Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The Wenamun Report: Ancient Egypt's Decline & Sea Peoples' Rise

Dissecting the fascinating Report of Wenamun, a detailed ancient Egyptian account of a priest's challenging voyage to Byblos for cedar. Uncover insights into Egypt's shifting power, the mysterious Sea Peoples, and maritime trade in the Late Bronze Age.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-14 | Last Updated 2025-07-14 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 2,300 times

Credit: The Barque of Amun - The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Voyage of Wenamun: A Tale of Shifting Powers

Most experts consider The Report of Wenamun a work of literature or historical fiction, rather than a completely accurate historical record. It vividly illustrates a significant shift in power dynamics, showing how Byblos's ruler no longer felt obligated to simply hand over timber at Egypt's command. The report describes a challenging verbal exchange and highlights Wenamun's lack of official letters, underscoring the breakdown of the established system we see in the earlier Amarna period. Unlike Homer’s Odyssey, a purely fictional story, the Report of Wenamun was based on a real voyage.

A papyrus, found stuffed into a pot somewhere south of Cairo and now, oddly, housed in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, recounts a journey that happened around 1075 BC. We call this account ‘The Report of Wenamun.’ Like many texts from that era, it mixes literary flair with historically verifiable facts. If we look past the tumultuous storms, sea monsters, alluring seductresses, and glamorous female protectors, we uncover an incredible snapshot of maritime trade between Egypt and Byblos at the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period (1077 to 943 BC).

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Mission Begins

Wenamun, an Egyptian priest, embarked on a mission to get cedar wood from Byblos. He needed it to rebuild Amun's sacred boat. He set off with recommendation letters from the High Priests of Amun at Thebes, who, after 1077 BC, ruled Middle and Upper Egypt. He also carried a quantity of silver and gold to barter for the wood.

Early Setbacks and a Thief in Dor

Even before leaving the Nile Delta, Wenamun ran into problems with Smendes, the ruler of Lower Egypt (and founder and pharaoh of the first Dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian Third Intermediate Period). Smendes confiscated Wenamun's introduction letters and delayed his passage through the Delta.

Nevertheless, Wenamun pressed on, traveling on a foreign ship Smendes arranged. He left the Delta and sailed up the south coast of the Levant as far as Dor in northern Israel. At that time, Dor was a teeming port with a quay about 35 meters long. You can still see the remains of this quay today; it's the oldest surviving one in the Mediterranean. When Wenamun's ship docked at Dor, a seaman from the vessel ran off with Wenamun’s gold and silver.

Dor was ruled by the Tjeker, one of the "Sea Peoples" groups. Wenamun appealed to Beder, the Tjeker prince of Dor, to recover his stolen goods pleading, "I have been robbed in your harbour. Now you are the prince of this land, you are the one who controls it. Search for my money! Indeed, the money belongs to Amen-Re, King of Gods, the lord of the lands. It belongs to Smendes; it belongs to Herihor, my lord, and [to] the other magnates of Egypt. It belongs to you; it belongs to Weret; it belongs to Mekmer; it belongs to Tjekerbaal, the prince of Byblos!" Beder would have none of it, saying, "Are you serious? Are you joking? Indeed, I do not understand the demand you make to me. If it had been a thief belonging to my land who had gone down to your ship and had stolen your money, I would replace it for you from my storehouse, until your thief, whatever his name, had been found. But the thief who robbed you, he is yours, he belongs to your ship. Spend a few days here with me; I will search for him."

Needless to say, the thief was not caught.

Wenamun had to leave empty-handed. This left Wenamun without protection, save for a small figurine of Amun, his travelling god, similar to one found on the Uluburun shipwreck.

A Difficult Reception in Byblos

Model of a Byblos ship c 1050 BC

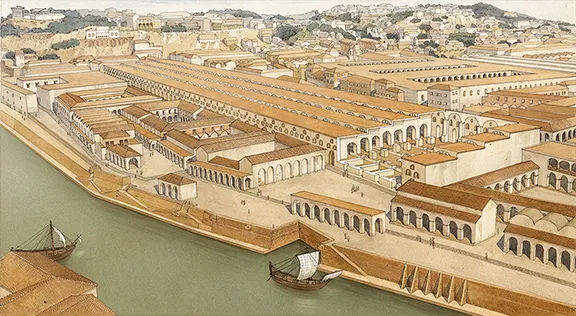

The report doesn't say how Wenamun managed to continue, but he headed north via Tyre and Sidon, eventually reaching Byblos. In Sidon, Wenamun recorded fifty ships bound for Egypt being loaded or unloaded, and another twenty in Byblos. Zakar-Baal, the lord of Byblos, made Wenamun wait a whole month before granting him an audience. Without his letters, and relying only on pleas to ancient customs, vague threats about Egyptian overlordship, and blessings from Amun, Wenamun couldn't convince Zakar-Baal to provide any timber.

Clearly, Zakar-Baal wasn't intimidated by an Egypt that no longer held supreme power in the region. He demanded valuable goods upfront, not just promises, before he would allow any cedar to be cut. He pointedly mentioned the high value of cargoes sent to his predecessors as gifts and in exchange for goods when Egypt was at its most powerful in the region, likely referring to the Amarna period between 1353 and 1322 BC.

Payment and Departure from Byblos

Wenamun sent a message to Smendes. Three months later—eight months after Wenamun had left Thebes—a ship arrived carrying gold, silver, linen, beef, fish, lentils, and rope. Smendes's wife also sent a personal package of food and clothes on the arriving ship. We can only assume that Zakar-Baal's hospitality didn't extend much beyond providing meagre rations for visiting Egyptian envoys.

While Wenamun waited, Zakar-Baal "entertained" him by showing him the graves of earlier envoys who had been detained until they died.

Finally, satisfied with the payment, Zakar-Baal ordered 300 lumberjacks and as many oxen into the mountains.

A Perilous Journey Home to Thebes

With his ship loaded with cedar, Wenamun set sail for Egypt, narrowly avoiding a squadron of Tjeker ships from Dor that were patrolling offshore, seemingly with the intention of stealing his cargo. Remember, the Canaanite city-states competed fiercely. In this case, that competition essentially amounted to piracy on the high seas. A curious detail in the account mentions Zakar-Baal sending an Egyptian entertainer named Tinetnit, along with mutton and wine, to cheer up the now disheartened traveller.

Unfortunately for Wenamun, after dodging the Dor patrol, adverse winds blew his ship northwest, causing him to make landfall on Cyprus. Here, we learn that a vengeful mob was waiting for the "Byblos ship." Only an Egyptian-speaking woman (beautiful, of course) saved Wenamun, taking him into her home. In those uncertain times, the unexpected arrival of a foreign ship clearly caused some alarm on Cyprus. Was this Egyptian lady an agent for Egyptian traders to Cyprus? Sadly, we'll never know. The report tantalisingly breaks off with the lady saying, “Spend the night….”

Wenamun did eventually make it back to Thebes, as inscriptions at Karnak celebrating the inauguration of Amun's new boat confirm.

Beyond the Narrative: Key Insights from Wenamun's Report

The Report of Wenamun, despite its literary flair, offers invaluable glimpses into the political, economic, and cultural landscape of the ancient Near East during a turbulent period:

Egypt's Diminished Power: The most striking insight is the stark decline of Egyptian influence abroad. Although the Egyptian kingdom extended up the Levantine coast as far as Carchemish, so included Byblos, Sidon and Tyre, Wenamun, representing the once-mighty pharaoh, receives disrespectful treatment and must negotiate rather than command. This contrasts sharply with earlier periods, such as the Amarna Age, where Egyptian dominance was unquestioned.

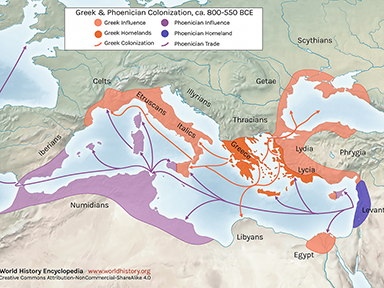

The Rise of Local Powers: The story demonstrates the emergence of independent city-states like Byblos and Dor, each with its own authority and interests. Zakar-Baal's detailed accounting of past payments highlights a shift from tributary relations to a more transactional, market-driven trade system.

The Sea Peoples and Maritime Instability: The prominent role of the Tjeker people in Dor, who appear as rulers and later as potential aggressors seeking to seize Wenamun's ship, provides crucial insight into the "Sea Peoples." These mysterious groups caused widespread disruption across the Mediterranean around this time, and Wenamun's report is one of the few contemporary accounts to name a specific Sea People group and describe their active presence and maritime capabilities. This detail vividly illustrates the instability and changing maritime dynamics of the era, where even a religious envoy could become a target of what amounted to state-sanctioned piracy.

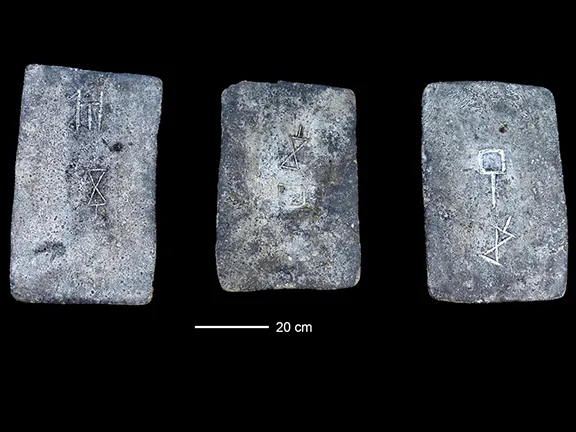

Economic Realities of Trade: The detailed list of goods sent from Egypt to Byblos (gold, silver, linen, beef, fish, lentils, rope) offers tangible evidence of the types of commodities exchanged in international trade. It also underscores the importance of silver as a primary currency in the Levant.

Cultural Exchange: The presence of an "Egyptian speaking Egyptian lady" in Cyprus, who rescues Wenamun, suggests established communities of Egyptians living abroad and the broader cultural intermingling across the Mediterranean.

Literary Sophistication: Scholars consider Wenamun a masterpiece of Late Egyptian literature. Its sophisticated use of dialogue, irony, and character development, particularly in the exchanges between Wenamun and Zakar-Baal, reveals a high level of literary artistry. It also serves as a poignant commentary on the frustrations of those clinging to an idealized past in a rapidly changing world.

These elements make Wenamun's journey far more than just a simple quest for wood; it's a window into a pivotal moment in ancient history.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution