Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The Development of the Ancient Sea Trade Routes in the Mediterranean Sea

This is the story of the development of the ancient sea routes through the Mediterranean starting with purely local coastal networks and working up through the routes established by the Minoans, Phoenicians, Greeks, Etruscans, Carthaginians and Romans.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-09-20 | Last Updated 2025-05-17 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 63,528 times

Greek and Phoenician Dominance of the Mediterranean by 550 BC

The Mediterranean Sea as the Centre of the Ancient World: Exploring Mare Nostrum's Significance

Until the arrival of Europeans in the Americas in the 15th century, the Mare Nostrum, otherwise known as the Mediterranean Sea, was the centre of the world.

What role did early Middle Eastern civilizations like Egypt, Babylonia, and Assyria play in driving Mediterranean trade?

The civilisations that developed first in the Middle East, such as Egypt, from 3500 BC, the Babylonian from 1884 BC, and the Assyrian Empire after 1365 BC were a magnet for luxury goods from far afield.

Investigating the trade networks established by the Minoans, Phoenicians, Greeks, Etruscans, Carthaginians, and Romans in the Mediterranean.

Later societies such as the Minoans, Phoenicians, and Greeks, established maritime trading networks throughout the Mediterranean to satisfy the demands of the emerging empires. The Greeks became an Empire in their own right, whilst the Minoans, Phoenicians and Carthaginians created trading empires.

Understanding the vast maritime trading network created by the Roman Empire: Mare Nostrum's peak.

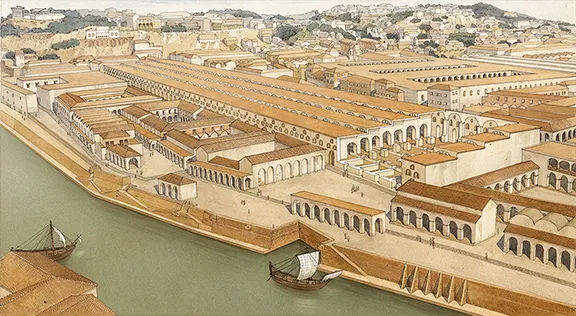

The Romans arrived and created the largest Empire the world had known until then, together with the most expansive maritime trading network.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Tracing the Origins of Mediterranean Trade: From Mesolithic Overland Routes to Early Sea Voyages

Mesolithic Seafaring

Trade started in the Mediterranean Basin much earlier with overland routes to places as far afield as the Balkans. Those routes developed over a huge length of time from the Mesolithic period about 25,000 years ago.

What were the earliest long-distance trade routes in the Mediterranean Basin during the Mesolithic period (25,000 years ago)?

As small groups of hunter gatherers expanded over the landscape behind the retreating ice and tundra, they made sure they knew where to find other groups. The earliest trade would have been in superior flint, obsidian, furs, jade and finely worked stone and bone tools passing from group to group.

The Neolithic Expansion

Neolithic Expansion

The Neolithic expansion that started in Anatolia about 11,000 BC would not have been possible if groups of farmers had not kept in touch with each other, trade goods now included surplus grain and other vegetables as well as brides and grooms and livestock driven over what would become established drovers routes. Ideas, concepts, even religions, were transmitted over the trading routes.

Short Range Coastal Routes

Meanwhile, humans had taken to the water. At first, during the Mesolithic, to fish, but then simple canoes were used to carry trade goods on short journeys up and down the coasts. There are some areas of the Mediterranean that favour maritime startups over others. Those are the places where there is an abundance of safe havens, islands, large and small, within sight of the mainland and each other. It only takes a glance at a map of the Mediterranean to identify those areas. The Aegean Sea, the Greek islands, and, to a lesser extent, the north eastern part of the Adriatic Sea.

By the time the Neolithic had spread to the northern shores of the western Mediterranean, people were using canoes and simple sewn planked boats to move themselves and all the tools and seeds they needed to establish new farming colonies down the coasts. By this stage any coast with decent, sheltering bays was fair game.

In 1989, five canoes, all over 7,000 years old, were discovered in a lake village called La Marmotta, just north of Rome. The lake village is on the edge of Lake Bracciano, about 32 kilometres from the Tyrrhenian Sea. The five canoes are the oldest boats ever found in the Mediterranean, and among the ten oldest known in Europe. Radiocarbon dating placed their origins between 5700 and 5100 BC. One of the most exciting finds has been wooden T-shaped objects, drilled with two to four holes, that explain how the canoes were outfitted to carry large loads. The structure suggests the boats were towed using rope, allowing for the movement of goods, people and animals.

Towing canoes would have allowed these early Neolithic people to transport larger amounts of goods than if they tried to put all their possessions in one boat.

Coasts with long, flat, featureless littorals, such as the coast of North Africa, were avoided. So, whereas the development of societies that lived on the west, north and east coasts of the Mediterranean was hugely influenced by the sea, the development of those that lived in North Africa was influenced by the desert. It is not surprising that their historical trajectories took off in different directions.

Bronze Age Maritime Trade Routes: Sailing Technology and Expanding Networks (3500-1200 BC)

Bronze Age International Trade

About 3500 BC, the first sailing boats were moving up and down the river Nile. They could be larger, carry more food and water for the crew and, most importantly, more cargo than rowed craft. It was to be another two thousand years before the sailing ship became a regular feature in the Mediterranean Sea.

Where did the earliest significant sailing activity in the Mediterranean originate, and how did it spread westward?

Mariners started to make longer voyages. And where did all this new nautical activity start? You guessed, the eastern Mediterranean; within view of those emerging civilisations and Empires in the Middle East.

The Aegean adopted sailing ships early in the 2nd millennium BC. A few centuries later they had arrived in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It took a little longer for sail to reach the central and western parts of the Mediterranean.

What evidence exists for Phoenician sailing vessels in the western Mediterranean, such as the La Laja Cave findings?

It is even possible that the depiction of Phoenician sailing vessels on the La Laja Cave walls at Jimena de la Frontera in southern Spain were the first sightings of sail in that area, between 1150 and 850 BC.

Understanding the development of local coastal trading routes and their role in facilitating long-distance trade in the Mediterranean.

By the time the first sailing boats slipped into the Mediterranean there was a huge amount of activity on the water. Generally speaking, the degree of activity was higher in the eastern Mediterranean, moderate in the central parts and less so in the west. Even so, ostrich shells and ivory from Africa had been arriving in southern Spain since the Copper Age.

All over the Mediterranean, swarms of small boats were taking freight from one place to another; they were the local coastal trading routes that allowed produce to travel enormous distances hand to hand, or rather boat to boat. Admittedly, over an extended period of time, it wasn't quite like Amazon or DHL.

The land routes met with the sea routes at favoured places and by 1000 BC, the Phoenicians, Egyptians and Greeks were building havens in natural enclaves on the coast to protect their trading craft.

How did the Egyptians, Minoans, and Phoenicians establish early maritime trade routes in the 3rd millennium BC?

The earliest known maritime trade routes in the Mediterranean date back to the 3rd millennium BC, when the Egyptians established short range trading networks with the Levant to feed an ever more avaricious line of pharaohs. They were closely followed by the Minoans of Crete who established longer distance trading networks with other Aegean civilizations. No surprise there, the Aegean was the most favoured spot in the Mediterranean for nautical startup ventures.

The sheltered havens, long known to the local mariners were soon found by the foreigners who arrived off the shores. The most favourable of those havens became the regular ports for the sailing boats. The sailing boats seamlessly plugged themselves into the local coastal trade. Goods from even further afield were brought in bulk and distributed out to the smaller craft, crewed by locals familiar with the vagaries of the local area, who then carried the freight up and down the coast.

Once at their final destination ashore, the cargo passed into the labyrinth of tracks and paths to be carried by traders further into the hinterland. Each item increased in perceived value the further it went from its source.

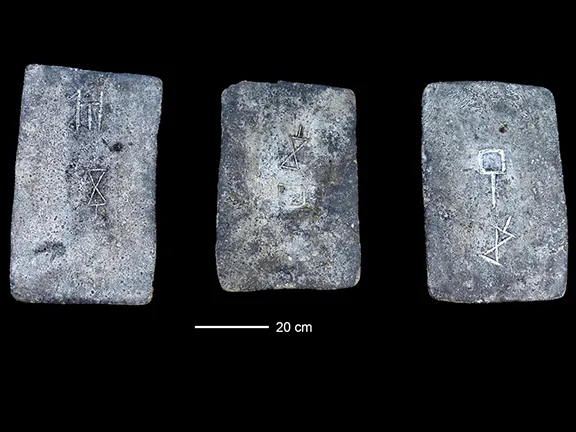

Exploring the significance of shipwrecks like the Dokos, Uluburun, and Gelidonya for understanding ancient Mediterranean trade.

It is inevitable that there would be disasters, boats were overcome by storms and pirates. The oldest wrecks so far discovered are the Dokos wreck dating to 2200 BC, discovered off the island of Dokos in southern Greece, and the Uluburun and Gelidonya, both found in Turkish waters in the eastern Mediterranean, dating back to about 1305 and 1150 BC respectively. Their cargoes and the cargoes of all the wrecks that followed, about 1,780 so far discovered dating before 1500 AD, are starting to give us a much better idea of how and what goods were being transported around the known world.

What does the 2024 deep-water shipwreck discovery off Israel reveal about long-distance voyages in the Late Bronze Age?

All the wrecks mentioned above were found in relatively shallow water, close to shore, indicative of the coast hopping nature of the voyages undertaken at that time. In 2024, a shipwreck was found in deep water 90 kilometres off the Israeli shore. The Canaanite jars recovered from the wreck are thought to date to about 1300 BC. Whilst nowhere near the oldest shipwreck in the Mediterranean Sea, it is important as an early example of a long distance marine voyage well out of sight of land.

Maritime Trade Routes and Traders

Maps are essential; however, they can be misleading.

How should we interpret ancient Mediterranean trade maps and understand the complexities of trade routes?

The arrows only indicate a direction of travel, not a route. How a particular item went from A to B may well have been a convoluted journey with a number of stopovers and even with more than one vessel involved. It should not be forgotten that for a commodity to traverse any route, the journey may well have involved some of the myriad small boats that serviced the larger ships.

Why is it more accurate to consider ancient maritime powers like the Minoans and Phoenicians as establishing areas of influence rather than fixed trade routes?

It is perhaps better to think of the Minoans, Phoenicians, et al as establishing areas of influence, rather than trade routes.

Understanding the multi-national nature of maritime trade in the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean.

By the late bronze age, around 1250 BC, it becomes increasingly more difficult, due to the international nature of maritime trade in the eastern Mediterranean, to differentiate between ships of different nations. A ship in 1250 BC could easily have been built in Cyprus, be owned by a Phoenician, be crewed by a miscellany of Levantine and Aegean nationalities, be carrying a Syrian merchant passenger, and be trading between Anatolia and Egypt.

The Trans-Gibraltar Strait Trade: Evidence of Early Neolithic Connections (3400 BC)

The evidence is mounting that, sometime before 3400 BC, Neolithic people were communicating across the Gibraltar Strait between Iberia and north Africa. Although long suspected and speculated, this obvious, short range sea passage, never out of sight of land, has not yet been sufficiently proved.

What archaeological evidence supports the existence of trade across the Gibraltar Strait between Iberia and North Africa before 3400 BC?

Recent excavations and analysis of artefacts found at Oued Beht in the Maghreb in Morocco have re-sparked interest in this route.

Analyzing the findings at Oued Beht (Morocco) and their implications for understanding early trans-Gibraltar trade.

The farming community at Oued Beht dates from about 3400 BC to 2900 BC. Those people had the full Neolithic package, barley, wheat, peas and goats, sheep, pigs and cattle, mirroring the package found on the northern shores of the Strait, in Iberia. Furthermore their pottery style was very similar to that of the Perdigoes (southern Portugal) and La Loma (near Granada) copper age sites in Iberia, as was the silo technology they used to store grain.

How do artifacts from Valencina de la Concepción and Los Millares (Spain) demonstrate trade with North Africa?

At the copper age sites of Valencina de la Concepción, near Seville in Spain, and Los Millares near Almeria, north African ivory and ostrich shell artefacts have been identified.

What does genetic analysis reveal about the movement of people and culture across the Gibraltar Strait?

Finally, over the last few years, genetic analysis has revealed a southern Iberian population of local hunter-gatherers, Neolithic Iberian farmers and, crucially, Saharan pastoralists. Reinforcing this research, an individual of African descent was buried at the late copper age site of Camino de las Yeseras in the central Iberian massif about 500 kilometres from the sea.

There is little doubt now that a trans Gibraltar Strait route was in operation from the early Neolithic period.

Egyptian Maritime Trade Empire: From the Nile to the Far Reaches of the Mediterranean (2600-30 BC)

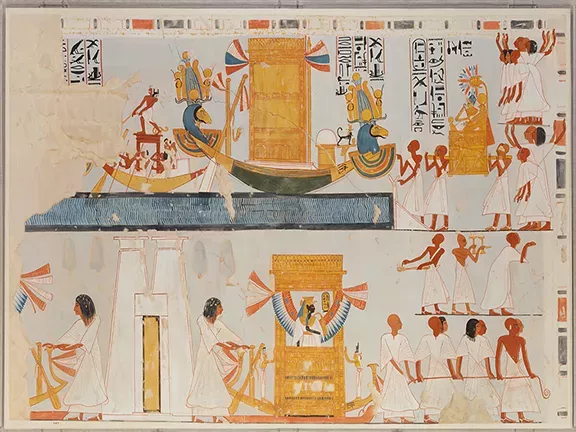

In Egypt, the river Nile had been used by, initially, reed boats and then, after 3500 BC by cross hull lashed boats made from cheap woods such as sycamore, tamarisk and acacia.

How did the Egyptians develop their maritime technology, including the use of sailing ships and stone anchors?

About 3200 BC depictions of river boats with a square sail set on a mast in the forward part of the ship started to appear. By 2475 BC, the Egyptians had seagoing ships with bipod masts, long oars for steerage and heavy stone anchors.

What was the significance of the "Byblos ships" in Egyptian trade with the Levant?

Overseas trade to obtain the many exotic goods not available in Egypt such as cedar wood, silver, resins, fruits and oils accelerated with the consolidation of the Old Kingdom. About 2600 BC, the pharaoh Sneferu sent a fleet of forty ships to the Lebanon for a cargo of cedar wood. Egyptian ships began to ply up the Levantine coast, at least as far as Byblos. In fact a 'special relationship' developed between Byblos and Egypt as early as 2686 BC. Byblos became the focus of exotic goods from the north and east and, most importantly, wine. Egyptian gold ensured that much of these exotica arrived in Egypt. This small coastal town is mentioned many times in Egyptian records and was even accorded a special role in Egyptian cosmology. The ships engaged in this Levantine trade became known as 'Byblos ships'.

Egypt's trade with the Land of Punt and the routes through the Wadi Hammamat.

From about 2500 BC, Egypt also traded with the Land of Punt, located in northwest Eritrea via the Wadi Hammamat, a dry river bed that ran from Thebes, east, to the Red Sea. Punt produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory and wild animals.

How did the Ptolemaic dynasty and the establishment of Alexandria impact Egyptian maritime trade?

The Egyptian pharaohs from the Old Kingdom on, became masters of the art of forming trading networks with other societies and civilisations, through marriage, trade treaties or just straight forward military acquisition. Egypt continued maritime trading on its own account, often state controlled, until the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC (with the rider that the ships may not have been owned or crewed by Egyptians). Trade to and from Egypt reached its apex under the Ptolemaic dynasty (332 - 30 BC) following the establishment of Alexandria that then became the centre of trade between Egypt and China, Asia, northern Europe and the Orient.

The Cetinians and Early Adriatic Trade: Connecting the Central Mediterranean (2300-2000 BC)

Cetina Area of Influence

The Cetina people were based near the mouth of a river with the same name that runs from the metalliferous hinterland into the Adriatic near the city of Split, within view of a spread of islands extending towards southern Italy.

Who were the Cetinians, and what role did they play in early Adriatic and Mediterranean trade?

They appeared about 2300 BC and rapidly extended their influence throughout the Adriatic, into southern Greece and Italy and out into the Mediterranean as far as Sicily and Malta. The Cetina traders, in their small coastal craft, were the catalysts that brought together a diffuse range of products in diverse locations whose presence had proved not a little mysterious, and helped explain similarities in pottery, cremations and figurines throughout the region.

Analyzing the diverse range of trade goods associated with the Cetinian network: faience necklaces, copper daggers, and bone plaques.

And what an eclectic mix of trade goods have so far been identified; necklaces of faience, ostrich egg and fish bone implements, copper daggers and axes, and bossed bone plaques (carved in Sicily and found as far afield as Malta, Lerna and Troy).

What do the engravings at the Tarxien temple (Malta) suggest about Cetinian boat designs?

It may even be that a depiction of their boats exists in the early engravings at the temple in Tarxien, Malta, where a record of the type of boat seen off the island from prehistoric times to the modern day are recorded for posterity in the form of 'ship graffiti' by unknown artists.

Although short lived, this trade network seems to have evaporated by the start of the second millennium BC, it looks as though the Cetina traders made the first connections between the Adriatic and the central Mediterranean.

Minoan Maritime Networks: Dominance in the Aegean and Beyond (2000-1750 BC)

Minoan Area of Influence

Chronologically, the Minoan maritime network came after the Cetinian network. In reality, the two probably crossed paths.

How did the Minoans leverage their strategic location and advanced shipbuilding to establish a vast maritime network?

The Minoan success was due in part to their strategic location on the island of Crete, which gave them easy access to both the eastern and western Mediterranean. The Minoans also had a number of technological advantages, including advanced shipbuilding techniques and navigational skills. The Minoans were skilled seafarers and traders, and their ships travelled throughout the eastern and central Mediterranean Sea from the 3rd millennium BC until the 15th century BC, ending only with the collapse of the Minoan civilization.

What goods did the Minoans trade, and with which civilizations did they interact?

The Minoans traded a wide variety of goods, including olive oil, wine, pottery, textiles, and metals.

The Minoans were particularly interested in trading with the emerging civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean, such as those in Egypt and the Levant. They also traded with the civilizations of the central Mediterranean, such as the Mycenaeans and the Bronze Age societies, the forebears of the Etruscans, in the northwestern parts of the Italian Peninsula.

The Minoan maritime trading presence was essential to the success of their civilization. It allowed them to access essential resources, such as metals and obsidian, which were not found on Crete. It also allowed them to spread their culture and influence throughout the Mediterranean world.

Their influence was wide. Minoan pottery has been found at archaeological sites throughout the Mediterranean Sea, including Egypt, Cyprus, and Greece and Minoan ships have been depicted in Egyptian and Mesopotamian art.

Minoan traders established trading colonies on islands throughout the Aegean Sea and had a strong relationship with the Mycenaeans; they traded goods with each other extensively.

The Mycenaeans c 1750 - 1050 BC

Mycenaean Area of Influence

The Mycenaeans evolved as a distinct civilisation on mainland Greece after about 1750 BC. The Minoan traders heavily influenced their culture. Several centres of power emerged in southern Greece, the most important of which became Mycenae.

The Mycenaean centres gradually increased contact with the outside world, especially with the Cyclades and the Minoan centres on the island of Crete. Mycenaean presence appears to be also depicted in a fresco at Akrotiri, on Thera Island, which possibly displays many warriors in boar's tusk helmets, a feature typical of Mycenaean warfare. In the early 15th century BC, commerce intensified with Mycenaean pottery reaching the western coast of Asia Minor, including Miletus and Troy, Cyprus, Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt.

What evidence exists for Mycenaean settlements and trade in places like Miletus, Cyprus, and Sardinia?

The Minoan civilisation declined after 1500 BC which gave the Mycenaeans the opportunity to expand their influence into the Aegean Sea. About 1450 BC, they took over the Minoan homeland, Crete and colonized several Aegean islands, including Rhodes. The trade routes were expanded further, reaching Cyprus, Amman in the Near East, and Apulia in Italy.

Mycenaean pottery has been found in the Antigori Nuraghe on Sardinia mixed with locally produced ceramics dated to between 1300 and 1150 BC.

Excavations at Miletus in southwest Anatolia indicate the existence of a Mycenaean settlement there from about 1450 BC, replacing a previous Minoan settlement. This site became a sizable and prosperous Mycenaean centre until the 12th century BC.

Phoenician Maritime Trade: Establishing Colonies and Networks Across the Mediterranean (1550-650 BC)

Phoenician Area of Influence

The Phoenicians were skilled seafarers and traders, and they established trading colonies all along the Mediterranean coast, from North Africa to Spain.

How did the Phoenicians become the most successful trading nation in the Mediterranean before the Romans?

From small beginnings, conveying cedar wood to Egypt to build a temple at Heirakonpolis between 3500 and 3200 BC, they grew to become the most successful and well known trading nations in the Mediterranean before the arrival of the Romans. They traded a wide variety of goods, including metals, textiles, wine, and olive oil.

Their trading network connected the Phoenician homeland in the Levant (modern-day Lebanon and Syria) with Phoenician colonies and trading partners throughout the Mediterranean.

How did the rise of Carthage and Greek competition impact Phoenician trade?

After 650 BC, the Carthaginians started to compete for territory with their compatriots. It was the start of the end for the Phoenicians who were already facing competition from Greek traders in the eastern Mediterranean.

Revisiting the 2024 deep shipwreck, and the light it sheds on Phoenician seafaring capabilities.

In 2024, the discovery of what may turn out to be the oldest and deepest shipwreck so far discovered in the Mediterranean Sea gave new insights into how far from shore late Bronze Age mariners were prepared to sail.

Hundreds of intact amphorae - ancient storage jars - believed to be 3,300 years old, were discovered on the sea bed, 90 kilometres off the northern coast of Israel at a depth of 1,800 metres.

Experts at the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) say the discovery suggests sailors of the period were able to navigate the oceans by using celestial navigation, taking bearings from the sun and stars.

Only two of the jars were brought up to the surface, a process that required special equipment to avoid damaging them or any other artifacts around them. The jars, believed to have belonged to the ancient Middle Eastern Canaanite people, in other words, the people we now call the Phoenicians, who lived along the Mediterranean's eastern shores, will be displayed from the summer of 2024, in Jerusalem's National Campus for the Archaeology of Israel.

The IAA said the wrecked vessel, buried under the muddy seafloor with hundreds of the jugs jumbled on top, appeared to have been 39 to 45 feet long. It said both the boat and the cargo appeared to be fully intact.

Greek and Etruscan Maritime Trade: Competition and Cultural Exchange (750-320 BC)

The emerging and competing civilisations in the Near East created a market for all sorts of goods that, until the 8th century BC had been satisfied first by the Minoans, then the Mycenaeans and then by the Phoenicians. In the 8th century BC, the Greeks decided to get in on the act.

How did the Greeks establish their maritime trading presence in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions?

The Greek maritime trading presence peaked in the 5th century BC, during the Golden Age of Athens, and declined in the 4th century BC, with the rise of Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic kingdoms. However, the Greeks continued to trade in the Mediterranean throughout the periods of the Roman and Byzantine Empires.

The Greek trading network concentrated on their colonies in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions. In the Mediterranean, they penetrated west as far as Empuries in Spain. They traded in a wide variety of goods, including grain, wine, olive oil, pottery, and metalwork.

The Etruscans c 600 - 384 BC

The Villanovan culture, the predecessor to the Etruscan civilization, emerged in western central Italy between 1000 and 750 BC. The Villanovans prospered from the region's rich mineral deposits, which included lead, tin, copper, silver, and iron. Agriculture also developed, with metal implements improving productivity. This stability allowed for the development of small-scale manufacturing industries, producing pottery and metal goods. Trade took place between Villanovan towns, especially those on the coast and near rivers. Bronze works discovered at Villanovan sites indicate contact with Sardinia, central Europe, the Balkans, and even the Cyclades. These links brought about more advanced metallurgy, but the flowering of Etruscan trade was still to come.

Understanding the role of Etruscan emporia like Pyrgi, Regae, and Gravisca in facilitating trade.

By the 8th century BC, the Etruscan manufacturing industry was booming thanks to a ready supply of raw materials, further benefited from the arrival of artists and craftsmen from Greece and the Levant. These foreign artisans and traders set up shop in Etruria to meet the demand for precious metal goods and fine pottery. Many established themselves in specialized coastal trading area, colonies, where they could live as they wished, protected by their sanctuaries and able to worship their religion. The most important colonies were Pyrgi (a port of Cerveteri), Regae (Vulci), and Gravisca (Tarquinia). These colonies ensured a continuous supply of luxury goods for the Etruscans, for everyday use, as votive offerings at sanctuaries, or to be buried with the dead in the large painted tombs of the Etruscan elite.

Given the multi ethnic nature of the Etruscan colonies and the diverse trade from other countries and the undoubted presence of trading ships from other maritime trading nations, it may be correct to use the term emporium after the 6th century BC despite the fact that these emporia are situated within the home territory of the Etruscans.

The Etruscan civilization flourished in central Italy from the 8th to the 3rd century BC. Its prosperity was largely based on trade, both within Etruria and with other Mediterranean civilizations. The Etruscans were especially known for their production and export of iron, but they also traded other goods such as pottery, wine, and olive oil. In exchange, they received ivory from Egypt, amber from the Baltic, and pottery from Greece and Ionia.

The Etruscans did not form a cohesive political and economic state, but rather a network of independent cities. Each city had its own trade arrangements and specialized in different goods. For example, Cerveteri was known for its goldwork, Tarquinia for its pottery, and Populonia for its metalworking.

Goods were bartered and paid for in kind, although bronze ingots and coinage were also used. Coastal towns such as Cerveteri, Tarquinia, and Populonia acted as emporia, where goods from inland Etruria were traded with goods from other parts of the Mediterranean.

The Etruscan trade network helped to spread Etruscan culture and influence throughout the Mediterranean region. Etruscan art and artifacts have been found in Greece, the Phoenician city of Carthage, and even Egypt.

By the 6th century BC, Etruscans were exporting a wide range of goods, including grain, pine nuts, olive oil, wine, stone sculpture, bronze cauldrons, marble, wood, goldwork, pottery, horse bits, and inlaid ivory plaques. Etruscan artisans produced high-quality goods that were in high demand throughout the Mediterranean world.

Etruscan exports were found as far away as Greece, Carthage, Egypt, and Spain. Etruscan wine was particularly popular, and Etruscan bucchero pottery was prized for its distinctive black gloss finish. Etruscan manufactured goods were also used as votive offerings at important religious sites such as Olympia, Delphi, and Dodona.

How did competition from the Greeks and Carthaginians impact Etruscan trade and political power?

An increase in competition from Greek and Carthaginian traders drove the Etruscans to look for new markets inland. They found success in the Celtic lands north of the Alps, where they exported wine and other goods.

The Etruscans faced stiff competition from other trading cultures, such as the Greeks and Carthaginians. In 509 BC, Etruscan cities signed a treaty with Carthage to agree on exclusive areas of operation, but they still had to defend their interests against Greek naval fleets. In 540 BC, a combined Carthaginian/Etruscan force defeated a Greek fleet at the Battle of Alalia also known as the Battle of the Sardinian Sea. Some versions of this battle have the Greeks winning but suffering such losses that it severely compromised their own maritime trading empire. However, in 474 BC, the Etruscans suffered a naval defeat at the hands of a combined Syracusan and Cumaean fleet at the Battle of Cumae.

In 384 BC, the Syracusan tyrant Dionysius I attacked the Etruscan coast and destroyed many of their ports. This was a major blow to Etruscan trade, and it contributed to the decline of many Etruscan cities in the 4th century BC onwards. The Etruscans also faced competition from the emerging power of Rome. By the late 4th century BC, Rome was beginning to flex its muscles in the region and expand its control over trade routes. This further contributed to the decline of Etruscan trade and power.

Carthaginian and Roman Maritime Dominance: From Punic Wars to Imperial Networks (650 BC - 202 AD)

The Carthaginians, who were based at Carthage, a Phoenician colony in North Africa, became a major maritime power in the 6th century BC. They controlled the trade networks in the western part of the Mediterranean, taking over trading posts and colonies from the Phoenicians. The Phoenician networks in the eastern Mediterranean were largely taken over by the Greeks.

It all came crashing down for the Carthaginians in 202 BC, after the Second Punic War when Rome began to dominate the Mediterranean.

The Romans after 202 BC

The Romans created the largest network of maritime trading routes yet seen connecting all corners of the Roman Empire, from Britain in the north and Spain in the west to Egypt and Syria in the east. The Romans traded in a wide variety of goods, including grain, wine, olive oil, pottery, textiles, and spices.

The Human Element in Ancient Maritime Trade: Ship Ownership, Crewing, and Profit

Although the maritime routes are described as Minoan, Phoenician, Greek and so on, this probably gives the wrong impression. It is highly unlikely that any one long distance sailing vessel was built, owned, and crewed by people from one society or nationality. The impetus to extend trading routes may have begun as a policy introduced by a ruling elite of a particular society to enable them to obtain exotic, rare or even necessary goods and/or bolster up their own position within their society, but the implementation of that policy was left to others. Ships were bought or borrowed from other countries as well as built in house as it were.

The Phoenicians were master shipbuilders and seafarers. Their ships were bought by the Greeks, Romans and even the ancient Egyptians to enable them to extend their own trading networks. They were likely crewed by sailors who hailed from every part of the Mediterranean, each trading post would have been a polyglot of nationalities with crews being discharged and new crews coming aboard, just as happens to this day.

Perhaps a more important question would be; 'Who benefits from a particular voyage?' The obvious answer is; 'Whoever commissioned the boat'. Certainly he, or she, would benefit by way of taxes on the cargoes, freight charges or direct ownership of some of the cargo. It is unlikely that the regular gauloi (round ship - referring to the shape of the hull), the Phoenician equivalent of the tramp steamer, ever carried a cargo owned by just one merchant. An intriguing find on the Cape Gelidonya A shipwreck that went down between 1200 and 1150 BC off the southern coast of Anatolia, was a cylinder seal once owned by a Syrian merchant. Was he keeping an eye on his goods?

It is known that the Phoenicians and later the Carthaginian traders paid tribute to their home city state, most often Tyre, from the profits of their voyages.

In fact, excavation of ancient shipwrecks such as that discovered at Uluburun, shows that the cargo itself is often from diverse sources, obviously picked up at different places and destined for various ports. The captain and perhaps crew members are likely to be the direct beneficiaries of such entrepreneurial voyages.

The situation was very fluid and each voyage would have been, in its own way, unique.

Amarna Archives

Wrecks are not the only places to find evidence of commerce and how it was managed. Interstate communications via emissaries and letters can be traced back to the early 2nd millennium BC. Occasionally those letters have survived and reveal a whole treasure trove of goods being shipped from one place to another.

How do the Amarna letters provide insight into ancient interstate communications and trade practices?

One example is the Amarna archive. Written in Arkadian on clay tablets that were then sealed in clay envelopes, the over 300 letters span a period of about 30 years commencing 1360 BC. The archive contains a wealth of information about cultures, kingdoms, events and individuals in a period from which few written sources survive.

These tablets shed much light on Egyptian relations with Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Canaan, and Alashiya (Cyprus) as well as relations with the Mitanni, and the Hittites. Although primarily diplomatic exchanges between potential, and at times real, enemies, in fact the first recorded examples of official diplomacy, they also reveal what was on the move around the eastern Mediterranean, to be sure between the kings and the elite of society on ships such as the Uluburun wreck, rather than the humdrum cargoes for more normal mortals such as those carried by the Gelidonya wreck.

Top of the list were princess brides, craftspeople, physicians, augurs and other ritual experts, given as presents or on loan. With these high demand individuals moved huge quantities of wealth goods either as raw material or as finished goods. The goods were specified as greeting gifts to accompany letters of exchange, bride dowries or as a result of an obsequious request, such as this beautiful exchange between Burna Buriash II of Babylon and Amenhotep IV of Egypt.

And, as I am told, in my brother's country everything is available and my brother needs absolutely nothing; also in my country everything is available and I myself need absolutely nothing, however.' and there followed a request for a large amount of gold (said by foreign rulers to be as -'plentiful as dust.' in Egypt).

The most common commodities mentioned in the Armana letters were gold, silver, lapis lazuli, ivory, Sudanese blackwood, snow-white Egyptian cotton, wool and various precious and semi precious stones. The latter often carved into delicate vessels to contain scented oils. Decorated furniture, horses, chariots and weapons all appear in the cargo lists. Commodities such as tin, copper, cedar, glass, pottery and faience seemed not to be worth royal attention.

Mentioning diplomacy, there are some wonderful and amusing extracts that offer an insight into royal life at that time: a request for an Egyptian princess with the codicil that any female that could pass as one in Babylon would suffice; a complaint that a chariot given as a present to a Great King, had been put on display at Armana alongside tribute from a vassal.

For anybody interested, I can recommend 'The Amarna Letters by William L. Moran (1992)'. It is the most comprehensive English translation of the Amarna archives to date. It includes all 380 known letters, as well as Moran's commentary and notes.

References

General Mediterranean Trade and Early Civilizations:

Abulafia, D. (2011). The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Oxford

This comprehensive work provides a broad overview of Mediterranean maritime history, covering the civilizations mentioned (Minoans, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans).

Horden, P., & Purcell, N. (2000). The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Blackwell.

This book focuses on the interconnectedness of Mediterranean societies and the importance of maritime trade in shaping their development.

Braudel, F. (1972). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Harper & Row.

Although focused on a later period, Braudel lays out the long term geographical and historical factors that shaped Mediterranean trade.

Sherratt, A., & Sherratt, E. S. (1993). The growth of the Mediterranean economy in the early first millennium BC. World Archaeology, 24(3), 361-378.

This source discusses the economic growth and trade networks of the early first millennium BC.

Early Maritime Activity and Neolithic Expansion:

Alessia Arnoldus-Huyzendveld, et al. (2022). The 7000-year-old waterlogged village of La Marmotta (Italy). Antiquity, 96(387), 606-624.

This is a primary source for the La Marmotta canoe findings.

Broodbank, C. (2000). An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge University Press.

Discusses the early maritime activity in the Aegean.

Runnels, C. (1995). Review of Aegean Prehistory IV: The Stone Age of the Aegean from 7000 to 3000 BC. American Journal of Archaeology, 99(4), 699-720.

Provides context for the Neolithic expansion and early maritime activity.

Specific Civilizations and Trade Routes:

Markoe, G. E. (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press.

Details the Phoenician maritime trade and expansion.

Cline, E. H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press.

Discusses the late Bronze Age trade networks and their disruption.

Ridgway, D. (1992). The Etruscans. Blackwell Publishers.

Explores Etruscan trade and maritime activity.

Hadjisavvas, S. (1991). Olive Oil Processing in Cyprus: From the Bronze Age to the Byzantine Period. Paul Astroms Forlag.

This provides information about trade goods, such as olive oil.

Van de Mieroop, M. (2007). A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 BC. Blackwell Publishing.

Provides context for Egyptian and Levantine trade.

Yasur-Landau, A., et al. (2024). A Deep-Water Late Bronze Age Shipwreck off the Carmel Coast, Israel. Journal of Nautical Archaeology (forthcoming).

This is the primary source for the 2024 Canaanite shipwreck discovery.

Trans-Gibraltar Strait Trade:

Diaz-del-Rio, P., & Garcia-Sanjuan, L. (2012). The archaeology of the Atlantic facade: studies of the Mesolithic and Neolithic from the Iberian Peninsula to the Sahara. Archaeopress.

This provides context for trade and cultural exchange across the Gibraltar Strait.

Schuhmacher, T. X., et al. (2020). Genomic Differentiation and Holocene Migrations of West African Pastoralists. Current Biology, 30(19), 3762-3773.e6.

This source covers the genetic evidence of Saharan pastoralist presence in Iberia.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution