Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

The Greek Emporium of Naukratis c 664 BC - c 700 AD

Until the discovery of Thonis-Heracleion in 2000 AD, Naukratis was considered the first Greek colony in Egypt. Naukratis was the site of an Egyptian town before the Greeks arrived, later becoming established as a military settlement occupied by mercenaries and then developed into an emporium.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-15 | Last Updated 2025-05-17 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 4,778 times

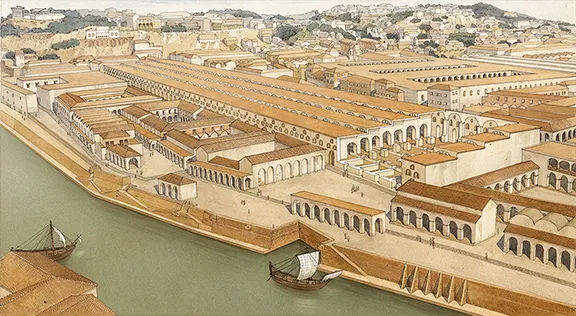

Artists impression of Naukratis

When was Naukratis founded?

The precise date of foundation is debated. Herodotus reports that Amasis (570 to 526 BC) gave Naukratis to Greek settlers, but there is evidence that it was already founded by then during the rule of Psamtek I (c 664 to 610 BC). The city had a 'Pan-Hellenic' character, meaning that it was not founded by one Greek tribe or state (normally Greek colonies were founded by only one city-state or polis).

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Where was Naukratis located?

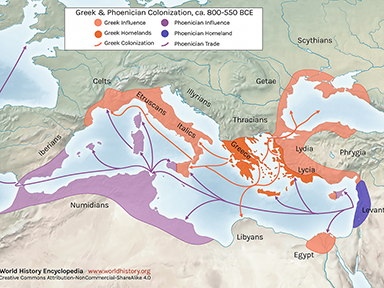

Map showing location of Naukratis

Naukratis was located on the Canopic branch of the Nile in the western Delta some 16 km from Sais and 72 kilometres south of Thonis-Heracleion. The Canopic tributary was one of the major waterways linking the Nile valley with the Mediterranean, and the most accessible of the Nile's tributaries during the Saite Period (664 to 525 BC). The early settlement then developed into a busy trading port. They exchanged goods with the Greeks and with other Mediterranean states. Greek traders settled in Naukratis, and a large Greek community began to develop.

Why was Naukratis founded?

From the time of its discovery in 1884 AD, until the discovery of Thonis-Heracleion in the year 2000, it was assumed that Naukratis's primary function was that of a trading colony that grew to become an emporium. However, the founding date for Thonis-Heracleion is reckoned to be sometime during the 8th century BC, which predates the earliest date for the founding of Naukratis, 664 BC.

Continuous underwater excavations at Thonis-Heracleion since 2000 have revealed a city of some magnificence and a large, thriving port that functioned as a hub of international trade.

It is difficult, given the prior existence of Thonis-Heracleion to rationalise a second colony devoted to trading, 72 kilometres south, i.e., further from the delta, and on the same tributary of the Nile. Naukratis is however only 16 kilometres from Sais, the capital city of Egypt at this time.

It is probable then that, as Herodotus reported, the initial function of Naukratis was a garrison town to supply Greek mercenaries for the Saite Pharaohs who ruled between 664 and 525 BC. It is recorded that Psamtik I used Greek mercenaries to help him unify Egypt. Greek mercenaries were also employed by Pharoah Apries (589 to 570 BC) to hold back the advance of Babylonians intent on conquering Egypt. The Greeks had superior hoplite armour and tactics and possessed invaluable naval expertise.

The Hellenion of Naukratis

The walled shrine or 'Hellenion' of the city (not yet identified on the ground) was installed by representatives of all three Greek tribes (Ionians, Dorians, Aeolians). Herodotus mentioned nine Greek city-states as sponsors: four Ionian cities; Chios, Klazomenai, Teos and Phocaea: four Dorian cities; Rhodes, Halicarnassus, Knidos and Phaselis; and one Aeolian city: Mytilene.

The Hellenion was a joint sanctuary for the nine founding polis. Dedications were made to specific gods, Apollo, the Dioscuri and Artenmis and to the 'Hellenic Gods'. The Hellenion appears to have been a sanctuary for all Greeks, no matter of their specific cult-affiliation or citizen-status with a particular polis. It was a place where Greeks could go and sacrifice generally to the gods of their pantheon.

Although only trading partners and not part of the founding group, Aegina, Samos, and Miletus all had their own temples (possibly pre-dating the Hellenion).

The Prostatai of Naukratis

Mentioned by Strabo, Herodotus and briefly by Diodorus, the prostatai (literally protectors) were the Greek governing body in Naukratis. It is likely that a member was chosen from each of the main active polis. They appear to have been both in charge of the general running of the town, as well as administrating and supervising the economic transactions of trade, and acting as the Naukratite officials dealing with the Egyptian officials who undoubtedly wanted to keep an eye on the activities in the port.

It is likely that the Hellenion was the administrative centre for the prostatai, a sort of city hall.

Who did the Naukratite trade with?

Herodotus tells us that Naukratis traded with: Ionians from Samos, Miletus, Chios, Teos, Phocaea, and Clazomenae; Dorians from Rhodes, Cnidus, Halicarnassus, and Phaselis; and Aeolians from Mytilene on Lesbos and the people of Aegina, the island close to Athens.

Archaeological records indicate that strong trading links existed between Naukratis and Italy, Cyrenaica, Phoenicia, Cyprus, and the Levant.

What was traded in Naukratis?

Faience Greek vase

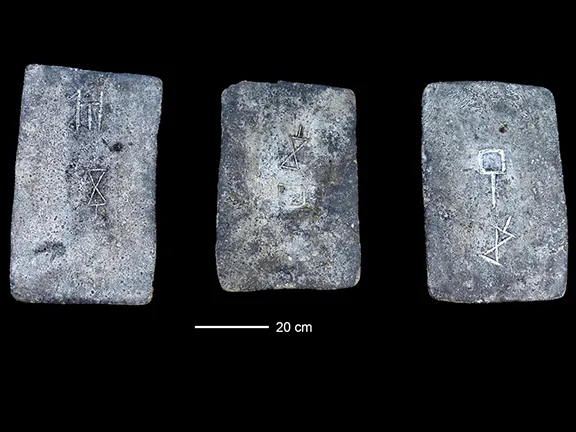

The Egyptians supplied the Greeks with grain, linen, and papyrus while the Greeks bartered silver, timber, olive oil and wine.

Naukratis also had various manufacturing areas, producing goods for export.

A faience factory that was found next to the temple of Aphrodite in the southern part of the town. What has struck many archaeologists is the close resemblance of the faience figures found here to those found on Rhodes (where faience objects were also manufactured). The island of Rhodes was one of the participants in the Hellenion, so had a strong link to Naukratis.

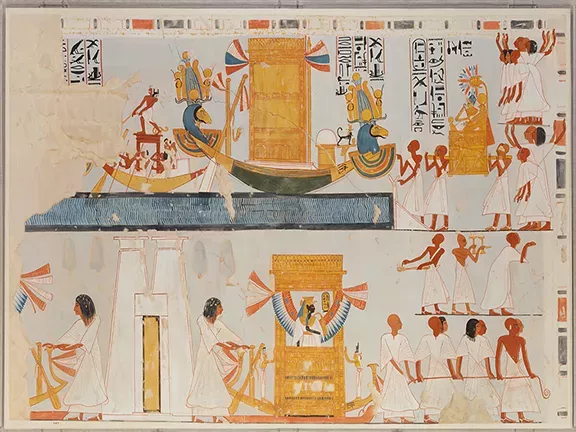

Ancient Egyptian faience is made of common materials, quartz, alkaline salts, lime, and mineral-based colourants. It may have been developed to simulate highly prized and rare semi-precious blue stones like turquoise. This man-made substance allowed the Egyptians to make a wide variety of objects covered in shiny, bright blue glaze, a colour that was closely linked with fertility, life, and the gleaming qualities of the sun. For Egyptians, the sculptures, vessels, jewellery, and ritual objects made of faience glimmered with the brilliance of eternity.

The word faience is a misnomer in this case. Egyptian faience should not be confused with the tin glazed pottery originating from Faenza and other towns in northern Italy in the late fifteenth century AD. The faience produced in Egypt has been found distributed across the western Greek world, especially on Samos and (not surprisingly) Rhodes.

Scarabs were also made in Naukratis (and on Rhodes). These small objects are found all over the Mediterranean basin from Spain in the west to the Levant in the east.

Ethnicity and Acculturation in Naukratis - Greek identity in Egypt

Scarab from Naukratis - British Museum

The temples set up by individual polis probably predate the Hellenion. This would suggest that the Greeks who first arrived at Naukratis thought of themselves as a Greek from their specific polis. As the settlement grew in both importance and wealth, the construction of the Hellenion would suggest that the Greeks in Naukratis began thinking of themselves as general Greeks with little ethnic difference between them.

If Naukratis was originally a garrison town for Greek mercenaries, then, faced with common enemies, a bond must have been forged between Greeks from different polis, somewhat like the French Foreign Legion. These Greeks lived in a country whose language and culture was very different from their own, and so probably felt that being Greeks together, and not divided by the identity of a polis, would make them stronger and safer.

Naukratites

The word 'Naukratite' meaning an object or person from Naukratis, did not appear until the 4th century BC about the time Naukratis became a polis when Alexander invaded Egypt in 322 BC.

Multiculturalism in Naukratis

Being a trading port and a joint project between several polis, Naukratis accommodated Greeks from at least 12 different polis spanning all three of the ' Greek tribes, Dorians, Ionians, and Aeolians. Nowhere in the ancient sources is there mention of any animosities between the citizens of the town. Life in Naukratis appears to have been a harmonic multicultural situation.

How the Greeks saw the Egyptians

Seated sphinx plate, Eastern Greek Orientalizing, 6th century BC, from Naukratis

Naukratis was a Greek settlement located in a developed, ancient civilisation. Even so, the Greeks were very much as 'Other' - like to the Egyptians as the Egyptians would have been to the Greeks.

The Greeks had mixed views on the Egyptians. On the one hand they were a foreign nation, 'barbarians' as were all the other peoples that did not speak Greek, so not too much emphasis should be placed on the modern connotation of the word 'barbarian'. Egyptian practises were very different and alien to the Greeks, as was their religion. On the other hand, Egypt was an ancient civilisation and was portrayed in the ancient sources (i.e., Herodotus, Diodorus and Strabo) as a great old and wise nation that, to the Greeks, was the cradle of civilisation.

What happened to Naukratis?

Naukratis archaeological site

The vagaries of the Nile tributaries and the competing presence of Thonis-Heracleion, plus the increasing influence of the port of Alexandria after 331 BC, gradually led to the decline of what had been one of Egypt's most important ports in antiquity. Despite this, Naukratis remained a successful centre of commerce, acting as a conduit for goods arriving at Thonis-Heracleion, and later at Alexandria, destined for inland and for Egyptian products, including its own manufactured goods destined for exchange abroad. Naukratis increased in importance over Thonis-Heracleion after a major weather event, either a tsunami, earthquake, or a combination, partially destroyed the latter city in the 2nd century BC. Naukratis continued to function until the 7th century AD. Islamic burials have been found from this period at the site. After the 7th century, Naukratis was gradually subsumed by the modern villages of Kom Gi'eif, el-Nibeira and el-Niqrash and only rediscovered in 1884 by archaeologist W.M. Flinders Petrie.

References

Herodotus, 2003 (latest revision),Histories, translated by Aubrey de Salincourt, Penguin Books, London.

Johansson, N., Life in Naukratis https://www.academia.edu/1052192/Life_in_Naukratis

Muller, A., 2000, Naukratis: Trade in Archaic Greece, Oxford UniversityPress, Oxford.

Roebuck, C., 1950, 'The Grain Trade between Greece and Egypt',Classical Philology, Volume 45, No. 4, pp. 236-247.

Roebuck, C., 1951, 'The Organisation of Naukratis', Classical Philology,Volume 46, No. 4, pp. 212-220.

Strabo, 1932,The Geography of Strabo, Volume VIII, translated byHorace L. Jones, The Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann Ltd.,London

Tsetskladze, G.R. and de Angelis, F. (eds.), 2003,The Archaeology of Greek Colonisation, The Oxford Committee for Archaeology, Oxford.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC

19: The First Trade Wars 580 - 265 BC 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution