Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 8th c BC - 8th c AD

Before the foundation of Alexandria in 331 BC, Thonis-Heracleion was the obligatory port of entry to Egypt for all ships coming from the Greek world. The city was probably founded around the 8th century BC, underwent diverse natural catastrophes, and finally sunk entirely in the 8th century AD.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-16 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 5,584 times

Statue of Amun-Ra - Franck Goddio

When was Thonis-Heracleion founded?

The city was originally built on several islands in the Nile Delta, possibly as early as the 12th century BC although its foundation as a Greek emporium probably dates to the 8th century BC, one of, if not the first overseas colonies established by the Greeks as they emerged from the 'Greek Dark Ages' which followed the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Where was Thonis-Heracleion located?

Location of Thonis-Heracleion - copyright Mail on Line

Thonis-Heracleion was an ancient Egyptian port city located near the Canopic Mouth of the Nile, about 32 kilometres northeast of Alexandria on the Mediterranean Sea and 72 kilometres north of Thonis- Abu Qir Bay, currently 7 kilometres off the coast, under ca. 5.8 metres of water, near Abukir.

Discovering Thonis-Heracleion

Ptolemaic Queen - Franck Goddio

The ruins of Thonis-Heracleion were rediscovered in the 1990s by a team of archaeologists led by Franck Goddio. Modern archaeological methods, mapping techniques and accurate recording of finds has allowed researchers to put together a detailed geography and history of the city.

Why was Thonis-Heracleion founded?

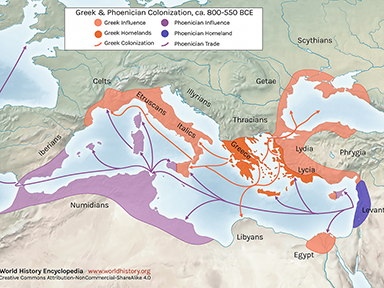

The Greeks were determined to create an overseas trading empire and Egypt had long been a trading partner with the Phoenicians. However, trade with the Phoenicians was disrupted in the mid-eighth century BC when an independent native dynasty began to rule Nubia, or Kush, from Napata in what is now the Sudan, and extended its influence into southern Egypt.

In about 730 B.C., the Egyptian rulers Namlot and Tefnakht joined forces to extend their control farther into Upper Egypt. The Nubian king, Piankhy Piye perceived this as a threat to his independence and moved against the Egyptian coalition. His invasion proved successful, and the various Egyptian rulers known from the later eighth century submitted to his leadership at Memphis about a year later.

It seems likely that the Greeks stepped in about this time to trade with the new Nubian leadership. Egypt was not the only target for the Greeks during the 8th century BC. They also established colonies on the south and west coasts of Italy (Magna Graecia) and around the Black Sea.

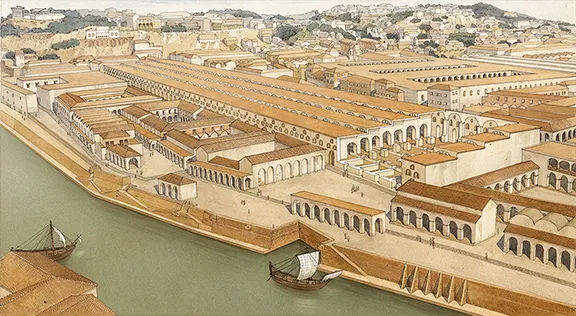

What did Thonis-Heracleion look like?

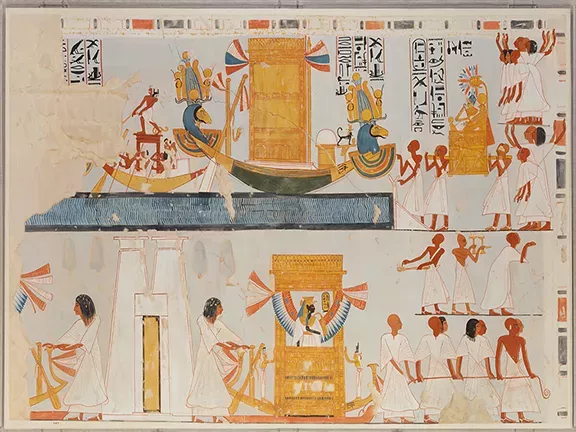

Thonis-Heracleion was built around a central temple dedicated to Khonsu, son of Amun, who was known among the Greeks as Herakles and was intersected by canals with several harbours and anchorages. Its wharves, temples, and tower-houses were linked by ferries, bridges, and pontoons. The city extended all around the temple and a network of canals in and around the city must have given it a lake dwelling appearance. On the islands and islets there were dwellings and sanctuaries. On the north side of the Temple to Herakles, a grand canal flowed through the city from east to west and connected the port basins with a lake to the west.

The city developed into a Greek emporium and by the Late Period (commencing 713 BC) it was the country's main port for international trade and collection of taxes and the main port of entry to Egypt for all ships coming from the Greek world. Thonis-Heracleion was also an important religious centre. It was home to the temple of Amun-Ra, one of the most important gods in the Egyptian pantheon and had a sanctuary dedicated to the Greek goddess Aphrodite. The existence of the Aphrodite sanctuary temple suggests that Greeks were allowed to relocate, live, and worship in the ancient city.

Who did Thonis-Heracleion trade with?

Gold jewellery and alabaster jar

Thonis-Heracleion initially traded with other Greek city states or polis such as the four Ionian cities of Chios, Klazomenai, Teos and Phocaea, the four Dorian cities of Rhodes, Halicarnassus, Knidos and Phaselis and the Aeolian city of Mytilene. By 550 BC trading ships were leaving Thonis-Heracleion bound for all the Greek colonies in the Black Sea, Italy, Sicily and as far west as Empuries on the Iberian Peninsula.

What was traded in Thonis-Heracleion?

The Greek traders brought silver, timber, olive oil and wine into Thonis-Heracleion where it was exchanged for faience vases, statues and ornaments, grain, fine Egyptian cotton, and papyrus.

What has been found at Thonis-Heracleion?

Inscribed Stelae - Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation, photo: Christoph Gerigk

Among the many treasures that have been unearthed from the sunken city since its discovery were the remains of a huge temple to the god Amun-Gereb. Statues of over five metres in height including a colossal statue of red granite (5.4 metres), representing the god Hapy, God of the Nile flood and symbol of abundance and fertility, a red granite colossal statue of a Ptolemaic king and another slightly smaller statue of a Ptolemaic queen have been recovered from the site.

The archaeologists also discovered artifacts from the temple's treasury, including gold jewellery and a "Djed pillar," a symbol of stability, made of a blue semi-precious stone called lapis lazuli. They also found silver platers and an alabaster container that were probably used to contain perfumes and unguents during ritual ceremonies.

In the anchorage and alongside the quays were 700 anchors and 79 ships dating from the 6th to the 2nd centuries BC, including a very rare find, a Ptolemaic fast galley.

The galley was about 25 metres in length and built using long mortise and tenon joints. It was a ship designed to be both rowed and sailed and had a flat bottom and flat keel, a typical Egyptian feature that made the boat suitable for navigating the river Nile.

The available data on local boat-building techniques during the Late (664- 332 BC) and Ptolemaic Periods (332 to 30 BC) of Ancient Egypt received a considerable boost from the ancient Egyptian ships that were found on the site of Thonis-Heracleion in 2000. Many of these ships seem to belong to the baris-type as described in Herodotus in his Historia. The excavations of Ship 17 from Thonis-Heracleion helped to clarify several references from Herodotus' description that had previously been incomprehensible.

An inscribed stele found on the site indicates that late in its history the city was known by both its Egyptian (Thonis) and Greek (Heracleion) names, thus solving a problem that has beset researchers for many years since, until the discovery of the stele, Thonis and Heracleion were thought to be two separate cities. The intact stele, almost 2 metres high, is inscribed with the decree of Sais. It was commissioned by Nectanebos I (380-362 BC). The place where Pharaoh ordered it to be set up is clearly named: Thonis-Heracleion.

How did Thonis-Heracleion operate?

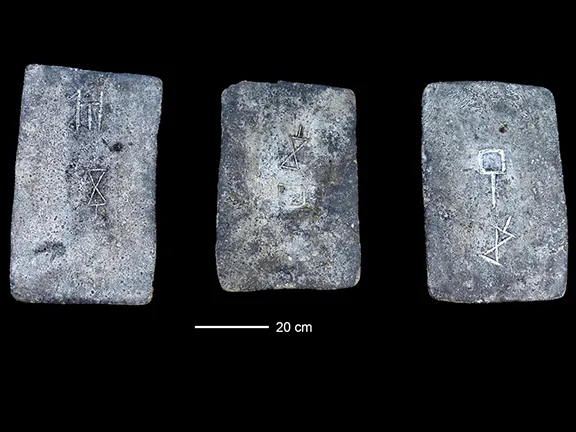

It is thought that Thonis-Heracleion was where seagoing ships unloaded their cargoes to have them assessed by temple officials who extracted taxes before transferring the cargo to Egyptian ships that went upriver. Excavations in the harbour basins yielded an interesting group of lead weights, likely to have been used by both temple officials and merchants in the payment of taxes and the purchasing of goods. Amongst these are an important group of Athenian weights. The port and its harbour basins also contain a collection of customs decrees and evidence of coin production.

What happened to Thonis-Heracleion?

Research has shown that Thonis-Heracleion was affected by geological and cataclysmic phenomena at different periods. It is now clear that a slow movement of subsidence of the soil affected this part of the south-eastern basin of the Mediterranean. The rise in sea level - already observed in antiquity - also contributed significantly to the submergence of the land. With the cooperation of the Smithsonian Institution of Washington and Stanford University, the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology made geological observations that brought these phenomena to light by discovering seismic effects in the underlying geology.

Geoarchaeological analysis of the sites also showed marks characteristic of the liquefaction of the soil in Aboukir Bay. These localized phenomena can be triggered by the action of great pressure on soil with a high clay and water content. The pressure from large buildings, combined with an overload of weight due to an unusually high flood or a tidal wave, can dramatically compress the soil and force the expulsion of water contained within the structure of the clay. The clay quickly loses volume, which creates sudden subsidence. An earthquake can also cause such a phenomenon (ancient texts mention the disappearance of cities here through both earth tremors and tidal waves). These factors, whether occurring together or independently, may have caused significant destruction and explain the submergence of Thonis-Heracleion in the 8th century AD.

References

2020, Belov, A., 2020, A note on the navigation area of the baris-type ships of Thonis-Heracleion, in E. Nantet (ed.) Sailing from Polis to Empire: Ships in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Hellenistic period, Nicosia.

Herodotus, 2003 (latest revision),Histories, translated by Aubrey de Salincourt, Penguin Books, London.

https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2013-03-15-maritime-trading-thrived-egypt-even-alexandria

https://www.franckgoddio.org/projects/sunken-civilizations/heracleion/#:~:text=Thonis%2DHeracleion%3A%20From%20Legend%20to%20Reality&text=The%20city%20was%20founded%20probably,in%20the%208th%20century%20AD.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heracleion

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution