Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The Ancient Tin Roads

This is the story of the ancient tin roads that used a combination of even more ancient land routes to feed into the Mediterranean maritime trading networks to meet the demands for bronze in the emerging civilisations in the Middle East.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-23 | Last Updated 2025-07-13 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 14,707 times

Tin ingots from Israel from Cornwall - 12th c BC

Why was the Tin Route important?

Tin is used with copper to make tin-bronzes. Early bronzes were produced almost by accident by smelting copper ores that contained arsenic, so called arsenic-bronzes. Occasionally a small amount of tin will be found associated with copper in ores such as stannite. Early in the bronze age, the health hazards of using ores containing arsenic were realised and the search for tin ore, cassiterite, began.

The demand for tin within the bronze age civilisations in the Middle East soon outsripped that supplied from the known deposits in Anatolia making the roads to other sources of supply of strategic importance.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Sources of Cassiterite (Tin) in Western Europe

Ancient sources of cassiterite

Cassiterite is not common. In western Europe it occurs in large quantities in Cornwall and Devon in Britain, Brittany in France, Galicia in Spain, and northern Portugal. Smaller deposits of cassiterite were also found in Monte Valerio in Tuscany, Sardinia, the Massif Central in France, Serbia, and Turkiye.

The tin mine at Kestel, in Southern Turkiye, is the site of an ancient cassiterite mine that was used from 3250 to 1800 BC. It contains miles of tunnels, some only large enough for a child.

Tin is also found in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan, that show signs of having been exploited starting around 2000 BC.

First Uses of Tin Bronze in ancient times

Image credit: Dating the transition to full tin-bronze use in Europe and the Mediterranean (adapted from Pare 2000 with additions). R. Alan Williams et al.

The first use of tin-bronze is recorded in Serbia where several bronze objects have been found dated between 4650 BC to 4000 BC. Those bronzes probably used locally sourced deposits of cassiterite.

By 3200 BC, tin was being exported to Cyprus where it was alloyed with native copper and the resulting bronze was exported to various countries in the eastern Mediterranean. This tin probably came from Turkiye.

In the Iberian Peninsula, the first recorded use of tin bronze is between 2300 and 1300 BC at Bauma del Serrat del Pont in Girona region of northeastern Spain. The tin probably came from Brittany.

The Tin Trade

By 2000 BC, the extraction of tin in Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal was well underway and tin was traded to the Mediterranean sporadically from all these sources.

Evidence of a direct tin trade between Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean has been demonstrated through the analysis of tin ingots dated to the 13th-12th centuries BC from sites in Israel, Turkiye, and modern-day Greece; tin ingots from Israel, for example, have been found to share chemical composition with tin from Cornwall and Devon.

A shipwreck occurred at Hishuley Carmel, Israel, in the 13th-12th century BC. On board were tin ingots from Cornwall and Devon. This was confirmed by a study published in the journal Nature Communications in 2022, which used a combined approach of tin and lead isotopes together with trace elements to narrow down the potential sources of the tin.

The study found that the tin ingots from Hishuley Carmel were most likely sourced from the tin mines of Cornwall and Devon. This is significant because it provides direct evidence for maritime trade between the British Isles and the Levant during the Late Bronze Age.

Both tin and copper were being transported by sea in the eastern Mediterranean as evidenced by the Uluburun wreck off the coast of Turkiye, dated to about 1300 BC that was carrying 300 copper ingots weighing 10 tons and 40 tin ingots weighing 1 ton.

Somewhat later, the 7th or 6th century BC Rochelongue depositional site off the southern coast of France included quantities of lead that proved to originate in Cornwall and Devon.

The question is, "!What routes were used to transport the tin from the major cassiterite deposits to the Mediterranean Basin?"

The Tin Routes

European rivers created a route nexus

The first tin routes occurred long before the maritime trading powers from the eastern Mediterranean with sail driven boats reached western Europe. It is likely that, apart from short sea crossings by local sewn planked or stretched hide boats powered by oars or paddles, the greater part of the journey would have been overland.

At this stage it is worth noting that the headwaters of the rivers Saone, Loire, Seine, Moselle, Rhine, and Danube converge within a radius of 200 kilometres from a broad arc of land north of the Alps that extends from Burgundy to Bohemia. It is in effect a communications hub that connects Europe, north to south and west to east, and has been since the early Neolithic period. The area was a nexus for multiple trade routes. A traveller from Marseilles would pass this way to reach the North Sea or, deviating via the Danube and Moravia, the Baltic. The Loire to the Mediterranean via the Rhone was a well-trod path. Another itinerant may pass through on his way from the Atlantic to the Black Sea. Yet another from the eastern Mediterranean could access this hub via the Adriatic, the Po valley, and the Alpine passes.

Tin from Brittany or Cornwall had diverse ways of reaching the Mediterranean. The only part of Europe divorced from this network is the Iberian Peninsula, cut off from the rest of Europe by the Pyrenees. Iberia, has often gone its own way.

Tin from Brittany to the Mediterranean

It is likely that from very early on, before 2300 BC, tin from Brittany was taken down the ancient trade routes that followed the river Loire valley to its headwaters and then across into the Rhone valley to emerge in the Gulf of Lion. An alternative route, equally as ancient, is up the river Gironde, across to the River Aude at the Carcassonne Gap and thence into the Gulf of Lion in the vicinity of Narbonne.

The very early tin bronze at Gerona in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula probably used tin that had traversed the latter route. The tin was then taken a hundred or so kilometres south, down the coast.

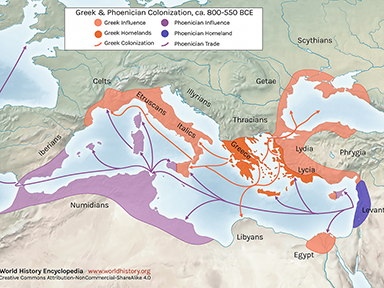

Until about 600 BC, the tin arriving on the Mediterranean coast in the Gulf of Lion must have been taken in small offshore craft and filtered through to Italy and Sardinia where it would have entered the Minoan and Mycenaean trade networks. After the 6th century BC, the tin arriving in the Gulf of Lion would have gone straight into the Greek emporium of Massalia and then onto Greek or Phoenician boats bound for the east.

Tin from the Middle East to the Mediterranean

Until 2022, historians doubted that the tin from ancient mines in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan made its way to the Mediterranean. However, analysis of the tin ingots from the Uluburun showed that about one third of the tin cargo originated in Uzbekistan whilst the other two thirds was from Turkiye. It transpires that small-scale communities or free laborers, who lay outside the purview of kings, emperors, or any other political force had managed to forge access to a vast international trade network via the Spice Road. At the time, the passes between Iran and Mesopotamia did not have any central authority, major industrial centre, or empire to tax or otherwise hinder trade. The tin made the arduous 3,200-kilometre journey through valleys and mountains in a desert landscape to Haifa where the Uluburun cargo was probably loaded.

This trade in tin was coordinated by Assyrian merchants, based at Kultepe-Kanesh in central Anatolia.

Kultepe-Kanesh Karum

The archaeological site of Kultepe-Kanesh in Anatolia (present-day Turkiye) offers a unique perspective on long-distance trade networks during the Bronze Age (1975-1750 BC). This significance stems from the presence of a large Assyrian merchant enclave, known as a "karum." These resident Assyrian families, originating from Assur some 775 kilometers away, meticulously documented their commercial activities on clay tablets. This extensive archive, exceeding 23,500 tablets, provides unparalleled insights into the organization and scale of trade routes, particularly concerning the previously obscure tin trade.

Kultepe-Kanesh functioned as a pivotal commercial hub, facilitating exchange between Anatolia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. The Assyrian merchants of the karum orchestrated a complex logistics network, utilizing large donkey caravans for transporting goods. These caravans, documented as comprising 200-250 donkeys, each capable of carrying 60 kilograms of cargo, traversed between 30 and 50 kilometres per day, for 35-40 days. The tablets reveal the trade in precious metals like gold and silver from Anatolia, textiles from Mesopotamia, and the commodity we are interested in here, tin.

The record of tin shipments in the Kultepe-Kanesh archives sheds new light on the extent of Early Bronze Age trade networks. Given the likely origin of this tin from present-day Uzbekistan, it becomes evident that Anatolian tin resources were insufficient to meet the growing demand for this essential metal as early as 1920 BC. This finding underscores the interconnectedness of early societies and the vast distances traversed to secure vital resources.

Tin from Cornwall to the Mediterranean

At some time before 1300 BC, the amounts of tin leaving Brittany were no longer sufficient to fulfil the needs of the emerging powers in the Middle East. Tin from Cornwall and Devon started to appear in the Mediterranean basin.

The Voyage of Pytheas

Sometime around 320 BC, a Greek merchant from Massalia called Pytheas, made an exploratory journey to Britain. He recorded his fascinating journey in a book called On the Ocean (Peri tou Okeanou). He saw British inhabitants at a place called Belerion, mining tin bound for Gaul. Many later historians such as Pliny quoted Pytheas in their own narratives. Pliny writes: "there is an island called Mictis lying six days sail inwards from Britannia where tin is to be found. The Britons cross to the island in wicker boats sewn over with hides".

The Writings of Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus (writing between 60 and 30 BC) tells us of a promontory called Ictis, identified as either St. Michael's Mount, in Mount's Bay, off the south coast of Cornwall, or Mount Batton in Plymouth Sound, where the local inhabitants traded tin ingots with foreign merchants. A peninsula such as either of the above was often chosen as neutral trading ground by ancient marine traders and there is no reason to think that either or both had not been used as such for millennia.

Three wreck sites off the south coast of England may give a clue as to the route taken by the tin after it was loaded into hide boats at St. Michaels Mount or Mount Batton.

The Salcombe Bay Wrecks

The first site, in Salcombe Bay, has two Bronze Age wrecks, both dated to 800 - 700 BC and called Salcombe A and Salcombe B.

Salcombe A cargo included Bronze Age swords and rapiers dating to between 1300 and 1150 BC, rapier blade fragments and palstaves (bronze axes) dated to the same period and a carp's tongue sword dated to between 800 and 700 BC.

Salcombe B carried a massive load of copper and tin ingots. The copper was analysed and came from a metalworking site in Switzerland. The cargo also included an object made in Sicily, called Strumento con Immanicatura a Cannone (having a cannon-shaped handle), which, as yet, has no known purpose. The Strumento is dated to between 1200 and 1100 BC and is currently displayed in the British Museum.

The Langdon Cliff, Dover wreck

The second wreck site is at the foot of Langdon cliff just east of Dover and consists of a collection of artefacts, including tools, weapons, and ornaments made in France. These items have been dated to 1100 B.C. Over 350 artefacts have been recovered to date. Again, the bronze originated in northern France but on this wreck some of the pieces had been cut up to facilitate packing.

The conclusion is that the bronze on all three vessels was scrap metal being brought back to Britain to be reworked. In other words, both wrecks are positioned on the return route taken by traders crossing the English Channel.

The Bigbury Bay wreck

The third wreck site is in Bigbury Bay in south Devon, 5 kilometres northwest of Salcombe. Its cargo was tin ingots in the shape of knuckle bones and probably represented tin being taken from Cornwall to the continent. This vessel was apparently on the outward journey although when it foundered is not known, it could be during the Bronze Age or later.

From the English Channel to the Mediterranean

Once cargoes arrived on the continent, several well-trodden paths end on the shores of the Mediterranean. The problem is reaching the continent in a time before ships carried sails. I still have problems reconciling the use of small non sailing boats, probably made of stretched hide or sewn planks, crossing the Western Approaches directly from Cornwall to the north coast of Brittany heavily laden with metal ingots.

That there was communication between Brittany and the south of England since the 4th millennium BC is indisputable but cargoes, if any, would have been light. With a heavy load, it seems to me more reasonable to coast hop east, as far as Dover, from where the coast of France is easily visible. A coast hopping journey southwest from Calais takes you to the River Seine, a similar coast hopping journey northeast takes you to the mouth of the river Rhine. Until sailing technology arrived in southern Britain, which may have been as late as 600 BC, my view is that such coast hopping is the most likely means by which Britain imported and exported bulk goods from and to the continent.

The Seine, Rhone route was well known in antiquity and would explain the tin found in the Rochelongue deposit in southern France. The tin would then enter the Sardinia, Sicily network and from there to the eastern Mediterranean.

From the Rhine delta, the river Rhine to the river Danube route to the Black Sea was a known ancient trail.

From the Black Sea, local craft would have taken the tin to Turkiye.

The Findings from Must Farm, Cambridgeshire

The Bronze Age connections between Britain, Europe and the Middle East are reinforced by finds at Must Farm, near Peterborough in Cambridgeshire. Must Farm was the location of a fenland Bronze Age village that was built between 1000 and 800 BC. Only occupied for about six months, the village burnt down, preserving some remarkable artefacts including glass beads from Egypt and Iran, a bead made from raw tin, and a bead made from Baltic amber. At the time, present day Iran was part of the Assyrian Empire. Clearly, the 'tin road' was used for far more than just the metal.

Surprising Link to the Nebra Sky Disc

The discovery of the Nebra Sky Disc in 1999 AD and x-ray fluorescence analysis of the gold and bronze of which it is made, revealed another link in the Tin Road story. The disc was found buried on the Mittelberg hill near Nebra in Germany. Nebra is in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt, almost in the centre of the country. It is dated by archaeologists to between 1800 and 1600 BC and attributed to the Early Bronze Age Unetice culture. Some of the gold from the disc originated in the Carnon valley in Cornwall and some of the tin in the bronze also came from Cornwall.

The discovery has three notable implications for the account of how the tin roads developed. The location of Nebra emphasises the overland route taken by metals from Cornwall. The date of the Nebra disc pushes the date at which metallic ores were traversing the intercontinental tin route by at least 300 years. The discovery of Cornish gold indicates that tin was not the only metal making this journey.

Carrying Bulk Cargo Bronze Age Style

An interesting discovery of five canoes in a lake village called La Marmotta, near Rome in 1989 AD may help explain how bulk cargoes were carried, or rather towed.

The five canoes are the oldest boats ever found in the Mediterranean, and among the ten oldest known in Europe. Radiocarbon dating placed their origins between 5700 and 5100 BC. One of the most exciting finds has been wooden T-shaped objects, drilled with two to four holes, that explain how the canoes were outfitted to carry large loads. The structure suggests the boats were towed using rope, allowing for the movement of goods, people and animals.

Latest Research Confirms Cornwall – Eastern Mediterranean link and the overland tin routes

A recent paper, published in May 2025, reinforced previous research linking Cornish tin with the shipwrecks off Hishuley Carmel and the controversial deposits found at Rochelongue off the southern coast of France dated to the 7th – 6th centuries BC.

Bronze Age–Early Iron Age tin ingots recovered from shipwrecks off the coast of Israel have been provenanced to tin ores in south-west Britain. This is a central finding linking the two regions.

This provenance was determined using a novel combination of three independent analyses: trace element analysis, lead isotopes, and tin isotopes applied to tin ores and artefacts. The research successfully developed methods to analyse the composition of tin ores (cassiterite) and tin metal artefacts.

Tin artefacts from Cornwall and Devon show high indium levels, and all Bronze Age to Early Iron Age tin ingots from Mediterranean shipwrecks analysed to date have indium levels consistent with Cornwall and Devon ores, or to a lesser extent, Erzgebirge ores, but not Iberian or French sources.

The lead isotope analysis, used to determine the geological formation age of the ore source, showed that ingots from shipwrecks near Israel (Hishuley Carmel, Kfar Samir South & near Haifa) and Rochelongue (off southern France) had mean predicted formation ages (290 Myr and 278 Myr respectively) that are clearly consistent with the geological formation age range of the Cornwall and Devon granites (274–293 Myr), rather than the older Erzgebirge sources (318–323 Myr).

The trace element and isotope results from tin ingots found off the coast of Israel were found to be nearly identical to those of ingots found in south-west Britain (like those from Salcombe).

Cornwall and Devon ore and metal tin isotope data ranges are fully consistent with the Israel shipwreck and Rochelongue deposit tin ingots.

The results from the shipwrecks near Israel strongly suggest that the widespread adoption of full tin-bronze metallurgy, termed 'bronzization', in the Eastern Mediterranean during the period of c. 1500–1300 BC was primarily driven by European tin sources, particularly from south-west Britain, rather than Central Asian sources.

While the research proves the link through tin provenance, it notes that there is no evidence for a direct connection between Britain and the Eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium BC. The tin was likely moved along smaller riverine, overland, and maritime routes across continental Europe, constituting a 'down-the-line' trade network. The Cornwall-and-Devon tin found at the Rochelongue site (c. 600 BC) off southern France provides direct evidence of tin trade across France to the Mediterranean, potentially then connecting to regions like Sardinia, which traded with Sicily and Cyprus from c. 1500 BC, thus reinforcing the hypothesis put forward by this author and first published in October 2023.

The pan-European trade in tin around 1500–1300 BC was part of a wider network trading various goods. The presence of Cypro-Minoan inscriptions on the tin ingots provenanced to Cornwall and Devon found on shipwrecks near Israel, alongside lead ingots from Sardinia on the same shipwrecks, supports these complex trade connections.

In summary, the latest research provides robust analytical evidence, particularly from trace element and isotopic analysis of shipwreck ingots, demonstrating that tin originating from south-west Britain (Cornwall and Devon) reached the Eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, playing a significant role in the region's transition to full tin-bronze metallurgy.

Galician Tin Route

Galician tin has been mined and used, together with copper, to make bronze since before 1250 BC. Much of the bronze manufacturing took place locally, mainly in the Mondego, Vouga and southern Douro rivers with isolated smelting sites scattered through northern Portugal and into Spain. One site, Punta Muros in northwest Spain has been interpreted as a fortified bronze factory.

At another site, Castro de Nossa Senhora, Baioes in central Portugal, moulds together with manufactured pieces: socketed spearheads, bifacial double looped palstaves, unifacial single looped palstaves, daggers, rings, tranchet, chisels, etc. were found. Other nearby sites in the basins of the rivers Mondego, Vouga and southern Douro rivers have been excavated and have since been labelled the Baioes/Santa Luzia cultural group. Most artefacts found in this group are related to the 'Atlantic Bronze Age' traditions, but many artefacts are also clearly related to Mediterranean models for instance: bowls with omphalos bottom; articulated roasting spit fragments; old types of fibulae fragments and early iron daggers from 12-10th century BC contexts. Some of these finished products did make their way outside the Iberian Peninsula via ancient inland routes from settlement to settlement and local coast hopping traders. These sites were occupied between 1250 and 550 BC.

A little of the tin found its way south into southern Portugal and southern Spain where it was used by the southwestern Iberian bronze culture and the Argar civilisation until about 700 BC.

It was not until the arrival by sea of eastern traders that tin from Galicia made it out of the peninsula, except as an integral part of finished bronze products. The evidence suggests that, after the Phoenicians established trading posts along the Iberian Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts during the 9th century BC, tin from Galicia and northern Portugal was taken south to the most northerly Phoenician trading post which was establish a few kilometres upstream of the Mondego estuary at Castro de Santa Olaia or Santa Eulalia. Castro de Santa Olaia was established about 850 BC. From there it would have travelled to Huelva and Gades and on into the Mediterranean.

Summary

Image credit: Possible down-the-line trade routes from south-west Britain to the eastern Mediterranean through archaeologically defined areas of intensive interaction c. 1300 BC (adapted from Mordant et al. 2021; Knapp et al. 2022;) (figure by R. Alan Williams et al).

Excluding the use of local tin deposits, the tin route(s) developed after 3200 BC when tin, probably from Turkiye, was making its way by local traders on land and sea, to Cyprus.

Sometime before 2300 BC, tin from Brittany was making its way to the Gulf of Lion via the Gironde or Loire valleys. From there it infiltrated into the Minoan/Mycenaean maritime trading networks.

Between 1920 and 1850 BC, tin from Uzbekistan was being taken by land down the Spice Road to the Middle East and Turkiye where it would enter the Mycenaean sea trading network.

Between 1800 and 1600 BC, Cornish tin (and gold) was making its way at least as far as central Germany.

About 1300 BC, tin from Cornwall and Devon started to arrive at the Black Sea, probably via the rivers Rhine and Danube, and thence to Turkiye where it would enter the Mycenaean trading network.

By 600 BC, and probably much earlier, Cornish tin was travelling down the Seine and Rhone to arrive in southern France, where it filtered into the Sardinia, Sicily and eastern Mediterranean, probably Greek, networks bearing in mind the synchronicity of the founding of Marsailles (about 600 BC) and the dating of the Rochelongue deposits.

Finally, the Galician tin arrived in the Mediterranean maritime trading network shortly after 850 BC having travelled just a short distance overland from Galicia and northern Portugal to Castro de Santa Olaia. That tin entered the Phoenician and Greek maritime trading networks.

References

Arif, R. Four Late Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean and Aegean, and Their Connections to Cyprus (2016).

Artzy, M. 2006 'The Carmel Coast during the Second Part of the Late Bronze Age: A Center for Eastern Mediterranean Transshipping.' Bulletin for the American Schools of Oriental Research 343: 45-64.

Broodbank, C. 2013 The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World. London: Thames & Hudson.

Galili, E. 'A Late Bronze Age Shipwreck with a Metal Cargo from Hishuley Carmel, Israel.' International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 42 (1): 2-23.

Liverani, M. Prestige and Interest, International Relations in the Near East, 1600-1100 B.C., Padua, 1990;

Muhly, James D. "The Sources of Tin in the Bronze Age." In The Bronze Age of the Mediterranean, edited by N. K. Sandars, 202-223. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Wacshmann, S. 2008 Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Williams, R. A., Montesanto, M., Badreshany, K., Berger, D., Jones, A. M., Aragón, E., … Roberts, B. W. (2025). From Land’s End to the Levant: did Britain’s tin sources transform the Bronze Age in Europe and the Mediterranean? Antiquity, 1–19. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.41

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

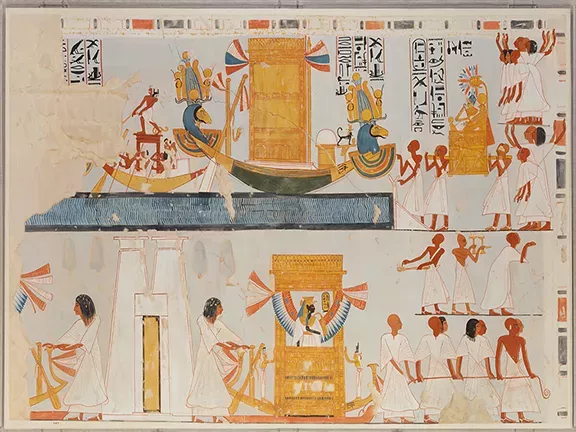

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

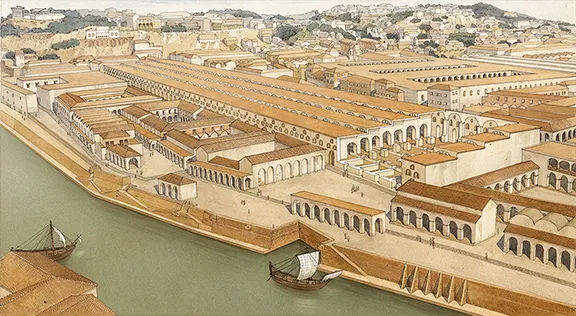

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution