Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The World’s First Postal and Courier Services

The origins of postal and courier services, from Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi's Egyptian runners and Mesopotamian cuneiform carriers to Darius the Great's efficient Persian Royal Road and Chapar Khaneh system. How ancient communication networks shaped empires.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-23 | Last Updated 2025-07-23 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 2,617 times

Sargon the Great and Cuneiform Tablet

Bronze Age Communication Networks in the Middle East

The administrative prowess of ancient civilizations often depended on the efficiency of their communication systems. While monumental architecture frequently captures our imagination, the sophisticated networks that transmitted knowledge and authority across vast territories are often unconsidered. Yet, these communications systems were the ‘glue’ that held these mighty civilisations together. Let us look at two of those civilisations, Egypt and Mesopotamia, and the structures they put together to transmit information from one end of their empires to the other.

The Visionary Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi

Our narrative begins not with grand structures, but with the visionary leadership of Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi.

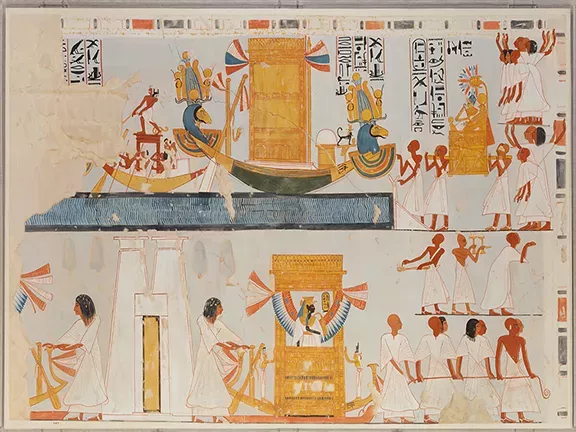

Around 2400 BC, this often-overlooked ruler of the Fifth Dynasty reshaped the landscape of Egyptian governance by establishing the world's earliest known courier service. Resolute runners traversed the full 2,500-kilometre expanse of the Egyptian kingdom, carrying papyrus scrolls inscribed with royal decrees and vital intelligence in hieroglyphic script. This early system cemented the Pharaoh's authority, ensuring timely dissemination of information across a sprawling realm.

The Bureaucracy of Ancient Mesopotamia

Egypt did not stand alone in its pursuit of rapid communication. In southern Mesopotamia, a parallel revolution in governance unfolded under King Sargon of Akkad, known to history as Sargon the Great, and his successors from approximately 2334 BC.

Here, a burgeoning hierarchical bureaucracy and centralized government necessitated a robust communication infrastructure. Archaeologists have unearthed over 150 cuneiform letters from this period, predominantly written in Akkadian. These missives, typically 10 to 25 lines in length, offer intimate glimpses into daily life, detailing personal matters, legal disputes, real estate transactions, and economic concerns.

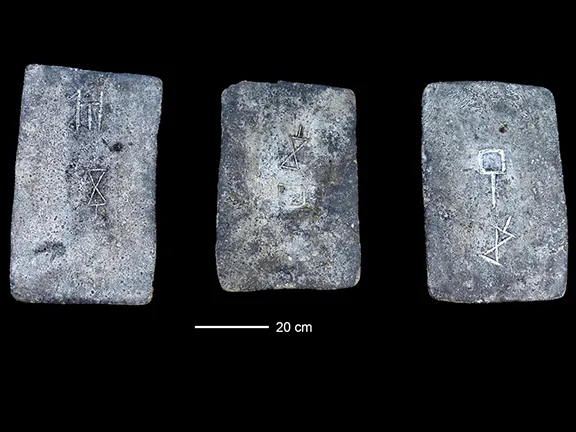

Clay Tablets and Cuneiform: Unlike the Egyptians, who leveraged readily available papyrus, Mesopotamian scribes relied on a different medium. Lacking access to papyrus, they adopted cuneiform script, a system of wedge-shaped characters ideally suited for impression upon soft clay tablets. It is crucial to understand that cuneiform itself is not a language, but rather a sophisticated writing system distinct from an alphabet. Comprising between 600 and 1,000 characters, cuneiform rendered words phonetically by dividing them into syllables – akin to 'ca-at' for 'cat' or 'mu-zi-um' for 'museum.' This versatile script accommodated a multitude of languages, including Akkadian, Sumerian, Eblaite, Hurrian, Elamite, and Hittite, underscoring its widespread utility across diverse cultures.

The Invention of the Envelope: The ingenuity of these ancient communicators even extended to the "envelope." Scribes encased clay tablets in additional layers of clay, which bore the identities of the correspondents and the sender's seal impression. Couriers then wrapped these encased tablets in protective textiles and leather, transporting them via donkey caravans or specialized messengers. This early form of secure packaging ensured the integrity and privacy of the transmitted information.

Enter the Merchant Trader Oligarchs

The benefits of swift communication extended beyond the exclusive domain of kings and pharaohs. By 2000 BCE, the growing class of merchant traders recognized its commercial imperative. During the early centuries of the 2nd millennium BC, Assur, an Assyrian city-state perched above the Tigris River, flourished under an oligarchy of merchants. These enterprising individuals developed extensive long-range trade networks into central Anatolia, establishing and organizing trading outposts, with Kanesh (modern-day Kultepe, Turkey) emerging as the most prominent. A remarkable 22,500 Assyrian cuneiform tablets, predominantly from the private archives of merchants, have been recovered from houses in Kanesh's lower town. These invaluable records comprise letters, legal documents, and personal notices, providing a unique insight into the commercial life of the era.

Communications Between Empires during the Bronze Age

The Mari Letters: Further south in Mesopotamia, the Mari tablets, penned around 1800 BCE, offer another glimpse into the royal correspondence of the period. These substantial clay tablets, some measuring 25 x 20 centimetres and several centimetres thick, detail intricate political and diplomatic exchanges. Among the prominent figures mentioned is the celebrated lawgiver Hammurabi of Babylon, alongside the king of Aleppo, whose dominion included the city of Alalakh.

Unlike their Egyptian counterparts, couriers transporting these weighty Mari tablets likely utilized chariots, providing a practical solution for the bulk of these significant messages. The Mari letters represent a fraction of the more than five thousand Old Babylonian letters recovered, exchanged between rulers, officials, and private citizens, collectively illuminating the intricate social fabric of the age. It was Hammurabi, incidentally, who famously codified the principle of "An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth," a legal tenet that would resonate over a millennium later in the biblical book of Leviticus. He also prescribed the rather specific penalty, "If anyone bites off the nose of a free person, he shall pay 40 shekels of silver." One can only ponder the frequency with which such a fine was levied.

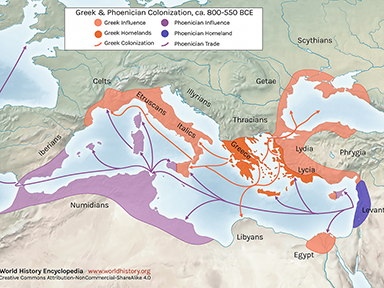

The Amarna Letters Period: By the time of the Amarna letters, written between 1360 and 1332 BC, the "civilized world" had expanded considerably. It now encompassed Mycenaean Greece, Hatti, the Kassite kingdom of Babylon, Assyria, and Mitanni – a vast geographical expanse that includes modern-day Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, parts of Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Gaza, Sinai, and Egypt. All these entities possessed their own sophisticated courier systems, which had become increasingly interconnected. Imagine the seamless flow of information across continents and seas, facilitated by dedicated individuals who braved tempestuous waters, scorching deserts, and treacherous terrain. These networks were much more than message delivery systems; they functioned as vital arteries, circulating not only official correspondence but also cultural ideas and commercial goods. The Amarna archive, a veritable treasure trove of letters exchanged between rulers, offers an unparalleled window into this vibrant, interconnected Bronze Age world. Over 380 letters have been recovered from this archive, exchanged between the rulers of various city-states and the two Egyptian pharaohs of the period: Amenhotep III (1388-1351 BC) and Amenhotep IV (1351-1334 BC).

Horses or Chariots: The debate persists among historians regarding the role of horses in early Bronze Age courier services. While direct riding may not have been common at this nascent stage, chariots undeniably played a crucial role, particularly in mitigating the burden of transporting heavy clay tablets. As technological advancements progressed, horses gradually assumed their place as dependable mounts, undoubtedly providing couriers with much-needed assistance.

One can imagine the magnificent spectacle: a light chariot, emblazoned with the king's insignia, drawn by four horses, hurtling along a dusty road at speeds approaching 60 kilometres per hour, flanked by sword-and-shield-wielding cavalry. Such a cavalcade would have raised a visible cloud of dust for miles, each "unsung hero" striving to complete their route in record time. These feats of speed and endurance likely fuelled grand tales in the post houses, inspiring the Greeks over a thousand years later to incorporate chariot racing into the inaugural Olympics and the Romans to construct grand hippodromes for similar spectacles.

Diplomatic Immunity for Couriers: Despite the apparent sophistication of these networks, the concept of diplomatic immunity, as we understand it today, was largely absent. Rulers harboured understandable paranoia about allowing potential spies into their inner circles. Consequently, couriers and their armed escorts faced the precarious reality of being detained by the recipients of their messages at the whim of a king or pharaoh. Indeed, historical accounts suggest that some couriers endured years of imprisonment before being permitted to return to their homelands; tragically, some even perished in captivity. Therefore, in addition to the omnipresent threats of bandits and robbers enroute, couriers confronted the severe risk of arbitrary detention upon reaching their destination. Being a courier was undeniably a perilous profession.

Sadly, between 1300 and 1100 BC, the flourishing Bronze Age civilizations experienced a catastrophic collapse, dragging this intricate communication network down with them. Centuries would pass before a comparable system re-emerged under the ambitious Persian Empire in the 5th century BC.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Iron Age Royal Road and Chapar Khaneh of Darius the Great

The Achaemenid Persian Empire and Royal Road

The clatter of hooves, the shouts of riders, the swift exchange of messages – this was the rhythm of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, an empire stitched together not just by conquest, but by an astonishing feat of ancient engineering: the Chapar Khaneh, or Royal Road system, established by Cyrus the Great (559 to 530 BC), and perfected by Darius the Great (522 to 486 BC). More than mere pathways, these paved roads were arteries of power, and at their heart lay the chapar khaneh – the post houses that facilitated the fastest communication network the ancient world had ever seen.

Darius the Great’s Vision

In the first millennium BC, news again travelled at the pace of a camel or a marching army. Yet, Darius understood that to govern a vast empire stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River, he needed to know what was happening, and he needed his commands to reach their destinations swiftly. His solution, inspired by an even older courier service developed by the Egyptians during the Bronze Age, was nevertheless ingenious.

The Royal Road: The most famous section of this network was the Royal Road itself, a monumental achievement often described as running approximately 2,699 kilometres from Susa, one of the Persian capitals, to Sardis in Lydia. Along this incredible span, Darius established a system of chapar khaneh at regular intervals, typically a day's ride apart.

The Chapar Khaneh: These post houses were not simply stables. They were vital logistical hubs, staffed with fresh horses and expert riders known as chapar established, on average, 32 to 40 kilometres apart, or one day’s ride. A messenger, bearing dispatches, would arrive at a chapar khaneh, where he would pass his dispatches to a fresh rider with a rested horse. Herodotus, the Greek historian, marvelled at the efficiency of this system, famously writing, "There is nothing in the world that travels faster than these Persian couriers." He adds, "Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds." This phrase, often associated with modern postal services, originated in his description of Darius's couriers, underscoring their unwavering dedication.

The Angoras :The couriers, known as angaros by the Greeks, could deliver a message from one end of the Royal Road to the other in a matter of nine days. The same journey on foot took ninety days.

The angaros were highly efficient mounted couriers of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. They were the key personnel who operated the Chapar Khaneh system, ensuring the swift transmission of messages across the vast empire.

Essentially, the angaros were the mail carriers, but far more than just delivering letters. They were specially selected and highly trained riders who had to be incredibly swift and dedicated.

Controlling an Empire: The chapar khaneh and angoras allowed Darius to maintain tight control over his satrapies (provinces), receive intelligence rapidly, and dispatch orders to his regional governors and military commanders with unprecedented speed. Rebellions could be quelled more effectively, and trade could flourish with greater security. This rapid communication was a key factor in the stability and longevity of the Achaemenid Empire.

Beyond their practical function, the chapar khaneh were symbols of imperial power and organization. They represented Darius's ambition to unify his diverse empire not just through military might, but through efficient administration.

Unearthing the Chapar Khaneh: While no physical chapar khaneh from this period survive intact today in their original form, archaeological excavations along the likely routes of the Royal Road have uncovered remains of settlements and structures that align with the descriptions of these post houses. These scattered remnants offer tantalizing glimpses into the infrastructure that supported one of history's most impressive communication networks.

Herodotus Waxes Lyrical

Herodotus was a Greek historian living in Persian controlled Halicarnassus. In about 440 BC, he wrote ‘The Histories’, in which he describes the Royal Road and the chapar khanehs:

‘Now the true account of the road in question is the following: Royal stations exist along its whole length, and excellent caravanserais; and throughout, it traverses an inhabited tract and is free from danger. In Lydia and Phrygia there are twenty stations within a distance of 94½ parasangs. On leaving Phrygia the Halys has to be crossed; and here are gates through which you must needs pass ere you can traverse the stream. A strong force guards this post. When you have made the passage, and are come into Cappadocia, 28 stations and 104 parasangs (an ancient Persian unit of length that varied but is generally estimated to be about 4.8-5.6 km) bring you to the borders of Cilicia, where the road passes through two sets of gates, at each of which there is a guard posted. Leaving these behind, you go on through Cilicia, where you find three stations in a distance of 15½ parasangs. The boundary between Cilicia and Armenia is the river Euphrates, which it is necessary to cross in boats. In Armenia, the resting-places are 15 in number, and the distance is 56½ parasangs. There is one place where a guard is posted. Four large streams intersect this district, all of which have to be crossed by means of boats. The first of these is the Tigris; the second and the third have both of them the same name, though they are not only different rivers, but do not even run from the same place. For the one which I have called the first of the two has its source in Armenia, while the other flows afterwards out of the country of the Matienians. The fourth of the streams is called the Gyndes, and this is the river which Cyrus dispersed by digging for it three hundred and sixty channels. Leaving Armenia and entering the Matienian country, you have four stations; these passed you find yourself in Cissia, where eleven stations and 42½ parasangs bring you to another navigable stream, the Choaspes, on the banks of which the city of Susa is built. Thus, the entire number of the stations is raised to one hundred and eleven; and so many are in fact the resting-places that one finds between Sardis and Susa.’

He goes on to describe the angaros:

‘Now there is nothing mortal which accomplishes a journey with more speed than these messengers, so skilfully has this been invented by the Persians: for they say that according to the number of days of which the entire journey consists, so many horses and men are set at intervals, each man and horse appointed for a day's journey. These neither snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness of night prevents from accomplishing each one the task proposed to him, with the very utmost speed. The first then rides and delivers the message with which he is charged to the second, and the second to the third; and after that it goes through them handed from one to the other, as in the torch-race among the Hellenes, which they perform for Hephaestus. This kind of running of their horses the Persians call Angarium.

Darius's Chapar Khaneh system was, in essence, the internet of the ancient world. It shrank the vast distances of his empire, bringing distant corners closer to the imperial centre and enabling a level of centralized control previously unimaginable.

Leave it to the Romans

The Romans were not slow to appreciate and adopt foreign innovations. One such innovation was the road and track networks established by Darius the Great. It laid the foundations for the superb road network the Romans built throughout their Empire.

Meybod: A Chapar Khaneh from Modern Times

One well preserved example of a chapar khaneh still exists at Meybod in Iran. It dates from the Qajar Era (1789 to 1925 AD) and now houses a museum of postal communications history. The chapar khaneh system still worked some two thousand years after its inauguration.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution