Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

Bronze Age Economies in the Mediterranean: Trade Without Coins

How did the Bronze Age economy in the Mediterranean work without coins? Merchants developed sophisticated economic systems during the Bronze Age, from Egypt's deben to Mesopotamian silver. How East met West through silent trade and standardized ingots—long before the first coin.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-17 | Last Updated 2025-07-19 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 3,645 times

Ancient Middle East Market Scene - AI generated

Bronze Age Economic Revolutions in the Mediterranean Basin

How did Bronze Age merchants conduct business before the invention of coins? The Bronze Age, stretching from roughly 3300 to 1200 BC, was an age when sophisticated, adaptable, and often strikingly complex ways of doing business developed, long before the introduction of coins. Forget the clinking of coins and familiar currencies; these ancient economies functioned with an ingenious blend of standardized weights, abstract value systems, and meticulous accounting.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Economy of Ancient Egypt

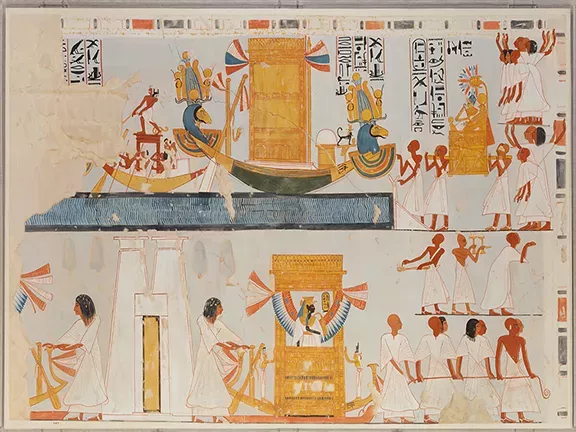

We start on the fertile banks of the Nile, in ancient Egypt. Envisage a crowded Egyptian market; stalls heaped with colourful spices from distant lands, local vegetables, rugs and gowns, men and women haggling at the tops of their voices, laden donkeys and camels threading their way through the teeming throng. In the midst of this apparent chaos, how did transactions take place? For much of its illustrious history, from the dawn of the Old Kingdom right through the New Kingdom, ancient Egypt operated without coinage as we know it today. Their system revolved around a fascinating unit of value: the deben.

The deben wasn't a coin you held in your palm. Instead, it was primarily a unit of weight, most commonly of copper, but also of silver and gold. Look at it as a mental ledger: a certain amount of grain, an exquisitely crafted vase, or even a day's labour was assigned a value in debens. A papyrus from Deir el-Medina, the village of the tomb builders, for instance, records a fish valued at a quarter of a deben of copper. This wasn't a physical exchange of copper; it was a recognized equivalence, a shared understanding of worth.

This notional currency evolved over time. Early evidence for the deben surfaces in the Early Dynastic Period (about 3150-2686 BC), specifically from the Second Dynasty. Copper and gold debens were probably circulated from these very early times. By the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2181 BC), the deben was firmly entrenched as a unit of value. Tomb paintings vividly show balance scales and weights, undoubtedly debens, facilitating transactions. The Middle Kingdom (c. 2055-1650 BC) saw increased sophistication; distinct "gold deben" of around 13.6 grams, and "copper deben" around 27 grams, emerged. The New Kingdom (c. 1550-1069 BC) brought further refinements, with the deben becoming heavier (around 90-95 grams) and subdivided into ten kidet (or kite). It remained the primary benchmark for valuing goods, especially copper and silver.

While a mental concept, the deben sometimes took on a physical form. Archaeologists have unearthed numerous ring-shaped copper ingots, often weighing one deben or fractions thereof. These weren't coins, but rather convenient, pre-weighed units of copper, easily stored, transported, and cut for smaller transactions.

Dr. Wolfram Grajetzki, a renowned Egyptologist, reminds us, "These rings were not money in the modern sense, but they were certainly a practical way to deal with the value of copper."

This adaptable, multi-tiered system, with copper for everyday goods and silver or gold for higher value items, allowed for everything from a pair of sandals to an entire estate to be valued and exchanged. This system, relying on trust and agreed-upon weights, speaks volumes about the communal and relational nature of Egyptian economic life.

The Mesopotamian Marketplace: Barley, Silver, and Tablets of Trust

Travel east to Mesopotamia and the Levant, and you discover an equally sophisticated, yet distinct, economic landscape during the same Bronze Age period (roughly 3150-525 BC). Here, the absence of minted coins was also the norm, but the "currencies" of choice differed.

While direct barter – the simple exchange of goods for goods – certainly occurred, it was rarely the sole mechanism for an entire society. True, a farmer might swap surplus grain for a potter's wares, but large-scale or complex transactions demanded more. Historians now understand that pure barter was generally limited to specific, infrequent exchanges where a "double coincidence of wants" aligned.

Instead, Mesopotamia embraced commodity money, with barley and silver serving as widespread standards. Barley, the fundamental staple, often functioned as a medium for local transactions, wages, and loans. Its value was stable and universally understood, with contracts frequently specifying payments in it. For larger dealings, long-distance trade, and as a durable store of value, silver reigned supreme. It wasn't minted into coins, but rather exchanged in recognisable forms – rings, coils, or cut pieces – meticulously weighed on scales. Clay tablets, the ubiquitous records of Mesopotamian life, are filled with transactions priced in silver, even when the actual payment involved textiles, oil, or other commodities. Silver functioned as a "money of account," a universal measuring stick for value.

Mesopotamia developed its own system of standardized weights that paralleled Egypt's deben. The shekel, a unit of weight that varied slightly by region and time, often 8-11 grams of silver, and the mina, typically 60 shekels, provided a consistent basis for valuation across the region. The earliest evidence for the shekel as a weight unit dates back to around 3000 BC in Mesopotamia, with specific mentions in records from Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2150 BC) and the famous Code of Hammurabi (c. 1700 BC). This widespread adoption made it the common standard for weighing silver and gold in trade.

Beyond physical commodities, Bronze Age Middle Eastern societies excelled in credit and debt systems. Clay tablets carefully recorded loans, advances, and future payments. Temples and palaces, as powerful economic institutions, actively extended credit, managed payments, and oversaw vast inventories. This allowed for complex economic activities and long-term projects without requiring immediate physical exchange. The Kanesh Archives, discussed in other articles, reveal astonishing details of these complex credit transactions that occurred between 1920 and 1850 BC.

Furthermore, gift exchange and reciprocity played a significant role, particularly in diplomacy and social hierarchies. Kings exchanged lavish presents to solidify alliances and demonstrate wealth, creating intricate webs of obligation. Within communities, favours and goods were exchanged without an immediate, equivalent return, fostering strong social bonds. The Amarna letters, discussed in other articles, provide intriguing details of the lavish gift exchanges that underpinned diplomatic relations between elite rulers during the 14th century BC.

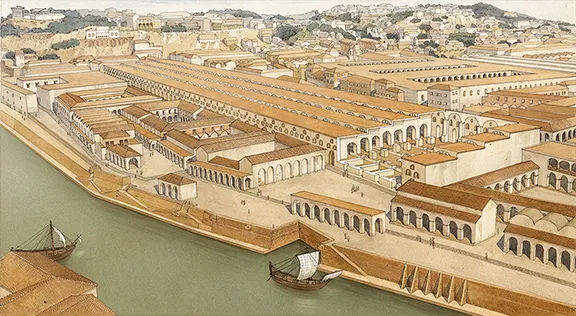

Large-scale, institutional trade also flourished. Temples and palaces dispatched specialized merchants, known as tamkarum in Sumer and Akkad, to acquire scarce resources like copper, tin, precious stones, and timber from distant lands. These institutions produced goods, often textiles from their own workshops, to exchange for these vital raw materials. Major cities like Ur, Mari, Ebla, and Ugarit emerged as vital trade hubs, connecting vast networks that stretched to the Indus Valley and Afghanistan.

Canny merchants quickly learned to exploit value differences between regions. For instance, a merchant may swap a shekel’s worth of silver in Kanesh for amber, much prized in Egypt. In Egypt he would swap the amber for two debens worth of gold, which would be worth 2 shekels worth of silver back in Kanesh.

The First Coins: A Late Bronze Age Revolution

Lydian Stater 561 - 546 BC

While the deben and shekel systems served for millennia, the real revolution in exchange arrived much later, in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. The concept of minted coinage, that familiar piece of metal bearing an official stamp, did not originate in Egypt or Mesopotamia.

The credit for the first minted coin typically goes to the Lydian Stater, produced in the Kingdom of Lydia (modern-day western Turkey). These early electrum (a natural gold-silver alloy) coins emerged in the second half of the 7th century BC, probably during the reign of King Alyattes (c. 610-560 BC). What made them groundbreaking? They boasted a standardized weight and purity, eliminating the need for constant re-weighing, and carried an official authority stamp – often a lion's head – guaranteeing their value.

This state-backed guarantee proved an ingenious innovation, transforming a lump of metal into a universal, trusted medium of exchange. Later, King Croesus (c. 560-546 BC) further refined this by introducing coins of pure gold and pure silver, establishing the world's first bimetallic monetary system.

The shift to a cash economy in the Middle East was gradual. In Egypt, the deben system persisted into the Late Period (c. 664-332 BC), but the influence of Greek practices increasingly introduced coinage. The full transition didn't fully solidify until the Persian invasion in 525 BC. Similarly, while the shekel had been a unit of weight since 3000 BC, actual minted "shekel" coins only began appearing in regions like Phoenicia and later Judaea from the 4th century BC onwards.

So, the popular image of ancient Middle Eastern markets clinking with coins is largely a historical anachronism. For thousands of years, these dynamic societies developed practical economic systems based on abstract units of value, standardized weights, meticulous record-keeping, and widespread trust. They built empires, conducted international trade over vast distances, and managed complex economies, all without a single coin in sight. It demonstrates that "doing business" in the Bronze Age Middle East was far more advanced and fascinating than commonly perceived.

How the Economies of the West Worked during the Bronze Age

While the grand narratives of Egyptian pharaohs and Mesopotamian city-states often dominate our view of the Bronze Age, Western Europe was far from an economic backwater. Here, Indigenous societies developed their own systems of exchange, independent of Eastern influences, rooted in their unique resources and social structures. The "currencies" of the Bronze Age West were often everyday necessities or tools crafted with remarkable precision.

Take a village community in what is now modern-day Spain or Italy around 2000 BC. They certainly practiced direct barter, swapping surplus grain for a neighbour’s pottery. But for more significant transactions, or for accumulating wealth, they developed their own forms of commodity money.

One prime example comes in the form of bronze objects themselves. Not every bronze item, but specific types, often found in hoards, show a surprising standardization. Certain axe heads, for instance, or simple bronze rings and rib-shaped ingots, display remarkably consistent weights across far-flung regions. This wasn't accidental; artisans manufactured them to be easily interchangeable, acting as units of value. They might have been too small for heavy work or even deliberately non-functional, signalling their primary role as a measure of worth rather than a tool. This deliberate uniformity allowed communities to accumulate wealth, pay for services, or exchange for distant goods without constantly re-weighing every transaction.

Beyond metal, other vital commodities also served as highly valued items in regional exchange.

Long before the Romans paid their legionnaires with salt, "white gold" as it was known to ancient peoples, was indispensable for preserving food and sustaining life. Its limited natural sources meant communities without access to salt springs or coastal evaporation pans relied heavily on trade to acquire it, potentially using it as a high-value medium for exchange, particularly in inland regions.

Though perishable, textiles and wool also played a significant economic role. The Bronze Age saw a "wool revolution" across Europe, making finely woven cloth a valuable, labour-intensive product. While direct evidence is scarce, it's plausible that standardized textiles served as a form of payment or exchange for other goods and services within local and regional networks.

The discovery of amber, especially from the Baltic, further highlights specialized trade within the West. Its exotic beauty and perceived mystical properties made it a highly prized prestige item, circulating among elites and forming part of gift exchanges that solidified social bonds and alliances.

Built on shared understanding and local resources, these systems show that Western Bronze Age societies were not isolated. They possessed vigorous and robust internal economies, driven by necessities, craftsmanship, and a clear understanding of value, long before distant traders ever appeared on their horizon.

When East Met West: Dumb Barter

Myceanean cargo ship on beach - AI generated

How did the experienced international traders from the established powers of the Eastern Mediterranean, with their advanced ships and structured economies, first forge bonds and conduct business with the often-uncontacted Indigenous inhabitants of the Western Mediterranean? The answer, particularly in the earliest encounters, plausibly lies in a remarkably ingenious and ancient method: silent trade, sometimes called "dumb barter." This system, where "dumb" refers to the absence of spoken words, allowed commerce to thrive even without a shared language or established trust.

Imagine the scene: a foreign ship, perhaps a sleek Mycenaean vessel, cautiously approaches an unfamiliar Western coastline. Laden with their distinctive pottery, bronze tools, and glass beads, Eastern sailors would land on a neutral beach or a designated, open space. They would carefully lay out a selection of their goods, announce their arrival by lighting a fire, then conspicuously withdraw, perhaps retreating to their boats or a safe distance from shore. The later Phoenician preference for inshore islands and conspicuous promontories for their trading post is well known and probably reflects the location of these first trading sites.

Observing from a hidden vantage point, the Indigenous inhabitants, , would then approach the deserted spot. They would inspect the foreign wares, and if interested, place alongside them what they deemed an equivalent value in their own commodities – perhaps raw copper, tin, amber, or local hides. Then, they too would withdraw.

The original traders would return, examine the offer, and if satisfied, take the Indigenous goods, leaving their own. If not, they would leave the offer untouched, signalling their rejection, and retreat again, prompting the locals to adjust their proposal.

This fandango of deposit, withdrawal, and assessment, was repeated until both parties were content, allowed trade to occur with minimal risk of misunderstanding, hostility, or the immediate need for complex social overtures. ‘Dumb Barter’ bridged enormous cultural divides with a shared language of value and a cautious, yet ultimately successful, pursuit of mutual gain. Ultimately, this foundational system paved the way for more direct, formalized trade relations, as trust gradually began to replace apprehension.

When East Met West: A Mediterranean Economic Symphony

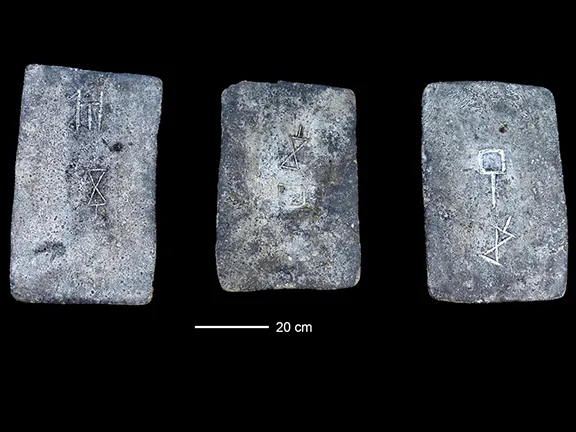

Oxhide ingot from Mycenaen port of Kymi, Euboea

When we contemplate the growing interaction between the established economic giants of the Eastern Mediterranean and the increasingly mature communities of the West, we see that ‘dumb barter’ was gradually replaced with more practical methods of exchange.

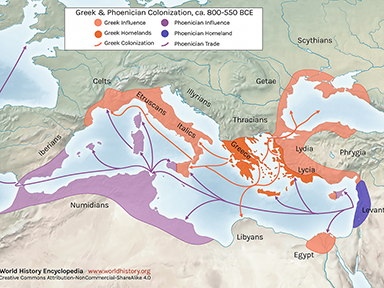

From roughly the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, adventurous sailors from the Aegean (Mycenaeans), Cyprus, and the Levant increasingly ventured beyond the familiar eastern shores, pushing towards Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Iberian Peninsula. This wasn't merely a transfer of goods; it was a complex economic dialogue, integrating Eastern practices with Indigenous Western traditions and spawning new forms of "currency."

The primary driver for these daring voyages was metal. The Eastern Mediterranean, though technologically advanced, lacked sufficient local copper and tin. The West, by contrast, possessed huge deposits, particularly in Sardinia (copper, lead) and the Iberian Peninsula (copper, tin, silver). This resource imbalance created a powerful incentive for long-distance trade.

It was in this context that the iconic "ox-hide" ingots came into their own. While originating in the East (Anatolia, Cyprus), these large, four-handled copper ingots, weighing around 29 kilogrammes became a universal medium of exchange across the entire Mediterranean. They were a standardized, portable, and easily recognizable form of concentrated wealth. Picture a Mycenaean ship laden with pottery and textiles arriving in a Sardinian harbour; the exchange wouldn't be for loose chunks of copper, but for these pre-weighed, trust-worthy ingots.

Other forms of standardized metal ingots also facilitated this East-West exchange. "Bun ingots" – plano-convex copper ingots, shaped like small loaves of bread – are found across the Mediterranean, indicating another standardized unit for smaller metal transactions. These items weren't just goods; they were a common language of value, allowing diverse cultures to "speak" the same economic terms.

The exchange went far beyond raw materials. Eastern traders brought highly sought-after prestige items: Mycenaean pottery, intricate Cypriot bronzes, glass beads from Egypt and the Levant, and carved ivory. These objects weren't "currency" for everyday purchases, but they were vital in reinforcing social hierarchies in the West. Local chieftains and elites coveted these exotic imports, using them to display wealth and cement alliances. In return, the West offered not only its invaluable metals but also its unique resources like amber from the Baltic (which reached Mycenaean Greece and even Egypt, via intricate overland and maritime routes) and perhaps even specialized tools or materials that appealed to Eastern tastes.

This interaction wasn't simply one-sided absorption. Western communities, like the Nuragic people of Sardinia, actively engaged in this trade. They weren't just passive recipients but skilled producers of copper and bronze objects, often adapting Eastern techniques and even influencing aspects of Eastern metalwork. The exchange fostered shared technologies, artistic motifs, and even weight standards, creating a truly interconnected Bronze Age Mediterranean. The lack of coins forced traders to be ingenious, fostering a remarkable sophistication in recognizing and exchanging value across vast cultural and geographical divides. It was a genuine economic symphony, played out on the ancient seas, long before the first coin ever left its stamp.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution