Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The Greek Emporium of Empuries 575 BC - 3rd c AD

Empuries is an ancient archaeological site on the Mediterranean coast of Catalonia, Spain. It is located within the Catalan comarca of Alt Emporda on the Costa Brava. The site is home to the remains of two ancient cities: the Greek city of Emporion, founded in 575 BC, and the Roman city of Emporiae, founded in 195 BC.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-29 | Last Updated 2025-05-17 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 6,179 times

The Serapieion - Empuries

When was Empuries founded?

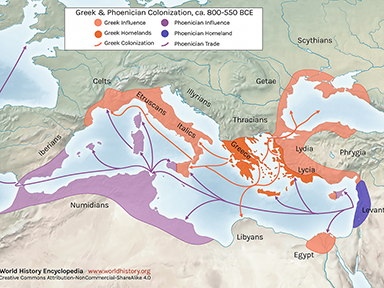

Empuries was founded in 575 BC by Greek colonists from Phocaea by way of Massalia, 300 kilometres northeast across the Gulf of Lion.

I suspect that the Greeks were invited to set up their trading post. Massalia is only a couple of hundred kilometres east of the northern extremities of the Iberian territory and the Indigetes were bound to have seen the benefits the Greeks brought to the Celts of Gaul. It was not long before the Indigetes also saw the benefits of 'Hellenization', a subject I will explore more fully when I look at the history of the Iberians.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Where was Empuries located?

Empuries was founded on a small island at the mouth of the river Fluvia (when the river was six kilometres south of its present estuary), in a region inhabited by the Iberian tribe, the Indigets. This city came to be known as the Palaiapolis, the "old city" when, towards 550 BC, the inhabitants moved to the mainland, creating the Neapolis, the "new city".

The island on which the Palaiopolis was situated is now part of the mainland and is the site of the mediaeval village of Sant Marti d'Empuries. The former harbour has silted up as well. Hardly any excavation has been done here.

Roses

Roses is 16 kilometres north of Empuries, across the Gulf of Roses. Its origins are unknown. Classical sources indicate it was founded in the 8th century BC by Geek colonists from Rhodes and that it was, at that time, called Rhode. However, archaeological evidence indicates a much later foundation, the 5th century BC. The town was probably first occupied by Massalian Greeks from the emporium across the bay. Perhaps a move by the more elite of the society from a crowded, thriving, port to a much more desirable area. It is a most scenic place and still very popular with tourists.

Discovering Empuries

Greek God of medicine, Ascleplus

The ruins of Empuries were discovered in the early 20th century. The first official excavations started in 1908 and were held by the Junta de Museus de Barcelona and directed by Emili Gandia i Ortega under the instructions of Josep Puig i Cadafalch and Pere Bosch-Gimpera. These excavations are still going on.

However, the precise location of the town was known since the 15th century, thanks to the work of the Catalan historian Pere Tomic. Tomic was the first to identify the ruins of Empuries with the ancient Greek city of Emporion.

Why was Empuries founded?

The Greeks founded Palaiapolis, later Empuries, in the first place for a number of reasons:

Abundant natural resources: The region around Palaiapolis was rich in natural resources, including wine, olive oil, grain, and metals. These resources could be traded with other parts of the Mediterranean world.

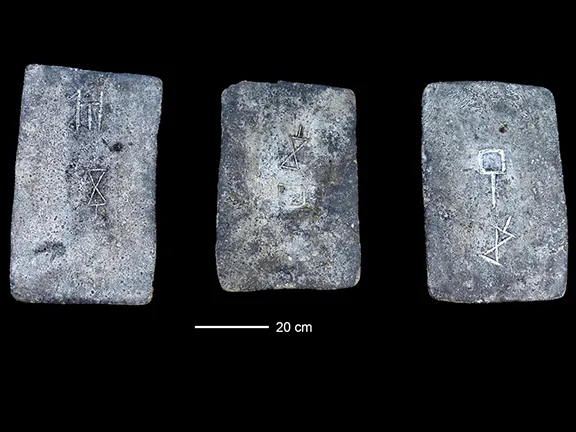

Some historians believe that the Greeks may have founded Palaiapolis as a way to secure access to tin, which was a valuable metal used in the production of bronze. Tin was mined in ancient Spain in the northwestern Iberian Peninsula, in the regions of Galicia and northern Portugal and in the Caceres region in central Spain. However, the route taken by the tin mined in Caceres and northern Portugal is most likely south via the Guadiana river valley where it emerges in the Atlantic Ocean west of Huelva, firmly in the Phoenician area of influence.

Access to trade routes: Palaiapolis was located on important trade routes that connected the Greek world with the Iberian Peninsula and beyond. This made it a major center of commerce and trade.

Spread of Greek culture: The Greeks founded Palaiapolis in part to spread their culture to the Iberian Peninsula. The city was a center of Greek learning and culture, and its citizens were fluent in the Greek language and literature.

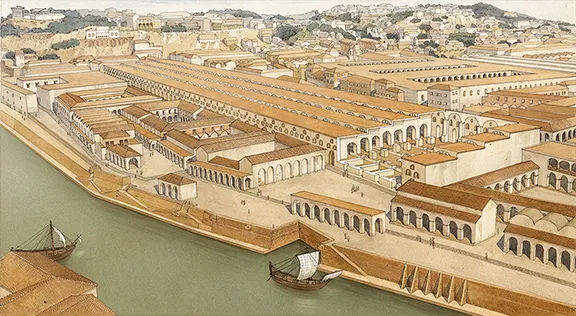

What did Empuries look like?

South Gate at Empuries

Founded during the 6th century and rebuilt and modified many times until the 2nd century BC, the ruins seen today bear little resemblance to the original town that lies beneath.

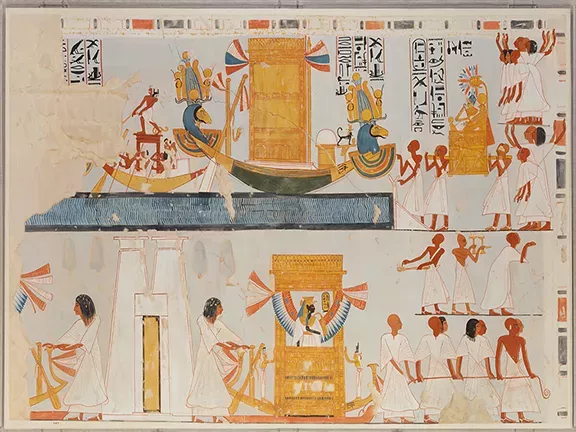

The whole town, about 200 metres x 130 metres, is enclosed by a wall that was extensively modified and strengthened between the 5th and 2nd centuries BC. The main gate was in the south wall and gave access to the temple area. The temples included one to the Greek God of medicine, Ascleplus (added 2nd century BC), and to the Hellenistic-Egyptian deities of Isis and Zeus-Serapis (added 1st century BC).

A main road led north through a fish salting area (of later, Roman vintage) and housing to the agora, the main public square. The impressive stoa or council house on the north side of the agora was rebuilt in the 2nd century BC. Beyond the agora was more housing and the old port, now agricultural land.

On a slight rise and to the west of the Greek city is the Roman city of Emporiae. To the south west of Emporiae is the Iberian-Greek necropolis that was in use from the 7th century BC until the Middle Ages. The early Greek and Iberian burials, from the 6th to the 3rd centuries BC, can be distinguished. The Greeks inhumed the deceased whilst the Iberians practised cremation.

It is difficult today to stand at Empuries and imagine the scene during the city's heyday. The port area is now beneath agricultural land and the foundations of the older buildings (before the 2nd century BC) in the city are still below the buildings now revealed by excavations.

The port must have been a hive of activity with dozens of cargo ships from other Greek city states and Phoenician ships from the Levant. They would be unloading their cargoes at the wharves. Smaller coastal boats would be loading, bound for smaller colonies and trading posts down the Mediterranean coast and returning with grain, olive oil, wine, lead, silver and copper.

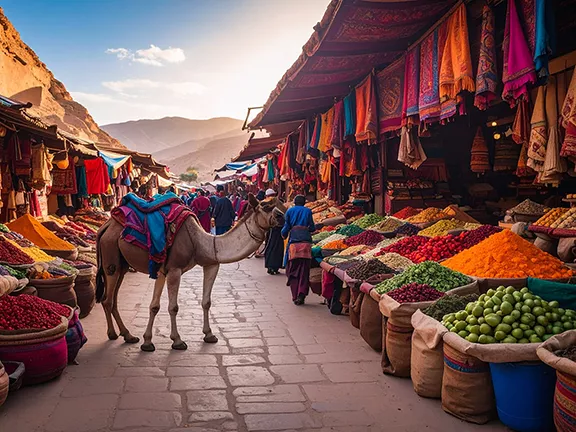

Temple officials would be busy, taxing imports and exports. The agora would have been a seething mass of traders, buying and selling the products imported into Empuries.

Local traders would be bringing their agricultural products into the city by road to exchange for exotic items from the east and a mixture of Phoenician gauloi (literally 'round ships') and smaller hippoi, would be bringing goods in from as far afield as Gades.

You could also expect to see the occasional Greek bireme or trireme, warships revictualing in the port.

What was traded in Empuries?

Left - Attic Crater Right - Bell Crater - Empuries

The Greeks are perhaps most famous for their imports of pottery. The earlier black figure pottery painting with its characteristic Greek figures, often warriors, on a reddish/brown background, was largely superseded by red figure pottery, red figures on a black background after the beginning of the 5th century BC. The latter was also produced in the Greek enclave of Magna Graecia (southern Italy) and much of the red figure pottery that ended up in the Iberian Peninsula was produced there.

Greek pottery, from huge kraters to delicate table wear was produced in vast quantities. Decoratively it was far in advance of anything that the Iberians or Tartessians could produce and was highly prized amongst the elite in northeastern and southern Spain. Huge amounts of it have been found and now repose in museums throughout Catalonia, Valencia, Murcia and Andalucia. The costumes worn by the figures depicted on the pots and vases were influential in the fashions of the Iberian and Tartessian elite.

The Greeks also imported statuettes and many of these display an Egyptian influence, an upright figure with straight arms to the side and left foot slightly extended.

Local tribes were also influenced by Greek sculptors, who in turn were influenced by Assyrian, Hittite and Egyptian artists, to the extent that locally taught sculptors started to produce Greek style work with their own, local, variations. The most famous are probably the damas, such as the Lady of Elche (and the hundreds similar), that all have evident Greek influence.

In return for imported exotic pottery in ceramics and bronze, glassware, figurines, scarabs, perfumes, fine linen and gold jewellery (often Phoenician), local grain, olive oil, wine, lead, silver and copper were exported to the eastern Mediterranean.

Who did the Empurians trade with?

It is becoming increasingly obvious that the Greek traders had a profitable relationship with the Phoenician colonies in the Iberian Peninsula with both Phoenician and Greek ships carrying each other's trade goods between colonies on the Iberian Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. Herodotus tells us that the Greeks traded with Tartessos, probably via the Phoenician colony at Huelva. Large amounts of Greek materials have been found alongside the Phoenician peninsular archaeological sites (for example in Villaricos, Almeria and at Toscanos, Malaga).

Another remarkable example of fruitful trade between the Greeks and Phoenicians are the numerous examples of Iberian grave goods that included valuable Greek ceramic materials, which have been found especially in the Iberian or Tartessian necropolis of the Peninsula at: Cabezo Lucero and Les Casetes (Alicante), La Hoya (Huelva), Castellones de Ceal and Toya (Jaen), Cerro del Santuario in Baza, Tutugi (Granada), at Pozo Moro, the Llano de la Consolacion and Los Villares de Hoya Gonzalo (Albacete) and at the Cigarralejo (Murcia).

Empuries effectively acted as a port of entry to the Iberian Peninsula.

To date, Empuries is the westernmost Greek emporium known. Strabo and Ptolemy tell us of other Greek colonies (as opposed to emporia) north of the Sucro (Segura) river:

Akra Leuka (that could correspond with the Ibero-Roman city of Lucentum in the Albufereta of Alicante).

Allon or Alonis (which would be located somewhere on the coastal strip from Villajoyosa to Calpe [Alicante], although there are authors who locate it in Santa Pola [La Picola], which Romans called Portus Ilicitanus.

Hemeroskopeion (which could be Denia).

To the south of the Segura the settlement of Mainake or Menace, another Greek colony according to Strabo, could have been located somewhere near Malaga, perhaps nearby the Cerro de los Villares, where a Phoenician settlement was previously established.

Archaeology has not been able to verify Greek settlements in these places, they are sometimes called ghost Greek towns, but the Greek influence was still present by way of the trade of Greek articles and the traces of the Greek alphabet in the Greek variant of the Iberian Script.

What happened to Empuries?

The relationship between Greeks and Phoenicians was generally one of cooperation until the late 7th century when Carthage started to emerge as a maritime power in its own right. The trading interests of Carthage came into direct conflict with those of the Greeks. In 537 BC, a newly emerging maritime power the Etruscans, allied themselves with the Carthaginians to prevent Greek expansionism in Corsica. Although the Greeks won the Battle of Alalia they suffered heavy losses. Carthage would fight two more major naval battles with Massalia, losing both, but still managed to close the Strait of Gibraltar to Greek shipping and thus contain the Greek expansion in Spain by 480 BC. It appears as though a probable border was established next to the mouth of the Segura River (where the town of Guardamar del Segura, Alicante, is currently located). To date, the northernmost Phoenician remains in the peninsular Mediterranean have been found in Guardamar del Segura.

Some historians consider that the lack of Greek traders in the Gibraltar Strait led to the collapse of the Tartessian civilization in Southern Spain, while the Carthaginian presence remained undisturbed. The uncontested, and more lucrative, river trade with the interior of Gaul became the focal point of the Greek cities of modern southern France, such as Massalia. Empuries declined in influence, trading mainly with the native Iberian tribe called the Indigets.

The Romans reached Empuries in 218 BC during the Second Punic War, which pitted them against the legendary Hannibal, the leader of the Carthaginian military troops. The Romans disembarked their legions, led by the Roman general Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus, in the port of the Greek city of Emporion to begin a journey around the Iberian Peninsula which allowed them to defeat the rear-guard of the Carthaginian army. Livy states that Gnaeus gained the support of the coastal peoples north of the Ebro by renewing old alliances and forming new ones. These would be the Iberian Indigets tribe and the Greeks in Emporion. This episode, which turned Empuries into the Roman port of entry to the Peninsula, was also the start of the conquest and Romanisation of the peninsula, which came to be known as Hispania.

In 195 BC, the Romans had to go back to Empuries and set up their military encampment there in order to put down the constant Indiget uprisings against the Roman occupation. Once peace was restored in the territory, the lands were given to Julius Caesar's veteran soldiers, who founded the Roman town of Emporiae. This town, which reached its peak during the imperial period and annexed the ancient Greek city of Empurion, was abandoned in the 3rd century AD.

Today the city has been partly excavated (almost 20% of its total area unearthed), and areas like the forum (institutional centre), the Roman baths, some domus (homes of the wealthy) and the amphitheatre can be visited.

References

Empuries: City of Two Cultures by Margaret E. Miles

Empuries: A Greek and Roman Town in Spain by John Rich

The Archaeology of Empuries by Andrew J. Brown

Empuries: An Archaeological Guide by Josep Maria Nolla-Brufau

Empuries Archaeological Site (official website)

Archaeology Museum of Catalonia - Empuries branch - personal visit

Empuries en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emp%C3%BAries

Empuries: An Ancient Greek and Roman City in Catalonia, Spain (Smithsonian Magazine article)

Empuries: A Greek Emporium in Catalonia, Spain (Ancient Origins article)

Empuries: City on the Edge of the World by John Haywood (2003)

Empuries: A Greek City on the Iberian Coast by Josep Guitart i Duran (2007)

Empuries: Guia arqueologica by Josep Guitart i Duran (2010)

https://guia-arqueologica.com/phoenicians-and-greeks-spain/

Geography of Strabo: Book III, 4, 6,

Geography of Ptolemy: II, 6, 4

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution