Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

Expanding the Ancient World: Pytheas of Massalia's Arctic Voyage (325 BC)

Pytheas of Massalia's audacious 4th-century BC voyage beyond the Mediterranean to find new trade routes to northern Europe. Explore the known world of 325 BC, Pytheas's journey to Britain and the Arctic, and the controversy following publication of his On the Ocean.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-13 | Last Updated 2025-07-13 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 3,289 times

Pytheas of Massalia - Statue in Marseille

Expanding the Known World in 325 BC with Pytheas of Massalia

The human drive to explore, to chart what lies beyond the horizon, is a timeless impulse. In 325 BC, this innate curiosity propelled figures like Pytheas of Massalia into the vast unknown, profoundly transforming the Hellenic understanding of the world. Yet, the map of human knowledge upon which Pytheas built his expedition was itself the culmination of centuries of daring ventures. From the ancient Egyptian expeditions to the mystical Land of Punt (c. 1492 BC), to the legendary Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa (c. 600 BC) and Hanno the Navigator's southward push along the African coast (5th century BC), humanity steadily charted its immediate surroundings. Likewise, land expeditions, such as Cyrus the Great's expansion into Central Asia (550-530 BC) and Skylax of Caryanda's survey of the Indus (c. 515 BC), alongside Xenophon's famous 'March Up Country' (c. 431-354 BC), had broadened the eastern horizons.

By 325 BC, this accumulated knowledge formed a distinct, albeit incomplete, picture. It was a world shaped by generations of philosophical thought, the practicalities of trade, and the tales of intrepid travellers, often blending verifiable fact with speculative geography.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Early Explorers

Voyage of Euthymenes

The knowledge of the known world was built on the deeds of explorers and warriors from as early as 2500 BC. Their motivations were either to expand trading routes, find alternative routes, or expansion of their empires.

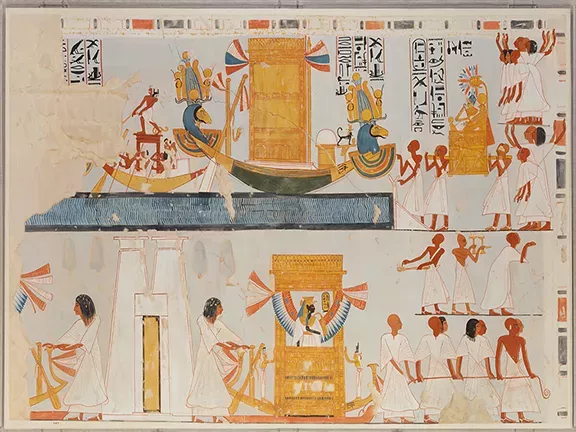

Hatshepsut’s Expeditions to Punt (c 1492 BC)

The Egyptians frequently sent fleets to the mysterious "Land of Punt," likely located on the African coast of the Red Sea (possibly modern Eritrea or Somalia), to acquire exotic goods like frankincense, myrrh, gold, and exotic animals. Reliefs in Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el-Bahari vividly depict this expedition.

Circumnavigation of Africa (c 600 BC)

The Greek historian Herodotus recounts how Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II commissioned a Phoenician expedition that supposedly circumnavigated Africa, sailing from the Red Sea, around the continent, and back into the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar. Herodotus himself expressed scepticism but noted a detail that lends credence: the Phoenicians reported seeing the sun on their right side (to the north) when sailing westward along the southern coast of Africa, which would be true south of the equator.

Euthymenes of Massalia (600 – 550 BC)

Euthymenes of Massalia was an early Greek explorer likely from the early to mid-6th century BC, undertook a significant maritime expedition down the Atlantic coast of West Africa. Although his original Periplus is lost, later ancient authors, such as Plutarch (46 – 120 AD) and Seneca the Younger (4 BC – 65 AD), recount his encounter with a vast river whose outflow noticeably freshened the sea, leading him to mistakenly identify it as a western mouth of the Nile. Modern scholars widely interpret this as an observation of the Senegal River, making Euthymenes one of the earliest documented European explorers to extensively navigate the West African coast and demonstrating Massalia's pioneering spirit in charting the limits of the known world long before Pytheas's northern venture.

Cyrus the Great's Exploration of Central Asia (550 – 530 BC)

The Persian Empire's expansion under Cyrus the Great and his successors meant Greek mercenaries, historians, and geographers often accompanied or documented these vast land explorations, pushing the known boundaries into Central Asia and the Steppe lands.

Skylax of Caryanda (c 515 BC)

A Greek navigator from Caria, Skylax was commissioned by the Persian King Darius I to explore the Indus River from its mouth to its source, and then to sail from the Indus delta through the Indian Ocean to Egypt. This ambitious journey provided the Persians with vital geographical knowledge of the eastern fringes of their vast empire.

Hanno the Navigator (5th century BC)

Hanno, a Carthaginian, led a large naval expedition down the west coast of Africa. His Periplus (sailing account), inscribed on a stele, describes encountering various peoples, dense forests, and even active volcanoes ("Chariots of the Gods"). Scholars debate how far south he reached, with estimates ranging from modern-day Senegal to as far as Cameroon. His voyage aimed to establish new Punic colonies and secure trade routes.

Xenophon (c 431-354 BC)

Though primarily a military general and historian, Xenophon's "Anabasis" (The March Up Country) vividly recounts the journey of 10,000 Greek mercenaries deep into the Persian Empire and their arduous return. This narrative provided invaluable geographical and ethnographical detail of regions largely unknown to the average Greek.

As a result of these and other explorations, the Greeks had a picture of their known world.

The Known World in 325 BC

Herodotus view of the world

Despite military and trade explorations over the preceding centuries, the Greek view of the world had changed little since the time of Herodotus in 450 BC.

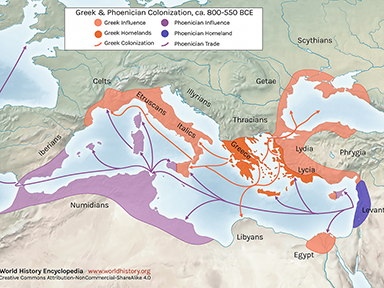

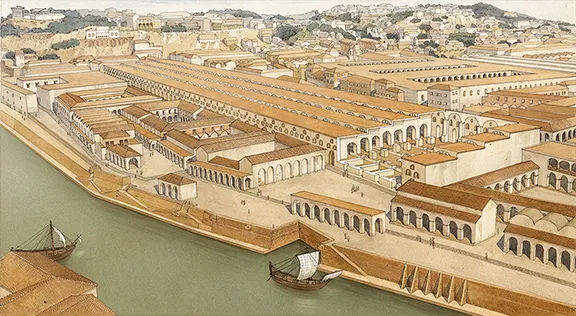

At the heart of the known world lay the Mediterranean Basin. This dynamic sea functioned as the central nervous system of antiquity, connecting the disparate cultures of Southern Europe, North Africa (then referred to as "Libya"), and the Near East. Greek city-states, and the formidable maritime empire of Carthage had long navigated its waters. Ships from bustling Phoenician ports, such as distant Tyre and Sidon, regularly plied these routes, arriving and departing daily, their hulls laden with goods. Every island, every major coastline, and every significant settlement within this great sea held a place on the scrolls of geographers and within the collective consciousness of its inhabitants. Trade routes crisscrossed its expanse, moving goods, ideas, and people with a relatively high degree of navigational certainty.

Beyond this familiar expanse, knowledge gradually dissolved into uncertainty.

In Europe, the Hellenic heartland, along with its extensive colonies in Southern Italy and Sicily, was meticulously mapped and deeply integrated into Greek thought. Further north, the emergent power of Macedon, now under Alexander the Great, commanded a significant presence in the Balkans. Beyond these well-trodden paths, the information became sparser.

The Iberian Peninsula, for instance, saw Greek and Punic trading posts dotting its coasts, most notably Gades (modern-day Cádiz) at its western edge on the Atlantic coast, with Malaka (Malaga), Sexi (Almunecar) and Abdera (Adra) on the Mediterranean coast, yet its interior remained a largely mysterious land populated by "barbarian" tribes.

The same held true for Gaul, the vast land corresponding to modern-day France. The Mediterranean coastline, home to Pytheas’s own Massalia (Marseille), maintained strong connections with the Greek world. While ancient overland trade routes certainly traversed its interior, connecting the Mediterranean with Atlantic resources, direct Greek maritime knowledge of Gaul's western shores was minimal before Pytheas's journey.

Further north still, the British Isles, then referred to as "Pretannia" or "Albion," existed on the very fringes of understanding. These islands were known primarily as distant sources of precious tin, crucial for bronze production, but their exact size, shape, and precise location often remained shrouded in myth, bordering on the realm of fantastical lands at the world’s very edge. Regions beyond Britain, such as the fabled "Thule" and the concept of a "congealed sea" – descriptions of Arctic ice – existed purely as vague rumours of extreme cold and unusual daylight patterns, their existence largely unverified by direct observation.

Africa presented its own set of knowns and unknowns. The fertile northern coastal strip, particularly the powerful Carthaginian territories and the ancient civilization of Egypt along the Nile, was well-documented through centuries of interaction and trade. Yet, the colossal barrier of the Sahara Desert effectively sealed off the interior, creating a vast "terra incognita" that stretched south. Accounts of "Aethiopia" often referred to lands south of Egypt, but their specific geography remained largely indeterminate, a source of both speculation and wonder.

To the east, Asia presented a dramatically shifting landscape of knowledge. The ancient Near East, encompassing Anatolia, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Persia, had long been a region of immense historical significance and cultural exchange.

By 325 BC, this entire vast territory had been fundamentally reshaped by Alexander the Great's relentless campaigns. His armies, meticulous in their record-keeping, pushed the boundaries of Greek knowledge deep into Central Asia and northwestern India, bringing Hellenic scholars into direct, unprecedented contact with previously distant civilizations. Alexander's expeditions meticulously mapped river systems, established new cities, and documented the myriad peoples encountered along their astonishing eastward thrust. Beyond India, however, lands like China, known vaguely as "Serica" for its valuable silk, remained an ethereal concept, glimpsed only through the earliest, tenuous strands of indirect trade routes.

The Greek Cosmological View

Underpinning this geographical understanding was the prevailing Greek cosmological view, which held that the known landmasses of Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa) were entirely surrounded by a single, continuous, world-encircling body of water, the Oceanus. This grand, unifying concept defined the ultimate boundaries of their maps and their imagination. The precise extent and navigability of this colossal ocean remained largely theoretical, a final frontier awaiting brave and curious minds.

It was into this complex and incomplete world that Pytheas of Massalia stepped, driven by a desire to challenge the conventional wisdom and to physically touch the edges of the known world.

Pytheas of Massalia: An Ancient Journey Beyond the Known World

Who was Pytheas?

In an age dominated by military conquests and the expansion of empires, Pytheas, a Greek from the thriving port city of Massalia had a different kind of ambition.

Born in an era when Alexander the Great was reshaping the East, Pytheas was not a general or a conqueror, but a geographer, an astronomer, and above all, a meticulous observer. His early life, like many figures from antiquity, remains largely in shadow.

Many historians think that Pytheas was contracted to undertake his voyage by wealthy Greek merchants from their colony at Massilia.

His singular voyage, undertaken around 325 BC, was an exceptionally audacious feat of ancient exploration, propelled by pecuniary interests and intellectual curiosity, not military might. Pytheas sought to find new trading partners for the Greek merchants of his home town, push the boundaries of established geography, to verify fantastical tales of distant lands, and to apply scientific rigour to the very edges of the known world.

The prevailing geographical wisdom of the time often placed the British Isles, distant sources of highly prized tin, as a vague, semi-mythical archipelago. Pytheas sought to replace rumour with first hand observation. His expedition aimed to reach these fabled lands, to understand their geography, their people, and the very nature of the ocean that separated them from the Mediterranean.

Alternative Routes to the Atlantic

The Carthaginians controlled the supply of crucial metals such as tin, copper, silver and gold that originated in Galicia in northwestern Spain, and Huelva in southern Spain. These commodities were delivered to their Atlantic trading posts in Portugal and southern Spain. The cargoes were passed on via the Greek trading posts in Iberia and Sicily to the Aegean. Their blockade of the Straits of Gibraltar made it difficult or dangerous for competitors to source this market.

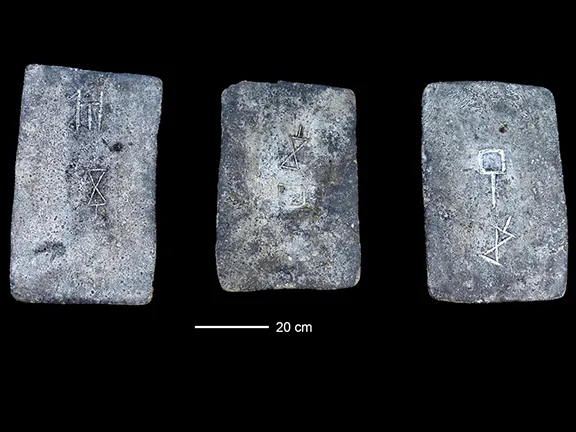

Meanwhile, small amounts of metals, particularly tin, had been finding their way from Cornwall via overland routes to the eastern Mediterranean since before 2000 BC. Evidence of a direct tin trade between Europe and the eastern Mediterranean has been demonstrated through the analysis of tin ingots dated to the 13th-12th centuries BC from sites in Israel, Turkiye, and modern-day Greece; tin ingots from Israel, for example, have been found to share chemical composition with tin from Cornwall and Devon.

A thousand years before Pytheas embarked on his voyage, a shipwreck occurred at Hishuley Carmel, Israel. On board were tin ingots from Cornwall and Devon. This was confirmed by a study published in the journal Nature Communications in 2022, which used a combined approach of tin and lead isotopes together with trace elements to narrow down the potential sources of the tin.

As we shall see later, the tin travelled by ancient Celtic trade routes through Central Europe.

The Greek merchants in Massalia wanted to use equally well-established overland routes through western Europe to bring precious metals directly from their sources in Brittany and Cornwall to Massalia on the Gulf of Lion. Any of the paths taken by Pytheas to cross Gaul would have allowed him to look at the feasibility of a direct overland link between Brittany and Massalia.

Route 1 - Through the Pillars of Hercules

Many popular accounts depict Pytheas sailing directly through the formidable Strait of Gibraltar, the "Pillars of Hercules.” There are two reasons why this may not have been wise or even possible in 325 BC.

Carthaginian Domination of the Straits The Pillars was a gateway notoriously controlled by the Carthaginian empire. Carthage, a formidable naval power, frequently restricted access to the Atlantic, eager to protect its lucrative trade monopolies. Navigating through their controlled waters would have posed significant political and military risks.

The Bay of Biscay as a Hazard to Navigation Even today, a transit of the Bay of Biscay is a hazardous undertaking for sailors. The UK Admiralty Pilot describes the navigational hazards of the Bay in some detail to ensure the safety of mariners. The hazards include severe weather and rough seas, strong winds and squalls, strong tidal currents and ranges, lack of safe havens and notorious capes and headlands.

Prior to Pytheas, there is no physical evidence that the so called ‘Atlantic Bronze Age’ trade routes, developed from about 1300 to about 700 BC, included direct maritime connections across the Bay of Biscay between A Coruna in Galicia and Brest in northwest France. The Atlantic Bronze Age trade routes were, in effect, two separate entities that met at the Gulf of Lion in the Mediterranean. One undoubtedly went overland between the Gulf of Lion and the Gironde estuary and further north to the Loire estuary and thence to Bay of Mont-Saint-Michel. The other was an inshore maritime route from the Gulf of Lion, west along the Iberian coastline, through the Straits of Gibraltar and along the Atlantic coast of Spain and Portugal as far as Galicia.

As far as we know, even the Phoenicians did not attempt a crossing of the Bay of Biscay, their northernmost colony was Olisipo (Lisbon) on the Atlantic coast of Portugal.

Plus, it is unlikely that any ship design of 325 BC was sturdy enough to cross the Bay of Biscay safely, although, by 58 BC, according to Julius Caesar, the Veneti tribe in Brittany, had developed oak built ships with leather sails that could brave the Atlantic Ocean and Bay of Biscay and that were far superior in seakeeping qualities to the lighter Mediterranean ships. It is possible that an earlier version of these ships were available to Pytheas on his journey from Brittany to Britain.

Route 2 - Overland through Gaul

Consequently, a compelling theory, championed by modern scholars such as Professor Barry Cunliffe, suggests that Pytheas likely chose a more strategic approach: an overland passage through Gaul.

This alternative route would have seen Pytheas travel from Massalia up the Aude River, then cross a relatively low watershed to connect with the Garonne River, which ultimately flows into the vast Gironde Estuary on Gaul’s Atlantic coast. An alternative route from Massalia is up the Rhone and across to the Loire. The River Loire empties into the Atlantic near St. Nazaire, 250 kilometres north of the Gironde Estuary. Either route would have utilized ancient Celtic trade routes, well-established pathways for moving goods across the continent.

By reaching the Atlantic seaboard in what is now Brittany, Pytheas could have bypassed Carthaginian dominance at Gibraltar entirely, embarking on his northern sea voyage from a more secure and efficient starting point. Some scholars argue that Pytheas travelled overland through Gaul to the Bay of Mont-Saint Michel, thereby avoiding the hazardous and arduous rounding of Cape Finisterre.

The Voyage of Pytheas

Pytheas’s Circumnavigation of Britain

From the coast of Gaul, Pytheas set sail for the elusive "Tin Islands." He navigated the powerful, unfamiliar currents of the Western Approaches to the English Channel, a sea far more tempestuous than the enclosed Mediterranean. He successfully reached Britain, circumnavigating the entire island, at one point sighting Ierne (Ireland), an island whose people were said to be wild and savage. His account, fragments of which survive in later writers, meticulously described the island's triangular shape, its various peoples, and its abundant resources.

Pytheas's circumnavigation of Britain yielded remarkable ethnographic details. He observed a large population, led by numerous chiefs who deployed chariots in warfare. These islanders often adorned their bodies with blue paint or tattoos. Their dwellings were typically small structures of logs and thatch. Due to the consistently damp and rainy climate, they threshed their corn indoors within large barns. They then stored the processed grain in cellars, grinding it as needed for bread, a practical adaptation to their environment.

In Cornwall, Pytheas noted a greater than average level of sophistication among the local populace, attributing this to their regular interaction with foreign tin traders. These skilled miners extracted the valuable ore with considerable expertise. They transported it to an island named Ictis – a Celtic name, likely referring to St Michael's Mount – either by carting it across the exposed seabed at low tide or by shipping it in light boats crafted from hides. Many later historians such as Pliny writing in the 1st century AD, quoted Pytheas in their own narratives. Pliny writes: "there is an island called Mictis lying six days sail inwards from Britannia where tin is to be found. The Britons cross to the island in wicker boats sewn over with hides".

From Ictis, merchants loaded the tin onto vessels bound for Gaul, where it then travelled by horseback across the continent. Some historians assume that the small hide boats quoted by Pliny and Timaeus were used for the dangerous cross Channel route between Cornwall and Brittany.

A more likely scenario is that the ore was carried in sewn plank coastal canoes to the area of modern-day Dover and then across the English Channel at its narrowest point to Calais and from there entered the European trading networks via the River Seine or River Rhine. The Seine - Rhone route was well known in antiquity and would explain the tin found in the Rochelongue deposit in southern France dating to the 7th or 6th century BC. The tin would then enter the Sardinia, Sicily network and from there to the eastern Mediterranean. From the Rhine delta, the river Rhine to the river Danube route to the Black Sea was a known ancient trail. From the Black Sea, local craft would have taken the tin to Turkiye and the Middle East.

Either way, in 325 BC, Massalia was not part of the equation.

Pytheas’s observations of the tides were particularly striking, noting their far greater range and force compared to the Mediterranean’s calmer waters – an unmistakable sign of direct experience with the powerful Atlantic system.

He wrote that the sea round Britain rises 80 cubits (36.5 metres). He may have meant the tides in the Bristol Channel, which rise about 20 metres, or the high tides in stormy weather in the Pentland Firth. Pytheas was the first man to connect the tides with the influence of the moon, although he could not explain exactly what happened.

To the Frozen North

Beyond Britain's shores, Pytheas ventured further north, describing lands where animals were scarce or absent, and where oats served as the only cultivated grain. He noted the inhabitants survived primarily on wild fruits, vegetables, and roots.

His account also mentioned a distant island, Thule, located a challenging six sailing days north of Britain and merely one day from the "frozen" or "curdled" sea, a place where "neither walking nor sailing was possible." While some speculate Thule referred to the Shetlands or the Faroe Islands, it more plausibly points to northern Norway or Iceland. He describes phenomena of extreme day and night lengths, indicating his probable observation of the Arctic's midnight sun or extended twilight.

Pytheas likely gathered intelligence about these far-flung regions during his travels, even if he did not personally set foot on them.

Before his return journey, Pytheas aimed to pinpoint the source of amber, a highly coveted substance. While Mediterranean traders, including those from Massalia, knew that this prized fossilized resin originated from northern European coasts and islands, no explorer from the Mediterranean before Pytheas had reached Germany by sea. He recorded encountering two tribes, the Gutones and Teutons, residing along a tidal coastline and on an island named Abalus, probably Heligoland. Here, the tides washed amber ashore each spring, and the local inhabitants collected and sold it.

Pytheas, ever the astute observer, identified the origin of amber as condensed pine resin, formed by the action of cold and seawater. This contrasted sharply with earlier Greek beliefs, which held amber to be congealed seafoam or even the sun's solidified sweat.

Historians cannot trace Pytheas's journey beyond the River Elbe, and details of his return home remain unknown.

On the Ocean (Peri tou Okeanou)

On his return, Pytheas compiled his findings into a book titled "On the Ocean". Regrettably, this invaluable original work no longer exists; only fragments, preserved through quotations by later Greek geographers like Polybius (who wrote a century later) and Strabo (writing three centuries later), offer glimpses into his extraordinary expedition. And it was these later authors, particularly the influential Greek geographer Strabo, who cast a long, damaging shadow over the claims made in ‘On the Ocean’.

On the Ocean Dismissed by Strabo

Strabo, a formidable scholar in his own right, vehemently dismissed much of Pytheas's narrative as fabrication. He labelled Pytheas a "fabricator of falsehoods" and his detailed accounts "mere fables," a powerful condemnation from such a respected authority.

Why did Strabo, from the comfort of the Mediterranean world, so forcefully reject Pytheas's extraordinary claims? Strabo himself had never ventured into the far northern Atlantic. The very idea of a frozen sea, the bizarre extremes of daylight, and the existence of lands so far removed from known trade routes likely seemed too outlandish to someone whose geographical understanding was rooted in a warmer, more familiar clime. Perhaps Strabo, reliant on established philosophical traditions and second-hand reports, found Pytheas's direct, empirical observations, which often contradicted conventional wisdom, to be inherently suspect.

Pytheas Vindicated

Yet, modern scholarship has largely vindicated Pytheas. His astronomical precision, demonstrated by his remarkably accurate calculations of latitude based on the length of the midday shadow, speaks volumes of his scientific rigor. His detailed descriptions of the Atlantic tides, a phenomenon barely noticeable in the Mediterranean, could only have come from direct observation. Pytheas was not merely a storyteller; he was a pioneering scientist, meticulous in his data collection, even when his findings challenged the accepted norms of his time.

His voyage did not just expand the known world on a map; it expanded the very methodology of geographical inquiry, moving it closer to empirical science.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution