Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

The Bajo de la Campana Phoenician period shipwreck c 600 BC

The cargo from the Bajo de la Campana Phoenician period shipwreck compared to artifacts found at known Phoenician ports in Andalucia, Murcia, Catalonia, and Ibiza, has allowed the last voyage of the ship to be recreated.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-01-1 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 3,969 times

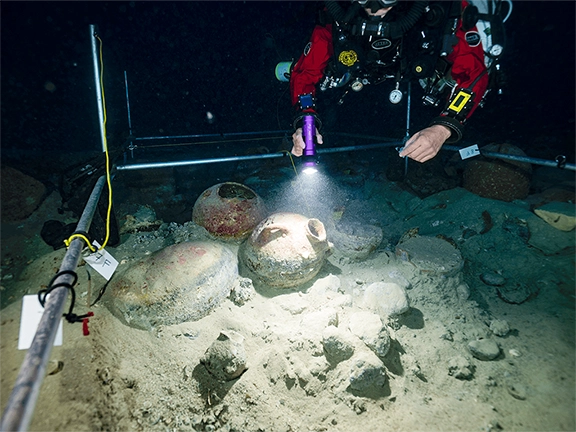

Surveying the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck

Where was the Bajo de la Campana wreck found?

Bajo de la Campana (the Bajo) is a small, submerged basaltic outcropping situated 4 kilometres from La Manga, a thin spit of land separating the Mar Menor, Europe's largest lagoon, from the Mediterranean Sea on the coast of Murcia region.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

About the Bajo de la Campana wreck site

The submerged rock formation ascends from a depth of approximately 16 meters to within a meter of the water's surface, with the seabed sloping gradually away from its base. A significant vertical fracture traverses the rock at its western edge, opening onto the seabed. Prior to excavation, this fissure was filled with a varied assortment of rocks and debris, including boulders, gravel, and finer sediment. The fracture extends beneath the base of the formation, creating a shallow depression also filled with sediment and boulders. Initial discoveries from the site are believed to have originated from this fissure and the associated depression, with substantial additional material recovered during the excavation process. The remaining artifacts were dispersed across an area of approximately 400 square meters on the rocky seabed, extending downwards from the base of the formation.

The excavated wreck site covers an area of 20 metres x 20 metres.

Who excavated the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck?

The Bajo de la Campana site was first discovered in 1958 by salvage divers and later by sports divers. Early divers removed some artifacts that were returned to the authorities in 1979. The Spanish Ministry of Culture arranged an inspection of the site and concluded the artifacts came from three distinct shipwrecks, a late 7th century BC Phoenician period wreck, a 2nd century BC Punic wreck and a 1st century AD Roman wreck. It was not until 2008 that the Institute of Nautical Archaeology launched a full-scale excavation of the site.

When did the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck sink?

Preliminary research indicates that the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck sank in the later part of the 7th century BC.

How was the Bajo de la Campana built and what were its dimensions?

To date (2024) there has been insufficient material recovered from the hull to determine how the Bajo de la Campana ship was built or the dimensions of the ship.

Who were the people who owned and operated the ship?

The mixed nature of the cargo would indicate that the Bajo de la Campana was a large trading ship. Towards the end of the 7th century BC, Phoenician mariners still felt a fealty with their home ports in the Levant, principally Tyre. The merchants that controlled and presumably owned the gauloi, (a large Phoenician trading vessel named by the Greeks for the barrel shaped hull), that sank at Bajo de la Campana could have been Tyrian merchants either based in Tyre or at one of the colonies on the Spanish coast.

Where did the crew of the Bajo de la Campana originate?

It is impossible to say where the crew came from. By 700 BC, trading ships could be manned by crewmembers from many nations, picked up individually at any of the many ports at which the ship called.

What was the Bajo de la Campana ship's cargo?

Two small unguent flasks

The archaeological investigation of the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck proved challenging, with the full extent of its cargo only revealed in the final stages of excavation. The Bajo de la Campana, carrying over four metric tons of cargo, sank while transporting a diverse array of materials. This included both raw materials and finished goods, such as a wide range of Western Phoenician pottery and several unique, non-local items.

The recovered artifacts provide valuable insights into Phoenician trade networks within the Iberian Peninsula and with local indigenous populations. Furthermore, they offer evidence of connections to more distant trading regions. Preliminary analysis of the raw materials holds the potential to shed new light on their origins, processing methods, and the locations of the workshops where they were transformed into valuable trade commodities.

The diverse array of goods and their origins also gives an insight into the long-established overland routes that converged at ports on the coast and the miscellaneous items that were conveyed along those routes.

The presence of luxury goods within the cargo suggests their intended market was the elite class. These items offer a glimpse into the role of such luxury goods in fostering relationships with indigenous communities and facilitating commercial transactions.

Engraved Ivory Tusks from Bojo de la Campana

Ivory Tusks

Sports divers found 13 elephant tusks that they handed over to Spanish authorities in 1979. More recent excavations recovered a further 41 tusks. The species that produced the tusks has not yet been identified but the proximity to North Africa would indicate the tusks are from African elephants. Six of the tusks are inscribed with Phoenician letters. All the inscriptions include a personal name and a declaration of devotion or a request for a blessing. It is possible that the tusks were either destined for or plundered from a sanctuary.

Galena (Lead Ore)

Over one ton of native lead ore in the form of galena, lead sulphide, has been recovered from the wreck site. The presence of wooden staves and basketry found in association with the ore indicated it was being carried in baskets in the hold.

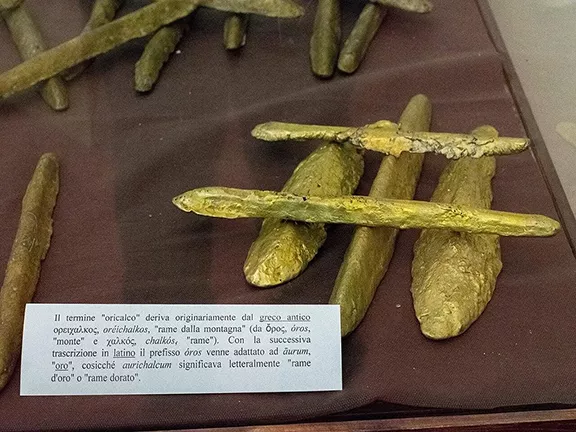

Tin Ingots

The Bajo de la Campana shipwreck was carrying 163 plano-convex tin ingots each weighing between 300 and 2,900 grams with a total all up weight of 170 kilogrammes. Lead isotope analysis revealed that most of the metal came from the same source in northwestern Spain, specifically from the Bilbao-La Corunia region. The remainder came from different deposits in the Ossa-Morena region that extends from east of Lisbon into western Andalucia.

Copper Ingots

The ship was also carrying copper in the form of seven plano-convex ingots with a total weight of 11 kilogrammes. Copper ingots of comparable size and shape have been found in numerous sites across the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands. They are considerably smaller than the 'bun' ingots produced in the eastern Mediterranean through most of the Bronze Age as found on the Antalya Kumluca (1600 - 1500 BC), Uluburun (c 1320 BC), and Gelidonya (c 1200 BC) shipwrecks. This may reflect a local tradition of indigenous copper smelters that predates the appearance of the Phoenicians in the Iberian Peninsula.

Tripod bowl

Ceramics

The Bajo de la Campana shipwreck contained a huge number of ceramic vessel fragments, few were complete. However, meticulous reconstructions from the pieces, have revealed that all the containers were wheel thrown and included, transport amphorae, mortars, flanged plates, bowls, carinated bowls, oil bottles and other small unguentaria, cooking pots, casseroles, urns, and various jugs and pitchers.

Eleven ceramic tripod mortars or bowls, emblematic of Phoenician pottery production in the west, are of a type ubiquitous throughout the western Mediterranean in habitations and graves and, as such, impossible to date.

The ship also carried a few ovoid transport amphorae of a type found at Carthage, Sicily, and Sardinia. The clay of the Bajo de la Campana amphorae was typical of that from Carthage.

Bronze couch legs

Luxury goods

Perhaps the most controversial cargo found on the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck were luxury goods including decorated double-ended boxwood combs, carved ivory hilts for daggers and a small spool shaped ivory ring base. A blue glass disc similar to one found on the Uluburun wreck has been identified as a base for an ostrich egg shell receptacle, fragments of which were also found.

The Bajo de la Campana cargo also included alabaster jars of which many fragments were found.

The ship also appeared to be carrying furniture that would have been the proud possession of an elite merchant or tribal chief. Four hollow bronze legs for a small chair, stool or table were found along with four corner elements from a couch frame. Amongst the wreckage was a small hollow bronze cast forearm clutching a lotus blossom. Several pieces of a bronze cauldron were recovered, as well as the upper portions of two bronze thymiateria or incense burners. The design is reminiscent of thymiateria from Cyprus that have been found in the Levant, Aegean, Malta, Sardinia and on the Iberian Peninsula. There is a nice example in the Huelva Archaeological Museum that was found at the La Joya necropolis.

Altar recovered from Bajo de la Campana

Stone Altar

Finally, the expedition divers found a stone pedestal in three constituent parts, the base and pillar, a volute capital, and an abacus. The design is typical of that of an altar with the recess in the abacus being used for offerings. The dating of this item based on its design elements is very problematic and could be as early as 1000 BC.

Tools and equipment

Amongst the ships gear, the divers found eleven fine grained whetstones of three types. Three are large cylindrical andesite rods that taper from the midpoint to flat ends. All but one of the rest are slim with a fine finish and bevelled edges. They are made from limestone and resemble a late 7th century BC stone, albeit made from sandstone, found at the La Joya necropolis at Huelva. The last whetstone is thin, rectangular, and only one end preserved.

Altogether, fifty-six pan balance weights were recovered from the wreck site. These included 43 cuboid weights, many of which were a bronze shell filled with lead to the desired weight. Whilst the composite weight is known from many site throughout the Mediterranean from the bronze age, this is the first composite collection to be discovered in an iron age context.

Baltic amber

Five lumps of raw, Baltic amber were found on the wreck.

Miscellaneous raw materials

The ship also carried quantities of resin and pitch.

Where did the Bajo de la Campana cargo come from?

The ivory probably originated in North Africa. Where it was acquired by the ship's crew is a mystery. Whilst complete ivory tusks were available for trade at many of the western Mediterranean Phoenician colonies, six of the ones found associated with the Bajo de la Campana wreck had been inscribed which would indicate they had come from a sanctuary prior to being traded.

The galena was subjected to lead isotope analysis that indicated it all came from the same source, either the Sierra Gador or the Sierra Alhamilla in Almeria province, southeastern Spain. The nearest Phoenician port to either Sierra is that at Abdera (Adra).

The tin originated in northwestern Spain. It could have been picked up at one of the ports on the Portuguese coast frequented by Phoenician merchant ships, Santa Olaia (Figuera da Foz), or Lisbon after being transported overland. There is also the possibility that the tin was carried further south, via the Ossa-Morena area, as far as Huelva or Cadiz where it would have been loaded with some of the copper ingots (see below).

Lead isotope analysis of the copper showed that the original ore came from eight, widely spaced, locations, Los Pedroches (Cordoba Province), Linares (province of Jaen), Rio Tinto (Huelva province), Aznalcollar (Seville province), and the Ossa-Morena Zone in Andalucia, and the mining region of Cartagena-Mazarron in southern Murcia. One small fragment of copper originated from the Apliki mine on Cyprus, and three other fragments may have come from Monte Sisini or Calabona on Sardinia. The copper from Cordoba, Jaen and Cartagena could have been picked up by the ship at La Fonteta, a Phoenician port some 50 kilometres north of the wreck site at the mouth of the Rio Segura. That from the remainder of the Andalucian sites probably made its way overland to the port of Huelva. The copper fragments could have been scrap copper from items previously imported into the Iberian Peninsula.

The amber, as the name implies, originated in the Baltic region. It would have been carried down the already ancient Amber Road into central France where it would have been transported down the network of established trading routes into the Iberian Peninsula.

The origin of the ceramic collection is particularly interesting. The transport amphorae were of two types, the first with a distribution pattern from the Atlantic coast of Morocco through to Sicily. This type was manufactured at workshops along the Strait of Gibraltar from the late 8th until the 6th centuries BC. The clay used is typical of that found along the southern Andalucian coast, particularly Cerro del Villar near Malaga. Amphora of this type have been found throughout southern and eastern Spain, including at La Fonteta.

The second type of transport amphorae, fewer in number than the first, were produced at Phoenician potteries in Carthage, Sicily, and Sardinia. They have been found along the Mediterranean coast of Spain, notably Toscanos, about 40 kilometres east of Malaga and on Ibiza. They are generally dated between the beginning of the 7th century to the start of the 6th century BC.

Ostrich shells originated in Africa.

The alabaster jars probably came from Egypt. About fifty jars dating to the 7th century BC have been found in southern Spain and on the island of Ibiza.

The thymiateria may well have been manufactured on Cyprus, however, the number found on the Iberian Peninsula may indicate a more local origin, a metalworker copying a Cypriot design.

The ovoid transport amphorae probably came from Carthage. Their distribution pattern extends from Toscanos, a Phoenician port 38 kilometres east of Cerro de la Villar and, incidentally, the location of at least one large warehouse for storing products in transit, to Sant Marti d'Empuries in Catalonia, and Sa Caleta on the island of Ibiza. This pattern of amphorae appears in contexts relating to the 7th and 6th centuries BC, with peak production between 625 and 575 BC.

What was the purpose of the cargo?

Ordinarily, ivory was used to make high value ornaments, often inlaid with amber or metals, hair accessories, works of art, religious objects, ornamental hilts on daggers and knives, and boxes to name just a few uses. Six of the whole ivory tusks recovered from the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck appeared to be finished with inscriptions that would normally have been found in a sanctuary. The remainder were raw ivory that would have been destined for cutting, working, and polishing into high value goods.

The metallic raw materials were all in demand throughout the Mediterranean and would have been destined for smelters to be made into tools, weapons, pipes, containers, jewellery, and ornaments.

The amber had no other use at that time apart from ornamentation and jewellery.

Resin was used to flavour wine and as an adhesive.

Pitch was used to waterproof the hulls of ships. That found on board the wreck could have been part of the ship's stores.

The uses to which the ceramic collection was put is self-evident.

Ostrich shells were used by the Phoenicians in art and ritual, reviving a tradition dating back to the early bronze age. The shells made a luxury receptacle that was mounted on an ornate stand made from ivory or precious metal. They are common throughout southern and eastern Iberia valued by both Phoenicians and the native inhabitants. The cut and form of the eggshells found on the Bajo de la Compana wreck have only been found on Ibiza. The greatest concentration of more than 700 ostrich eggshell receptacles are found at the Phoenician necropolis at Baria near Villaricos.

Most of the alabaster jars found in Spain have been used in a funerary context, as cremation urns in elite burials. The necropolis at Baria for instance, contained a number of alabaster cremation urns.

Thymiateria are incense burners that were used in funerial rites and in domestic situations to produce an enticing aroma or mask foul odours.

The votive altar, like the inscribed ivory, would normally have been found in a sanctuary.

The balance weights are an essential and personal tool for the merchant trader and indicate that the trader was on board the ship when it sank. It is possible that this person was also the master of the ship.

Taken as individual items, the cargo is an eclectic mix. Some researchers

Hypothesis

The furniture parts only made up one item of furniture in each case, a chair, stool, or table in the case of the bronze legs, one couch judging from the number of corner pieces found and one bronze cauldron. This sounds more like a house removal than an assortment of furniture for indigenous trading partners. It also appears that the ship was travelling west to east, in other words on its return journey to the Levant, any trade goods originating in the Middle East would surely have been used on the outward journey.

If we then look at some of the rest of the cargo, the alabaster jars, the thymiateria, the decorated double-ended boxwood combs, carved ivory hilts for daggers and a small spool shaped ivory ring base, the blue glass base for a decorative stand to hold an ostrich shell, the tripod mortars or bowls, and the altar. All these items suggest a sanctuary context or possibly the home of an elite member of society.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that the cargo was in two parts.

The metallic raw materials, ivory, and amphorae that would have contained perishable products such as oil, wine, and salted fish, were destined for the eastern Mediterranean or the Middle East.

The second part of the cargo was personal items that belonged to an elite member of Phoenician society, possibly a rich merchant, relocating to a new base or even returning to his home city.

This author hypothesizes that the elite passenger was a guardian of a sanctuary and that he was on his way to establish a new sanctuary. At the end of the 7th century BC, most of the population at the Phoenician settlement of Cerro del Villar moved to nearby Malaka (Malaga), leaving a nucleus of specialists who produced amphorae in what had become an industrial complex, rather like a modern industrial estate on the outskirts of a town. Could a sanctuary priest from Cerro del Villar have considered moving the sanctuary to a more propitious location?

As to where this proposed new sanctuary would be located. A best guess would be Ibiza, that being a logical destination for the Bajo de la Campana ship (see below) and an island that was being actively developed by the Phoenicians during the 8th and 7th centuries BC.

Where did the Bajo de la Campana ship come from and where was it going?

During the 9th century BC, Phoenician traders travelled the length of the Mediterranean, east to west, went out into the Atlantic and established a colony at Gadir (Cadiz). This was a strategic move to leapfrog ahead of the competing Greek traders in the eastern Mediterranean and then work backwards, establishing colonies as they did so. Gadir was founded about 850 BC whilst colonies further east were founded later, Cerro de la Villar was founded in the second half of the 9th century BC, shortly after Gadiz, Carthage in 814 BC, Malaka (Malaga) was founded about 770 BC and La Fonteta about the same time. Sa Caleta was founded somewhat later, around 700 BC. The indigenous population of the Iberian Peninsula from southern France, southwest as far as Malaga were the newly emerging Iberians whilst the Tartessians inhabited the Guadalquivir valley and what is now the provinces of Cádiz and Huelva. The culture to which they gave their name developed during the 9th century BC as a direct result of Phoenician influences.

The cargo being carried by the Bajo de la Campana ship and the geographical location of its demise suggest that the ship was operating between the western Phoenician colonies within a triangle formed by Cerro de la Villar, La Fonteta and Sa Caleta on the island of Ibiza, and all ports in between.

The lynchpin in this triangle was Cerro de la Villar that had direct maritime trading connections with the mining areas of southwestern Andalucia through the entrepot ports of Gadir (Cadiz) and Onoba (Huelva), both on the Atlantic coast. They in turn connected to the silver and tin mining areas in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, in northern Portugal and Galicia through Phoenician established colonies on the coast of Portugal. Cerro de la Villar had all the characteristics of an early emporium.

Cerro de la Villar

Cerro de la Villar was situated at the mouth of the Guadalhorce river a few kilometres from the modern city of Malaga. The inhabitants of Cerro de la Villar lived in large dwellings built by the early part of the 7th century BC. The economy was based on agriculture, livestock, fishing, and fish products both locally sourced and via trading links with the indigenous Tartessians inland who were reached via the Guadalhorce river valley. The only downside to Cerro de la Villar was its size. With sea levels being a little higher than they are today, Cerro de la Villar would have been a small island.

Manufactured products included metalwork, textiles, purple dye from murex shells, and ceramics made from the extensive and excellent clay deposits nearby. The clay workings are still visible today and have been preserved as a bird sanctuary.

During the 7th century, Cerro de la Villar experienced tremendous economic growth due to increased trade with the Tartessians and its advantageous location that made it a major instigator in the Phoenician push to achieve trade dominance, and eventually a monopoly, along the eastern seaboard through to the far northeast of the Iberian Peninsula. Later, in the 7th century BC, the increase in trade necessitated a removal of the majority of the population from Cerro de la Villar to the city of Malaka just a few kilometres away, allowing Cerro de la Villar to become a purely industrial site with retail spaces, forges, metal workshops and pottery kilns.

La Fonteta

La Fonteta was founded at the mouth of the Segura river, about 45 kilometres north of the Bajo de la Campana wreck site. The colonists exploited the mineral resources of the Sierra de Crevillente that extends from Murcia, parallel to the coast, as far as Alicante.

The economy was based on metalworking, copper, bronze, silver, lead and later, iron. Nearby enclaves at the Iberian sites of Pena Negra and Saladares produced ceramics and eastern Mediterranean style jewellery.

Excavations at La Fonteta have recovered virtually every type and style of pottery that was found on the Bajo de la Campana wreck, in addition to locally produced ceramics, demonstrating an active trading link with Cerro de la Villar and other workshops along the Malaga coast.

Ceramics were not the only products to show a trading link between the two ports. Analysis of both metallic and mineral lead discovered at La Fonteta, indicated that La Fonteta was importing galena that had the same origins as the galena found on the Bajo de la Campana wreck.

Sa Caleta

Sa Caleta was a Phoenician colony established in the early 7th century BC, on the southern end of the island of Ibiza, about two hundred kilometres northeast of La Fonteta. The colony lasted about one hundred years and then relocated to another site on the northeast side of the Bay of Ibiza.

During its brief existence, Sa Caleta was supplied with the majority of its wheel made pottery from workshops in southern Andalucia. The Bajo de la Campana wreck contained transport amphorae, tripod mortars, plates, and bowls, carinated bowls, lamps with two nozzles, oil bottles, and several types of jugs identical to others found at Sa Caleta.

The local economy was based on milled grain and livestock, salt, fishing and the harvesting of molluscs, weaving, and metallurgy. Locally mined iron ore was processed at Sa Caleta whilst other foundries produced lead and silver and recycled scrap copper and bronze to produce various bronze utensils.

Analysis of galena found at Sa Caleta showed that it originated in the Sierra de Cartagena in Murcia. The imported galena was mixed with a local ore found in the north of the island and the substantial stockpiles of the ore suggested that the colony was exporting metallic lead.

The Last Voyage of the Bajo de la Campana ship

The items recovered from the shipwreck indicate that the Bajo de la Campana ship, on its last voyage at least, operated solely in the western Mediterranean at the end of the 7th or beginning of the 6th century BC when the Phoenicians were most active in the area.

The voyage probably started at Cerro de la Villar. Many of the items recovered from the wreck would have been available at this key trading site having arrived as cargo on other trading craft. For instance, the inscribed ivory from a sanctuary somewhere on the peninsular, possibly Cadiz, accompanied by our hypothetical peripatetic priest. The tin came from the Galicia region that had arrived at Cerro de la Villar either by sea down the Atlantic coast and through the Strait of Gibraltar, or, less likely, overland. The copper originated in the western part of Andalucia and would have been transported south to Huelva or Cádiz and may well have arrived at Cerro de la Villar on the same ship that carried the tin. It is even possible that our hypothetical peripatetic priest travelled on the same ship with the tin and copper.

The copper from more distant regions in the central Mediterranean, the Baltic amber, the ceramic vessels that originated in the Middle East, the luxury goods, if not part of a priests� personal effects, likewise from the Middle East, would have arrived at Cerro de la Villar via numerous hands and ships, each employed on fairly local trading routes that together knitted the Phoenician maritime trading network together.

The Bajo de la Campana ship loaded a cargo of locally manufactured urns and amphorae. Whatever perishable products, olive oil, wine, fish products etc., were being carried in the transport amphorae probably had a local source.

Having loaded its cargo at Cerro de la Villar, the ship sailed east to Toscanos where it picked up the Carthaginian ovoid amphorae and the elephant ivory from North Africa, probably also from Carthage. From there it sailed east to Abdera to acquire a load of galena, perhaps calling in at Sexi (Almunecar) on the way.

The ship continued its journey east and rounded the Cabo de Gata to now head northeast past Baria (Villaricos) and Punta de los Gavilanes (Mazarron) and may well have called off at both places before reaching Cape Palos, just south of the Mar Menor. Here the route heads north to pass the Mar Menor, and onwards to La Fonteta at the mouth of the Segura river.

Unfortunately, the ship came to an untimely end on the Bajo de la Campana shoal before reaching La Fonteta.

Had the ship reached La Fonteta, it may well have unloaded some of its cargo judging by the discovery of similar or identical artifacts at La Fonteta, such as the galena and the Andalucian pottery. La Fonteta may also have been the intended destination of some or all of the luxury goods that could have been used as exchange commodities or gifts with the indigenous Iberian elite. No doubt the ship would have then loaded locally produced products.

The ship's cargo, or part of it, could easily have been destined for Sa Caleta judging from the excavated evidence from the region, in particular, the ovoid Carthaginian amphorae. The return cargo would have been the products produced at or in the enviros of Sa Caleta.

Such a triangular journey, with intermediate stopovers, is attested to by the artifacts found at each of the destinations on the route.

Why did the Bajo de la Campana ship sink?

It is likely that, on rounding Cape Palos, the ship encountered a strong easterly wind locally called a Levanter. This would have made the whole of the Mar Menor coast a lee shore. The ship could easily have been driven towards the shore and was then unable to avoid the Bajo shoal.

Ongoing Research

The last voyage of the Bajo de la Campana, based on the recovered cargo and the artifacts discovered at the most likely ports, is a fascinating story that leads to more questions. Why was lead and galena being transported in two directions? What goods would have been received for the ship's cargo at each stage to make a triangular voyage profitable? Was the Bajo de la Campana ship engaged on a perpetual triangular voyage, or was its last voyage only part of a longer journey? Where were the bronze goods manufactured? How does the last voyage of the Bajo de la Campana ship fit in with the overall narrative of Phoenician trading activity in the Mediterranean Sea?

Where is the Bajo de la Campana cargo now?

Some of the cargo from the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck can be viewed at the Museo Nacional de Arqueologia Subacuatica. Cartagena.

References

Museo Nacional de Arqueologia Subacuatica

Polzer, Mark. (2014). The Bajo de la Campana Shipwreck and Colonial Trade in Phoenician Spain.

Rey, Beatriz & Meunier, Emmanuelle & Figueiredo, Elin & Lackinger, Aaron & Fonte, Jolo & Fernandez, Cristina & Lima, A. & Mirao, Jose & Silva, R.J.C. (2017). North-West Iberia tin mining from Bronze Age to modern times: an overview.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC 2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC

2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC 3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC

3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC 4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC

4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC 5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC

5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC 6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC

6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC 7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC

7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC 8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period

8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period 9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period

9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period 11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC

11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC 12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC

12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC 13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC

13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC 14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC

14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC 15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC

15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC 16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC

16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC