Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

Neolithic Sea Voyages: How Ancient Mariners Shaped the Mediterranean

Explore the fascinating story of Neolithic seafaring in the Mediterranean. Discover how early mariners used maritime routes to spread agriculture, trade obsidian, and colonize islands.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-03-21 | Last Updated 2025-05-26 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 4,474 times

Impressed ware from Dalmatia

Seafaring during the Neolithic in the Mediterranean

By 10,000 BC, the people of the Middle East were starting to develop Neolithic practices that would spread to the shores of the Atlantic over the following five thousand years, transforming the lives of the Mesolithic communities in Europe. The rapid expansion of Neolithic practices, particularly in the western Mediterranean could not have been achieved without resorting to the sea and using the maritime knowledge gained by the Mesolithic societies.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Neolithic Revolution at Sea: Understanding the Offshore Impact of Neolithic Expansion

We saw in the previous article (Seafaring during the Mesolithic in the Mediterranean) how the Mesolithic people in the Mediterranean Basin made the first passages across the open sea along the coasts and from coasts to islands. Their knowledge of currents, prevailing winds, landmarks, routes, and hazards enroute, was to prove invaluable to the Neolithic people that spread out from the Fertile Crescent to the furthest points west on the Iberian Peninsula.

Was the Neolithic revolution solely land-based, or did it impact seafaring?

The Neolithic revolution is usually seen as a land-based phenomenon with its impact firmly on dry ground. It is not often appreciated that the Neolithic expansion had consequences offshore as well.

Chronology of Neolithic expansion in the Mediterranean: East to West

The Neolithic period occurred at different times in different places. In the eastern Mediterranean, in the Middle East, the Neolithic period started about 10,000 BC. Jericho is often cited as the first permanent settlement from 9500 BC. On the Iberian Peninsula, in the western Mediterranean, the Neolithic period started about 6000 BC and the first permanent settlements only appeared after 4500 BC. Interestingly, the first permanent settlement, to date, appears to have been founded on San Fernando Island at Cadiz about 4200 BC. Cadiz is almost as far west as it is possible to go on the Iberian Peninsula. As a general rule, Egypt being one exception, all points between the Levant in the east and Portugal in the west, i.e. Greece, Italy, France and Spain and the major islands, Cyprus, Crete, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic Islands followed the same progression, starting at a date intermediate between the start of the Neolithic expansion in the east and the Neolithisation of the Iberian Peninsula.

The interaction between Neolithic farmers and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers

As the Neolithic spread west through the Mediterranean basin from the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East to the wave lashed shores of Atlantic Portugal, the farmers met the Mesolithic hunter gatherer people who had been part of the landscape for tens of thousands of years. In the coastal regions, the Mesolithic knowledge of seafaring, local conditions, short range routes, sources of resources not available locally, and boat building traditions was adopted by the newcomers. They consolidated and extended that knowledge, taking the existing maritime exchange routes to new destinations thereby discovering more agricultural land and resources.

How did Neolithic people enhance existing Mesolithic maritime trade routes?

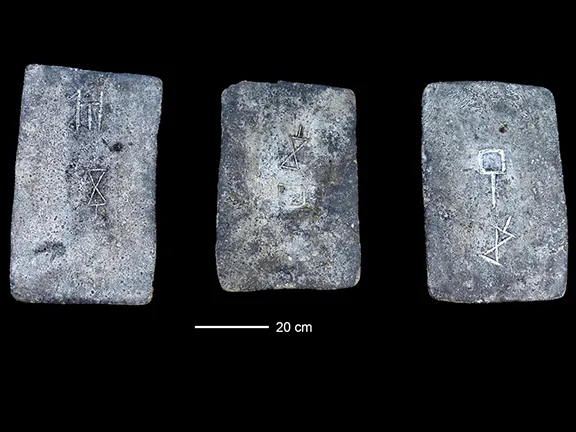

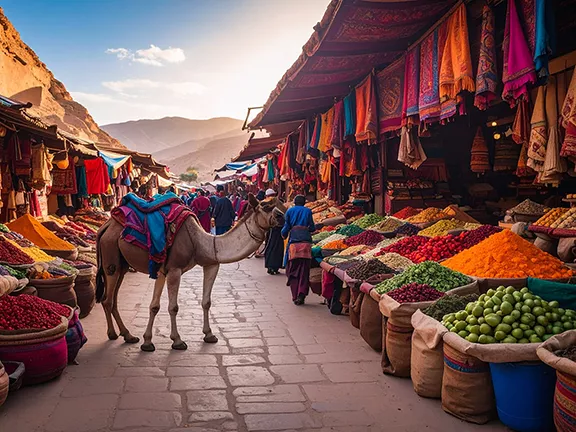

The relatively short-range maritime routes used by the Mesolithic people to garner rare materials such as obsidian, a highly valued volcanic glass, and for the purposes of exchanging goods, became more formalised routes. The range of goods being carried as cargo increased and ever more exotic objects were transported to and from increasingly far off lands.

The increasing demand for exotic goods and status symbols via sea routes

Whilst the Neolithic farmers on the western edges of that known world were forming settled communities, the societies in the Middle East were a step ahead. By 5500 BC, the societies of the Middle East were consolidating into urban centres, were beginning to use metals, and elites were emerging that demanded status enhancing products from abroad.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Eastern Mediterranean: Evidence of Early Maritime Links

The Eastern Mediterranean consists of Cyprus, the southern coast of Anatolia, and the Levantine coast.

What Evidence Exists for Neolithic Seafaring to Cyprus?

Recent excavations on Cyprus push back the island's Neolithic period to the ninth millennium BC. The findings, primarily from the Ayia Varvara Asprokremnos site, reveal that early Cypriots were participants in the broader Neolithic development of the Levant. Artefacts discovered, including ochre-stained tools, shaft-straighteners, and a clay figurine, show connections to mainland assemblages, indicating wide-ranging interaction. Radiocarbon dating confirms that the Ayia Varvara Asprokremnos site was occupied around 8800-8630 BC, bridging a previously identified gap in Cyprus's archaeological record. The initial arrival of settlers on Cyprus during the Aceramic Neolithic period (8800-6000 BC) was accompanied by the introduction of several domesticated animal species, including dogs, sheep, goats, and possibly cattle and pigs.

That a maritime link was well established between Anatolia and Cyprus is shown by the discovery of Anatolian obsidian at various places, all dated to the Cypriot Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period (8800 - 6000 BC). Shillourokambos is identified as the oldest Cypro-PPNB site, commencing around 8400 BC. It is located near the southern coast of Cyprus. Akanthou Arkosykos, located on the north coast of Cyprus, also contains abundant obsidian from Anatolia. The research does not provide a specific date for the obsidian finds at this site, but it is classified as a Cypro-PPNB site.

Similarly, at Kalavassos Tenta, Kritou Marottou, and Ais Giorkis in the western uplands, abundant obsidian was found at these sites. There is no specific date for these finds, although they are within the Cypro PPNB date range.

Archaeological evidence of Levantine connections on Neolithic Cyprus

That contact was maintained between Cyprus and the Levant is evident. The early colonies on Cyprus failed at least twice and had to be restocked with livestock from the mainland. Evidence indicates that cattle, while possibly introduced during the initial settlement phase, were relatively rare and subsequently died out on the island during the course of the 8th millennium BC. They were not re-introduced to the island until well into the Bronze Age.

Genetic studies: Tracing Neolithic migration from the Levant to Cyprus by sea

Genetic studies indicate that Neolithic migrants who spread agricultural practices and their genes across Anatolia and into Europe originated in the Levant, primarily utilizing maritime routes for their dispersal. Genetic clustering observed between Neolithic Cypriots and Neolithic Anatolians, further suggests a likely migration by sea.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Southeastern Mediterranean

The southeastern Mediterranean covers the coast of Egypt from the Sinai to west of the Nile Delta.

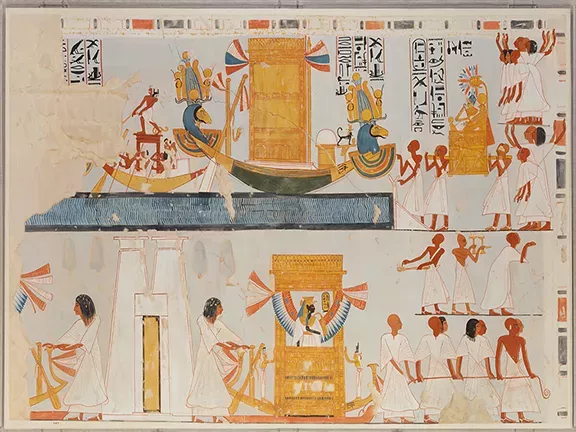

Why Did Egypt Lag Behind in Neolithic Maritime Development?

The Neolithic practices developed in the Fertile Crescent, were late arriving in Egypt. They arrived in about 6500 BC by land, rather than by sea. Mesolithic mariners in the southeastern Mediterranean had no part to play. In fact, Egypt ignored the sea, that they called, 'The Great Green', until about 3500 BC, concentrating their trade routes along the 'Ways of Horus' via which they exchanged goods with the emerging civilisations in the Middle East. Copper, oils and wines entered Egypt from the Levant, whilst copper and turquoise came in from Sinai. Gold from Nubia and grain from the Nile Delta were the main exports.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Aegean Sea: Island Hopping and Maritime Trade

Obsidian network from Melos

The colonisation of the Aegean Sea was accomplished by 'island hopping'

How Did Neolithic People Colonize the Aegean Islands?

The Neolithic reached the Aegean Sea between 7000 and 6500 BC. Most of the major islands in the Aegean had been colonised by about 3200 BC and the smaller by 2600 BC. We now see, for the first time, a depiction of the type of boats that were being used in the Aegean. Two types of boat are shown on rock carvings and on pottery, small canoes and elegant long boats. A rock carving at Naxos shows an animal being loaded onto a boat and three lead models of long boats were recovered from a tomb dating to between 2500 and 2000 BC. The long boats were apparently 15 to 20 metres long propelled by a couple of dozen rowers. They had a raised stem and stern post surmounted by an emblem of a fish.

The "island-hopping" theory: Anatolia to Greece via the Aegean

The prevailing theory suggests that this transformative period, characterized by the adoption of agriculture and settled life, spread into Europe primarily through a process of "island-hopping" from Anatolia across the Aegean Sea to mainland Greece. This initial dispersal led to the establishment of the earliest Neolithic settlements in various parts of Greece, including the fertile plains of Thessaly, the Peloponnese, and notably on the island of Crete at Knossos.

The continued trade of Melian obsidian in the Early Neolithic Aegean

The trade in Melian obsidian, which was already evident in the Mesolithic period, continued to be a significant feature of the Early Neolithic across the Aegean. Melian obsidian artifacts have been discovered at numerous Early Neolithic sites not only on mainland Greece and the Aegean islands but also extending to the western coast of Anatolia, including the Izmir region and as far north as Coskuntepe.

The spread of fired pottery technology across the Aegean

Around 6500 BC, the technology of producing fired pottery emerged and began to spread across the Aegean region. Similarities observed in the styles of these early pottery vessels, such as simple hemispherical bowls and red burnished ware, found at different sites across the Aegean, might suggest a degree of contact and exchange of ideas or even the movement of the pottery itself between communities.

The appearance of impressed pottery: Connections with the Levant and Northern Syria

Notably, a specific type of pottery characterized by impressed decorations appeared around 6100-6000 BC simultaneously on both the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean sides, indicating connections with the Levant and Northern Syria. The near-simultaneous appearance of this impressed pottery across a wide geographical area strongly implies the existence of maritime routes that facilitated cultural exchange and contact between these regions.

The submerged settlement at Aghios Petros: Evidence of Early Neolithic maritime activity

Further direct archaeological evidence for Early Neolithic maritime activity comes from the discovery of the submerged settlement at Aghios Petros, located off the coast of Kyra Panagia Island in the Northern Sporades. This Stone Age settlement has been dated to approximately the second half of the 7th millennium BC, around 6500 BC. Excavations at this underwater site have revealed the remains of stone houses and a community that consisted of farmers, fisherfolk, and seafarers, who left behind a rich deposit of artifacts, including painted pottery and tools made from flint.

Integration of agriculture and marine resource exploitation in Neolithic Aegean communities

The existence of such a settlement on an island clearly demonstrates that Early Neolithic communities were not only capable of reaching and inhabiting islands but also developed a mixed economy that integrated both terrestrial agriculture and marine resource exploitation, further underscoring their seafaring abilities.

Continued distribution of Melian obsidian and new obsidian sources

During the Middle Neolithic period, about 6000 to 5500 BC, the distribution of Melian obsidian continued to be a prominent feature across the Aegean. Archaeological investigations have revealed evidence for the exploitation of both the Demenegaki and Sta Nychia sources on the island of Melos, indicating sustained access to these primary sources. Furthermore, there is emerging evidence for the appearance of obsidian originating from other sources, such as Anatolia and the island of Giali in the Dodecanese.

Population expansion and the establishment of new settlements in the Aegean

The Middle Neolithic period also saw a notable expansion in population and the establishment of new settlements across the Aegean, including the colonization of more islands.

Coastal settlements and defensive structures in the Middle Neolithic Aegean

Archaeological evidence reveals the presence of coastal settlements, such as Makriyalos in Macedonia, and at Nea Nikomedeia, which were surrounded by defensive ditches.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Adriatic Sea: The Spread of Impressed Ware

Impressed ware pottery is the earliest Neolithic pottery of the Mediterranean area, with decoration impressed into the clay by sticks, combs, fingernails, or seashells

The appearance and spread of Impressed Ware pottery in the Adriatic

Within the Adriatic region, the Early Neolithic is generally recognized as beginning around 6000 BC with the appearance and spread of Impressed Ware pottery. Archaeological sites featuring Impressed Ware pottery are widely distributed along the eastern Adriatic coast and islands, with dates ranging from approximately 6500 to 5500 BC. This cultural phenomenon is not limited to the Adriatic; Impressed Ware is also found throughout the western Mediterranean and even beyond and we saw above that Impressed Ware appeared in the Aegean about 6100 BC.

Impressed Ware site of Crno Vrilo

Excavations at the Impressed Ware site of Crno Vrilo in Dalmatia, Croatia, have unearthed lithic artifacts made from high-quality cherts that originated in the Gargano region of southern Italy.

Evidence of Neolithic elements on Adriatic islands: Impressed Ware and domesticated animals

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the seafaring capabilities associated with the Impressed Ware culture is the early appearance of Neolithic elements, including Impressed Ware pottery and domesticated animals, on various Adriatic islands including Corfu, Susac and islands in the Kvarner archipelago. Archaeological evidence indicates that these first traces of the Neolithic on the East Adriatic islands date to approximately 6000 BC.

The emergence of the Danilo culture and its distinctive pottery styles

Another important cultural entity in the Adriatic Neolithic is the Danilo culture, which emerged around the mid-fifth millennium BC and is known for its distinctive pottery styles.

The arrival and subsequent dissemination of Impressed Ware culture across the Adriatic and into the wider Mediterranean basin strongly suggests a significant stage in the development of seafaring. The widespread distribution of this relatively uniform cultural element implies a mechanism for its dispersal, with maritime travel being the most plausible explanation.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Tyrrhenian Sea: Obsidian Trade and Maritime Networks

The Ligurian Sea is an arm of the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies between the Italian Riviera (Liguria) and the island of Corsica.

What Evidence Exists for Neolithic Maritime Links in the Ligurian Sea?

A rare find of an axe manufactured in the southwest Alps, found in southern Corsica, proves a maritime connection across the Ligurian Sea sometime between 5500 and 4900 BC.

Sardinian Obsidian Trade: How Was Sardinian Obsidian Distributed Across the Tyrrhenian Sea?

The obsidian from its source at Monte Arci on the western side of Sardinia was distributed to Corsica, the coasts of central and northern Italy and north to Liguria and southern France from at least the early Neolithic period, about 5000 BC and probably much earlier, during the Mesolithic period.

Pantelleria Obsidian: What Role Did Pantelleria Play in Neolithic Maritime Trade?

Midway between Sicily and Tunisia is the tiny island of Pantelleria. Too small to support a Mesolithic or Neolithic population, the obsidian resources were repeatedly visited from the early Neolithic period.

Pantelleria as a stepping stone for Neolithic colonization: Tunisia

It is likely that Neolithic colonisers used Pantelleria as a stepping stone to reach the coast of Tunisia about 60 kilometres away. Only one settlement site is known on the island. Mursia was established during the bronze age. The iconic Sesi, megalithic multi-burial structures, were also built during this period.

DNA studies: Tracing the origins of Pantelleria's first population

From DNA studies, it transpires that the first population on the island did not originate on Sicily as may be expected, but from the Iberian Peninsula or possibly Liguria.

Maritime Networks from Sardinia: How Did Sardinia Influence Neolithic Maritime Trade?

Sardinia, strategically positioned in the centre of the western Mediterranean, played a pivotal role in the circulation of resources and the development of maritime networks during both the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Archaeological evidence reveals a complex picture of trade, exchange, and social interaction, highlighting Sardinia's significance in shaping the cultural and economic landscape of prehistoric Europe.

Neolithic Obsidian: Early Maritime Routes and Social Networks

During the Neolithic period, Sardinian obsidian, a highly valued volcanic glass, became a crucial commodity, circulating through various routes and mechanisms. Traditional theories suggested a "down-the-line" exchange, with obsidian moving through the Tuscan Archipelago, utilizing islands like Elba and Pianosa as stepping stones to northern Italy and France. However, social network analysis (SNA) has unveiled a more direct open-sea route, particularly during the fifth millennium BC, where obsidian travelled from Corsica to Provence and Languedoc, a journey of over 200 kilometres.

Social network analysis of Sardinian obsidian distribution

SNA, employing Brainerd-Robinson coefficients to measure similarities in obsidian assemblages, reveals clusters of sites with frequent interaction, highlighting the interconnectedness of these communities. Obsidian comes in two chemical types, known as SA and SC. The type of obsidian also influenced its distribution. SC obsidian was primarily for local use, while SA obsidian was meticulously prepared for export to Corsica and the mainland.

The role of obsidian in social distinction and power: Gateway communities

Sites like Terres Longues in southern France likely served as redistribution centres, integrated into existing flint exchange networks. The accumulation of obsidian at specific locations suggests its role transcended mere utility, serving as a means of social distinction and power. Control over production techniques, particularly pressure-flaked blades, likely contributed to the institutionalization of power, with certain sites acting as "gateway communities" or "central nodes" in obsidian redistribution.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Central Mediterranean: Malta and Gozo

Malta and Gozo are two small islands that lie south of Sicily, part way between Sicily and Tunisia.

Early Neolithic settlers on Malta and Gozo: Cave dwellings

About 100 kilometres south of Sicily are the islands of Malta and Gozo. Recent archaeological discoveries at Latnija, on the northern coast of Malta have unearthed a Mesolithic presence that lasted until about 5500 BC. The island apparently remained uninhabited until the end of the sixth millennium when Neolithic settlers arrived from Sicily and Africa. They lived in caves and rock shelters.

Maritime contact between Sicily, Malta, and Gozo: Stone axes and obsidian

Contact between Sicily, Malta and Gozo, as indicated by finds of stone axes and obsidian, were maintained until about 4800 BC, when the islands were deserted. This was probably for two reasons, a change in the climate resulted in less rainfall, and the available agricultural land had been degraded to such an extent that it could no longer sustain useful crops. There is some evidence, through pottery designs, that contact was maintained with other cultures.

Neolithic Temple Builders: Who Built the Megalithic Temples of Malta?

Malta and Gozo would remain unoccupied until about 3850 BC when Neolithic settlers arrived from Sicily. These people started building the unique Temples about 3800 BC. Once again, the climate intervened and the islands again became severely depopulated, if not entirely abandoned, about 2350 BC.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Western Mediterranean: Coastal Navigation

Obsidian is a volcanic glass prized for its ability to form a razor sharp edge when knapped and for its glossy appearance. It is found in shades of green to black.

Obsidian trade between Tyrrhenian islands and the French coast

On the northern shores of the Ligurian Sea, at Peiro Signado (southern France) and Pont de Roque-Haute in the Portiragnes area, obsidian described only as Tyrrhenian in the former case and specifically from the island of Palmarola in the latter case, are dated to levels equating to between 5800 and 5600 BC, pretty much on the Mesolithic/Neolithic divide for that region but nevertheless showing a definite communication by sea.

The ceramic production at Peiro Signado shows similarities with series from the Arene Candide cave (Liguria), indicating a Ligurian "bridgehead" towards the west similarly, the ceramics from Pont de Roque-Haute resembles that from Giglio Island in the Tuscan archipelago.

The rapid spread of the Neolithic "package": Coast-hopping ventures

The only evidence, and that is circumstantial, of extensive coastal navigation in the western Mediterranean, occurs during the 6th millennium BC, when the Neolithic 'package' arrived in northern Italy, southern France and the Iberian Peninsula. Within only 300 years, Neolithic practices, together with the associated livestock and agricultural products had reached the Atlantic shores of Portugal. It is strongly suspected that the rapid spread of the Neolithic was helped by a series of coast hopping ventures in vessels like the Lake Bracciano canoes described in the previous article, 'Mesolithic Sea Routes in the Mediterranean'.

If that is the case, then the knowledge of coastal navigation gained by their Mesolithic predecessors would have been invaluable.

The arrival of the Neolithic package in the Iberian Peninsula coincided with a change in the climate recorded as the 8200 BP event. Temperatures dropped and aridity increased. The Mesolithic population tended to move to estuarine locations leaving unoccupied gaps in the landscape. The earliest Neolithic settlements in Iberia appeared in coastal areas without any significant evidence of previous Late Mesolithic occupations. This indicates that the first Neolithic settlements followed a strategy of non-overlapping with local forager populations.

Where are the first signs of the Neolithic in Spain?

The earliest farming data is linked to coastal or neighbouring coastal areas on the Mediterranean coast of Spain (Central Catalonia, South Valencia and Malaga) and Portugal (the Algarve and North Estremadura). There is little to no evidence of previous Late Mesolithic occupations in those areas.

This suggests that expansion occurred by sea, resulting in long-distance relocation episodes to early Neolithic enclaves. This might explain the observed gaps in occupation and the speed of the Neolithic expansion.

Can Sadurni Cave (Catalonia, Spain), provided dates on cereal (5470 to 5300 BC), although the sample is a cluster of charred cereals retrieved from the same ceramic ware.

Moving south, the open-air site of Mas d'Is (Valencia, Spain), is now the area with the oldest radiocarbon dates on cereals. It dates to 5600 to 5500 BC.

The El Barranquet (Valencia, Spain) site has yielded an old radiocarbon date in sheep bone. One ceramic context is dominated by impressed non-Cardial ceramics very similar to the Ligurian phases of Sillon d'Impressions documented in southern France. It has been suggested that this ceramic impressed horizon could even be pre-cardial, representing the first Neolithic cultural complex in Iberia before 5500 BC.

Close on Valencia's heels and south again, is Nerja Cave (Andalucia, Spain). This site contained one of the oldest sheep bone samples, dating to c. 5600 to 5400 BC. However, the archaeological context of the sample was disturbed. The researchers of Los Castillejos (Andalucia, Spain), suggest that the development of this site would correspond to an advanced Early Neolithic, between 5500 and 5000 BC, progressing into a very short Neolithic period between 5000 and 4900 BC.

When did the Neolithic expansion period end in the Iberian Peninsula?

Within a few years, the Neolithic met the westernmost parts of Europe, in Atlantic Portugal. In the Algarve region at Cabranosa and Padrão, radiocarbon determinations from these early Neolithic sites are based on shell samples. They date to 5600 to 5500 BC. Whilst in Northern Estremadura in Almonda and Caldeirao caves, dates from short-lived materials such as adornments, and sheep and human bones, have been found dating to 5400 BC and 5300 BC, respectively.

Balearic Island Colonization: When were the Balearic Islands First Colonized?

The Balearic Islands are only visible from mainland Spain under certain atmospheric conditions. When the air is absolutely clear of cloud then the highest peaks of the Serra de Tramuntana mountains on Mallorca are visible at sunset from the Fabra observatory above Barcelona. They are 206 kilometres away. The much lower island of Ibiza, although closer to the mainland at 147 kilometres, is not visible from Spain.

All the evidence to date suggests that the Balearic Islands were not visited or inhabited until after the Neolithic expansion into the Iberian Peninsula.

Early theories on the colonization of the Balearic Islands.

For a long time, the generally accepted view was that the Balearic Islands were first colonized in the 3rd millennium BC, during the Early Bronze Age. This was based on evidence from sites with megalithic structures (like dolmens) and pottery styles that linked the islands to cultures in the Eastern Pyrenees and Languedoc regions of mainland Europe.

Recent discoveries: A submerged stone bridge in the Genovesa Cave, Mallorca.

A recent study, published in 2024, has significantly pushed back the date of human arrival on Mallorca. Researchers discovered a submerged stone bridge in the Genovesa Cave in Manacor. By using radiometric dating techniques, they determined that the bridge was constructed at least 5,600 years ago.

Revised dating of human presence on Mallorca: 4th millennium BC.

This suggests that humans were present on Mallorca at least 1,000 years earlier than previously thought, around the 4th millennium BC.

Neolithic Connections to North Africa

Whether or not there were significant routes during the Neolithic period from the Iberian Peninsula to North Africa or via Sicily, from the Italian Peninsula to North Africa, or, indeed vice versa, has long been subject to heated debate.

The Alboran Sea connection: Did Neolithic people cross the Alboran Sea?

The Alboran Sea, a relatively narrow strait separating the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa, appears to have functioned as a crucial conduit for the spread of Neolithic practices. The Early Neolithic site of Nerja, with its remarkably early dates (5603?5490 BC), is potential indication of this maritime connection. Its interpretation as a pioneer site resulting from a rapid, sea-borne expansion from North Africa aligns with a "maritime pioneers colonisation model." The observed hiatus in Mesolithic occupation at Nerja, coupled with the early Neolithic levels, further reinforces the hypothesis of an arrival by sea from the Maghreb.

Several lines of evidence support this hypothesis:

Early Domesticates: The simultaneous introduction of the first domestic plants along the coasts of Morocco and Andalusia in the mid-sixth millennium cal. BC suggests a shared origin or rapid transmission of agricultural knowledge.

Material Culture: The homogeneous stone implements, and personal ornaments found in the Early Neolithic of Andalucia exhibit striking similarities to those found in the Maghreb.

Ceramic Connections: Recent research has clarified the chronological and cultural relationship between Andalucia and North Africa during the 6th millennium BC. Specifically, the ceramic record of Cabecicos Negros shows closer ties to the eastern Rif mountains in Morocco.

Lithic Technology: Technological and functional studies of lithic sickles have identified relationships between those found in Andalucia, Portugal, and northern Morocco, indicating shared technological traditions.

While the systematic use of red ochre in Andalucian Early Neolithic ceramics is a distinctive feature, and ochre was used in the corresponding Capsian period in the Maghreb, it is recognized that this factor alone cannot definitively prove a direct North African origin.

The emerging picture of the Early Neolithic in the Western Mediterranean reveals a significant role for maritime connections, particularly between the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. The Alboran Sea appears to have facilitated the rapid spread of Neolithic practices, including agriculture, technology, and material culture.

Bridging Continents by Sea: Maritime Connections Between the Iberian Peninsula and Morocco During the Neolithic Period

The close geographical proximity between the Iberian Peninsula and the northwestern coast of Africa, separated by the Strait of Gibraltar, has facilitated interactions across various historical periods. We focus here on the maritime connections between the Iberian Peninsula and three specific regions within Morocco, Oued Beht, the Gharb Lowlands, and Mzoura, during the Neolithic period, roughly spanning from the Late Stone Age to the Copper Age (c. 3400 to 2900 BC).

Early Encounters: Neolithic Maritime Hints and Oued Beht

Archaeological investigations at Oued Beht in Morocco have revealed a significant farming society that flourished between approximately 3400 and 2900 BC. This site represents the earliest and largest agricultural complex discovered in Africa outside the Nile Valley, indicating a sophisticated level of societal organization and agricultural practices during the Late Neolithic. Evidence includes domesticated plants and animals, pottery, and extensive storage pits, suggesting a departure from the previously assumed dominance of nomadic pastoralism in the region.

The findings at Oued Beht exhibit notable similarities with contemporaneous archaeological sites in the Iberian Peninsula. The presence of dark-on-light painted pottery at Oued Beht, a style also found in southern Iberia, further supports these connections. Striking technological parallels exist between the storage pits at Oued Beht and the silos characteristic of the 'silo culture' that extended from Portugal to western Andalucia. Faunal analysis also indicates similarities in the animal species husbanded in both regions during this period, suggesting early Neolithic connections. The exchange of material culture is further evidenced by the discovery of ostrich eggs and African ivory in Iberian sites such as Valencina de la Concepción and Los Millares. Genetic studies have also revealed evidence of two-way movements of people between the Iberian Peninsula and northwest Africa during the Late Neolithic, predating later historical connections. These multiple lines of evidence strongly suggest significant interaction between the community at Oued Beht and the Iberian Peninsula during the Late Neolithic, implying some form of maritime or coastal contact across the Strait of Gibraltar. It is even theorized that the technology of storage pits may have been transferred from south to north, from Oued Beht to Iberia.

While Oued Beht is currently located approximately 100 kilometres inland, it is theorized that the geography of the region was different during the Late Neolithic. The Gharb drainage system to the north of the site may have formed a more pronounced indented embayment or estuarine wetland, potentially bringing maritime access closer to Oued Beht or shortening the overland distance to coastal communities with maritime links to Iberia.

The Gharb Lowlands and the Sebou River in the Neolithic

The Gharb Lowlands, a coastal plain in northwestern Morocco, are traversed by the Sebou River. While the Sebou River was noted for its navigability in antiquity, evidence for its use as a significant maritime route during the Neolithic period specifically for connections with the Iberian Peninsula is less direct. However, the presence of a substantial agricultural society at nearby Oued Beht suggests that the fertile Gharb Lowlands likely supported other settlements during this era. The potential for a more indented coastline in the Gharb region during the Neolithic could have facilitated coastal navigation and interaction, indirectly linking the Gharb Lowlands to the maritime exchanges occurring across the Strait of Gibraltar. The movement of people and goods between Oued Beht and the coast would have been crucial for any maritime connections with Iberia.

Mzoura: A Megalithic Monument with Possible Neolithic Connections

Mzoura, a stone circle located about 60 kilometres south of Tangier, near the Atlantic coast of Morocco, was originally estimated to date back to the 4th or 3rd century BC. However, surveys have suggested potential connections between Mzoura and earlier megalithic structures in Europe, some dating to the Neolithic period, in particular the megalithic societies on the Iberian Peninsula that date back to the mid-5th millennium BC. Similarities in construction techniques, such as the use of a Pythagorean right-angled triangle, and potential astronomical alignments with solstices and equinoxes, features common in Neolithic European megaliths, hint at cultural connections across the Atlantic seaways during prehistory. While primarily interpreted as a burial site from the Iron Age, the possibility of earlier Neolithic phases or connections to broader megalithic networks with maritime links cannot be entirely excluded.

What did a Neolithic colonising voyage look like?

We can only guess as to the size of a colonising voyage from assumptions.

The minimum size of a self-sustaining population consists of about forty individuals. They would have to take with them something like ten to twenty pigs, cattle, sheep and/or goats, and a supply of seed grain, together with enough water and food to sustain them on their voyage. The total minimum cargo would have been between 15,000 and 20,000 kilogrammes. If we assume each boat could carry between 1 and 2 tonnes, somewhat larger than the Lake Bracciano canoes, that implies a flotilla of between ten and twenty vessels.

Conclusion: The emerging maritime networks in the Mediterranean

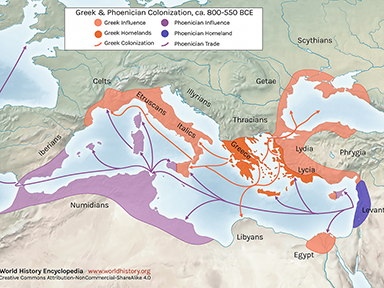

The 'local', short distance, maritime routes established during the Mesolithic period that were primarily used for obtaining rare resources such as obsidian, became more connected as a Neolithic wave swept from the eastern Mediterranean to the west.

A network evolved between the Levant or southern Anatolia and Cyprus, tentatively linked to the southern Aegean. Connections were made across the Aegean Sea between Anatolia and Greece and as far south as Crete, and across the Adriatic between Greece and Italy, effectively all points east of the eastern shores of Italy.

Around the toe of Italy, Sicily appears as a Neolithic hub between, potentially, Gozo, Malta and Tunisia. There is yet only circumstantial evidence to prove a direct link across the Ionian Sea between southern Italy and the well-travelled eastern Mediterranean zone.

The Tyrrhenian Sea bounded to the east by mainland Italy, the north by Liguria, and west by Sardinia is clearly well travelled.

West of Sardinia, to the Gibraltar Straits, is a fourth, less coherent zone, where we can barely perceive an emerging network, until we reach the far west where slightly better clarity allows us to observe a link between the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa.

So, by about 5500 BC, there are four marine exchange zones, the eastern Mediterranean, the central Mediterranean, the Tyrrhenian Sea, and the western Mediterranean, each buzzing about its own business but only peripherally aware of each other.

The increasingly complex web of routes that emerged during the Neolithic advance can be identified by manufactured goods, such as ceramics, and by livestock and edible plants, carried from A to B. Alongside the cargoes, technological ideas and innovations spread selectively between communities. Finally, DNA research indicates that people were also on the move, to previously uninhabited islands and mixing with pre-existing hunter gatherer populations.

References

Neolithic Revolution at Sea

Garcia-Escarzaga, A.; Cantillo, J.J.; Milano, S.; Arniz-Mateos, R.; Gutierrez-Zugasti, I.; Gonzalez-Ortegon, E.; Corona, J.M.; Colonese, A.C.; Ramos-Munoz, J.; Vijande-Vila, E. 2024. Marine resource exploitation and human settlement patterns during the Neolithic in SW Europe: Stable oxygen isotope analyses (?18O) on Phorcus lineatus (da Costa, 1778) from Campo de Hockey (Cadiz, Spain), Archaeological and Anthropological Science. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-01939-0

Neolithic Seafaring in the Eastern Mediterranean

Manning, Sturt & Mccartney, Carole & Kromer, Bernd & Stewart, Sarah. (2015). The earlier Neolithic in Cyprus: Recognition and dating of a Pre-Pottery Neolithic A occupation. Antiquity. 84. 693-706. 10.1017/S0003598X00100171.

Simmons, Alan. (2012). Ais Giorkis : An unusual early Ne olithic settlement in Cyprus. Journal of Field Archaeology. 37. 86-103. 10.1179/0093469012Z.0000000009.

Mark, Joshua J. "Trade in Ancient Egypt." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 15 Jun 2017. Web. 25 Feb 2025.

Bunson, M. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Gramercy Books, 1991.

Lewis, J. E. The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Ancient Egypt. Running Press, 2003.

Silverman, D. P. Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 1997.

The Egyptian Economy by James C. Thompson, accessed 15 Jun 2017.

Van De Mieroop, M. A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Wilkinson, T. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Aegean Sea

Adamantios Sampson, J. K. Kozlowski, M. Kaczanowska, (2016) Lithic Industries Of The Aegean Upper Mesolithic: Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 16 No 3,(2016), pp. 229-243

Ammerman, Albert & Efstratiou, Nikos & Ntinou, Maria & Pavlopoulos, Kosmas & Gabrielli, Roberto & Thomas, Kenneth D & Mannino, Marcello A. (2008). Finding the early Neolithic in Aegean Thrace: The use of cores. Antiquity. 82. 139-150. 10.1017/S0003598X00096502.

Birch, Suzanne. (2017). From the Aegean to the Adriatic: Exploring the Earliest Neolithic Island Fauna. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 13. 1-13. 10.1080/15564894.2017.1310774.

Cilingiroglu, Ciler. (2010). The appearance of impressed pottery in the Neolithic Aegean and its implications for maritime networks in the Eastern Mediterranean. TUBA-AR. 13. 9-22.

Liritzis Maxwell, Veronica. (2007). Seafaring, craft and cultural contact in the Aegean during the 3rd millennium BC. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 17. 237 - 256. 10.1111/j.1095-9270.1988.tb00651.x.

Reingruber, Agathe. (2011). Early Neolithic settlement patterns and exchange networks in the Aegean. Documenta Praehistorica. 38. 291. 10.4312/dp.38.23.

Sahoglu, Vassf. (2005). Interregional Contacts Around the Aegean During The Early Bronze Age: New Evidence from the Izmir Region. Anadolu (Anatolia). 27. 10.1501/Andl_0000000310.

Sampson, Adamantios. (2015) An Extended Mesolithic Settlement In Naxos: Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 16, No 1 (2016), pp. 269-271

Strasser, Thomas & Panagopoulou, Eleni & Runnels, Curtis & Murray, Priscilla & Thompson, Nicholas & Karkanas, Panagiotis & Fw, Mccoy & Wegmann, Karl. (2010). Stone Age Seafaring in the Mediterranean: Evidence from the Plakias Region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Habitation of Crete. Hesperia. 79. 145-190. 10.2972/hesp.79.2.145.

Tomkins, Peter & Day, Peter. (2015). Production and Exchange of the Earliest Ceramic Vessels in the Aegean: A View from Early Neolithic Knossos, Crete. Antiquity. 75. 259-260. 10.1017/S0003598X0006083X.

Tsampiri, Mailinta. (2018). Obsidian in the prehistoric Aegean: Trade and uses. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece. 53. 28. 10.12681/bgsg.18588.

Veropoulidou, Rena. (2021). The shell artefact assemblage at Neolithic Catalhoyuk.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Adriatic Sea

Kacar, Sonja. (2021). The Neolithisation of the Adriatic: Contrasting Regional Patterns and Interactions Along and Across the Shores. Open Archaeology. 7. 798-814. 10.1515/opar-2020-0166.

Kaiser, Timothy & Forenbaher, Stano. (2015). Navigating the Neolithic Adriatic.

Radi, Giovanna & Petrinelli Pannocchia, Cristiana. (2017). The beginning of the Neolithic era in Central Italy. Quaternary International. 470. 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.06.063.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Tyrrhenian Sea

Freund, Kyle & Batist, Zack. (2014). Sardinian Obsidian Circulation and Early Maritime Navigation in the Neolithic as Shown Through Social Network Analysis. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 9. 364-380. 10.1080/15564894.2014.881937.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Central Mediterranean

Bonanno, A. (2005). Malta: Phoenician, Punic, and Roman. Midsea Books.

Evans, J. D. (1971). The Prehistoric Antiquities of the Maltese Islands. Athlone Press.

Malone, C., & Stoddart, S. (2001). Death rituals, social order and the archaeology of the Maltese temples. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 11(1), 41-60.

Robb, J. (2007). The Ancient Mediterranean. Princeton University Press.

Rowan, C., & Bell, M. (2015). Climate change and human response: a geoarchaeological perspective. Journal of Archaeological Science, 53, 211-220.

Eleanor M. L. Scerri et al., Hunter-gatherer sea voyages extended to remotest Mediterranean islands, Nature (Published online: 09/04/2015), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08780-y

Sammut, C. (2011). Prehistoric Malta: A Corpus of Pottery from the Neolithic to the Tarxien Cemetery Phase (c. 5200-2500 BC). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Stoddart, S., Malone, C., & Trump, D. (1993). Cult and culture at the ?gantija temples, Malta. Antiquity, 67(256), 679-687.

Trump, D. H. (2002). Malta: Prehistory and Temples. Midsea Books.

Tykot, R. H. (1996). Obsidian sources and trade in the Mediterranean. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 9(1), 39-82.

Vella, N. C. (2012). The Prehistoric Temples of Malta. Midsea Books.

Rowan, C., & Bell, M. (2015). Climate change and human response: a geoarchaeological perspective. Journal of Archaeological Science, 53, 211-220.

Neolithic Seafaring in the Western Mediterranean

Fernandez Lopez de Pablo, J., & Gomez Puche, M. (2009). Climate change and population dynamics during the Late Mesolithic and the Neolithic transition in Iberia. Documenta Praehistorica, 36

Garcia-Puchol, Oreto & Salazar-Garcia, Domingo. (2017). Times of Neolithic Transition along the Western Mediterranean. 10.1007/978-3-319-52939-4.

Guilaine, J. & Manen, C. (2007). From the Mesolithic to Early Neolithic in the western Mediterranean. In Proceedings of the British Academy (144, 21 - 51). The British Academy 2007. DOI: 10.5871/bacad/9780197264140.003.0003

Martin-Socas, D., Camalich Massieu, M.D., Caro Herrero, J.L., & Rodriguez-Santos, F.J. (2018). The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia. Quaternary International, 470, 451-471

Connections to North Africa

Broodbank, C., Lucarini, G., Bokbot, Y., Benattia, H., Bigoulimen, A., Farr, L., Garcia-Molsosa, A., Hachami, H., Laoutari, R., Lombardi, L. V., Marsilio, M., Martin, L., Morales, J., Radi, S., Rega, E., & Wilkinson, T. (2024). Oued Beht, Morocco: a complex early farming society in north-west Africa and its implications for western Mediterranean interaction during later prehistory.1 Antiquity, 98(397), 1-201.

Lipson, M., Ringbauer, H., Lucarini, G. et al. (2025). High continuity of forager ancestry in the Neolithic period of the eastern Maghreb. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08699-4

Lucarini, G., Bokbot, Y., & Broodbank, C. (2021). The prehistoric site of Oued Beht (Khimisset, Morocco): an interpretative report on 2021 - 2022 fieldwork and associated research. Libyan Studies, 52, 1 - 30.

Ancient Origins. (n.d.). Mzora Stone Circle: An Enigmatic Megalithic Monument in Morocco

Tarradell, M. (1959). Art rupestre del Marroc. Institut d'Estudis Catalans.

Raissouni, N., Casasola, J., Khayari, A., Munoz, D., & Zouak, M. (2016). The Late Stone Age in the Maghreb: An overview. Quaternary International, 391, 45-57

Daugas, J. P., Maggiani, R., & Nami, H. G. (2012). Megalithismes de l'Europe atlantique et au-del: actes du colloque international de Saint-Nazaire, 6-10 octobre 2008. Association Archeologique de l'Ouest et du Centre de la France

Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia

Ruhlmann, A. (1936). Le site prehistorique d'Oued Beht. Bulletin de la Society Prehistorique Francaise, 33(10-12), 548-553

Hilmi, M., Mahamoud, Y. A., Aziz el Agbani, M., & Qninba, A. (2022). Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Strategies in the Sebou River Basin, Morocco. Springer Nature

Plutarch. Parallel Lives1

Brooke, A. de C. (1831). Sketches in Spain and Morocco. H. Colburn and R. Bentley

Bleicher, G. M. (1875). Le tumulus de Mzora (Maroc). Bulletin de la Society d'Anthropologie de Paris, 8(1), 136-143

Koehler, H. (1932). Le cromlech de Mzora. Hesperis, 14(1-2), 1-24

Montalban, C. L. de. (1935). Exploraciones arqueologicas en la region de Arcila

Tarradell, M. (1958). Marruecos punico. Instituto de Estudios Africanos

Camps, G. (1962). Aux origines de la Berbarie: monuments et rites funaraires protohistoriques. Arts et Metiers Graphiques

Camps, G. (1995). Prehistoire d'une le: le peuplement de la Corse. Errance

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution