Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

Iron Age shipwrecks of Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC

The iron age shipwrecks of the Tanit and Elissa, found in deep water off Ashkelon, Israel, were the first ancient deep sea wrecks to be surveyed.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-12-19 | Last Updated 2025-01-16 | Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 2,780 times

Outline of the Tanit wreck

Where were the Tanit and Elissa wrecks found?

Both the Tanit and Elissa wrecks were found at a depth of 400 metres about 61 kilometres off Ashkelon, Israel, 2 kilometres apart. In 1997, the United States nuclear research submarine was conducting a search for an Israeli submarine lost in the 1960s when its search sonar found three shipwrecks off Egypt and the Gaza strip. Two of the wrecks carried amphorae. The third proved to be an 18th or 19th century AD sailing ship.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

About the wreck site

Outline of the Elissa wreck

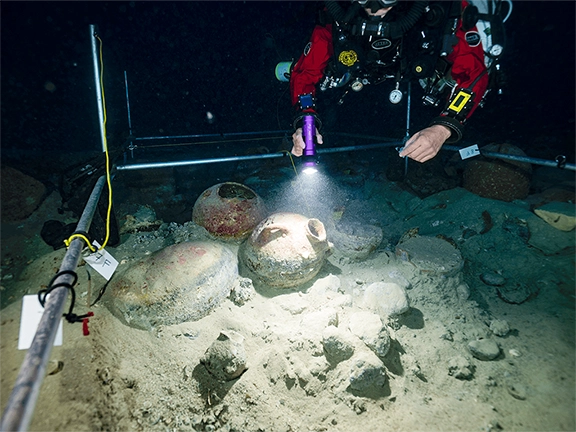

Both of the amphorae carrying ships lie upright on the seafloor at a depth of 400 m in a depression formed by the scour of bottom currents.

Who excavated the Tanit and Elissa shipwrecks?

In 1999, a follow-up expedition was conducted in the area in hopes of relocating the two amphora wreck sites to determine their exact age and origin. The support vessel for this effort was the Northern Horizon, a converted British deep-sea trawler. The expedition was led by Robert D. Ballard, an American retired Navy officer and a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island most famous for his discovery of RMS Titanic and the German battleship Bismarck.

The Northern Horizon carried a remote vehicle operating system called Medea/Jason and the DSL-120 side scan sonar used to produce both sonograms of the ocean floor as well as bathymetric maps.

The Medea/Jason ROV system is equipped with advanced robotics and control technology ideally suited for deepwater archaeology.

When did the Tanit and Elissa wrecks sink?

The God Tanit

Both wrecks sank at the same time about 750 BC. and were given the nicknames, Tanit and Elissa.

Tanit was protector of Phoenician seafarers, and was the iron age successor of the leading Canaanite goddess Astarte and "Ashera of the Sea."

Elissa was a Tyrian princess and sister of the Tyrian king Pumiyaton. She fled from mainland Phoenicia to Cyprus and picked up a crew of Phoenicians with whom she sailed for the western Mediterranean. According to legend she then went on to found Carthage.

How were Tanit and Elissa built and what were their dimensions?

Any organic material from the wrecks has long been eroded or is still buried beneath the top layers of cargo. Microbathymetry provides the most precise measurements of the two shipwrecks. The contours of their cargoes are in the shape of a ship, outlining the forms of their long vanished hulls. The cargo of Tanit measures 4.5 metres wide by 11.5 metres long, for which we would estimate an overall width of about 6.5 metres and a length of about 14 metres. The cargo of Elissa is 5 metres wide and 12 metres long for an estimated size of the ship of about 7 metres wide and about 14.5 metres long.

The ships were estimated to be 25 tons when fully loaded. The Tanit and Elissa were wide at the beam, about three times as long as they were wide. They are not as slim as Phoenician ships depicted in relief with horse head prows and known in Greek sources as hippoi ("horses") but more like what the Greeks called gauloi, or "tubs."

What were the Tanit and Elissa cargoes?

The Goddess Elissa

Both ships were carrying amphorae. Tanit had 385 visible amphorae, 16 of which were recovered, and Elissa had 396 of which 7 were recovered. This represents the top two tiers of the cargo, and it is not known what remains below.

Other artefacts recovered from the Tanit were: 2 cooking pots and 1 handmade bowl.

Other artefacts recovered from the Elissa were: 1 quarter amphora, 4 cooking pots, 1 mortarium, 1 decanter, 1 incense stand, 6 ballast stones and 1 broken bowl.

The amphorae were once filled with wine and the estimated tonnage of cargo per ship was 10 tons.

Where did the Tanit and Elissa cargoes come from?

The amphorae from both wrecks have been studied extensively and it is worth going into some detail.

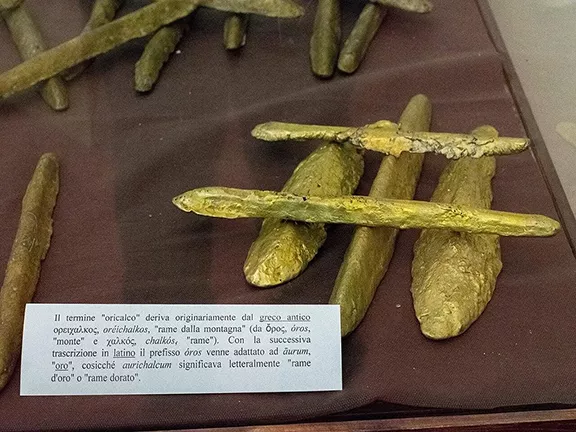

The amphorae have a slightly wasp-waisted body, a sharp shoulder, and a medium high-necked rim thickened at the top and are well known from land excavations in Israel and Lebanon. On land, these vessels are commonly found in eighth-century contexts such as at Megiddo, Hazor, and Tyre. While there may be some ninth-century examples at Hazor and Megiddo, the distribution is heavily weighted toward the middle to end of the eighth century.

Within the eighth century, there is a geographically limited distribution of these amphoras. Hazor and Megiddo have more than 60 whole forms, in addition to rim fragments. Tyre and Sarepta, while not possessing many whole forms, have hundreds of rim fragments. Apart from these four sites, no other site has more than 10 preserved examples. This narrowly defined distribution, basically the Phoenician coast, shows the inland use of these containers is quite rare. This type of amphora however is common at Carthage with a few examples showing up on Cyprus.

A possible destination for the cargoes carried by the Tanit and Elissa was the newly founded (814 BC) Phoenician colony at Carthage. The early Carthaginian colonists, many of them Tyrians according to founding legends, imported this type of transport amphora from the Levant. In Carthage, complete jars have been found among mortuary offerings in tombs and graves as well as in habitations within the city. In one room alone the fill beneath the floor produced rim sherds representing thirty examples of this amphora.

Why this design of amphora was used predominantly for maritime trade may be explained by the shape of the handles that are perfectly designed for the guide ropes used to secure a shipborne cargo. While impractical for terrestrial transport and pouring, these amphorae were perfect as purpose-built maritime containers.

Another indication of their use for maritime transport purposes is the standardization of the amphorae, the deviation was less than 2 cms in height and 1 cm in width. These exacting tolerances were necessary for intricately stacking more than 400 amphoras in the hold of a ship. If this standardization is representative of the hundreds of amphoras still on the wrecks, the picture of standardized production is even more remarkable.

This narrow range also indicates considerable standardization in manufacture.

Now the researchers turned to the origin of the amphorae. The ports at which many of these amphora are found have a tradition of substantial pottery production. At Sarepta, several kilns have been excavated, and at Tyre, while no kilns were found in the extremely limited exposures of that excavation, some kiln wasters from this very type of amphora were discovered. Finally, the petrographic profile of these jars is consistent with the Phoenician coast, arguing for a manufacturing base at one of the ports on that coast, probably Tyre.

Inspection of the 21 amphoras recovered from Tanit and Elissa indicates that all of the jars had once been lined with resin. Analysis of the residue from one amphora indicated the contents had been wine. This analysis along with the presence of resin lining in the other amphoras examined makes it clear that many, if not all, of the nearly identical amphoras on board the two shipwrecks contained wine.

The best clue as to the origin of the wine within the amphorae comes from the bible. Ezekiel says that fine wine was transported overland from faraway places such as Izalia near Mardin in Anatolia to Damascus where wines from Helbon, a city nearby, joined the convoy bound for Tyre. Interestingly, the containers, pithoi, used to carry wine overland, were ten times the capacity of the amphorae used for maritime transport. At some point, probably in Tyre, the wine was decanted into the smaller amphorae.

The personal effects and shipboard equipment also cast light on the origin of the wrecks.

The six cooking pots recovered from both wrecks were, stylistically, similar to the 8th century BC cooking pots found at Arqa on the Lebanese coast. It is known that Phoenician ships of this period had cooking facilities in a cabin in the stern of the vessel.

The handmade bowl found on the Tanit apparently came from Egypt. It was probably picked up by a member of the crew.

The mushroom-lipped decanter is normally found at Phoenician sites in the southern Lebanon and more rarely in areas reached by the Phoenician maritime traders. The design of the decanter, with a sharp shoulder, is typical of forms from the last quarter of the 8th century BC. The mushroom-style rim, whether on jug, juglet, or decanter, was the "calling card" of Phoenicians from Tyre to the Pillars of Hercules.

The small ceramic incense stand recovered from the galley of Elissa falls very much in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age traditions of terracotta incense stands designed to be handheld. Typically, they were used to offer aromatics to the gods.

The mortarium was found on the port side of Elissa. A mortarium is a bowl, in which various foodstuffs would be ground. On land, this form is generally found in contexts dating to the 7th c BC and later. Mortaria are found over a time span lasting more than a millennium, and throughout this period, they appear to have been made at only a very few production sites. This 8th c BC example closely matches the petrographic profile of the majority of later mortaria, a provenience most closely linked to the northeast corner of the Mediterranean, at sites such as Ras al-Bassit in northern coastal Syria. The use of deep bowls as mortars for grinding condiments was known in Cilicia at Tarsus as early as the 8th c century BC Another eighth-century mortarium has been found in the Phoenician site of Horbat Rosh Zayit in Galilee. There too it appears alongside torpedo-shaped amphorae. The Elissa mortarium seems to be one of this early eighth-century form, which marks the beginning of specialized mortarium production.

Where did the Tanit and Elissa come from and where were they going?

It is likely that Tanit and Elissa were two ships in a convoy setting off from one of the Phoenician city ports, probably Tyre. Their destination was somewhere on the coast of north Africa, the new colony of Carthage, or possibly Egypt.

If Egypt were the intended destination of the Tanit and the Elissa, they seemed to be on or near a direct route between Ashkelon and the Delta, most likely not hugging the coast as they sailed. These north Sinai coastal waters are among the most treacherous in the eastern Mediterranean.

Why did the Tanit and Elissa sink?

We will never know why the Tanit and Elissa sank. We can speculate that they were overcome by a strong wind, causing the vessels to capsize. This southeastern part of the Mediterranean is notorious for a wind known as the ruah qadim, an unexpected and fierce wind that blows across the desert from the east.

Where did the crew of the Tanit and Elissa shipwrecks originate?

Evidence from the two shipwrecks provides clues as to the home base of the crew. At the stern end was found a ceramic mortarium for grinding condiments and cooking pots for one-pot stews, replenished regularly with fresh-caught fish and other seafood. (The petrographic profile of the cooking pots is consistent with a locale in Lebanon, with best parallels at Tell 'Arqa.) The incense burner is in the Late Bronze Age tradition, continued through the Iron Age. It is similar to one being held aloft by a Canaanite sea captain, depicted in a 14th-century BC Egyptian wall relief from the tomb of Kenamun. In his other hand the captain holds a libation cup filled with wine. Both the incense and drink offerings were being offered probably to Ba'l Saphon for the safe arrival in Egypt.

The incense and wine offerings on our Phoenician ships proved to be less efficacious.

The best clue as to the crew's origin comes from the wine decanter with mushroom-shaped lip-the calling card of the Phoenicians from the Levant to the Pillars of Hercules.

The Tanit and Elissa were, then, Phoenician ships manned by Phoenician crews and mainly loaded with a single commodity: fine wines from elsewhere decanted into and transported abroad in Phoenician amphoras.

Political situation at the time

In 750 BC, the Middle East was a complex and dynamic region undergoing significant political shifts. The Neo-Assyrian Empire, which had dominated for centuries, was in decline, facing internal instability and external threats. The Neo-Babylonian Empire, under the leadership of Marduk-apla-iddina II, was consolidating its power, taking advantage of Assyria's weakness. Egypt, under the 22nd Dynasty, was a relatively stable kingdom but faced challenges from internal rivalries and external pressures. In the Levant, several smaller kingdoms and city-states, such as Israel, Judah, and Aram, were vying for power and influence, often caught between the larger empires.

The political situation in the central Mediterranean around 750 BC was characterized by a patchwork of small, independent city-states rather than large empires. In Greece, this period saw the rise of the polis, a self-governing city-state with its own laws, military, and currency. These poleis ranged from monarchies and oligarchies to early forms of democracy.

The Phoenicians, skilled seafarers and traders, established colonies throughout the Mediterranean, including Carthage in North Africa, which would eventually grow into a powerful rival to Rome.

Overall, the central Mediterranean around 750 BC was a dynamic and complex region marked by political diversity and shifting power balances. The rise of the polis in Greece and the decline of the Neo-Assyrian Empire set the stage for future conflicts and alliances that would shape the course of history.

References

Ballard, Robert & Stager, Lawrence & Master, Daniel & Yoerger, Dana & Mindell, David & Whitcomb, Louis & Singh, Hanumant & Piechota, Dennis. (2002). Iron Age Shipwrecks in Deep Water off Ashkelon, Israel. American Journal of Archaeology. 106. 151. 10.2307/4126241.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC 2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC

2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC 4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC

4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC 5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC

5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC 6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC

6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC 7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC

7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC 8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period

8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period 9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period

9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period 10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC

10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC 11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC

11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC 12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC

12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC 13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC

13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC 14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC

14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC 15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC

15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC 16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC

16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC