Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

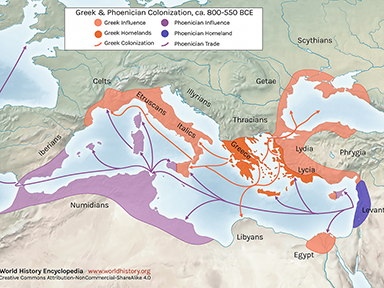

Ancient Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

A brief look at the ancient overland trade routes such as the Spice Road, Royal Road and Silk Road, that connected the whole of the known world with the Mediterranean by the end of the 1st millennium BC.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-09-20 | Last Updated 2025-10-12 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 23,593 times

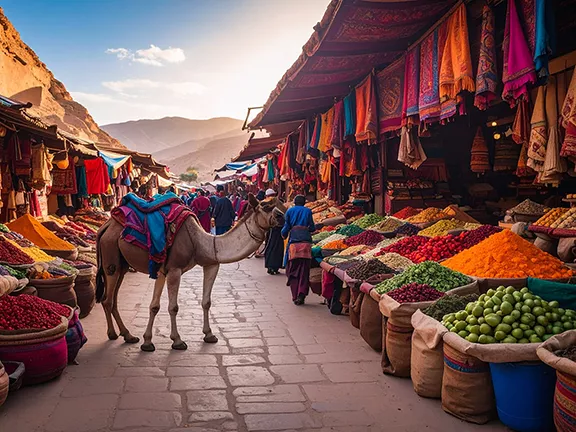

Camal caravan in the Sahara Desert

The Overland Routes

To complete our understanding of the movement of commodities around the Mediterranean, we also need to take a brief look at the overland routes that had already been established by the 1st millennium BC.

Drovers Routes to Neolithic Markets

The origin of the land-based routes is lost in the mists of time. Mesolithic communities wore tracks across the landscape linking their communities together, as did the later Neolithic people. Those tracks often developed into more substantial drover's routes as the Neolithic herders moved cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats across the land, from winter pastures to summer pastures, to recognised centres where they could trade breeding stock and surplus animals for meat for pottery, beer and more exotic goods that came from afar. The first markets in effect.

Signs of Trading – the Obsidian Atomic Footprint

The historian Colin Renfrew researched obsidian finds in the Middle East dating back to about 6000 BC using what is known as the obsidian atomic footprint. He found that the number of finds fell off dramatically the further those finds were from the source of the obsidian, an obvious sign of trading rather than dedicated expeditions to find and bring back obsidian. For instance, there are two obsidian sites in Armenia. The obsidian found its way to Mesopotamia. Renfrew found that, at a site 250 miles from the source, about half the chipped stones at the site was obsidian whilst at another site, 500 miles from the source, only two percent of the chipped stone was obsidian.

The First International Overland Trade Routes

As communications across the Mediterranean improved and societies started to develop, amber, spices, slaves, precious metals, and ever more exotic goods became more in demand and entrepreneurs forged links with the Far East, central and West Africa, Asia, and northern Europe. This was the beginning of the overland routes that became named and famous.

Donkeys, the first ‘Ships of the Desert’

The desert routes would not have been practicable without that first 'ship of the desert', the donkey. Donkeys evolved in northeast Asia from the wild ass in the early part of the 4th millennium BC. The impetus coming from pastoralists needing a beast of burden to carry products over an ever drier landscape.

In 3000 BC, or thereabouts, ten donkeys were buried beside a royal enclosure at Abydos. Five hundred years later, a donkey was worth four times that of a normal slave. Donkeys are able to carry 50 - 90 kilogrammes over a distance of 30 - 50 kilometres per day. They can survive on the roughest vegetation and can go without water for several days. The donkey marked the first improvement over human portage. Although not happy crossing expanses of true desert, the donkey is nimble footed and at home in the semi-arid environments of the Mediterranean. Not surprising then that they were soon a common sight all over the Middle East.

Until the domestication of the ultra hardy one humped camel, also known as the dromedary, in the early 1st millennium BC, the donkey was the preferred beast of burden.

Apart from the Amber Road, none of the overland roads traversing desert and semi-arid zones would have been fully developed without the donkey and the camel.

Although known as Roads, the word Route is probably more accurate since all the roads had multiple tracks leading in the same general direction but taking in different population centres.

The Copper Route

The earliest formalised trade route we know of brought copper from Anatolia to the emerging Sumerian civilisation in southern Mesopotamia.

Shortly after 4000 BC, the Ergani mines in Anatolia began to ship copper to Uruk, about 750 kilometres away, down the River Euphrates. In return, the fertile lands of Mesopotamia sent grain to Anatolia. This route was superseded after about one thousand years when copper ore deposits were found in the Persian Gulf area in the land of Magan, present day Oman.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Amber Road

The Amber Road by DI Richard Resch

The Amber Road was an ancient trade route for the transfer of amber from coastal areas of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Prehistoric trade routes between Northern and Southern Europe were defined by the amber trade. It was one of the longest trade routes in the ancient world, stretching over 4,000 kilometres.

Neolithic use of Amber

The Amber Road was first used in the Neolithic period, around 3000 BC. Evidence of amber trade from the Baltic Sea to southern Europe has been found in archaeological sites throughout Europe and the Middle East including the breast ornament of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun (roughly 1300 to 1346 BC.)

Amber during the Bronze and Iron Ages

The Amber Road became increasingly important during the Bronze Age and Iron Age, as amber became a highly prized commodity in the Mediterranean world. Amber was used to make jewellery, ornaments, and other luxury goods. It was also believed to have magical properties.

The Romans and Amber

The Amber Road reached its peak during the Roman Empire. The Romans were particularly fond of amber, and they traded for it extensively with the Germanic tribes of northern Europe. The Romans built a network of roads and fortifications along the Amber Road to protect their trade routes.

The Amber Routes

As an important commodity, sometimes dubbed "the gold of the north", amber was transported from the North Sea and Baltic Sea coasts overland by way of the Vistula and Dnieper rivers to Italy, Greece, the Black Sea, Syria, and Egypt over a period of thousands of years.

The exact routes of the Amber Road varied over time, but it is thought to have passed through modern-day Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey. The Amber Road was not a single road, but rather a network of routes that connected different regions. It was used by a variety of peoples, including the Celts, Romans, and Germanic tribes.

It was a major trade route for thousands of years, and it played an important role in the cultural and economic development of Europe. It facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas between different civilizations, and it helped to spread new technologies and cultural practices throughout Europe.

Decline off the Amber Road

The decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD led to a decline in the use of the Amber Road. However, the trade in amber continued throughout the Middle Ages, and the Amber Road remained an important trade route until the 16th century AD.

Other Trade Goods on the Amber Road

Amber was by no means the only commodity to be taken along the Amber Road. The peoples of the Baltic region all highly prized gold, silver, copper, and bronze. These metals were used to make jewellery, weapons, and other tools.

The Romans were particularly fond of the woollen textiles produced in the Balkans. These textiles were known for their high quality and durability.

Roman wine was also a popular item of trade on the Amber Road. The Romans produced a wide variety of wines, from sweet to dry, and these wines were enjoyed by the peoples of the Baltic region.

Olive oil was another popular Roman product that was traded for amber. Olive oil was used for cooking, lighting, and body care.

Roman glass was also a popular item of trade on the Amber Road. Roman glass was known for its high quality and clarity, and it was used to make a variety of objects, including jewellery, tableware, and windows.

In addition to these products, the Romans also traded for other goods on the Amber Road, such as furs, honey, and wax.

Pottery, vases, and other ceramic objects were also traded for amber on the Amber Road. Ceramics were used to store and transport food, liquids, and other goods.

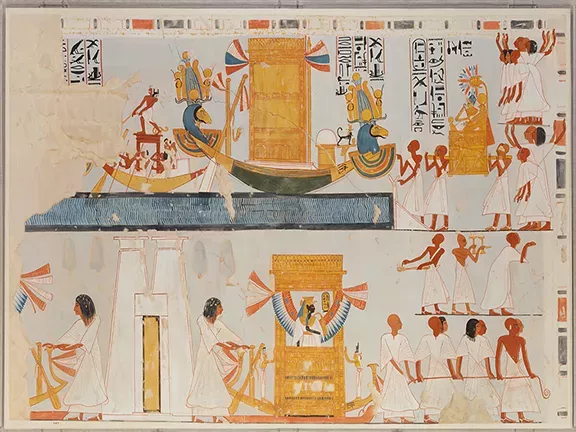

The Ways of Horus

The Ways of Horus

The Ways of Horus is an almost mythical route and is certainly the first to be formalised by the elite of Predynastic Egypt.

Linking Egypt with the Levant

To the east of the delta of the river Nile is a narrow stretch of Sinai desert through the bottleneck caused by the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Gulf of Suez to the south. Another stretch of desert crosses Sinai to Gaza. This dry, rocky, coastal passage backed by dunes and more rocks had been the only land route for goods from the Levant, and even further afield, from northern Mesopotamia, to Egypt since at least 3500 BC. Along that road passed cedar from Lebanon, resins, aromatics and copper, all carried by independent traders in long donkey trains.

Crossing the Sinai Desert

The early rulers of Predynastic Egypt soon realised that the funnel created by the Mediterranean - Gulf of Suez gap allowed them to regulate goods entering and leaving Egypt. The Sinai passage became formalised as a 340 kilometre, 10 day route, 'The Ways of Horus', that ran from the delta as far as modern day Tel Aviv about 3100 BC.

Introduction of the Donkey to Egypt

It was just at this time that the donkey was introduced to Egypt, having evolved from the African wild ass during the early 4th millennium. Donkeys are more suited to the relatively short, rocky routes, such as the Ways of Horus, than the camel that much prefers a sandy trail. Donkey caravans became the preferred mode of transport along the Way and are even depicted on wall plaques in royal tombs. In Akkadian texts, donkeys were worth four times that of a slave.

Controlling the Trade Route

At the southern Levantine end, the Egyptians built stations from which the caravans could be provisioned. They were also handy places for customs officials to monitor the copper, oils and wines entering Egypt from the Levant. In Sinai itself, state sponsored, quasi-military expeditions mined copper and turquoise to haul it down the Way to Egypt.

The Ways of Horus is probably the route taken by the vines and the Eurasian plough that were introduced into Egypt about this time.

To cover all the trails through the Sinai passage, at least five stations were built as shown on the map. En Besor, for instance, was located on the best water spring at the beginning of the Ways.

At various locations along the Ways, royal cartouches (Egyptian) called serekhs have been found together with seals on containers of Levantine design, all testifying to the degree of state control imposed on exports and imports.

Donkeys Replaced by Sail

Sadly, the donkey could not compete with the bulk carrying capabilities of the sailing ship that appeared in the eastern Mediterranean after about 3200 BC. From about 2700 BC, coinciding with the start of the Old Kingdom period in Egypt, trade along the Ways of Horus diminished. A new maritime route from the Nile delta to Ashkelon, Haifa and Byblos now brought bulk cargoes of Lebanese cedar, metals from Anatolia, rare stones and lapis lazuli to feed an ever more avaricious elite establishing control in Egypt. One shipment (using a number of ships) of cedar alone consisted of 12 tonnes of the wood that, during the 26th century BC, built the royal barge of Cheops. The journey by sea corresponding to the same journey along the Ways of Horus, could be accomplished in just two or three days.

New Kingdom Fortress at Tell El-Kharoba

For whatever reason, perhaps the maritime traders were becoming more at risk from pirates, or facing more competition from other maritime powers such as the Mycenaeans, by the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC), the land based Ways of Horus had assumed a new significance. The New Kingdom pharaohs developed the existing infrastructure and established a chain of fortifications along the route, including major sites like Tell Habua, Tell el-Borg, and Tell el-Abyad, to secure their borders and maintain imperial control.

The recent discovery of a massive military fortress at Tell El-Kharoba marks a significant addition to this network, providing new evidence of the scale and complexity of Egyptian military architecture and logistical planning.

The Discovery and Previous Excavations

The recent find, announced in October 2025, is a colossal mudbrick fortress dating to the New Kingdom period. The discovery was made by an Egyptian archaeological mission affiliated with the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) under the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

A smaller fortress structure was previously discovered at the Tell El-Kharoba site during excavations in the 1980s, located approximately 700 metres to the southwest of the new find.

The newly uncovered fortress is estimated to cover an area of approximately 8,000 square metres, making it nearly three times the size of the previously known fortification at the site and one of the largest ever found along the Horus Military Road.

“This discovery is a living testament to the brilliance of ancient Egyptian military architecture,” said Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Sherif Fathy. “It offers a new window into our military history and highlights Sinai’s pivotal role at the crossroads of civilisations.”

Architectural Findings

The excavation has revealed several key architectural features, despite the significant challenges posed by shifting sand dunes.

Defensive Wall: A section of the southern main wall has been uncovered, measuring approximately 105 metres long and 2.5 metres wide.

Defensive Towers: The structure includes multiple defensive features, with at least eleven defensive towers identified to date.

Entrances: A secondary entrance, measuring 2.20 metres in width, has been located in the southern wall. Preliminary studies indicate the southern entrance was redesigned and modified on multiple occasions.

Internal Structure: An unusual “zigzag wall” divides the fortress from north to south, enclosing a residential area designed for the garrisoned soldiers. This distinctive layout reflects the sophisticated engineering and internal organisation of New Kingdom military camps.

Construction Phases: Preliminary studies suggest the fortress underwent multiple phases of restoration and structural modification throughout its period of occupation.

Key Artifacts and Chronology

The artefacts recovered confirm the fortress's dating to the early New Kingdom and its function as a self-sufficient military outpost.

Dating Evidence: Foundation deposits beneath one of the towers and various pottery fragments date the initial construction to the first half of the Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1550–1292 BC).

Royal Connection: A vessel handle was discovered sealed with the cartouche (royal name) of King Thutmose I (reigned c. 1506–1493 BC), establishing a firm connection to the beginning of the New Kingdom empire-building era.

Daily Life & Logistics

Pottery fragments and vessels.

A large bread oven and remnants of petrified dough, confirming food preparation on site.

Imported volcanic stones, believed to have been shipped from the Greek islands, demonstrating the extensive trade and logistical networks supporting the frontier garrisons.

Historical and Strategic Significance

The discovery at Tell El-Kharoba offers some interesting insights into New Kingdom Egypt and the 'Ways of Horus'.

Military Might: It confirms the strategic planning and organisational genius of the pharaohs in establishing an integrated, comprehensive defensive system to protect the eastern borders.

Frontier Control: The fortress's size and strategic location near the Mediterranean coast highlight its crucial role in securing both the land route (Horus Road) and the possible maritime approach to Egypt.

Logistical Hub: The evidence of a residential quarter, food preparation facilities, and imported goods indicates the fortress was a fully operational, self-sustaining hub for the Egyptian military and a significant node in the ancient trade artery.

Later use of the road: Until the discovery of Tell El-Kharoba, it was thought that the Ways of Horus route became less significant after about 2700 BC. Apparently, the road continued in regular use until at least 1500 BC.

Future Outlook

The excavation is ongoing, with archaeologists planning to uncover the remaining sections of the walls and associated internal structures. A primary objective is the search for a possible military harbour believed to have supported the fortress on the nearby coastal area, which would further confirm the fortress's combined land and sea defensive role.

The Incense Road

The Incense Road

The Incense Road was a network of trade routes that connected the Arabian Peninsula with the Mediterranean Sea. It was used to trade incense, perfumes, and other spices. The Incense Road was one of the most important trade routes in the ancient world, and it played a major role in the economic and cultural development of many of the ancient civilizations.

The Incense Road began to develop around 3,000 BC, when the ancient Egyptians began trading for incense from the Arabian Peninsula. The Incense Road flourished during the Roman Empire, as the Romans created a huge market for incense. The Romans used incense in religious ceremonies, funerals, and other public events.

The Incense Road declined in the 5th century AD, with the fall of the Roman Empire. However, the trade in incense continued throughout the Middle Ages, and the Incense Road remained an important trade route until the 16th century AD.

The Salt Road

The Salt Road

The Salt Road was a network of trade routes that connected the Sahara Desert with the Mediterranean Sea. It was used to trade salt, gold, and other goods. The Salt Road was an important trade route in the ancient and medieval worlds.

Salt from the Sahara Desert to Ancient Egypt

The Salt Road began to develop around 3000 BC, when the ancient Egyptians began trading for salt from the Sahara Desert. Salt was a highly prized commodity in the ancient world. It was used to preserve food, flavour food, and make medicine.

The Romans and Salt

The Salt Road flourished during the Roman Empire. The Romans used salt in their food, in their baths, even to pay their legions, hence the word salary, and in religious ceremonies. They also built a network of roads and forts along the Salt Road to protect their trade routes.

The Salt Road passed through a few important cities, including:

Sijilmasa (Morocco)

Taghaza (Mali)

Timbuktu (Mali)

Oualata (Mauritania)

Awdaghost (Mauritania)

These cities were trading centres for a wide variety of goods, including salt, gold, slaves, textiles, and spices. The Salt Road also played an important role in the exchange of ideas and cultures between the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean region.

The Salt Road during the Middle Ages

The Salt Road continued to be important throughout the Middle Ages. The Arabs played a major role in the Salt Road during this period. They controlled trade routes between the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea, and they traded salt with the peoples of North Africa and Europe.

Late Decline of the Salt Road

The Salt Road declined in the 16th century AD, with the discovery of new trade routes to Africa by the Europeans. However, the trade in salt continued throughout the modern period, and the Salt Road remained an important trade route until the early 20th century.

The Royal Road

The Royal Road

Long before the Roman legions marched on their meticulously engineered roads, an even older, equally vital network crisscrossed the ancient Near East: the Royal Road. More than just a simple route, this vast infrastructural achievement served as the nervous system of the mighty Achaemenid Persian Empire, an empire stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River.

How the Royal Road Worked

Mounted couriers from the Chapar Khaneh, or Courier House, their horses galloping across vast distances, could deliver an urgent dispatch from the city of Susa, the Persian capital, all the way to Sardis in Lydia, near the Aegean coast, in just nine days, a journey that would take ninety days on foot.

This incredible feat, covering some 2,700 kilometres, wasn't achieved through magic, but through meticulous planning and a system of waystations. As the Greek historian Herodotus marvelled, "There is nothing in the world which travels faster than these Persian couriers." He went on to describe the system: "It is said that as many days as there are in the whole journey, so many are the men and horses that stand along the road, each horse and man at a day's journey apart; and these are stayed neither by snow nor rain nor heat nor night from accomplishing their appointed stage with utmost speed."

The couriers worked one day on, one day off. They rode for one day then transferred their messages to a fresh horse ridden by a courier who had been resting since the previous day.

Formalizing Ancient Routes

Darius the Great, who ruled the Persian Empire from 522 to 486 BC, is largely credited with formalizing and extending the Royal Road. While earlier versions of the route certainly existed, Darius recognized its strategic importance for governing such a vast realm. He understood that effective communication was paramount to maintaining control, collecting taxes, and mobilizing troops swiftly if rebellion stirred in distant satrapies.

The route taken by the Royal Road is not the shortest route. In its western parts, the Royal Road lies on the foundations of a path created millennia previously by Assyrian merchants who ran donkey caravans from Anatolia, to Mesopotamia and beyond to bring tin from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan.

The Silk Road’s Older Sibling

The Royal Road wasn't merely for imperial dispatches. Merchants, too, benefited immensely. Goods flowed across the empire, facilitating a robust economy. From the luxurious, colourful textiles of Babylon to the precious metals of Anatolia, the Royal Road became a conduit for wealth and cultural exchange. Travellers would have encountered a cornucopia of peoples, languages, and customs along its length, reflecting the diverse nature of the Persian Empire itself. The Royal Road was the Silk Road's lesser-known but equally significant older sibling.

Tracing the Route of the Royal Road

While much of the Royal Road's physical structure has vanished with time, archaeological discoveries occasionally offer glimpses into its past glory. Sections of paved road, remnants of watchtowers, and the foundations of waystations have been unearthed, providing tangible evidence of this ancient highway. These stations, typically spaced a day's journey apart, provided fresh horses, provisions, and lodging for couriers and travellers, ensuring a remarkably efficient and relatively safe passage.

The road facilitated an unprecedented level of connectivity for its time, playing a crucial role in shaping the political, economic, and cultural landscape of the ancient world.

The Spice Road

The Spice Road

The Spice Road was a network of trade routes that connected Europe, Asia, and Africa. It eventually became one of the longest trade routes in the world, stretching over 6,000 kilometres. It was used to trade a wide variety of goods, including tin, spices, silk, textiles, and porcelain. The Spice Road was one of the most important trade routes in the world for centuries.

The Spice Road had two elements: the maritime routes and the overland trails.

Sumerians Establish the Spice Road down the Persian Gulf

About 3000 BC, the Sumerians established a trading post about halfway down the Persian Gulf at a place called Dilmun. It's purpose was to facilitate the movement of copper from what is now Oman, to the city of Ur on the Euphrates river. By 2050 BC, Dilmun was acting as a conduit for cargoes from as far afield as the Indus valley civilisation in Pakistan.

Egyptian Expand the Spice Road via the Red Sea

As early as 2500 BC, Egyptian ships sailed down the Red Sea, over 1500 kilometres, to the land of Punt, modern Yemen and Somalia. From a wall painting in her mortuary sanctuary, we know that Queen Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt from 1479 to 1458 BC, ordered an expedition to Punt. Galleys, about eighty feet long and equipped with sails and oarsmen, were loaded with grain and bails of textiles for the outward journey and returned with, 'marvels of the country of Punt: all goodly fragrant woods of God's land, heaps of myrrh resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony, and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, khesyt wood, with ihmut incense, sonter incense, eye-cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of southern panther, with natives and their children. Never was brought the like of this for any king who had been since the beginning.'

Ramesses II (1279 to 1213 BC), loved Indian black pepper. He had some of his favourite spice entombed with him to sustain him on his journey to the afterlife.

Phoenicians on the Spice Road

Somewhat later the same voyages were being performed by the Phoenicians. King Solomon (970 to 931 BC) is reputed to have built a navy on the shores of the Red Sea in the land of Edom (the Gulf of Aqaba, the northeastern tip of the Red Sea). Hiram, king of Tyre from about 980 to 947 BC, crewed the ships with his men and sailed to Ophir (probably India) where they loaded the ships with four hundred and twenty talents of gold (about thirteen tons), peacocks, ivory and apes, that they took to King Solomon.

In 2025 AD, according to a paper published in the journal Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, researchers analysing the contents of 27 flasks from five archaeological sites in Palestine that date back around 3,000 years, have found that 10 of the flasks contain cinnamaldehyde, the compound that gives cinnamon its flavour, indicating that the spice was stored in these flasks. At this time cinnamon was found in the Far East with the closest places to Palestine being southern India and Sri Lanka located at nearly 5,000 kilometres away. The flasks themselves were made locally in northern Palestine. They are specially designed with a narrow opening and thick walls to carry precious contents.

Although the Phoenicians were primarily involved in maritime trading in the Mediterranean Sea, it is clear they obtained exotic products from the Far East via the established Spice Road.

The Canal of Darius the Great

The first person to directly link the Mediterranean to the Red Sea was Darius the Great, the Persian ruler of the Achaemenid Empire from 522 BC until 486 BC. He opened his canal between Zaqazaq on the Nile to modern Suez in 497 BC. The waterway fell into disuse during Alexander's conquest of Greece, Egypt and western Asia in the late fourth century BC. After Alexander died in 323 BC, his empire fragmented and Egypt found itself under the rule of Ptolemy, previously a general in Alexander's army.

He re-opened the trade routes down the Red Sea in order to obtain elephants from central Africa, the 'tanks of the ancient world', for use against the rival Seleucid Greek Empire in Persia. Ptolomy tried, without success, to reopen the old canal. The Romans later tried to build a canal along the same route, from the eastern arm of the Nile delta, via Wadi Tumilat to the northern end of what is now known as the Great Bitter Lake, just north of the Gulf of Suez to which it was connected by a narrow channel. This channel was shallow and tenuous; a brisk east wind combined with a low tide could render it high and dry.

Is this where Moses crossed the Red Sea?

Readers will no doubt, accurately, relate this phenomenon to the story of Moses crossing the Red Sea. Moses and his followers managed to cross at low tide but the following Egyptians were caught by the incoming tide and washed away.

Ptolemaic Greeks reach India

After 200 BC, Ptolemaic Greek merchants reached India via the Red Sea. Eudoxus of Cyzicus followed the Red Sea coast to Bab el Mandeb then followed the Arabian coast to the Strait of Hormuz, then hugged the Iranian and Pakistani coast until he reached the Indian trading centres. On the way he encountered the monsoons, the southwest monsoon during summer and the northeast monsoon during winter. Another Greek mariner, Hippalus, harnessed the monsoon winds to sail directly from Bab el Mandeb to the Malibar coast in India in a matter of weeks rather than months around the coast.

Indian Emissaries to Rome

During the Roman period, Indian ambassadors appeared in Rome bearing gifts such as Chinese silk, Indian ivory, monkeys, tigers, rhinoceros, and tigers. The most fashion conscious obtained a Latin speaking parrot. The most expensive item brought back from India was pepper that soon found its way into savoury and sweet dishes, medicines and wines. In return, India imported red Mediterranean coral, Roman glass (the finest in the world), lead from Spain, copper from Cyprus, tin from England, plus, of course, fine wines.

Expansion of the Spice Road on Land

The land based route started to extend its tentacles east from Mesopotamia somewhat later than the maritime routes, about 1975 BC, when Assyrian merchants, based in the karums of Anatolia, brought tin from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan to the Middle East.

The overland Spice Road really took off when the Phoenicians began trading spices from the Arabian Peninsula with other Mediterranean civilizations at the start of the first millennium BC.

The Spice Road during the Roman Period

The Spice Road flourished during the Roman Empire, as the Romans loved spice in their food. The Romans traded for spices with India, China, and Southeast Asia. They also established trading colonies along the Spice Road, such as Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Turkey.

The Spice Road during the Middle Ages

The Spice Road continued to be important throughout the Middle Ages. The Arabs played a major role in the Spice Road during this period. They controlled trade routes between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, and they traded spices with India, China, and Southeast Asia.

Decline of the Spice Road

The European Age of Exploration led to a decline in the importance of the Spice Road in the 16th century. The Europeans discovered new trade routes to Asia and Africa, and they began to trade directly with these regions.

Despite the decline of its importance, the Spice Road continued to be used until the 19th century. It was finally abandoned when the Suez Canal was opened in 1869. The Suez Canal provided a faster and more efficient way to transport goods between Europe and Asia.

The Spice Road had a major impact on the world. It facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas between different civilizations, and it helped to spread new technologies and cultural practices throughout the world. The Spice Road also played a major role in the development of the global economy.

The Trans-Saharan Trade Route

The Trans Sahara Routes

The Trans-Saharan Trade Route was a network of trade routes that connected North Africa with West Africa. It was used to trade gold, slaves, and other goods. It developed in parallel with the Salt Route and many of the tracks between oasis followed by the caravans were identical.

The Trans-Saharan Trade Route began to develop around 3000 BC, when the ancient Egyptians began trading for gold from West Africa. Gold was a highly prized commodity in the ancient world. It was used to make jewellery, coins, and other luxury goods.

This route flourished during the Islamic era, as the Muslims also prized gold and other goods from West Africa. The Muslims also built a network of roads and caravanserais along the Trans-Saharan Trade Route to protect their trade routes. The Trans-Saharan Trade Route declined in the 16th century AD, with the discovery of new trade routes to Africa by the Europeans. However, the trade in gold and other goods continued throughout the modern period, and the Trans-Saharan Trade Route remained an important trade route until the early 20th century.

The Silk Road

The Silk Road

The Silk Road was a later comer to the vast trading network that by now spanned the entire known world. Many of the individual routes were the same as used by the Spice Routes.

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes that connected the East and West for over 1,500 years. The Silk Road derives its name from the highly lucrative trade of silk textiles that were produced almost exclusively in China.

From China to the Mediterranean

The network began with the Han dynasty's expansion into Central Asia around 114 BC and stretched to the Mediterranean Sea, passing through Central Asia, the Middle East, southern Europe, and East Africa. Silk became a highly prized commodity in the west, and it was used to make clothing, tapestries, and other luxury goods.

The Silk Road was not a single road, but rather a network of routes that changed over time.

Transfer of Technology down the Silk Road

The Silk Road was used to trade a wide variety of goods, including silk, spices, textiles, porcelain, and precious metals. Like the Spice Road, it also played an important role in the exchange of ideas and cultures between the East and West, particularly from China from which country the West learnt how to make paper, print, manufacture silk, make gunpowder and use the compass.

The Silk Road flourished during the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD), when China was a major economic and cultural power.

Decline of the Silk Road

The Silk Road declined in the 15th century AD, due to several factors, including the rise of the Ottoman Empire and the discovery of new trade routes to Asia by the Europeans.

Despite its decline, the Silk Road had a major impact on the world. It facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas between the Far East and Europe, and it helped to spread new technologies and cultural practices throughout the world. The Silk Road also played a major role in the development of the global economy.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution