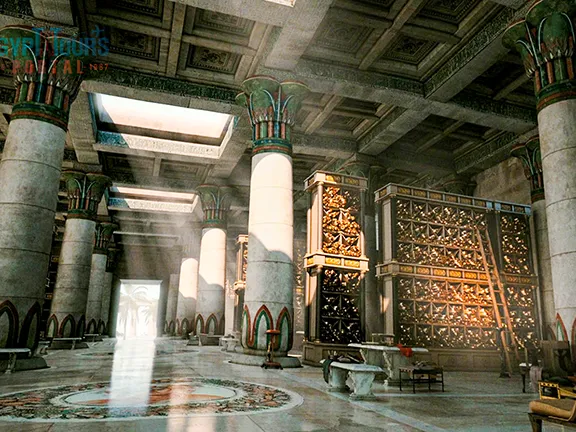

Cleopatra: Egypt's Last Pharaoh Alexandria Library's True Fate

Alexandria Library's True Fate Six Great Ancient Libraries

Six Great Ancient Libraries Ancient Greek Technology

Ancient Greek Technology Broadening Horizons

Broadening Horizons The Nadītu Investors of Sippar

The Nadītu Investors of Sippar New light on Hadrian

New light on Hadrian The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba

The Dolmens of La Lentejuela Teba New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region

New Cave Art Discovery in Valencia region La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula

La Cabaneta Oldest Roman Forum in Iberian Peninsula New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion

New Discoveries at Ancient Sunken City of Thonis-Heracleion Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass

Europe's Oldest Shoes Found: 6,000-Year-Old Sandals Woven from Grass Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan

Discoveries at Gobekli Tepe and Karahan Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain

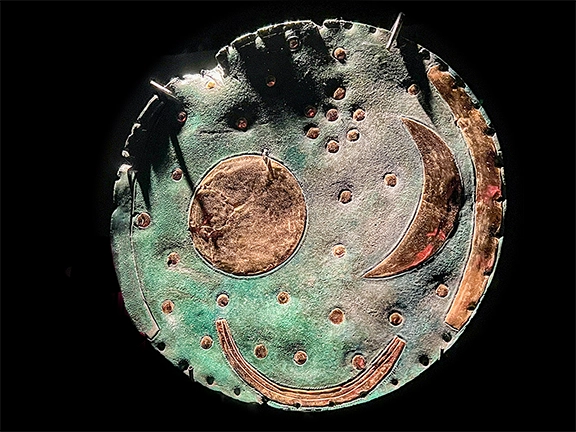

Decorated Stelae found in Canaveral de Leon, Spain The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar

The Nebra Sky Disc: A Bronze Age Calendar New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante

New Exhibition at the Archaeological Museum in Alicante Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery

Bronze Age: A Golden Age for Jewellery The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt