Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

From Trading Post to Emporium in the Mare Nostrum

The words trading post, colonies and emporium are sometimes loosely used in the context of the ancient maritime trading networks. So how do you tell the difference?

By Nick Nutter | Last Updated 2023-10-11 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 1,262 times

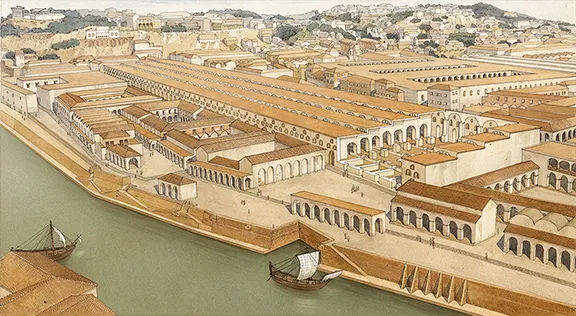

Artists impression of Roman Emporium

The terms trading post, colony, and emporium are all used to describe places where trade takes place, but there are some important distinctions between them.

Trading Post

As time passed, the first landing places recognised by both native and foreigner as places to rendezvous at which periodic exchanges of goods could take place, developed into permanent or semi-permanent settlements if they had not been so when the traders arrived. At some point in that settlement’s development, the traders started to leave representatives behind, first as administrators tasked with arranging the next cargo for instance, then perhaps specific tradesmen, potters, metalworkers and so on. Trading posts would be staffed by a small group of merchants and traders, who may be employed by a chartered company or by a government.

Colony

A colony is a settlement that is established by a foreign power in a new territory. Colonies are typically larger and more permanent than trading posts, and they sometimes had their own government and economy. Colonies may be established for a variety of reasons, including to exploit resources, to establish a military presence, or to spread religion.

Emporium

Hongs at Canton 19th century AD

Emporia (the plural of the word emporium) were ancient trading posts, factories, or markets. The Latin word emporium comes from the Greek word emporion.

An emporium is a large and prosperous trading centre. Emporiums are typically located in major cities or on important trade routes. They are often characterized by their large markets and warehouses, and by the diversity of goods that are traded there. Emporiums may be controlled by a government, by a chartered company, or by a group of private merchants.

Ancient emporia operated in a similar fashion to the Treaty Ports of the 19th and 20th centuries, the most famous of those being Shanghai where the United Kingdom, United States of America and France had trading concessions. Foreigners all lived in prestigious sections newly built for them on the edges of existing port cities in discreet areas sometimes called cantons or factories (Canton was the first Chinese port to open itself up to trade from the West). They enjoyed legal extraterritoriality, although, technically, they had to obey Chinese laws.

Perhaps the most inclusive Treaty Port was that at Beihai in Guangxi Province where merchants from the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Germany, Austria-Hungary, France, Italy, Portugal, and Belgium all rubbed shoulders and conducted business from 1876 until the 1940s.

The founding of various ancient emporia generally necessitated some negotiation with the ruling powers in the host country. Some emporia were set up on previously unoccupied land and some at existing settlements. The advantages for the host country were potentially huge since they were given direct access to new technology and exotic products from the eastern Mediterranean. For the trading nation, they gained a neutral base and a new customer base for their products as well as access to materials in demand in the eastern Mediterranean. Once established, emporia attracted the traders from other nations who could be charged taxes by the founding nation.

Distinguishing between ancient trading posts, colonies and emporia

It is often difficult in the ancient world to make the distinction between trading post, colony, and emporium. Many of the so-called colonies established by the Minoans, Greeks, and Phoenicians that litter modern maps of the ancient Mediterranean Sea would have been little more than trading posts. It is always a matter of debate as to whether the ancient trading posts became colonies as we know them.

My own view is that a trading post becomes a colony when it can be proved that there is a substantial permanent foreign population engaged in the conduct of trade. Who governs the colony is to some extent irrelevant.

A colony becomes an emporium when it can be proved the colony governs itself or is governed from a foreign country and that it allows trade from diverse other societies and countries and is itself multi-ethnic.

Minoan Trading Posts

Minoan trading posts identifed by presense of Linear A script

It is debateable whether the Minoans (a name introduced by Arthur Evans in the early 20th century), ever established anything more than trading posts outside their own homeland, the island of Crete.

While some sites on Crete seem to have been politically and economically linked, it is not clear whether there was ever even a unified Minoan state or states.

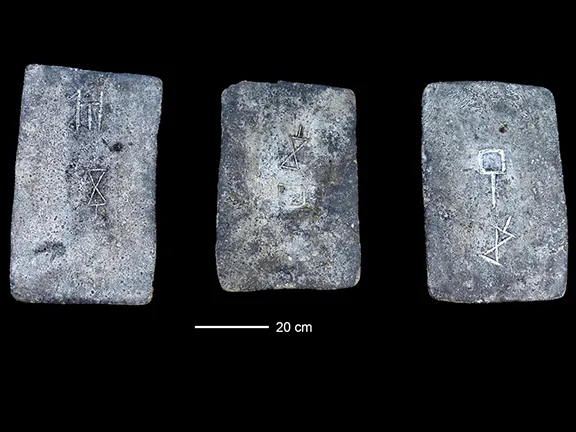

However, between c 1925 and 1450 BC, their influence in terms of pottery and art spread extensively around the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. They exported agricultural products and luxury crafts, often in exchange for raw metal which was difficult to obtain on Crete. Through traders and artisans, their cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the Cyclades, Cyprus, Egypt, Italy, Anatolia, and the Levant. Minoan craftsmen were employed by foreign elites, for instance to paint frescoes at Avaris in Egypt. The Minoans established a naval supremacy in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean that the Greeks later called a thalassocracy. The Minoan thalassocracy reached its height between 1550 and 1450 BC. After c. 1450 BC, they came under the cultural and perhaps political domination of the mainland Mycenaean Greeks, forming a hybrid culture which lasted until around 1050 BC.

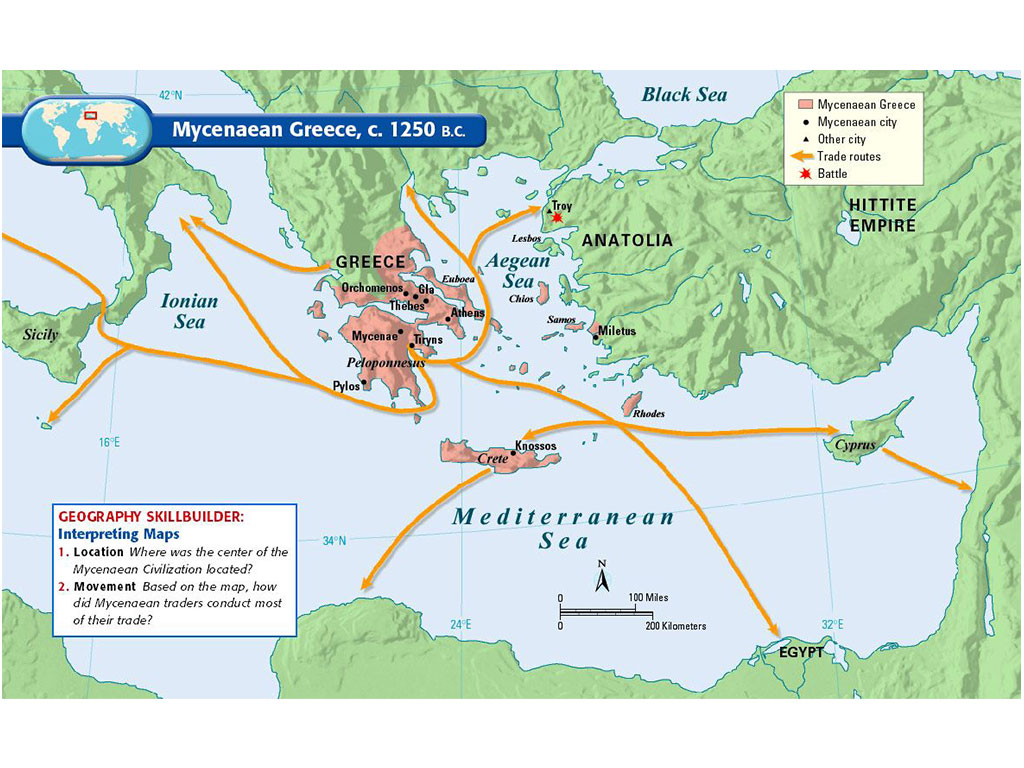

Mycenaean Trading Posts

Mycenaean Trading Posts

Beyond trading relations, the exact political relationship between the over 100 Mycenaean centres spread across Greece is not clear, so it is unlikely that they ever had anything other than trading posts overseas. They are perhaps best known for their trade in distinctive Mycenaean pottery in return for ivory, copper, and gold.

Interlude

Until about 1200 BC there had been a few groups of traders who concentrated on the eastern Mediterranean. None had yet managed to penetrate to the west themselves, trade and exchange was via traders who operated within their own restricted orbits, apart from the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Even so, small amounts of exotic goods found their way from the east to the west having probably passed through dozens of hands in their journey. Likewise, locally operating traders were also bringing goods from North Africa to the southern Iberian Peninsula. Then about 1200 BC disaster struck for the growing civilisations in the east. A succession of invasions from the north between 1200 and 1150 BC, possibly sparked off by drought and famine, led to the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdom, Hittite Empire, and the New Kingdom of Egypt. This is the period when the great cities in the east, such as Troy, were razed.

The trading/exchange/tribute economy collapsed, and it would be a few years before it rejuvenated itself and when it did there were two main contenders for the trade by sea. Greeks and Phoenicians. Instead of concentrating solely on the eastern Mediterranean both headed to the far west, beyond Sardinia, spurred on by the demand for copper, silver and gold from the newly emerging civilizations in the Near East.

After a couple of exploratory probes into the area the Phoenicians made a bold move, leapfrogging ahead of any competition. They established their first settlement at Cadiz on the Atlantic coast of southern Spain. Gades as they called it, was an ideal place to take advantage of the Atlantic Bronze trade, the metal rich Sierra Morena mines in what is now Huelva province and supply the indigenous population in the interior of the Iberian Peninsula, particularly those living in the fertile Guadalquivir and Guadiana River valleys.

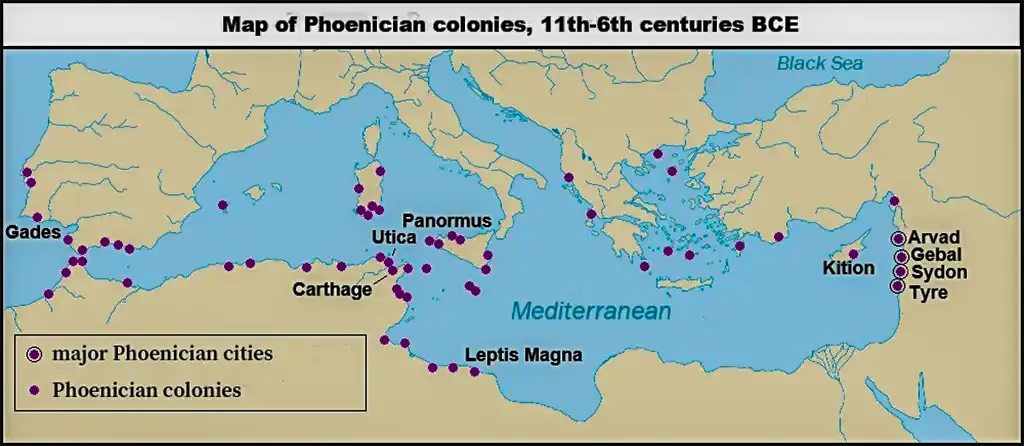

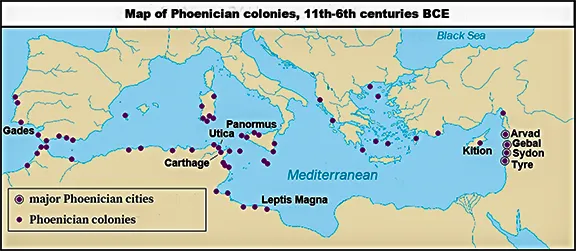

Phoenician Colonies

The Phoenicians developed their trading network from the city states of Arvad, Gebal (Greek Byblos), Sidon and, the most famous of them all, Tyre from about 3500 BC when they are recorded to have been trading with the Egyptians. It was only after the collapse of the Mycenaean kingdom, Hittite Empire, and the New Kingdom of Egypt, that the Phoenicians became true long-distance mariners.

The question is whether those trading posts every grew to become colonies or emporia. A glance at the map above will show you just how many trading centres are recognised as colonies today due to the number of Phoenicians evidently in residence at some time during the 1st millennium BC. Of those colonies a few, strategically placed, such as Kition, now Larnaca on Cyprus and Gades may be considered emporia.

The Phoenicians liked to establish their trading posts and colonies on peninsulas or islands just offshore that offered shelter to their boats that would, typically, be simply drawn up on a beach. From time immemorial such places on the littoral between land and sea could be recognised by the local inhabitants and visiting traders as neutral ground. Being surrounded by sea on at least three sides and, in the case of peninsulas, having only narrow access to the mainland, they were also easily defended if necessary. In some cases, ideal spots were already occupied or visited regularly by local inhabitants who, during this period were primarily agriculturists and herders of sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle. A small island or a narrow peninsula would not have been their ideal locale for a settlement. It makes you wonder if at least some of those previously occupied sites were not deliberately created to serve incoming traders, at first from the local coastline and then from more long-distance destinations.

The numbers of Phoenicians emigrating from their homeland were boosted after 858 BC when their city states came under the vassalage of the expanding Assyrian and Babylonian kingdoms until 538 BC, then the Persians from 539 to 332 BC. Most of the Levant was consolidated by Cyrus the Great, king and founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, into a single satrapy (province) and forced to pay a yearly tribute of 350 talents, which was roughly half the tribute that was required of Egypt and Libya. The tribute stimulated more trade with the west, particularly in silver.

In 332 BC Phoenicia was one of the first areas to be conquered by Alexander the Great during his military campaigns across western Asia. Alexander's main target in the Persian Levant was Tyre, then the region's largest and most important city. It capitulated after a roughly seven-month siege, during which many of its citizens fled to Carthage.

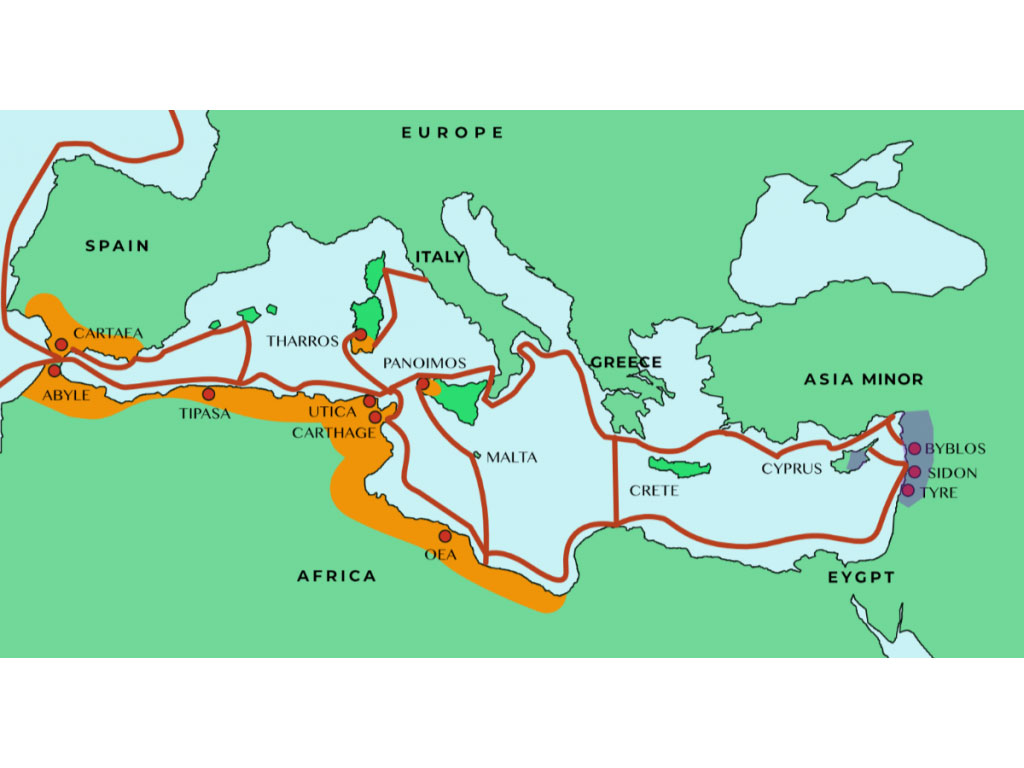

Carthaginian Colonies

Carthaginian colonies

The breakdown of the Phoenician homeland after 858 BC encouraged one group of Phoenicians to become independent of the home city state, Tyre.

A group of merchants from Tyre established a colony at Carthage on the Tunisian coast opposite Sicily around 814 BC. This was a deliberate attempt to keep control of trade in the central Mediterranean. The Greeks were establishing their own trading posts, at first in the Adriatic with Corcyra on Corfu about 733 BC. Then they expanded to Italy and Sicily. The Greek settlement at Syracuse on Sicily was established as early as 733 BC.

Carthage grew into a sizeable city and its population started to found its own colonies on the coast of North Africa. Carthage began to challenge Tyre both in size and influence and, because they were prepared to defend their trade routes from the Greek threat, began to build an armed presence in the central Mediterranean.

They used their wealth from trade to build a fleet of warships and adopted a much more militaristic attitude to those they considered a threat than had the Phoenicians.

No longer were tributes paid to Tyre or Sidon, the Carthaginians appointed magistrates in the towns they colonised, including those previously considered Phoenician. The magistrates ruled the towns and answered directly to Carthage. The towns had developed from colonies by virtue of their population alone to colonies by virtue of population and foreign control.

It was about 650 BC that the traders of Carthage took their first action sanctioned by leaders from Carthage rather than Tyre. They colonised Ibiza, establishing a base between the Greeks on Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula. It is from this point that Carthage can be considered a separate power.

But did their colonies ever gain the status of emporia? The Carthaginians were very protective of their territory, colonies, and trade routes. There is little evidence during the Carthaginian period of ‘foreign’ ships appearing in many Carthaginian colonies. However, some exotic goods from the east did arrive in the west.

My own view is that major colonies on the boundaries of Carthaginian influence such as Leptis Magna on the coast of North Africa, Panormus (now Palermo on Sicily), Cartagena on the Iberian Peninsula, and Gades on the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula were interacting with local traders and the Greeks thus allowing eastern products through to the west even if not carried the whole distance on a vessel owned by one nation or merchant.

Greek Emporia

Greek colonies and emporia

Of all the ancient maritime nations, the Greeks must be pre-eminent in their colonising endeavours. There can be little doubt that, of the colonies they established, a number became emporia.

From about 800 BC the various Greek tribes expanded through the founding of colonies overseas. This was a determined and coordinated effort to carve out a trading Empire. The coasts and islands of Anatolia were occupied from south to north by the Dorians, Ionians, and Aeolians, respectively. In addition, individual colonies were strung out around the shores of the Black Sea in the north and across the eastern Mediterranean to Naucratis on the Nile delta and in Cyrenaica and in the western Mediterranean by the Phocaeans in Sicily, southern Italy, and Massalia (Marseille).

Thus, the Hellenes, as they called themselves thereafter, came into contact on all sides with the old, advanced cultures of the Middle East and transmitted many features of these cultures to western Europe.

We know quite a lot about some of these colonies and how they were administered. They include: Naucratis and Thonis-Heracleion in the Nile Delta, Marssalia in southern France, and Empúries in northeastern Spain.

Do you enjoy my articles? You could help me write more by buying me a cup of coffee.

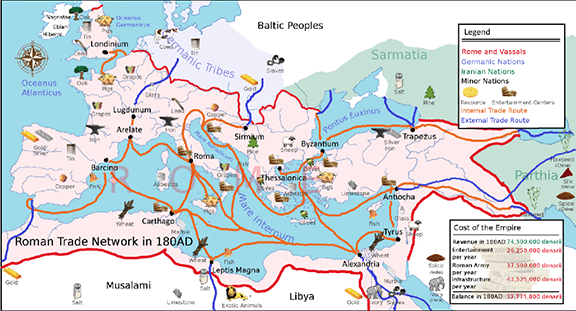

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: Ancient Sea Trade Routes in the Mediterranean Sea

2: Ancient Sea Trade Routes in the Mediterranean Sea 3: The Tin Roads

3: The Tin Roads 5: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 8th c BC - 8th c AD

5: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 8th c BC - 8th c AD 6: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis c 664 BC - c 700 AD

6: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis c 664 BC - c 700 AD 7: The Greek Emporium of Empúries 575 BC - 3rd c AD

7: The Greek Emporium of Empúries 575 BC - 3rd c AD