Civilisations that Collapsed

The Strangulation of Bronze Age Trading Networks

To what extent were trade routes disrupted during the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East and what contribution did that disruption make to the collapse? We look at the ‘Slow Strangulation’ of the Bronze Age Trading Networks in the Middle East.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-12-8 | Last Updated 2025-12-9 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 1,741 times

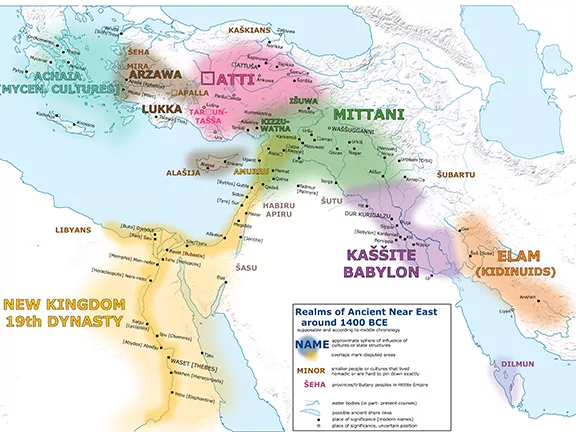

Bronze Age Middle East Trading Networks c 1250 BC. Map by Julie Evans

Trade Routes Maketh the Empire

We have seen that developing trade routes by sea and land was essential during the formative years of emerging empires in the Middle East. Without the trade routes and the wealth of goods that moved along them, the Palace-Temple economies in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean would not have developed, and the Empires would not have existed, at least not in the form they took during the Bronze Age.

However, the question remains whether a disruption of these routes was a sudden, catastrophic event that toppled empires overnight, or a more insidious process. This article proposes a hypothesis of "Death by Strangulation." Rather than a massive, fatal heart attack triggered by invaders in the years around 1177 BC, the evidence suggests the empires were slowly suffocated over decades. The disruption of key trade arteries, starting as early as 1250 BC, starved the Great Powers of the resources and legitimacy they needed to survive, rendering them too weak to withstand the final shocks of invasion or internal revolt.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The High Stakes of Interdependence

To understand how trade disruption could topple an empire, one must first recognise that the Bronze Age Middle East operated within certain constraints. The dispersed source of essential materials forced independent states into a web of dependency that made them vulnerable. There are three strands to this dependency: tin and copper (strategic necessities); grain, oils and wine (subsistence interdependence); and prestige goods (elite legitimacy).

Strategic Necessities: Tin and Copper

The primary vulnerability lay in the material that defined the age. Bronze is an alloy, requiring copper and tin. While copper was relatively accessible (primarily sourced from Cyprus, the "Copper Island"), tin was the era’s "strategic oil"—rare, essential, and distantly sourced. The main sources of tin lay thousands of miles to the east, in the mines of Badakhshan (modern Afghanistan).

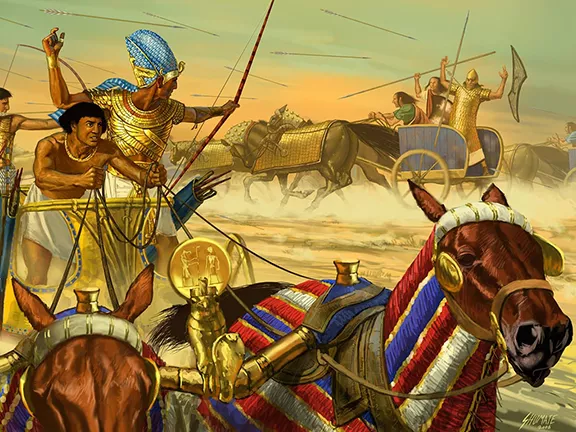

This created a "distance parity." No single Great Power, whether the Egyptians, Hittites, Assyrians, Elamites, or Mycenaeans, controlled all the resources needed to equip their armies. To forge a sword in Mycenae, a shield in Assur, or a ploughshare in Hattusa required a supply chain that spanned the known world. Therefore, trade in tin and copper served not as a luxury, but as a matter of national security, much like oil is in the modern world.

Subsistence Interdependence: Grain, Oils and Wine

The trade networks also carried the calories that sustained the urban populations. The Hittite Empire in Anatolia, often plagued by arid conditions and frequent crop failures, became dependent on massive grain shipments from Egypt and the Canaanite coast.

The correspondence of the era reveals the desperation of this reliance. About 1213 BC, Hittite Queen Puduhepa wrote to Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II: "I have no grains in my lands." Later, Pharaoh Merneptah (1213-1203 BC) recorded that he "caused grain to be taken in ships, to keep alive this land of Hatti," an early instance of international famine relief.

Another urgent message from the Hittite court to the Ugaritic king (either Niqmaddu III or Ammurapi) demanded a ship and crew for the transport of 2,000 kor (circa 450 tonnes) of grain from Mukish to Ura, emphasising: "You must not detain their ship!"

A remarkable letter from the king of Tyre to the king of Ugarit illustrates the cooperation between city-states, even amidst crises. It describes a grain ship from Egypt, intended for Ugarit, caught in a storm off Tyre. The king of Tyre salvaged the grain and crew, returning them to Ugarit's care: "Your ship that you sent to Egypt died in a mighty storm close to Tyre. It was recovered and the salvage master took all the grain from the jars. But I have taken all their grain, all their people (crew), and all their belongings from the salvage master and have returned it all to them. And now your ship is being taken care of in Akko, stripped."

Even the wealthy merchant city of Ugarit itself was not immune.

Pharaoh Merneptah's reply to the king of Ugarit, sometime between 1213 and 1203 BC, confirms: "So you had written to me... in the land of Ugarit there is severe hunger. May my lord save the land of Ugarit and may the king give grain to save my life and to save the citizens of the land of Ugarit."

Ugaritic merchant Rapanu wrote: "The gates of the house are sealed. Since there is famine in your house, we will starve to death. If you do not hasten to come we will starve to death. A living soul of your country you will no longer see."

Towards the city's final days, an unnamed king of Ugarit lamented: "with me, plenty has become famine," and an Ugaritic official pleaded with the king: "Another thing my lord, grain staples from you are not to be had. The people of the household of your servant will die of hunger. Give grain staples to your servant."

By way of contrast, the Mycenaeans and Minoans industrialised the production of olive oil and wine, exporting these staples in standardised amphorae to pay for the raw materials they lacked.

This "Subsistence Interdependence" meant that the trade routes functioned as famine relief lifelines. A blockage in the grain supply could turn a recession into a famine.

Elite Legitimacy: Prestige Goods

While tin, copper and grain were necessities, it was the flow of prestige goods—gold, silver, exotic spices, and purple-dyed textiles—that lubricated the political machinery. These items were not just decorative; they functioned as the currency of power. The elite class defined its existence through the consumption and display of foreign wealth. Possession of Nubian gold or Baltic amber was seen as physical proof of a ruler's international reach, enhancing his reputation and bolstering his legitimacy.

The stability of the Middle East relied on the "Brotherhood of Kings," a diplomatic network where stability was maintained through the exchange of gifts.

The Amarna Letters (1360–1332 BC) reveal Great Kings pleading for gold "for gold is as dust in your land" to maintain their status. Without these expensive offerings, a King's ability to buy the loyalty of local warlords evaporated, making the empire susceptible to internal coups and fragmentation, an open invitation to a foreign invader. The letters, 382 in total, reveal the extent of the trading networks at that time.

The Pharaohs Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, corresponded with the ‘Great Powers’, Babylonia, Assyria, Mitanni, and Hatti. They also communicated with the wannabe great powers, Arzawa (a kingdom in western Anatolia) and Alashiya (Cyprus). In addition, through the Amarna letters, we learn of the networks for gold and exotic goods from Egypt to the vassal city-states, Byblos, Jerusalem, Megiddo, Shechem, Gezer, Ashkelon, Gaza, Tyre, Sidon, Amurru and Ugarit, that ‘Switzerland’ of the Bronze Age, a wealthy merchant state that wanted to trade with everyone and fight no one that found itself in the Egyptian sphere of influence during the early 13th century BC.

The Palace-Temple economies had evolved into "Just-in-Time" delivery systems, lacking the resilience to withstand prolonged disruption.

The Anatomy of the Network

By 1250 BC, the region relied on a constellation of "Gateway Cities" that managed specific sectors of this international supply chain.

The Tin Road (The Eastern Gateways)

Tin from Afghanistan entered the Middle East along two roads, a southern route and a northern route. The latter was well established, having been in use since before 1920 BC when it was operated by the Assyrian merchants from their karum at Kanesh. However, it was the southern route that brought the bulk of the tin to feed the empires during the Bronze Age.

The Southern Route

The first leg, from Badakhshan across the Iranian plateaux was controlled by the Elamites, based in Susa (modern Iran), and the tribal confederations of the Zagros Mountains such as the Gutians and Lullubi. They each extracted a ‘toll’ on goods passing through their territory.

The tin arrived in Susa via the southern passes through the Zagros mountains. From there it was transported to Babylon and then up the Euphrates river to Emar. The Kassite Babylonians controlled this leg of the journey. The "Diviner's Archive" at Emar reveals that this trade was managed not just by the King, but by powerful private merchant firms, such as the "House of Zu-Ba'la", who operated independently of the palace. Emar was the crucial "dry port" where river boats offloaded tin onto donkey caravans to carry the metal across to Ugarit.

This route was vulnerable to the nomadic Sutean and Ahlamu (early Aramean) tribes who raided caravans, eventually severing the link as central authority faded.

If Elam was hostile towards Babylon, as it often was, the southern route was blocked, forcing trade north towards Assyria.

The Northern Route

Controlled by Assyria, whose merchants (karum) had historically dominated trade into Anatolia, this is the route that kept Assyria alive at the end of the Bronze Age.

From Afghanistan, the tin was carried in donkey caravans through the northern Zagros mountain passes to Assur and Nineveh. From there it continued across the plains of Northern Mesopotamia, via the bottleneck of Emar, into Anatolia.

By the Late Bronze Age, Assyria enforced a protection racket on these caravans, effectively holding a veto over whether the Hittites and Mycenaeans received their metal.

The Copper Hub (The Cypriot Gateways)

Cyprus (Alashiya) supplied the copper in the form of the ubiquitous ox hide ingots, operating through three regional gateways:

Enkomi (East Coast): The "Eastern Gateway," facing Syria. Enkomi was the principal trading partner for Ugarit and the Hittites, serving as the heavy industrial hub for the northern empires.

A modern analogy would be Dover, in England, on the northern side of the English Channel and Calais, in France, on the southern side of the English Channel. A steady stream of freighters and passenger ferries between the two move huge volumes of cargo and humans between the two countries on a daily basis. Any disruption on one side has an immediate impact on the other. Not surprisingly the two Port Authorities are in constant communication to keep traffic moving smoothly.

Kition (Southeast Coast): Kition was the "Southern Gateway," positioned to serve Egypt and the Southern Levant.

Palaepaphos (West Coast): Palaepaphos was the "Western Gateway," the point of departure for ships heading to Crete (Kommos) and the Aegean.

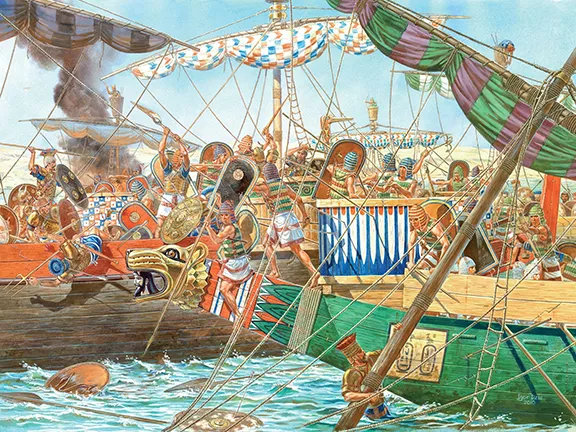

The Maritime Pivot (The Levantine Gateways)

Ugarit: The supreme entrepôt. Unlike the vast territorial empires of the Hittites or Egyptians, Ugarit was a merchant city-state. It produced little of its own but facilitated the movement of everything. It was the pivot point where overland caravans from Mesopotamia met the maritime fleets of the Aegean and Cyprus. The city’s Tamkaru (Royal Merchants) functioned as a cartel, effectively monopolising the interface between the tin caravans and the Mycenaean ships.

Byblos: The veteran supplier of cedar and the primary diplomatic interface with Egypt.

Hazor: The dominant fortress-city controlling the Via Maris, the essential overland artery connecting Egypt to the North. For centuries, Egyptian gold and grain travelled north along the heavily fortified military road known as the "Ways of Horus," which terminated at the port of Gaza. From there, the route transitioned into the "Via Maris", the international highway that ran 175 km north to Hazor.

Long before the destruction of the city, written evidence implies that the people and leaders of Hazor were rebels.

Although written about 100 years before the destruction (c. 1350 BC), the Amarna letters provide a profile of the city that supports the idea of independence and unrest.

In the Amarna diplomatic correspondence, the ruler of Hazor (Abdi-Tirshi) is the only Canaanite vassal ruler who dares to call himself "King" (Sharru) rather than just "Mayor" or "Governor" when writing to the Pharaoh.

Other city-states (like Tyre and Ashtaroth) wrote to the Pharaoh complaining that the King of Hazor had rogue tendencies, accusing him of aligning with the ‘Apiru (stateless bandits and mercenaries) to seize territory.

The Egyptian letter,Papyrus Anastasi I, dates to the reign of Ramesses II (mid-13th century BC), very close to the time of Hazor’s destruction.

It describes the geography of Canaan and mentions the "stream of the Qir" near Hazor.

While it describes the dangers of travel (bandits, difficult roads), it treats Hazor as a known landmark. The fact that it doesn't mention a massive Egyptian military campaign there in the late 13th century is sometimes used to argue against an Egyptian destruction (like that of Seti I or Ramses II), indirectly leaving the alternative, internal collapse or local warfare. Flimsy, negative evidence, but the idea has been mooted.

The Manufacturers (The Aegean Consumers)

At the end of the line were the Mycenaeans. While the Middle Eastern powers controlled the raw resources, the Mycenaean civilisation of mainland Greece functioned as the industrial manufacturing hub on the northwestern end of the network. Their palaces were not just royal courts, but factories that processed raw imports into high value exports, creating a "Value Added" economy that balanced their trade deficit with the East. The Mycenaeans were the manufacturers of value-added products par excellence.

To pay for the copper and tin they required, the Mycenaeans built a substantial export industry focused on high value manufactured goods. Their principal exports included perfumed oils, luxurious textiles, and, most notably, fine pottery. Mycenaean ceramics, in particular, became highly sought after throughout the eastern Mediterranean.

The Mechanics of Failure: Leading Theories

To understand the collapse, we must look at the theoretical frameworks that underpin the "Strangulation" hypothesis.

Systems Collapse (Eric Cline)

In his seminal work “1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed”, Eric Cline argues for a "Systems Collapse." Cline posits that the civilisations were "hyper-coherent"—so tightly interconnected that they became brittle. Cline uses the metaphor of a "perfect storm" of stressors (earthquakes, drought, migration) hitting the system simultaneously. In this model, the blockage of a single route transmits shockwaves through the entire network.

Subversion from Below (Susan & Andrew Sherratt)

They argue that the collapse was driven by decentralisation. A rising class of independent merchants bypassed the royal palaces, "strangling" the Palace economies by cutting off their monopoly on wealth.

Climate Forcing (David Kaniewski)

Pollen analysis indicates a severe, centuries-long drought (the "3.2 ka event") from about 1200 BC to about 1000 BC. This suggests the agricultural surplus used to buy foreign goods was dwindling long before the cities burned.

The Chronological Anchor (Israel Finkelstein)

Finkelstein’s radiocarbon dating pushes the destruction of the inland fortress of Hazor back to about 1250 BC, nearly 70 years before the coastal collapse. The 'coast' in this context refers to the great maritime emporiums stretching from Ugarit in the north to the Philistine cities of Ashkelon and Gaza in the south, which archaeological and textual records confirm were destroyed during the chaotic 'Sea Peoples' invasions of about 1185 to 1177 BC.

The "smoking gun" for this early date lies in the ashes of the Upper City of Hazor, the Acropolis (the high mound or Tell) where the Ceremonial Palace, the administrative archives, and the main temples were located. This was the seat of the King and the elite. The destruction layer contains Mycenaean IIIB pottery (mid-13th century) but completely lacks the Mycenaean IIIC style associated with the 1200 BC collapse.

This significant time lag is the linchpin of the Strangulation hypothesis: the interior "valve" broke three generations before the coast died.

The Physical Evidence of Scarcity

The "Strangulation" hypothesis is not merely a theoretical timeline; it is supported by physical evidence of a world slowly running out of resources.

The Scrap Metal Economy: Wealth vs. Waste

The shift from abundance to strangulation is visible in the archaeology of shipwrecks. The Uluburun ship that sank off the southern coast of Anatolia about 1300 BC, carried tonnes of "virgin" raw copper and tin ingots. By way of contrast, the Cape Gelidonya ship that sank nearby in about 1200 BC, dating to the end of the era, carried almost no raw ingots but rather scrap bronze, broken tools and ploughshares collected to be melted down. The merchants were no longer transporting new wealth; they were scavenging the debris of a dying economy.

This desperation is mirrored in the Pylos Linear B tablets (c. 1180 BC). Pylos was a major Mycenaean centre in Messenia, on the southwest coast of Greece's Peloponnese. Just months before the Palace of Nestor was burned, priests recorded a frantic collection of "temple bronze" to be melted down for weapons. The state was cannibalising its own gods to survive.

The Death of Credit: The Rise of Hacksilber

The strangulation also killed the "trust" required for international credit. During the height of the Bronze Age, trade was often done via royal gift exchange. However, as the palaces began to fail, we see a massive spike in "Hacksilber" hoards in the Levant (e.g., at Tel Dor and Megiddo). Hacksilber consists of silver jewellery chopped into small, irregular pieces to be weighed on a scale. This signals a shift to a "cash-only" economy; merchants no longer trusted the King's promise and demanded raw bullion on the spot.

The Calorific Strangulation: The Grain Crisis

While the elite worried about gold, the population worried about bread. The Hittite Empire in Anatolia relied on grain shipments from Egypt and Ugarit to survive. As the trade networks tightened, this caloric lifeline frayed.

A letter from the Hittite king to the king of Ugarit just prior to the collapse urgently inquired about a shipment of two thousand units of grain (up to 450 tons) from Ugarit to Hattusa, ending dramatically: "It is a matter of life or death."

The Fiscal Crisis: The First Strikes

Finally, we have proof that the strangulation bankrupted at least one state, Egypt. Deir el-Medina is on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Luxor. There, workers built a complete artisan village, including homes for workers, their elaborate, beautifully decorated tombs with small pyramids, and temples most famously the Ptolemaic Temple of Hathor, all serving the New Kingdom craftspeople who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. In the aftermath of the collapse (c. 1150s BC), the artisans at Deir el-Medina launched the first recorded labour strike in history because the Pharaoh could no longer provide their rations. Even the richest man on earth could not pay his bills.

The record of the strike is found in the Turin Strike Papyrus, written by the scribe Amennakhte during the 29th year of the reign of Ramesses III (c. 1157 BC). The papyrus provides a detailed, day by day account of the events when the artisans of Deir el-Medina. The workers downed tools and marched on the mortuary temples because their grain rations had not been delivered for weeks. It records their famous chant, "We are hungry! ... We have no clothing, no ointment, no fish, no vegetables!"

A Critical Reassessment: Disruption or Transformation?

Archaeologist Jesse Millek’s forensic audit of 148 sites reveals that the collapse was not simultaneous. By applying radiocarbon dating and re-examining excavation reports, Millek demonstrates that the "simultaneous" collapse was actually a staggered series of unconnected events.

Hazor (The "Time-Travel" Error)

As noted, Hazor was destroyed about 1250 BC, decades before the Sea Peoples arrived. It was the precursor to the collapse of the trading networks, not the result.

Cypriot Survival: Destruction and Transformation

The fate of Cyprus illustrates a violent struggle for survival. Excavations by Porphyrios Dikaios at Enkomi identified a destruction layer (Level IIB) marked by ash dated to about 1200 BC. However, unlike Ugarit, Enkomi was not abandoned. It was immediately rebuilt with massive Cyclopean walls, converting the open trading hub into a militarised bastion.

This pattern of "contraction and fortification" is mirrored across the island, confirming a systemic breakdown of security. Vassos Karageorghis identified a "crisis horizon" about 1200 BC where peripheral defensive sites failed. The inland fort of Sinda was destroyed by fire, the short-lived defensive outpost at Pyla-Kokkinokremos was suddenly abandoned, its population fleeing so quickly they buried their silver hoards in the ground, and the fortified headland of Maa-Palaeokastro was destroyed shortly after its construction.

These failures indicate that the "Strangulation" eventually overwhelmed the island's outer defences, forcing the population and resources to retreat into the surviving fortified centres like Enkomi, Kition, and Palaepaphos. These hubs survived the initial shock, maintaining a "silver thread" of trade with the Levant well into the Iron Age, until environmental factors, like the silting of Enkomi’s harbour about 1050 BC, finally completed what violence could not.

Byblos (The Recession)

There is no destruction layer at Byblos. The city merely suffered from economic atrophy. Millek points out that "twelve non-local types of material culture" persisted across the transition in the Southern Levant, suggesting that the "collapse" was actually a gradual transition into the Iron Age economy.

Ugarit (The Exception)

Ugarit is the only major hub to suffer terminal destruction about 1185 BC.

Ugarit was not treated like a standard vassal. The Hittites realised that Ugarit was more valuable as a bank than as a barracks. While other Hittite vassals (like Amurru) were required to send troops to fight in Hittite wars (such as the Battle of Kadesh 1287 BC), Ugarit was often allowed to pay "Blood Money" in the form of gold instead of sending soldiers.

The tribute imposed on Ugarit was staggering. Texts record massive payments of gold, dyed purple wool, and textiles sent to Hattusa. The Hittites effectively "farmed" Ugarit for its wealth. They protected the city so it could generate the revenue needed to fund the Hittite military machine.

However, as a Hittite vassal, Ugarit was forced to send its grain and ships to feed the starving Hittite homeland, leaving the port defenceless. The famous "Oven Letter", found in a kiln where it was being baked but never sent, speaks to the suddenness of the end: "My father, behold, the enemy's ships came... my cities were burned... Thus, the country is abandoned to itself."

The Strangulation Hypothesis: A Chronology of Decline

Synthesising the theories of Cline and Finkelstein with Millek’s forensic dating, we can construct the "Death by Strangulation" timeline. The trade routes were not cut in a day or even a year, they were slowly choked off through a combination of internal warfare, politically inspired embargoes, and military action, creating a scarcity of resources that corroded the empires from the inside.

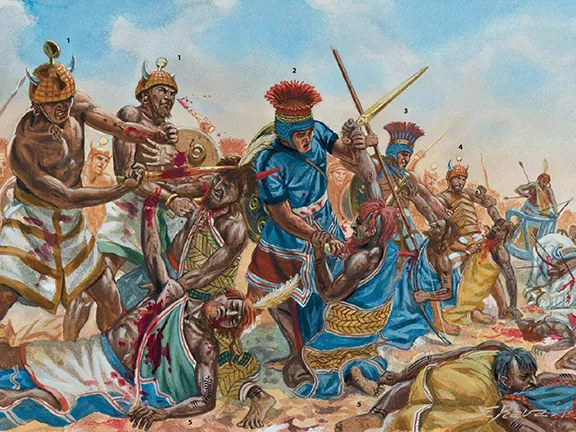

The Severing of the South: The Hazor Valve (c. 1250 BC)

The strangulation began when Hazor was destroyed. This effectively shut the "valve" of the Via Maris.

The destruction of the Ceremonial Palace in the Upper City was not merely a fire; it was an inferno. Archaeologists found a layer of ash over a metre thick. The heat was so intense, estimated at over 1,300°C, that the mudbricks of the palace walls did not just crumble, they vitrified (turned to glass) and melted into slag. This level of heat requires a massive, deliberate fuel source, probably stored olive oil jars used as accelerants. This indicates that the destruction was a calculated act of annihilation aimed at the seat of power, not an accidental fire or a raid conducted by enemy forces.

The destruction also appeared to be ideological. In the palace ruins, excavators found Egyptian and Canaanite statues that had been systematically mutilated. The heads and hands of the deities and royal figures were chopped off before the fire was set. This iconoclasm suggests the attackers were not foreign looters, who would have stolen the statues for their value, but locals expressing a violent rejection of the ruling elite and their gods. This supports the theory of an internal uprising triggered by economic hardship.

Furthermore, archaeologist Sharon Zuckerman noted a discrepancy between the Upper and Lower cities. While the Upper City, the acropolis of the King and priests, was obliterated, parts of the Lower City, the residential district of the commoners, showed signs of abandonment rather than total destruction. This pattern is consistent with a "Peasant's Revolt", the population turning on a palace that could no longer feed them, burning the administration while leaving their own homes intact.

This blockage placed a tourniquet on the flow of southern wealth to the north. Consequently, the intermediate port of Byblos began its "economic atrophy," fading into irrelevance not because it was attacked, but because the road it served was closed.

The Political Chokehold: The Hittite Embargo (c. 1225 BC)

With the southern route chaotic, the central route was deliberately strangled by imperial policy. For centuries, the Hittites viewed the Mycenaeans (Ahhiyawa) as a geopolitical threat.

Around 1225 BC, this friction evolved into active economic warfare. The Hittite King Tudhaliya IV, threatened by the rising power of Assyria, signed a treaty with his vassal Shaushgamuwa, King of Amurru, the coastal region of modern Syria and Lebanon.

The treaty explicitly weaponised the trade routes, ordering Amurru to enforce a strict blockade: "No ship of Ahhiyawa may go to him [the King of Assyria]..." This embargo effectively slammed the door on Mycenaean access to the lucrative inland markets of the Near East via the Levant. With the southern route, via Hazor, blocked by war and the central route, via Amurru, blocked by law, the Mycenaeans were being systematically squeezed out of the international economy.

The Cretan Retreat: A Flight from the Coast (1200 – 1190 BC)

The collapse of the Mycenaean trading centres on Crete provides a distinct counter-narrative to the mainland. While Mycenae was destroyed from within, Crete was terrorised from the sea.

Kommos: The southern gateway to Egypt was abandoned without a fight about 1200 BC. As the "Hazor valve" cut the flow of Egyptian goods, Kommos became a port without a purpose.

Cydonia (Chania): The island's main Mycenaean administrative hub was destroyed by fire about 1190 BC.

The Refuge Phenomenon: Most tellingly, the survivors did not rebuild, as at Enkomi, or revolt, as at Mycenae, they fled. The population abandoned the fertile coastal plains for "Refuge Sites" like Karphi, located on inaccessible mountain peaks. This indicates that following the economic strangulation, the unpoliced seas surrounding the island became a zone of such danger that the islanders chose isolation over commerce. There are many examples throughout history of people choosing to live in mountain redoubts close to the coast. In Andalucia, Spain, the famous white villages of Casares and Gaucin, allowed the occupants access to the agricultural lands and the coast whilst deterring the Barbary Pirates who were prone to periodic raids.

The Anatolian Exit: Miletus and Rhodes (c 1190 BC)

Miletus: Miletus was the primary Mycenaean foothold on the Anatolian mainland. It was the "forward operating base" for Mycenaean trade and military interference in Hittite affairs. The embargo imposed by the Hittite King Tudhaliya IV’s embargo about 1225 BC was specifically aimed at Miletus. The Hittites were trying to squeeze this city to stop Mycenaean access to the interior.

The city was violently destroyed about 1190 BC. The destruction layer is massive. While often attributed to the "Sea Peoples," it is equally likely this was the final Hittite crackdown or a result of the collapse of the hinterland trade routes.

Unlike Ugarit, Miletus was reoccupied, but the character changed. The rebuilding shows a mix of Mycenaean and local Anatolian culture, often associated with the "Sea Peoples" phenomenon. It ceased to be a trade hub for a Palace economy and became a pirate haven or a local strongpoint.

Rhodes: In contrast, the island of Rhodes survived. Much like Cyprus and Athens, it became a refuge for those fleeing the burning palaces of the mainland. In the 12th century BC, Rhodes flourished, serving as a critical waypoint that kept the "silver thread" of trade alive between the Aegean survivors and the markets of the Levant. Excavations at the cemetery of Ialysos show a wealth of "Late Helladic IIIC" pottery.

The Choking of the East (c. 1200 - 1187 BC)

Simultaneously, the eastern frontier collapsed.

A letter found in the House of Urtenu in Ugarit refers to a famine raging in the inland trade hub of Emar just before its destruction about 1187 BC: "There is a famine in your house; we will all die of hunger... You will not see a living soul from your land."

The famine weakened Emar and may well have encouraged the Aramean tribes to make their move. Pressure from the tribes severed the Euphrates route, culminating in the destruction of Emar about 1187 BC. This cut the southern route pipeline for tin from Afghanistan.

The Trojan Gamble: The Closed Back Door (c. 1180 BC)

With the eastern supply lines through Ugarit and Emar strangled, the Mycenaeans appear to have launched a final, desperate gamble to secure an alternative route to secure essential resources. Troy (Hittite Wilusa) controlled the Dardanelles, the strategic gateway to the Black Sea and its untapped metal reserves.

While the violent destruction of Troy VIIa occurred around 1180 BC, contemporaneous with the final collapse of the Mycenaean palaces, this was probably not a war of conquest, but a "Trade War" for survival. As noted by Trevor Bryce, this conflict was not a singular event but the culmination of over a century of friction between the Hittites and Mycenae (Ahhiyawa). This animosity can be traced back to about 1295 BC and the exploits of the Hittite renegade Piyamaradu, who destabilized the region with Mycenaean backing.

This implies that the northern trade route had been contested and unstable for generations. When the southern routes finally failed about 1200 BC, the Mycenaeans made a final, forceful attempt to seize this "back door" to the metal markets. However, while they succeeded in burning Troy, the effort failed to secure a stable lifeline. The destruction of Troy merely sealed the final exit, leaving the Mycenaeans trapped in a resource starved Aegean with no remaining options.

The Mycenaean Implosion: Civil War (c. 1190 BC)

The loss of gold from the South and tin from the East, hit the Mycenaeans hardest. As the "Value-Added" economy collapsed, the political unity of the Aegean disintegrated. The archaeological evidence suggests that the final blow came not from foreign "Sea Peoples," but from internecine warfare and social collapse triggered by resource desperation.

The Northern Threat (Thebes vs. Mycenae): The unfinished Cyclopean Wall across the Isthmus of Corinth provides the clearest evidence of the geopolitical fracture. The wall faces North, indicating that the Kings of Mycenae and Tiryns were not afraid of ships from the sea, but of an army marching from central Greece, in all probability, their old rival, Thebes.

Pottery sherds found within the fill of the wall date to the Late Helladic IIIB period (c. 1250–1200 BC). In other words, the wall was started in anticipation of an attack, at the same time or slightly after the razing of Hazor. The build was interrupted, large piles of stones were found gathered near the wall line, ready to be placed but never used, suggesting that the "Strangulation" or the invasion moved faster than the engineers could build. The threat they anticipated arrived before the defensive wall was ready.

The Pylos "Coast-Watchers" (Linear B Evidence): Just months before Pylos was burned (c. 1180 BC), the scribes recorded desperate administrative moves. They detailed the deployment of "watchers" (o-ka) to guard the coastlines, but more importantly, they recorded a frantic collection of "temple bronze" to be melted down for weapons, as detailed above.

The Breach at Corinth: The destruction of the harbour settlement of Korakou (Corinth) about 1190 BC suggests that this northern enemy successfully breached the Isthmus defences. This severed the land link to the Peloponnese, isolating the southern palaces.

Mycenae (Sacked): Consequently, the destruction of Mycenae may have been a two-stage event: a military defeat by rival Greeks followed by the looting of the city. The selective burning of the Granary and Archives implies that whether the attackers were Theban rivals or a starving local population, their target was the administration that hoarded the dwindling supplies.

Tiryns (Survived): The fate of Tiryns supports this "Greek vs. Greek" narrative. While the Palace, the seat of the royal dynasty, was burned, the Lower Town survived and expanded. This suggests a change in regime or a breakdown of central authority, rather than a genocidal wiping out of the population by foreign invaders.

Following the destruction of its palace, Tiryns made a remarkable recovery. In the period 1200 to 1050 BC, the city became one of the most important sites in the Peloponnese. Its political restoration and architectural expansion are unprecedented in other regions of Greece. An important harbour before 1200 BC, Tiryns soon re-established its position. Long-term excavations at Tiryns have provided evidence for relations with Crete, the Levant, Cyprus and Italy during the 13th and 12th cents BC. In 2019, a study of DNA from pigs revealed a further connection with Italy, a possible precursor to the greater expansion of Greek trading during the Iron Age, usually dated to after 800 BC.

Athens (Survived): Despite the chaos of civil war, Athens survived because it was geographically isolated from the main north to south invasion route. The city occupies a peninsula a few kilometres to the east of this route. It watched the giants of Thebes and Mycenae destroy each other, effectively "bypassed" by the conflict. Some historians are of the opinion that Athens became a refugee camp for people fleeing the Theban hoards. This theory is actually supported by an ancient Greek myth, “Return of the Heracleidae”.

The Athenians were prepared to defend their city. They built a Cyclopean Wall around the Acropolis and dug the Enneakrounos, a secret underground fountain house, to withstand a siege. Unlike the unfinished Isthmus wall, the Athenian defences were completed and held.

Analysis of pottery unearthed in Athens, shows that while other regions stopped producing, Athens continued into the LH IIIC phase without a break. This continuity suggests that Athens became a centre of stability and the new pottery styles were inspired by the refugees that took shelter in Athens.

Lefkandi (Survived): Just to the north of Athens, off the north coast, is the island of Euboea and the coastal town of Lefkandi. As with Athens, Lefkandi seems to have been on the periphery of the invasion from the north and survived largely intact.

Late Arrival of the Sea Peoples (c. 1177 BC)

By the time the Sea Peoples arrived to ravage the Levantine coast, the "global" economy was already dead. The invaders were not killing the empires; they were merely scavenging the corpse.

The Eastern Survivors and Aftershocks

While the Mediterranean coast burned and the Hittite Empire disintegrated, the Middle Assyrian Empire, located in modern northern Iraq, survived the crisis largely intact.

The Economy: Contraction, Not Collapse

The disruption of international trade affected Assyria differently than it did the West. Because they held the "Tin Road" and possessed agricultural independence, they weathered the storm.

The Tin Monopoly: As the western empires starved for tin, Assyria consolidated its control over the "Tin Road" leading from Afghanistan to Iran. They did not lose access to strategic metals; they simply lost their biggest customers.

The Loss of Luxury: The economic damage was exacerbated by the loss of Mediterranean imports. The flow of Egyptian gold and Mycenaean perfumed oil stopped. This caused a "prestige recession," but it did not threaten the state's survival.

Agricultural Independence: Unlike the Hittites, Assyria sat on the fertile plains of the Upper Tigris and enjoyed rain-fed agriculture. When the grain trade networks collapsed, Assyria could still feed itself.

The "Strangulation" hypothesis explains why the western empires fell first: they were at the end of the supply chain. However, the crisis eventually ricocheted back to the East. The disintegration of the Middle Babylonian Kingdom (Kassite Dynasty) about 1155 BC and the Elamite Empire about 1100 BC were the delayed casualties of the trade collapse.

Babylon: The Gold Famine (c. 1155 BC)

Dependent on Egyptian gold, which stopped flowing about 1250 BC, the Kassite dynasty withered and was sacked by Elam in 1158 BC.

Elam: The End of the Line (c. 1100 BC)

The Elamite Empire was the easternmost node of the network. Elam experienced a brief, "Golden Age" (c. 1160–1120 BC), based on plundering Babylon. However, this was unsustainable. With the Mycenaean and Hittite Empires gone, the global demand for tin collapsed. Elam was left holding huge quantities of raw materials with no one to buy them. The empire didn’t last. Unlike the other collapsing empires, Elam’s power diminished due to internal disputes within the royal family rather than because of invasion, “Peasant Revolt”, or famine. Elam was down but not out.

The Embers of Recovery: Seeds of the Iron Age

The "Strangulation" destroyed the Palace economies, but the "skeleton" of the network remained.

Gateway to the East

As noted above, the Middle Assyrian Empire weathered the storm. By holding the Tigris line and the "Tin Road" into the Zagros Mountains, Assyria preserved its connection to the Iranian Plateau and the Far East.

This survival meant that when the geopolitical chaos subsided, Assyria was the only power possessing an intact, veteran military and a functioning bureaucracy. This continuity allowed the Neo-Assyrian Empire to eventually reverse the flow of conquest, marching west to seize the Mediterranean ports to secure the goods they had been denied for centuries.

The trade routes through the Zagros, kept open by the Assyrian need for horses and tin, eventually facilitated the rise of the Medes and Persians. These Indo-Iranian peoples moved down the trade arteries to inherit the Mesopotamian sphere.

By 1100 BC, Elam was re-inventing itself as the Neo-Elamites who would be a significant power in the Middle East until the Assyrian campaigns of the 7th century BC.

The Cyprus Survival

Excavations at Tel Dor in Israel show continued trade in silver and ceramics with Cyprus during the subsequent "Dark Age". The Dor Hoard is a large silver hoard discovered at the ancient site of Tel Dor in Israel, dating to the second half of the 10th century BC. It consists of about 8.5 kg of silver and is a significant find for understanding trade and metallurgy in the Early Iron Age. This trade flowed primarily through Kition, which was strategically positioned to maintain the southern route to Egypt and the Levant even as the northern route to Ugarit remained dead.

The Phoenician Phoenix and Alternative Tin

With Ugarit (the northern hub) destroyed and Gaza (the southern hub) overrun by Philistines, a power vacuum opened in the Central Levant. The surviving Canaanite cities, specifically Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, filled this void.

Unlike the Palace-controlled fleets of the past, these cities operated as independent merchant republics. They revitalized the maritime link to Cyprus (Kition), securing the copper trade.

Because the inland routes were blocked by Aramean chaos and the breakdown of the Hittite/Egyptian order, these "Phoenician" cities were forced to look West. This necessity birthed the great expansion across the Mediterranean to Carthage and Spain, creating the maritime network that would define the Iron Age.

This maritime expansion reconnected the Middle East with alternative sources of tin. Tin deposits in Galicia, Brittany, and Cornwall had been used locally for centuries, but as the Phoenicians pushed west, they tapped into these Atlantic reserves. Shipwrecks off the coast of Israel (dated to the 12th century BC) containing western tin prove that this new supply chain was helping to replace the tin from the east.

The Egyptian Remnant: Holding the South

While Egypt lost its empire, it never fully lost the Southern Levant. The Via Maris as far as the ruins of Hazor remained a sphere of Egyptian influence. This tenuous grasp ensured that the route between the Nile Delta and the Phoenician coast remained known and traversable, eventually allowing the Neo-Babylonian Empire (under Nebuchadnezzar II) to later seize these routes and once more connect the Euphrates to Egypt.

The Greek Germination

In the Aegean, the survival of Athens and Lefkandi on the island of Euboea, about 50 kilometres north of Athens, proved critical. While Mycenae lay in ruins, Euboean pottery from the "Dark Age" has been found in the Levant.

After the collapse (LH IIIC), Mycenaean-style pottery didn't disappear; it became decentralized. Instead of uniform, high-quality export wares made in palace factories, local variations exploded across the Aegean and Levant.

Rhodes became a key node in the newly developing, decentralized, networks. It maintained contact with Cyprus (Enkomi/Kition) and the Philistine coast, bypassing the ruined palaces of the mainland.

As the Greeks entered their ‘Dark Age’, a thin "silver thread" of trade persisted, linking the Aegean survivors to the Phoenician coast. This tentative reconnection was the precursor to the Ancient Greek colonisation movement and the eventual economic dominance of the Greek city-states.

Technological Workarounds: Iron and the Alphabet

Finally, the scarcity of tin encouraged innovation.

Iron: The choking of the tin supply encouraged smiths to master the smelting of iron, a metal found almost everywhere. This did not result in an immediate replacement. Rather, it created a long overlap period. While bronze remained the superior material for elite armour, helmets, and lost-wax casting, iron became the "metal of the masses." This shift democratised warfare, armies were no longer limited by the scarcity of tin, allowing the Neo-Assyrians to field massive peasant infantries armed with iron spears and swords, forces vastly larger than the elite chariot corps of the Bronze Age. Their inscriptions show levies, local troops called up by provincial governors to supplement the standing army, armed with iron weapons, but the King and his elite guards are often depicted in bronze scale armour with bronze chariots.

Even hundreds of years later, the Homeric epics, written in the Iron Age but looking back to a ‘Greek Golden Age’, struggle to distinguish the two, often describing "bronze-clad" warriors fighting with "grey iron."

The Alphabet: With the fall of the Palaces, the complex Scribal bureaucracies (Linear B, Akkadian Cuneiform) vanished. In their place, the simplified Proto-Canaanite alphabet, portable, easy to learn, and adapted by the Phoenicians, became the lingua franca of commerce. This allowed for the decentralized, private trading networks that would knit the Iron Age Mediterranean together.

Conclusion

The Bronze Age did not end with a bang, but with a whimper. The strangulation of the trade routes, beginning at Hazor, tightening at Emar, and snapping at Ugarit, starved the great empires of the legitimacy and resources they required to rule.

When Ugarit finally burned about 1185 BC, it was not the start of the collapse, but the coup de grâce. Yet, in the darkness of the 12th century, the lights did not go out entirely. The routes through Assyria remained open, the Canaanites (Phoenicians) kept their ships afloat, and the Athenians held the line. These survivors, forced to adapt to a world without the Great Kings, forged a leaner, more resilient network, one built on iron, alphabets, and private enterprise. It was from these remnants that the new masters of the Middle East, from Nineveh to Athens, would rise.

References

Aubet, M. E. (2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bass, G. F. (1967). Cape Gelidonya: A Bronze Age Shipwreck. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.

Bell, about (2006). The Evolution of Long Distance Trading Relationships across the LBA/Iron Age Transition. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Ben-Dor Evian, S. (2017). "Egypt and the Levant in the Iron Age I–IIA: The Ceramic Evidence." Tel Aviv, 44(1).

Ben-Tor, A. (1998). "The Fall of Canaanite Hazor: The 'Who' and 'When' Questions." Mediterranean Peoples in Transition. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Ben-Tor, A. & Zuckerman, S. (2008). "Hazor at the End of the Late Bronze Age: Back to Basics." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 350, pp. 1–6.

Ben-Tor, A. (2013). "Who Destroyed Canaanite Hazor?" Biblical Archaeology Review, 39(4), pp. 27–36.

Broneer, O. (1966). "The Cyclopean Wall on the Isthmus of Corinth and Its Bearing on Late Bronze Age Chronology." Hesperia, 35(4), pp. 346–362.

Bryce, T. (2006). The Trojans and Their Neighbours. London: Routledge.

Cline, E. H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dikaios, P. (1969–1971). Enkomi Excavations 1948–1958, Vol. I–III. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Dickinson, O. (2006). The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BC. London: Routledge.

Faist, B. (2001). Der Fernhandel des assyrischen Reiches zwischen dem 14. und 11. Jh. v. Chr. (The Long-Distance Trade of the Assyrian Empire between the 14th and 11th Centuries BC). Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Finkelstein, I. (1988). The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Finkelstein, I. (2000). "The Philistine Settlements: When, Where and How Many?" in The Sea Peoples and Their World. Philadelphia: University Museum.

Kaniewski, D. et al. (2013). "Environmental Roots of the Late Bronze Age Crisis." PLoS ONE 8(8).

Karageorghis, V. (1990). The End of the Late Bronze Age in Cyprus. Nicosia: Pierides Foundation.

Knapp, A. B. & Manning, S. W. (2016). "Crisis in Context: The End of the Late Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean." American Journal of Archaeology, 120(1), pp. 99–149.

Kreimerman, I. (2017). "A Typology for Destruction Layers: The Late Bronze Age Southern Levant as a Case Study." in Crisis to Collapse: The Archaeology of Social Failure. Louvain: Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

Iakovidis, S. (1983). Late Helladic Citadels on Mainland Greece. Leiden: Brill. (See specifically the chapter on Athens).

Latacz, J. (2004). Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lemos, I. S. (2002). The Protogeometric Aegean: The Archaeology of the Late Eleventh and Tenth Centuries BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Manning, S. W. et al. (2023). "Severe multi-year drought coincident with Hittite collapse around 1198–1196 BC." Nature, 614, pp. 719–724.

Marom, N. & Zuckerman, S. (2012). "The Zooarchaeology of Exclusion and Expropriation: Looking at Ritual from the Trash in Late Bronze Age Hazor." Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 31(1), pp. 1–15.

Mazar, A. (2011). "The Egyptian Garrison Town at Beth Shean." in Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature. Brill.

Meirav Meiri, Philipp W. Stockhammer, Peggy Morgenstern, Joseph Maran. “Mobility and trade in Mediterranean antiquity: Evidence for an ‘Italian connection’ in Mycenaean Greece revealed by ancient DNA of livestock”, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 23, 2019, Pages 98-103

Middleton, G. D. (2020). Collapse and Transformation: The Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age in the Aegean. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Millek, J. (2019). Exchange, Destruction, and a Transitioning Society. Tübingen: Tübingen University Press.

Monroe, about M. (2009). Scales of Fate: Trade, Tradition, and Transformation in the Eastern Mediterranean ca. 1350–1175 BCE. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Morgan, about (1999). Isthmia VIII: The Late Bronze Age Settlement and Early Iron Age Sanctuary. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Mountjoy, P. A. (1993). Mycenaean Pottery: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

Radner, K. (2015). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sader, H. (2019). The History and Archaeology of Phoenicia. Atlanta: SBL Press.

Sherratt, S. (1998). "Sea Peoples and the Economic Structure of the Late Bronze Age in the Aegean." in Mediterranean Peoples in Transition. Jerusalem: IES.

Sherratt, S. (2003). "Visible Writing: Questions of Script and Identity in Early Iron Age Greece and Cyprus." Oxford Journal of Archaeology.

Sherratt, S. (2010). "The Trojan War: History or Bricolage?" in Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, 53(1), pp. 1–18.

Van De Mieroop, M. (2015). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Yadin, Y. (1975). Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible. New York: Random House.

Yahalom-Mack, N. et al. (2015). "The Beginning of Iron Production in the Southern Levant." Journal of Archaeological Science, 56.

Zuckerman, S. (2006). "Where is the Archive of Hazor? The Buried Secrets of the Tel." Biblical Archaeology Review, 32(6).

Zuckerman, S. (2007). "Anatomy of a Destruction: Crisis Architecture, Termination Rituals and the Fall of Canaanite Hazor." Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 20(1), pp. 3–32.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron