Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

Mesolithic Voyages in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mesolithic communities around the Mediterranean Sea were the first to explore their coasts and offshore islands. They gained a knowledge of the seas in their immediate environment, a knowledge that would be used by the Neolithic people who would go on to compound and extend that knowledge further afield. This is the story of those first forays into the ocean by the Mesolithic seafarers.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-03-17 | Last Updated 2025-05-17 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 3,380 times

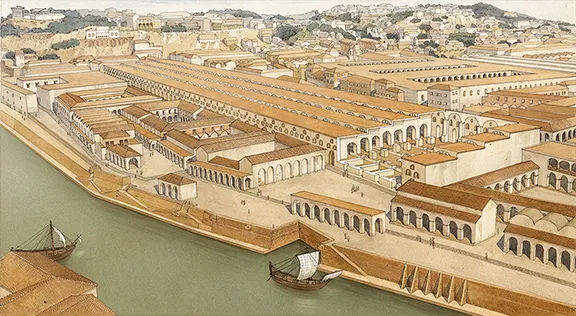

Mesolithic sea voyages. Image Credit: Sheila Terry/Science Photo Library

Who made the first sea journeys in the Mediterranean?

The ancient maritime trade routes in the Mediterranean Sea developed over a period of at least nine thousand years. The first people to venture onto the waters of the Mare Nostrum probably did so during the Palaeolithic period and could have been Homo heidelbergensis or Neanderthals. There are finds on some of the Aegean Islands, and on Crete and Sicily that are contentious at the moment. As far as we know the first people to make repeated return voyages were the Mesolithic people that lived around the edge of the Mediterranean Basin.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

What did the first Mesolithic Voyages look like?

Since no remains of any boats dating to the early part of the Mesolithic have been discovered we have to surmise that they were either fire hollowed dugout canoes, reed boats or skin and frame construction, all feasible with the technology of the time. An experimental voyage in a modern six metre long, reed-built canoe with six paddlers, averaging about 12 kilometres per day with stop overs for bad weather, took two weeks to island hop from Attica, via Kea, Kythnos, and Siphnos to Melos. Allowing a few days to gather obsidian and a return journey of similar duration, the Mesolithic explorers plying this route must have been away from home for at least a month.

It is unlikely that any of the voyages during the Mesolithic would have been made by a single craft, there is safety, and reassurance, in numbers. It is more likely that three or four boats accompanied each other on well-planned expeditions. One can imagine the ceremony on a beach as these, probably male, intrepid explorers departed and a similar, joyous occasion, when they arrived safely home with their precious cargo.

What was the first open sea maritime route in the Mediterranean?

Several Mediterranean islands including Cyprus and islands in the Aegean Sea, were settled or at least visited during the Mesolithic period, thereby establishing the first connections across the seas. The first of these routes would have been journeys from the mainland to a visible destination by small parties of hunter gatherers on foraging expeditions, or even as a diversionary activity whilst fishing. Over time any island in sight of the mainland or offshore fishing canoe, and any island in sight of other islands would have been visited and any resources on those islands were committed to memory, along with knowledge of the currents and landmarks along the route. Not surprisingly, the island studded Aegean was a hotbed of early maritime adventures.

To date, Mesolithic activity on Cyprus is the earliest evidence of an open sea maritime route between the mainland, in this case either southern Anatolia or the Levantine coast, about 65 and 100 kilometres away across open seas, and a Mediterranean island. The mountains in Cyprus are visible from the Turkish mainland.

Recent discoveries (2019) on Malta indicate that Mesolithic hunter gatherers travelled the 100 kilometres from Sicily around 6500 BC. To date this is the first open sea, out of sight of land, voyage in the Mediterranean.

First Sea Voyages in the Eastern Mediterranean

Mesolithic settlers on Cyprus

Archaeological evidence suggests that humans first settled Cyprus around 12,000 to 10,000 years ago, near the end of the Pleistocene epoch and the beginning of the Holocene, coinciding with the Mesolithic period in other regions. This suggests that the first inhabitants were likely hunter-gatherers who may have arrived by sea from the Anatolian or Levantine coasts. These early mariners were hunting a pigmy hippopotamus appropriately named Phanourios minutus whose fully size ancestors had swum over to the island during the Pleistocene.

The significance of Aetokremnos in Mesolithic Cyprus

One of the most significant Mesolithic sites in Cyprus is Aetokremnos, found on the southern coast. This rock shelter has yielded evidence of human activity, including lithic artifacts and the bones of at least 500 dwarf Cypriot hippos and a few pigmy elephants and wild boar. The site is notable for its early date, the 11th millennium BC.

Until the late 20th century AD, there was a deafening silence relating to the period between the early Mesolithic occupation, however transient it may have been, and the arrival of a Neolithic phase some 2500 years later. Recent discoveries are filling in the gap.

A site at Kliminos dated to the early 9th millennium BC, features a roundhouse containing signs that the occupants hunted a wild pig. These animals had been introduced to the island since the Aetokremnos occupation, presumably to augment the wild boar and restock the island with game as the numbers of hippopotami reduced. Here we are apparently seeing a deliberate attempt to manage wild or semi domesticated livestock, reflecting practices on the Levant mainland.

We are also seeing more confident seafaring. Cyprus is two days plus an intervening night away from the nearest land, Turkey, and double that from the Levant, with no island stopovers. A journey moreover that included amongst the passengers, less than willing semi wild pigs. It would make most sense to imagine a separate, towed, canoe for the animals but that is purely hypothetical.

First Sea Voyages in the Southeastern Mediterranean

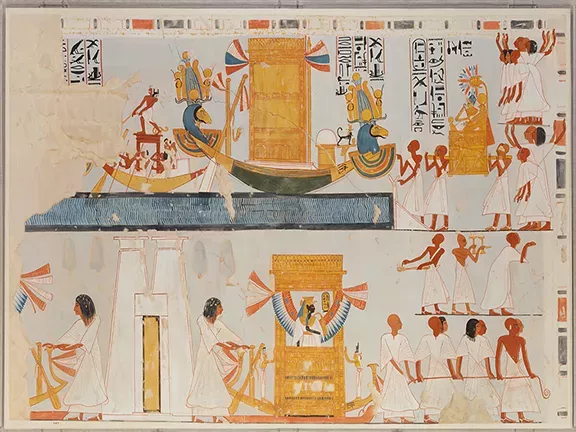

Why was Egypt late to develop Mediterranean seafaring?

Egypt is a special case in that its focus for much of its early history was to the south and east rather than into the Mediterranean. Considering its proximity to the Fertile Crescent, the country was late taking up Neolithic practices, about 6200 BC. It was not until around 3500 BC, well into the Neolithic period, that Egypt started to have an impact on the maritime networks in the Mediterranean, a time when the rest of the Mediterranean was firmly in its Neolithic phase. The impact however was dramatic, for it was Egypt that introduced the sailing ship to the Mediterranean seafarers.

First Sea Voyages in the Aegean Sea

Evidence of Mesolithic seafaring in the Aegean Islands

One of the earliest indications of sea travel in the Aegean involves Mesolithic hunter gatherers paddling their dugout canoes from Franchthi Cave on the Gulf of Argos in the Peloponnese to the island of Melos, about 120 kilometres away. The prize was the obsidian available on Melos. Although the journey could be conducted by island hopping with open sea crossings of no more than about 15 kilometres, this was a significant achievement in 11,000 BC.

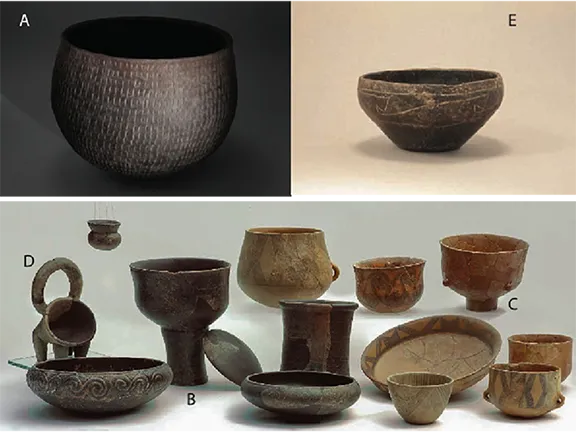

The Aegean's prehistory has been significantly revised in recent decades with the identification of a distinct Mesolithic cultural phase. Previously, this period was primarily documented in scattered locations on the Greek mainland. However, archaeological investigations have progressively revealed a more widespread Aegean presence. Initial evidence appeared with the discovery of the Cyclops Cave site on Youra in the Northern Sporades (1992), followed by extensive excavations at Maroulas on Kythnos (1996-2005). Later work at Kerame on Ikaria (2007-2008) extended the known geographical range of this Mesolithic culture eastward. Surveys in the central and southern Aegean have since uncovered more sites, notably Roos on Naxos and Areta on Chalki.

A consistent characteristic of these Mesolithic sites is their coastal location, suggesting a strong connection to maritime activity and inter-island movement. Obsidian from Melos appears to have been a primary resource, with Yali in the Dodecanese serving as a secondary source. The Roos site on Naxos is particularly noteworthy. Not only does it show typical Mesolithic features, but its substantial size (covering several dozen acres) significantly exceeds that of Maroulas or Kerame. The lithic assemblage at Roos includes obsidian from Melos and flint from the Stelida quarry on Naxos. A recent geo-archaeological survey of Stelida, a chert source and associated stone tool making workshop on Naxos, the largest of the Cycladic islands, has revealed Mesolithic activity dating back to 9000-7000 BC. Artifact typologies show similarities with tools found at Ikaria, Kythnos, Chalki, and the earliest layer X of Knossos (Crete). Certain tool types at Roos may indicate a later Mesolithic phase compared to the sites on Kythnos and Ikaria.

Mesolithic sites in the Dodecanese and Aegean Sea

Archaeological investigations at Areta, on the northern coast of Chalki (Dodecanese), have uncovered a substantial assemblage of Mesolithic lithic artifacts. This discovery marks the first documented Mesolithic settlement in the Dodecanese, expanding the known network of Aegean Mesolithic sites south-eastward and suggesting a potential maritime route connecting the Cyclades and Dodecanese. While Melian obsidian is present, a considerable proportion of the tool assemblage is crafted from the less-than-ideal obsidian of Yali (Nissiros). Concurrent research by the Aegean University has revealed a large Mesolithic site in southern Naxos, conforming to the typical pattern of coastal settlement seen during this period.

Both the Areta and Naxos lithic assemblages share typological similarities with other Aegean Mesolithic sites, such as Maroulas (Kythnos) and Kerame 1 (Ikaria). However, differences in raw material exploitation account for some variations between these assemblages. Although absolute dating is currently unavailable, the prevalence and increasing sophistication of geometric microliths, alongside other microlithic forms, hint at a later phase within the Aegean Mesolithic for both sites. This Upper Mesolithic lithic industry bears resemblance to the aceramic level X of Knossos, suggesting an Aegean origin rather than an eastern Mediterranean influence.

The substantial evidence from the Aegean indicates that the whole of the sea, from the north (Cyclops Cave on the uninhabited island of Youra in the Sporades), to the south (Knossos on Crete) was travelled by the Mesolithic sailor from about 9000 BC and that a route between the islands and mainland to the east (Anatolia) and west (mainland Greece) was well established by 7000 BC.

Mesolithic on Rhodes

What, you may ask, was happening on Rhodes, only 20 kilometres from the Anatolian coast and the most south-eastern of the Dodecanese? While there's growing evidence of Mesolithic occupation in many areas of the Mediterranean, including some of the nearby islands, the evidence for a Mesolithic presence specifically on Rhodes is currently limited and inconclusive. While the possibility of Mesolithic occupation on Rhodes cannot be entirely ruled out, currently, there is no conclusive archaeological evidence to confirm it. Further research is needed to decide whether Rhodes was indeed part of the Aegean Mesolithic maritime network.

Mesolithic occupation of Crete and early seafaring

In 2008 and 2009 AD, surveys on Crete, sponsored by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, further proved a Mesolithic presence on Crete. The surveys also exposed the possibility of an earlier exploration of Crete during the Palaeolithic period.

The Plakias Survey aimed to demonstrate early Holocene (ca. 9000 to 11,000 years ago) coastal resource exploitation in Crete, which was achieved. Additionally, Lower Palaeolithic sites were discovered, suggesting Mediterranean seafaring as early as 130,000 years ago. At the moment the Lower Palaeolithic presence is inconclusive.

The most likely hypothesis, pending further research, is that coastal and estuarine wetland resources in the Plakias region were exploited in both the Pleistocene and early Holocene by two distinct human groups: one in the Middle to Upper Pleistocene (ca. 130,000 b.p. or earlier), and the other in the late Pleistocene - early Holocene (ca. 11,000 to 9000 b.p.).

A minimum of 20 Mesolithic sites, associated with caves and rock shelters, are found between Preveli and Damnoni, with only traces found around Ayios Pavlos. The Mesolithic lithic industry resembles others in Greece. These sites are unexcavated and undated, preventing determination of occupation duration.

The Plakias Mesolithic sites are generally small, possibly logistical camps or extraction sites. Schinaria 1 is a potential repeatedly visited site or residential base. The concentration of sites near coastal wetlands supports the hypothesis of subsistence focused on these areas. Questions remain regarding interior exploration, seasonality, and impact on endemic flora and fauna.

Lower Palaeolithic sites are found between Preveli and Schinaria, associated with marine terraces, paleosols, and debris flow fans. While near caves and rocks shelters, these sites are disturbed, limiting contextual analysis. Upper Pleistocene uplift and marine transgression may have affected preservation.

What is the oldest evidence of sea travel in the Adriatic sea?

The eastern side of the Adriatic Sea comprises the modern Balkan countries of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. The political situation in the area since the end of the First World War has deterred any serious archaeology. It was only during the 21st century that research could resume in the area.

While not as extensively studied as other parts of the Mediterranean, there's growing evidence of Mesolithic presence on islands in the Adriatic Sea. This is hardly surprising since the Adriatic basin is the most indented coastline in the Mediterranean. Off the coast, which is 1,777 kilometres long, there are 1,246 islands of varying sizes, some such as Cres and Krk cover an area of over 400 square kilometres, whilst others are barely uncovered rocks at low tide.

First Sea Voyages in the Tyrrhenian Sea

Earliest short range sea crossings Mediterranean

We start our exploration of the Tyrrhenian Sea, as our forebears did, in the south. At Riparo di Fontana Nuova in southern Sicily, pioneering hunter gatherers who had made the crossing of the Messina Straits about 30,000 years ago, hunted red deer, wild boar, and aurochs. They also found flint 100 kilometres further north at Monte Iudica. Tools found at the site are of the Aurignacian type. These finds are, to date (2025), firm evidence of the earliest sea crossings in the Mediterranean by modern humans. As may be expected, such an early voyage would be modest, in this case only a maximum of 5 kilometres with an island midway across. This early foray into Sicily was not repeated for nearly 20,000 years judging by the lack of subsequent evidence.

Corsardinia

During the last glacial maximum, between 29,000 and 19,000 years ago, sea levels in the Mediterranean were up to 130 metres lower than they are today. The islands of Corsica and Sardina were fused into one, Corsardinia. At the northern end of Corsardinia, the Italian mainland was barely 15 kilometres away. The island was populated by three large mammals, the fast-breeding, hare like Prolagus sardus, a native deer, and a small dog like predator. Excavations at Corbeddu Cave in eastern Sardinia turned up a scrap of human bone associated with cold weather pollen and a pile of deer bones. Upper Palaeolithic tools, found during roadworks on the Campidano plain in southwestern Sardinia provide more confirmation of the Ice Age visitors.

Corsica Sardinia in the Mesolithic

By the early Holocene, Corsica and Sardinia had definitely been isolated from the mainland and each other. The channel between the northern tip of Corsica and the mainland was about 50 kilometres whilst that between the south coast of Corsica and the north coast of Sardinia was about 20 kilometres. There is evidence on both islands, in coastal rock shelters and small caves, of sporadic occupation over a period of about 500 years from between 9000 and 8000 BC. The hunter gatherers were looking for the now extinct Prolagus sardus, a type of rock rabbit that had arrived on the islands hundreds of thousands of years previously. These animals, not seeing human figures as a threat, must have been easy prey. At one cave site there are the remains of over 100,000 of the animals, caught over a period of five hundred years.

The large rabbit was not the only source of meat. There was also species of larger than normal mice and voles. The diet of these early island residents also included great bustards, geese, ducks, monk seals and dolphins (the latter two probably from stranding rather than actively fishing for them).

We can now return to Sicily, where, about 10,000 years ago, people were returning to the island. They made incised images on the walls of Addaura Cave on Monte Pellegrino near Palermo.

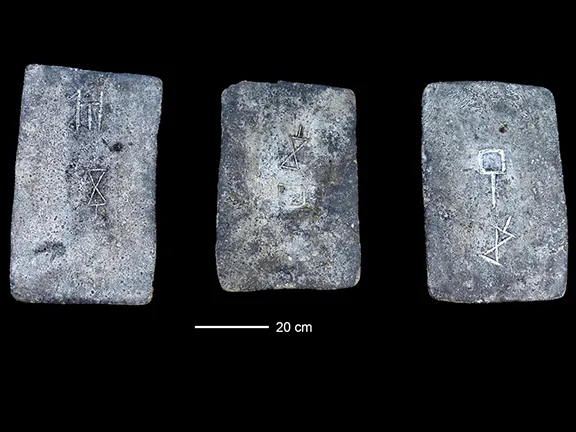

Obsidian in the Tyrrhenian Sea

Volcanic glass or obsidian was a much sought after material during the Mesolithic period for its properties when flaked producing an ultra-hard, razor-sharp edge. We saw above that Mesolithic explorers found obsidian on the island of Melos in the Aegean Sea as early as 11000 BC. In the Tyrrhenian Sea there are four sources of obsidian, Sardinia, Lipari, Pantelleria and Palmarola.

Each is distinctive. That from Lipari, Palmarola and Sardinia are speckled whilst the obsidian from Pantelleria is a distinctive green.

How did obsidian from Sardinia spread?

The obsidian from its source at Monte Arci on the western side of Sardinia was distributed to Corsica, the coasts of central and northern Italy and north to Liguria and southern France from at least the early Neolithic period, about 5000 BC and probably much earlier, during the Mesolithic period.

How old are the Lake Bracciano canoes?

To date, the oldest boats found in the Mediterranean basin date from the late Mesolithic or early Neolithic period. The details of their construction provide us with an insight into the people and the craft that made the early pioneering voyages.

Recent radiocarbon dating of five dugout canoes retrieved from Lake Bracciano, near Rome, places their age between 7,000 and 7,500 years old. This timeframe coincides with the first migration of agricultural communities from the Near East across the Mediterranean and into central Italy. The findings, published in PLOS ONE, establish these vessels as the oldest known Neolithic canoes in Europe.

Where were the Bracciano canoes found?

Discovered at the submerged La Marmotta site, a Neolithic village on the lake's edge, the canoes were remarkably well preserved. The site, rich in archaeological material, includes thousands of structural piles that once supported dwellings, along with remnants of walls, roofs, floors, and hearths. Buried under sediment in an anaerobic environment, the organic materials, including the canoes, were protected from decomposition. Evidence of domesticated animals (primarily sheep and goats, with a few cattle and pigs), canines, and numerous wild animals suggests a mixed economy of herding, hunting, and fishing. Abundant plant remains, encompassing cultivated and wild cereals, legumes, and fruits, were also found. Numerous wooden, basketry, and textile tools, such as spindles, bows, sickles, and adzes, further illustrate the community's activities.

Excavations conducted between 1992 and 2006 unearthed the five canoes, each associated with a dwelling. The boats are notable for their substantial size, with the largest reaching 11 metres in length, and their sophisticated construction. One canoe, for example, features four trapezoidal reinforcements carved into its hull, likely enhancing structural integrity and manoeuvrability. Additionally, three T-shaped mounts with multiple holes were discovered on its side, suggesting the possible attachment of ropes for a stabilizer, or even a second hull to form a catamaran.

What was the purpose of the Lake Bracciano canoes?,

The presence of these canoes at La Marmotta, along with evidence of settlement on various Mediterranean islands during the Mesolithic and early Neolithic, highlights the maritime capabilities of these societies. While other European Mesolithic and Neolithic canoes have been found in association with lakes, suggesting inland navigation, the size of Lake Bracciano raises questions about the intended use of these large vessels. The lake's current size (9.3km across, though smaller in the Neolithic) may not fully account for the need for such large canoes. It is theorized that the canoes may have been used for travel to the Mediterranean Sea via the River Arrone, a distance of approximately 38 kilometres, indicating both lake and sea travel.

The complex design and construction of these canoes provide insights into not only Neolithic seafaring but also social organization. The process of selecting suitable trees, hollowing trunks, and incorporating reinforcements and specialized fittings like the T-shaped mounts suggests specialized knowledge and skills. This level of technical sophistication implies a division of labour within the community, where craftspeople specialized in specific tasks. The construction of the canoes likely required collective effort, overseen by a skilled individual responsible for the entire process, from felling the tree to launching the finished vessel. This suggests a well-structured community with organized labour practices, necessary not only for boat building but also for housing construction, resource procurement, and agricultural activities.

First Sea Voyages in the Central Mediterranean

About 100 kilometres south of Sicily are the islands of Malta and Gozo.

The 2019 discovery of a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer site in Malta, published in Nature in 2025, reveals that humans inhabited this remote Mediterranean island around 8,500 years ago, much earlier than previously thought. Archaeological findings at Latnija demonstrate that these early inhabitants possessed surprisingly advanced long-distance seafaring skills, crossing approximately 100 km from Sicily.

Their diet relied heavily on both marine resources (gastropods, fish, seals) and land animals (red deer), as well as wild plants.

The simple limestone lithic technology found at the site contrasts with contemporary sophisticated tools from Sicily but shows similarities to those from Sardinia.

This evidence challenges existing ideas about the limitations of hunter-gatherer sea travel and suggests earlier and broader connections across the Mediterranean. The Latnija site highlights a unique, sea-dependent lifestyle that differs significantly from later Neolithic agricultural practices in Malta.

First Sea Voyages in the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are only visible from mainland Spain under certain atmospheric conditions. When the air is absolutely clear of cloud then the highest peaks of the Serra de Tramuntana mountains on Mallorca are visible at sunset from the Fabra observatory above Barcelona. They are 206 kilometres away. The much lower island of Ibiza, although closer to the mainland at 147 kilometres, is not visible from Spain.

All the evidence to date suggests that the Balearic Islands were not visited or inhabited until after the Neolithic expansion into the Iberian Peninsula.

First Sea Voyages in the Western Mediterranean

The northern coast of the western Mediterranean, from Liguria to Cadiz, is not blessed with the numerous offshore islands that encouraged the overseas exploration of the Adriatic, Aegean and Tyrrhenian Seas. Parts of the coast, such as that around the Gulf of Lion, the Ebro delta, and the Guadalquivir estuary are low lying marismas. Much of the rest of the coast consists of precipitous cliffs where mountains meet the sea, or a narrow littoral with mountains rising one or two kilometres inland. Along the coast from Liguria to Valencia there are relatively dense concentrations of Mesolithic sites (Lower Ebro and southern Catalonia, Valencia) and zones completely empty of any settlements (Liguria and coastal Catalonia).

Obsidian from Palmarola to southern France

On the northern shores of the Ligurian Sea, at Peiro Signado and Pont de Roque-Haute in the Portiragnes area, obsidian described only as Tyrrhenian in the former case and specifically from the island of Palmarola in the latter case, are dated to levels equating to between 5800 and 5600 BC, pretty much on the Mesolithic/Neolithic divide for that region but nevertheless showing a definite communication by sea.

The presence of hunter gatherers along the northwestern Mediterranean coast during the Mesolithic period is often confined to caves or rock shelters displaying signs of repeated occupation. Mesolithic sites from which dates have been determined are Nerja cave and Bajondilla in Malaga province, Embarcadero del Rio Palmones and El Retamar in Cadiz province, Nacimiento and Valdecuevas in Jaen province and Ambrosio cave in Almeria. It is from some of these occupation sites that we find evidence of maritime activity although not necessarily maritime communication.

As far back as fifteen thousand years ago, the seasonal residents of Nerja cave in Malaga province in southern Spain, were fishing for deep water species, such as cod, presumably from dugout canoes. A shell midden in the cave was started about 10,980 BC and continued to grow until 9360 BC. Periwinkles and bivalves, including scallops, predominate together with the remains of fish including deepwater haddock and cod.

We have to wait until the 6th millennium BC before we see evidence of extensive coastal navigation along the northwestern seaboard of the Mediterranean.

Mesolithic contact with Africa

The Mesolithic period also saw evidence of potential contact between Andalucia and North Africa. A bone harpoon, of typical 'Mediterranean' barbed point design, turned up in a 12th millennium BC layer at Taforalt Cave in Morocco. It could have been picked up off the beach, flotsam taken home by a child, it could have been embedded in what must have been a rather large fish that escaped, or it could indicate physical communication across the Gibraltar Strait.

Ancient DNA Maghreb

On the 12th of March 2025, a report appeared in Nature Magazine that looked at a genomic study of ancient hunter gatherers from the Maghreb region in Tunisia. The study was co-led by David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

Ancient DNA analysis of individuals from Tunisia and northeastern Algeria showed they descended, in part, from European hunter-gatherers. This suggests sea voyages occurred across the Mediterranean around 8,500 years ago. A man from Djebba, Tunisia, had about 6% European hunter-gatherer DNA.

Possible origins of this European ancestry include Sicily and smaller islands between Sicily and Tunisia. The study shows the Mediterranean was not a barrier for stone age people.

Archaeological evidence such as obsidian found in Tunisia, originating from the island of Pantelleria, supports this theory.

References

Early Maritime Routes

Broodbank, C. (2013). 'The Making of the Middle Sea'. Thames & Hudson.

Cyprus

Simmons, A. H. (1999). Faunal extinctions in the early prehistory of Cyprus. Plenum Press. This book provides detailed analysis of the faunal remains at Aetokremnos, including the dwarf hippos and elephants, and discusses their extinction in the context of early human presence on the island.

Simmons, A. H., & Associates. (1999). Aetokremnos: A Late Pleistocene site in Cyprus. American Schools of Oriental Research. This is the primary excavation report for Aetokremnos, presenting comprehensive information about the site, its stratigraphy, artifacts, and dating.

Mandel, R. D., & Simmons, A. H. (1997). Geoarchaeology of Akrotiri Aetokremnos, Cyprus. Geoarchaeology: An International Journal, 12(2), 107-142. This paper focuses on the geoarchaeological context of Aetokremnos, examining the site formation processes and the relationship between the site and the surrounding environment.

Simmons, A. H. (2004). The Akrotiri Aetokremnos site and the colonization of Cyprus. In The Archaeology of Mediterranean Landscapes (pp. 163-178). Oxbow Books. This chapter discusses the significance of Aetokremnos in the context of the early colonization of Cyprus and the broader Mediterranean region.

Aegean

Betancourt, Philip P. "Prehistoric Aegean: From the Mesolithic to the end of the Bronze Age" provides information on the early use of Melos obsidian.

Strasser, Thomas & Panagopoulou, Eleni & Runnels, Curtis & Murray, Priscilla & Thompson, Nicholas & Karkanas, Panagiotis & Fw, Mccoy & Wegmann, Karl. (2010). Stone Age Seafaring in the Mediterranean: Evidence from the Plakias Region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Habitation of Crete. Hesperia. 79. 145-190. 10.2972/hesp.79.2.145.

Sampson, Adamantios. (2015) An Extended Mesolithic Settlement in Naxos: Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 16, No 1 (2016), pp. 269-271

Adamantios Sampson, J. K. Kozlowski, M. Kaczanowska, (2016) Lithic Industries of The Aegean Upper Mesolithic: Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 16 No 3, (2016), pp. 229-243

Crete

Strasser, Thomas & Panagopoulou, Eleni & Runnels, Curtis & Murray, Priscilla & Thompson, Nicholas & Karkanas, Panagiotis & Fw, Mccoy & Wegmann, Karl. (2010). Stone Age Seafaring in the Mediterranean: Evidence from the Plakias Region for Lower Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Habitation of Crete. Hesperia. 79. 145-190. 10.2972/hesp.79.2.145.

Tyrrhenian Sea

Chilardi, S., D.W. Frayer, P. Gioia, et al 1996. 'Fontana Nuova di Ragusa (Sicily, Italy) Southernmost Aurignacian Site in Europe.' Antiquity 70: 553-63.

"Characterization Of Obsidian Sources in Pantelleria, Italy" by Barbara A. Vargo: This study, available on Digital Commons @ USF, focuses on the procurement, processing, and distribution of obsidian from Pantelleria during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. It links the exploitation of Pantelleria obsidian to Neolithic communities in the region.

Klein Hofmeijer, G.K., 1997. 'Late Pleistocene Deer Fossils from Corbeddu Cave: Implications for the Human Colonisation of the Island of Sardinia.' Oxford Archaeopress.

Mussi, M., 2000. 'Heading South: The Gravettian Colonisation of Italy'.

Tykot, Robert H. "Obsidian Characterization and Provenance" (World Archaeology, 1995): This article discusses the methods used to identify the sources of obsidian and the distinctive characteristics of each source.

"Sardinian Obsidian: Production and Distribution in the Mediterranean Prehistory" Edited by R. D'Oriano, R. Maggi, and R. Tykot. This book provides a large amount of information concerning the distribution of Sardinian Obsidian.

The Lake Bracciano Canoes

Gibaja, J., Mazzucco, N., Mineo, M., & Canuti, A. M. (2024). The first Neolithic boats in the Mediterranean: The settlement of La Marmotta (Anguillara Sabazia, Lazio, Italy). PLOS ONE, 19(3), e0299765.

Central Mediterranean

Eleanor M. L. Scerri et al., Hunter-gatherer sea voyages extended to remotest Mediterranean islands, Nature (Published online: 09/04/2015), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08780-y

Balearic Islands

Onac, B.P., Polyak, V.J., Mitrovica, J.X. et al. (2024). Submerged bridge constructed at least 5600 years ago shows early human arrival in Mallorca, Spain. Commun Earth Environ 5, 457. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01584-4

Western Mediterranean

Cucart-Mora, Carolina & Gomez-Puche, Magdalena & Romano, Valeria & Fernandez-Lopez de Pablo, Javier & Lozano, Sergi. (2021). Reconstructing Mesolithic social networks in the Iberian Peninsula using ornaments. 10.31235/osf.io/yf6bj.

Fernandez-Lopez de Pablo, Javier & Puche, Magdalena. (2009). Climate change and population dynamics during the Late Mesolithic and the Neolithic transition in Iberia. Documenta Praehistorica. 36. 67-96. 10.4312/dp.36.4.

Guilaine, Jean & Manen, Claire. (2007). From the Mesolithic to Early Neolithic in the Western Mediterranean. Proceedings of the British Academy. 144. 21-51. 10.5871/bacad/9780197264140.003.0003.

First Crossings to Africa

Lipson, M., Ringbauer, H., Lucarini, G. et al. (2025). High continuity of forager ancestry in the Neolithic period of the eastern Maghreb. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08699-4

Fregel, R. (2018). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 115. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800851115

Simoes, L. G. (2023). Nature, 618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06166-6

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution