Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

Trade, Conflict, and the Sicilian Wars (580-265 BC)

Investigating the first trade wars, the centuries-long struggle for Mediterranean dominance between Etruscans, Greeks, and Carthaginians. This article details their trade networks, strategic alliances, and the brutal Sicilian Wars (580-265 BC) that shaped ancient history and laid the groundwork for the rise of Rome.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-21 | Last Updated 2025-07-21 | Ancient Trade Routes in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 2,975 times

Agrigento (ancient Akragas), Sicily, Monumental Greek architecture

Sicily, the Ancient Mediterranean's Contested Crossroads

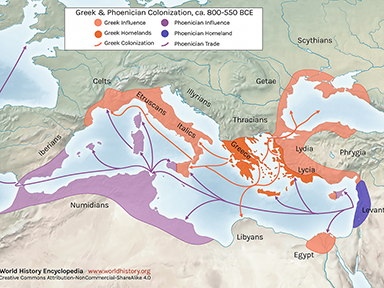

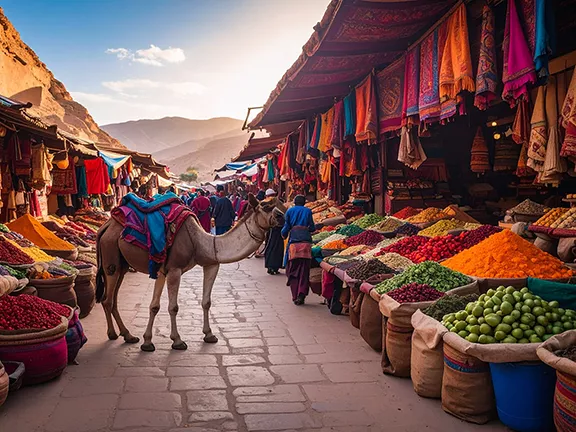

Imagine the Mediterranean Sea in the 6th century BC, not as a calm expanse, but as a crowded, hectic, marine highway. Warships, cargo vessels large and small, and coastal traders navigated its waters, all part of the complex, ceaseless dance of commerce. During this era, three mighty civilizations—the Etruscans, Greeks, and Carthaginians—battled for control of valuable maritime trade routes and strategic territories. Their interactions shaped the course of ancient history, setting the stage for future geopolitical conflicts. From the Etruscan bases in central Italy, the burgeoning Greek colonies in Sicily and Southern Italy, and the dominant Carthaginian presence in North Africa, these civilizations extended their influence across the sea.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Empires of the Mediterranean Sea: Profiles of Power and Commerce

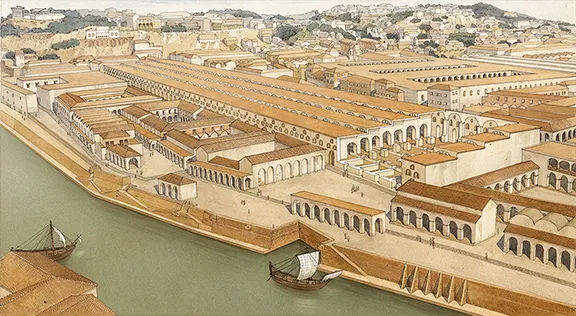

Solunto - Carthaginian port northern Sicily

The Greeks: Colonizers and Innovators

By 600 BC, Greek city-states had already established an impressive network of colonies, spreading Hellenic culture and commerce across the Mediterranean. They founded over 500 settlements, with a staggering 40% of all Greeks living in these new territories by 500 BC.

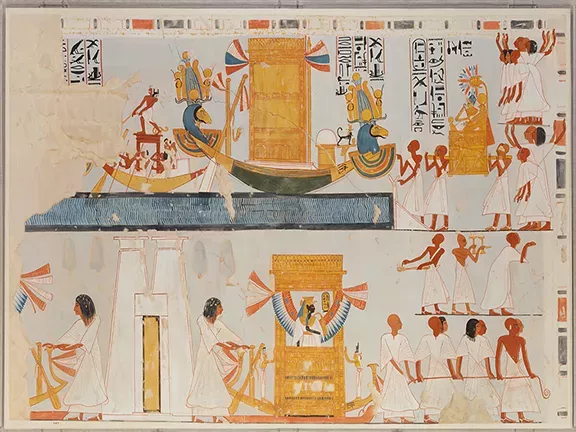

Magna Graecia (Greater Greece), encompassing Sicily and Southern Italy, became a "second Greece," with key cities like Cumae, founded about 1050 BC on the Italian mainland, Syracuse, founded by Corinth in 733 BC, and Gela, founded in 688 BC, flourishing across Sicily. Beyond Italy, Greek influence extended to Thonis-Heracleion in Egypt after the 8th century BC, Massalia (modern Marseille) in France, founded by Phocaean Greeks around 600 BC, Empuries in the Iberian Peninsula founded by Phocaeans from Massalia around 575 BC, Naucratis in Egypt, established in 615 BC, and numerous colonies around the Black Sea. Thonis-Heracleion was one of the earliest, if not the very first, overseas colony established by the Greeks as they emerged from the 'Greek Dark Ages' which followed the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization and the Bronze Age generally.

These colonies served as vital hubs for trade, exporting luxury goods like fine pottery, wine, olive oil, metalwork, and textiles, while importing essential resources such as timber, metals (including tin), and agricultural products like grain and dried fish. The Greeks were keen seafarers; their myths, filled with tales of exploration like Jason and the Argonauts, reflected their adventurous spirit. Greek merchant ships, though typically smaller in the archaic period, measuring around 15-20 meters long with a 10-20 ton capacity, were efficient vessels propelled by sails and oars. For warfare, they developed formidable vessels like the pentekonter, approximately 30 meters long with 50 oars, and, crucially, the trireme, measuring around 35-36 meters long and 5.5 meters wide, with 170 rowers. The trireme became the backbone of their fleet, particularly after the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC.

Greek colonization represented a profound demographic and economic shift in the Mediterranean, transforming them from localized city-states into a pan-Mediterranean commercial and military force. The places selected for colonization were carefully chosen, not only for their potential business advantages but also for offering security from raiders. This calculated approach, rather than spontaneous migration, resulted in the formation of a "Magna Graecia" where Greek culture and urban landscapes flourished. This extensive and intentional expansion inevitably brought them into direct competition and conflict with existing powers like the Etruscans and Carthaginians, as they sought to integrate these new territories into their trade networks and assert their influence. The economic imperative directly underpinned their geopolitical strategy.

Carthage: The Punic Maritime Hegemon

Carthage, founded as a Phoenician colony from Tyre in the 9th century BC, rose to become one of the most powerful states in the Mediterranean by the 3rd century BC. After Tyre's conquest by the Babylonians in the early 6th century BC, other Phoenician colonies in the west turned to Carthage for protection against their Greek rivals, solidifying Carthage's leadership. With a powerful fleet, Carthage dominated trade across the western Mediterranean, extending its influence from North Africa to western Sicily, Sardinia, and southern Spain. Their chief external policy was to control these vital sea routes within their area of influence.

Carthaginian merchants engaged in lucrative Trans-Saharan trade, bringing gold, slaves, ivory, and salt from tropical Africa. They also exported manufactured goods, agricultural produce, and salt fish, with Carthaginian amphorae found as far away as Corinth, Greece. The dispersal of "Carthaginian Stone," a prized red gemstone, probably a garnet, throughout Europe and beyond demonstrates the diversity and extensive reach of Carthaginian trade. Carthage's formidable naval and territorial power stemmed directly from its highly organized and diversified trade networks, particularly its control over strategic raw materials and lucrative Trans-Saharan routes, making it a formidable rival for any aspiring maritime power.

Carthage's evolution from a trading post to a regional hegemon, offering protection to other Phoenician colonies, marked a critical shift in the power dynamics of the Western Mediterranean. Initially, Carthage was a Phoenician trading settlement. However, as its parent city Tyre faced threats from Babylon, Carthage stepped into a vacuum, becoming a protector for other Phoenician colonies against Greek competition. This move transformed Carthage from a purely commercial entity into a formidable geopolitical power with a clear strategic agenda: to control sea routes and counter Greek influence. This proactive assertion of power directly contributed to the escalating conflicts of the 6th century BC.

The Etruscans: Italian Seafarers and Traders

The Etruscan civilization flourished in central Italy, roughly corresponding to modern Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, with influence extending to the Po Valley and Campania. Around 600 BC, a league of twelve Etruscan city-states formed a loose confederation. Although no complete consensus exists on the exact composition, frequently cited cities include Arretium, Caisra, Clevsin, Curtun, Perusna, Pupluna, Veii, Tarchna, Vetluna, Volterra, Velzna, and Velch in northwestern and central Italy. They also controlled Rome until 510 BC, a period during which Rome began to develop into a populous city.

Etruscans were active sea traders, leveraging their rich natural resources, especially copper and iron. They exported iron, grain, pine nuts, olive oil, and wine, with evidence of their wine amphorae found along the Etrurian coast, Provence, Alicante, and even Sicily and Naxos. Their distinctive black, glossy pottery called bucchero also found markets across the Mediterranean, including Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Carthage. In exchange, they received luxury goods like ivory from Egypt, amber from the Baltic, and pottery from Greece. Etruscan trade wasn't centrally administered but rather operated through independent towns, often via specialized coastal trading areas known as emporia, such as Pyrgi and Gravisca. This decentralized approach, however, still connected them to a vast exchange network. Etruscan culture was significantly influenced by Greek art, with Greek artists settling in Etruscan towns like Veii and Cerveteri in the 6th century BC, introducing red and black pottery techniques.

The Etruscans, while maintaining a decentralized economic structure, demonstrated strategic adaptability by forming crucial alliances and integrating foreign artistic and commercial practices, displaying a nuanced approach to power projection in a highly competitive maritime environment. Increased competition from Greek and Carthaginian traders pushed the Etruscans to seek new markets inland, even beyond the Alps to the Celts. This economic pressure also solidified their alliance with Carthage. While the Etruscans were already established traders, known for their metals and pottery, the rising maritime power of the Greeks and Carthaginians created intense competition. This external pressure forced the Etruscans to adapt, not only by seeking new land-based markets but also by strengthening their naval and commercial alliances, most notably with Carthage, to protect their existing interests.

Trade, Territory, and Tensions in the Central Mediterranean

Motia showing typical Carthaginian masonry

The central Mediterranean Sea transformed into an arena of fierce competition. While trade fostered cultural exchange—Greek artists settling in Etruscan towns, influencing pottery styles, and Carthaginian textiles finding their way to Athens—it also laid the groundwork for conflict. The Etruscans and Carthaginians formed an anti-Greek alliance, recognizing a shared rival in the expanding Hellenic presence.

Overlapping commercial interests inevitably led to friction. Sicily, with its fertile lands and strategic position, emerged as the primary flashpoint. Greek colonies like Syracuse and Gela thrived on the island, directly challenging Carthaginian claims in the west and Etruscan ambitions for wider trade dominance. The layering of different-era anchors, from prehistoric stone anchors to 7th century AD iron anchors, found near wreck sites like the one at Santa Maria del Focallo, suggests centuries of continuous, and likely contested, maritime activity in the area.

This concentration of competing interests on one island meant that both Greeks and Carthaginians considered control over Sicily strategically essential to project their power and secure their trade routes across the entire Mediterranean. Sicily became the primary theatre of conflict.

As the 6th century BC progressed, the scramble for control over trade routes and resources intensified, pushing these powers from economic rivalry into open military confrontation. The sea became the setting for some of the most violent contests. Far from fostering peace, the intense economic interdependence and competition for control of vital trade routes and resources in the 6th century BC Mediterranean directly led to geopolitical instability, forcing alliances and escalating rivalries into open warfare among the major powers.

The data shows that trade was extensive, even between rivals, yet this economic interdependence did not prevent conflict. Instead, it fuelled it by creating overlapping claims and competition for strategic resources and markets. The alliance between Etruscans and Carthaginians against the Greeks is a clear example of how economic rivalry translated into military strategy.

The First Trade Wars: Naval Engagements and Battles that Shaped the Mediterranean

Elymian town of Segesta

The Battle of Alalia (c. 540-535 BC): A Pyrrhic Victory

One of the most defining naval clashes of this period was the Battle of Alalia, fought off the coast of Corsica. Phocaean Greeks, who had established colonies like Massalia and Alalia, found themselves challenged by a combined Etruscan and Carthaginian fleet. Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, famously described the outcome for the Greeks as a "Pyrrhic victory"—a win so costly it felt like a defeat.

The Greeks, with 60 ships, likely pentekonters (ships with 48 oars), as the more advanced triremes had not yet become primary warships, faced an allied fleet twice their size. Despite being outnumbered, the Phocaeans employed creative tactics, including the bronze ram and the diekplous, a manoeuvre designed to break through enemy lines.

While the Phocaeans drove off the allied fleet, they lost nearly two-thirds of their own ships, with the surviving vessels severely damaged. Herodotus' description of the Greek "victory" at Alalia reveals that even a technical 'victory' came at a crippling cost. This suggests that the naval technology and tactics of the time, while capable of inflicting damage, might not have been conducive to total fleet destruction, leading to prolonged, attritional struggles for control rather than swift, decisive outcomes.

This pattern of costly engagements forced strategic realignments and continued competition, rather than a clear resolution of dominance, setting a precedent for the centuries of rivalry that followed. This brutal encounter reshaped the balance of power in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Realizing they could not withstand another attack, the Greeks evacuated Corsica, which the Etruscans then captured, while Carthage solidified its hold on Sardinia. The Battle of Alalia, despite its devastating cost to the Greeks, served as a critical catalyst for naval innovation, particularly in the refinement of the trireme as a specialized warship, demonstrating how intense conflict directly drove advancements in ancient military technology and strategy.

Sicilian Struggles: Ongoing Greek-Carthaginian Clashes

After Alalia, Sicily remained a consistent battleground. For centuries, Greeks and Carthaginians fought intermittently for control over Sicilian territory and the allegiance of the island's indigenous populations. An earlier notable confrontation occurred in 580 BC near Lilybaeum in Sicily, where Phoenician cities (Motya, Panormus, Solus) allied with the Elymians to defeat Greek forces from Selinous and Rhodes. This marked the first recorded instance of such a combined effort against the Greeks in Sicily. The Etruscans also faced challenges from Greek colonies in southern Italy, leading to confrontations such as the Battle of Cumae in 474 BCE. These conflicts collectively underscore the pervasive nature of the competition, where economic rivalries frequently escalated into armed confrontations that reshaped the balance of power. V. The Sicilian Wars and the Pyrrhic War: Three Centuries of Conflict The struggle for dominance in the Mediterranean, particularly over the fertile and strategically vital island of Sicily, continued for three centuries beyond the initial clashes of the 6th century BC. This prolonged rivalry between Carthage and the Greek city-states, primarily Syracuse, manifested in a series of brutal conflicts known as the Sicilian Wars or Greco-Punic Wars, culminating in the Pyrrhic War, which drew Rome into the fray. These wars, spanning from 580 BC to 265 BC, represented a continuous struggle for control over trade routes, resources, and regional hegemony.

The First Sicilian War (480-474 BC)

This initial major clash witnessed Carthage launch a large-scale invasion of Greek Sicily, possibly in a coordinated effort with the Persian invasion of mainland Greece. The Carthaginian fleet, led by Hamilcar, reportedly suffered significant losses due to poor weather en route to the island. Despite this, they landed a formidable force. The Greek city-states, under the combined leadership of Gelon, tyrant of Syracuse, and Theron, tyrant of Agrigentum, met the Carthaginian army at the Battle of Himera in 480 BC. The Greeks achieved a decisive victory, routing Hamilcar's forces. Hamilcar himself was either killed in battle or, in shame, committed suicide. This defeat prompted significant political changes in Carthage, with the old nobility replaced by a new republican government, though the king retained limited power. As a result, Carthage paid reparations to the Greeks and refrained from intervening in Sicilian affairs for the next 70 years, fostering Greek cultural and economic prosperity on the island.

The Second Sicilian War (410-405 BC)

After a period of relative peace, tensions flared again, leading to the Second Sicilian War. This conflict erupted when the Elymian city of Segesta, embroiled in a territorial dispute with Selinus, appealed to Carthage for assistance in 410 BC, following Athens' failed Sicilian Expedition in 413 BC. Carthage, under the command of Hannibal Mago, responded with a large-scale invasion of Sicily. Hannibal Mago systematically attacked Greek cities, sacking and destroying Selinus in 409 BC, and then Himera, which was never rebuilt. In a brutal act, he reportedly sacrificed 3,000 Greek prisoners at Himera, a grim retribution for his grandfather Hamilcar's death, who fell in the first war. The war involved intense naval battles, sieges, and land skirmishes, yet ultimately concluded without a decisive resolution, setting the stage for further confrontations. During this crisis, Dionysius I rose to power as tyrant of Syracuse in 405 BC. Carthaginian general Himilco besieged Gela and defeated Dionysius, but a devastating plague miraculously saved the Greeks by ravaging Himilco's army. A subsequent peace treaty left Carthage in direct control of western Sicily, with newly conquered cities paying tribute.

The Third Sicilian War (398-392 BC)

Dionysius I of Syracuse, having consolidated his power, launched a new offensive in 398 BC, aiming to reclaim Carthaginian territories on the island. His forces captured the key Carthaginian island fortress of Motya, a siege that marked the first recorded use of catapults in Greek warfare. Despite initial Greek successes, Carthaginian forces under Himilco recaptured Motya in 396 BC and besieged Syracuse itself. Once again, a deadly plague struck the Carthaginian camp, forcing Himilco to withdraw and sparing Syracuse from capture. The war concluded with a peace treaty in 392 BC, which formally recognized Carthaginian control over the area west of the Halycus River, while Dionysius gained lordship over the Sicel lands in central Sicily.

The Fourth Sicilian War (383-378 BC)

Dionysius I, emboldened by his previous campaigns, launched another attack on Carthage. This war, though historical accounts are sparser for this conflict, resulted in significant setbacks for Syracuse. Dionysius suffered a crushing defeat at Cronium and was forced to pay a large indemnity to Carthage, losing territory in the west. The Halycus River was re-established as the frontier between Carthaginian and Greek territories, solidifying Carthage's hold on western Sicily.

The Fifth Sicilian War (345-339 BC)

Internal political turmoil and the persistent Carthaginian threat prompted Syracuse to appeal to its mother-city, Corinth, for aid. Corinth responded by sending Timoleon, a skilled general, to Sicily in 344 BC. Timoleon swiftly defeated the existing tyrants, Dionysius II and Hicetas, establishing a more democratic government in Syracuse. His greatest triumph came at the Battle of the Crimissus in 339 BC, where his vastly outnumbered Syracusan army of approximately 5,000 infantry decisively routed a massive Carthaginian force, reportedly numbering 70,000 men, under Hasdrubal and Hamilcar. A sudden storm during the battle further aided the Greeks, dramatically turning the tide against the Carthaginians and leading to heavy losses among their wealthiest citizens. The subsequent peace treaty reaffirmed Carthaginian control west of the Lycus River but brought years of stability and prosperity to Greek Sicily under Timoleon's leadership.

The Sixth Sicilian War (311-306 BC)

Peace proved fleeting after Timoleon's death. Agathocles, a new tyrant of Syracuse, renewed hostilities with Carthage in 311 BC. After suffering a defeat and being besieged in Syracuse, Agathocles embarked on a daring and unexpected strategy: he broke through the blockade to invade Carthage's North African homeland in 310 BC. This bold move caused panic in Carthage, which was largely unprepared for a direct invasion of its territory. Agathocles achieved initial successes, pillaging the countryside, but eventually abandoned his army in Africa and returned to Sicily in 307 BC. The war concluded with a peace treaty in 306 BC, which largely restored the status quo ante bellum, with Carthaginian power in Sicily again restricted to the area west of the Halycus River. Agathocles, however, solidified his rule over Greek Sicily and even assumed the title of king, demonstrating that Carthage could indeed be challenged on its home soil—a lesson Rome would later exploit.

The Seventh Sicilian War (306-265 BC)

This period marks the final phase of the Greco-Punic Wars, leading directly into the First Punic War with Rome. After Agathocles' death in 289 BC, Sicily plunged into a period of anarchy, with Greek cities unable to cooperate effectively. Carthage seized the opportunity, rapidly expanding its influence eastward across the island. The Mamertines, former Syracusan mercenaries, seized control of Messana, a strategically vital city controlling the Strait of Messina. In 265 BC, Hiero II, the new tyrant of Syracuse, besieged Messana. The Mamertines, in a desperate move, appealed first to Carthage, which sent Admiral Hannibal to garrison the city, effectively gaining control of the Strait. However, the Mamertines then sought assistance from the rising power of Rome, prompting Roman intervention and ultimately igniting the First Punic War in 264 BC, a conflict that would decide the fate of the entire Mediterranean.

The Pyrrhic War (280-275 BC)

Intertwined with the later Sicilian Wars, the Pyrrhic War saw a new major player enter the complex geopolitical landscape: Pyrrhus, the ambitious King of Epirus. Invited by the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italy to aid them against the expanding Roman Republic, Pyrrhus brought his professional mercenary army, complete with war elephants, to Italy in 280 BC. He achieved initial victories against the Romans, but at a heavy cost, giving rise to the term "Pyrrhic victory" for a win achieved at too great a price.

Worn down by these costly battles, Pyrrhus shifted his focus to Sicily in 278 BC, responding to pleas from Greek cities like Syracuse, Agrigentum, and Leontini to help them expel the Carthaginians and their tyrants. He achieved significant successes, capturing most Carthaginian strongholds on the island, including Motya, Eryx, and Panormus, leaving only Lilybaeum in Carthaginian hands. However, the Carthaginians fiercely resisted at Lilybaeum, and Pyrrhus's Sicilian allies eventually revolted against his increasingly autocratic rule. Facing a stalemate in Sicily and renewed pressure from Rome, Pyrrhus returned to Italy in 275 BC, where the Romans finally defeated him. His departure left southern Italy under Roman hegemony and Sicily as a contested prize between Rome and Carthage, directly setting the stage for the Punic Wars. Notably, during this period, Rome and Carthage, despite their long-standing rivalry, even formed a temporary alliance against Pyrrhus, highlighting the shifting allegiances in the face of a common threat.

Dominating the News

Selinunte - Greek city, southwestern Sicily

Although the Greco-Punic Wars no doubt dominated the news of the day, maritime trade throughout the Mediterranean not only continued but flourished. In the middle of these wars, about 325 BC, men such as Pytheas were forging new routes to new markets.

The two main trading nations throughout this period were the Greeks and the Carthaginians. Only with the emergence of Rome as an Empire and a significant naval power did the Mediterranean become a united trading entity.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean

1: Overland Trade Routes to the Mediterranean 2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea

2: First Voyages on the Mediterranean Sea 3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC

3: Mesolithic Voyages to Malta c 6500 BC 4: Neolithic Maritime Networks

4: Neolithic Maritime Networks 5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean

5: Bronze Age Maritime Networks in the Mediterranean 6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age

6: Morocco to Iberia during the Bronze Age 7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans

7: Areas of Influence Mesolithic to Romans 8: The Tin Roads

8: The Tin Roads 9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC

9: The Karum of Kanesh c 1920 - 1850 BC 10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies

10: Mediterranean Bronze Age Economies 11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages

11: Postal Services during the Bronze and Iron Ages 12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars

12: The Start of Mediterranean Trade Wars 13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC

13: The Voyage of Wenamun c 1075 BC 14: From Trading Post to Emporium

14: From Trading Post to Emporium 15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion

15: The Greek Emporium of Thonis-Heracleion 16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis

16: The Greek Emporium of Naukratis 17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries

17: The Greek Emporium of Empuries 18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt

18: Canopus in Ancient Egypt 20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas

20: Exploring new Trade Routes with Pytheas 21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution

21: Corinthian Helmet Distribution