Civilisations that Collapsed

Did the Bronze Age Civilisations in the Middle East Collapse in 1200 BC ?

Did the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East collapse in 1200 BC or was it a long slow disintegration spread over hundreds of years? This series of articles argues for a period of decline starting 1350 BC and ending in 912 BC.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-04-18 | Last Updated 2025-11-20 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 2,044 times

Bronze Warrior on Horse

Did the Bronze Age Civilisations in the Middle East Collapse?

About 1200 BC, the Bronze Age civilisations around the Mediterranean collapsed. Or so one German historian thought back in 1817 AD. Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren wrote a history of ancient Greece in which he stated that the first period of Greek prehistory ended around 1200 BC, basing this date on the fall of Troy at 1190 after ten years of war (this estimate, based on flimsy evidence, is actually close to 1180 BC the now accepted date of the fall of Troy as narrated by Homer). Heeren then went on in 1826 to date the end of the Egyptian 19th Dynasty to around 1200 BC (actually 1187 BC).

Throughout the remainder of the 19th century AD other events were then subsumed into the year 1200 BC, including the invasion of the Sea Peoples, the Dorian invasion (which probably never happened at that time), the fall of Mycenaean Greece, and eventually, in 1896 AD, the first mention of Israel in the southern Levant recorded on the Merneptah Stele.

The Memeptah (Israel) Stele

Most of the text on what is sometimes known as the 'Israel Stele', glorifies Merneptah's victories over enemies from Libya and their Sea People allies, but the final two lines mention a campaign in Canaan, where Merneptah, a pharaoh in the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1213 to 1203 BC, says he defeated and destroyed Asqaluna (Ashkelon), Gezer, Yanoam and Israel.

Factors Involved in the 'Collapse'

During the 20th century and into the 21st, this historical dogma has adversely influenced how historians approached the subject of the 'collapse'. Today it is generally accepted that there were many factors involved including, in no implied order of significance; climate change that resulted in a drought and famine in some regions, migrations of people - both hostile and peaceful, invasion by hostile forces intent on immediate reward and/or territorial expansion, internal revolts within the city states, a collapse of the trading and communications networks, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and piratical raids by a confederacy of ethnic groups since labelled the 'Sea Peoples.'

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

What do we mean by Bronze Age Civilisations?

The definition of the word 'civilisation' as pertains to ancient societies, or rather when a society becomes a civilisation, has been debated for hundreds of years. The modern definition is 'an advanced state of human society, in which a high level of culture, science, industry, and government has been reached.'

But did the Bronze Sge societies see themselves as 'civilised' as we know the word? Or, perhaps more pertinently, did they recognise other contemporaneous societies as 'civilised'?

It is intriguing to see in written records of the time, that the various kings of the empires, city-states and palace-temples, did recognise a hierarchy amongst themselves. They referred to each other by regal and familial titles, implying that the recipient, and, by definition, his kingdom, was the social equal of the correspondent, or that the recipient was a lesser or superior entity, as the case may be.

Ambitious lesser entities vied to become the equal of, or greater than, their contemporaries. It is evident from the correspondence of the time, such as the Amarna and Mari letters, that lesser entities were often jealous of the prestige accorded to greater civilisations.

Understanding the Collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations

The collapse of civilisations of the Middle East remains one of the most intriguing and debated topics in archaeology and history. While there is no single definitive answer, a combination of factors is believed to have contributed to this period of widespread societal upheaval and decline.

However, recent research is showing that the 'collapse' was not a sudden event. The word collapse, invoking as it does the idea of a sudden calamity, is no longer the correct word to use.

Recent research and this series of articles, propose that the collapse was more a disintegration of some of the civilisations that existed during the late Bronze Age and their metamorphosis into different identities. In some cases, the disintegration was total, in others the disintegration led to a reduction in power and influence.

The factors that are normally considered when looking at the disintegration of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East can be divided into three types, environmental factors, political and socioeconomic factors, and external threats.

Environmental factors include climate change and natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and floods.

Political and socioeconomic factors include internal strife, overpopulation, and disruption of trade.

External threats include invasions, raids, and mass immigrations.

In addition to the factors mentioned above we will be looking at three other considerations and their contribution to the disintegration of the Bronze Age civilisations.

1. The Nature of the Civilisations

As far as possible we should consider the nature of the civilisation. How was the civilisation governed? Were the governors dictatorial or did they consider the welfare of their subjects. In other words, was the civilisation a 'top down' or a 'bottom up' society? Was there a massive gap between the top and the bottom? Were rewards filtered down through the social strata or were they concentrated at the top? Most importantly, and the most difficult to determine, is the question of how did the ruling elite view their society and, conversely, how did the bottom echelons see their society? We are looking for the potential for internal strife or, alternatively, internal bonding, either exacerbated by external threats or a threat from within the society itself.

2. Emergence of the Merchants

The emergence of a tenth (if you count the Canaanite city states and Cyprus as Bronze Age civilisations), subversive power in the region, a transregional network of merchants. We shall be looking at the merchants, the people facilitating trade on land and by sea, who gradually increased their power and matured from lackeys of the state to, in effect, an international middle class with almost autonomous powers.

3. The Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are an enigmatic entity whose raids and invasions have been portrayed as one of the primary causes of distress and tension within the cities and societies they afflicted and so, a major reason for the collapse of civilisations. The problem is, nobody knew then, or knows now, who the Sea People were. They were certainly not an identifiable tribal or societal group. The existence and motives of the Sea People must be examined.

Emergence of Bronze Age Civilisations and Societies in the Middle East

The Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East, in the order they are considered to have emerged are:

Mycenaean Civilisation (c 1750 BC)

Middle Babylonian Kingdom (c 1595 BC)

Kingdom of Mitanni (c 1550 BC)

Egyptian New Kingdom (c 1550 BC)

Canaanite city states (from c 1500 BC)

Cyprus (from c 1500 BC)

Hittite Empire (c 1430 BC)

Middle Assyrian Empire (c 1363 BC)

Elamite Empire (c 1210 BC)

The Canaanite city states are listed because each of the Canaanite city states, although independent, had reached a comparable level of civilisation as the rest of the traditional Bronze Age civilisations. Some would argue that they had progressed further and were on the brink of nationhood. For much of the late Bronze Age, the Canaanite city states were vassal states of neighbouring empires. In any case, the Canaanite city states were an intrinsic element in the disintegration of the Bronze Age civilisations and the emergence of new elites during the Iron Age.

During the following Iron Age period, from about 500 BC, the land of Canaan was known as Phoenicia and the Canaanites were known as Phoenicians. The division between Canaanites and Phoenicians around 1200 BC is regarded as a modern and artificial division, it is thought that the people now known as Phoenicians continued to consider themselves Canaanites throughout.

Cyprus is another anomaly. The Cypriot city states, like the Canaanite cities, had reached a comparable level of civilisation as the other Bronze Age states. For most of its history, Cyprus remained isolated from the rest of the Middle East. At different times during the late bronze age, both the Hittites and the Egyptians considered Cyprus a vassal state.

As with the Canaanite city states, Cyprus played an important role during the years of the disintegration of the bronze age civilisations.

I have taken the starting date for the rise of the Cypriot city states as 1500 BC, about the time Thutmose III of Egypt claimed Cyprus as a vassal state and imposed a tax on the island.

Both the Canaanite city states and Cyprus were catalysts in the events that led up to the Bronze Age collapse.

Middle East Civilisations at their Peak

The recognised Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East, excluding the Canaanite city states and Cyprus, in the order they are considered to have reached their peak, so, by definition, when their decline started, are:

Kingdom of Mitanni (c 1400 BC)

Egyptian New Kingdom (c 1380 BC)

Middle Babylonian Kingdom (c 1375 BC)

Hittite Empire (c 1330 BC)

Mycenaean Civilisation (c 1275 BC)

Middle Assyrian Empire (c 1225 BC)

Elamite Empire (c 1158 BC)

Disintegration of Bronze Age Civilisations and Societies in the Middle East

The Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East in the order they are considered to have disintegrated fully or partially at the end of the Bronze Age are:

Kingdom of Mitanni (c 1245 BC)

Hittite Empire (c1180 BC)

Middle Babylonian Kingdom (c 1155 BC)

Elamite Empire (c 1100 BC)

Egyptian New Kingdom (1077 BC)

Mycenaean Civilisation (1050 BC)

Middle Assyrian Empire (c 912 BC)

A simple comparison of the two lists shows that none of the Bronze Age civilisations emerged, reached their peak or collapsed in the same order or at the same time which implies a complicated, interconnected, and lengthy period of overall decline.

Five Hundred Years of Decline

I have taken the start of the decline as the year 1400 BC when the Kingdom of Mitanni was at its glorious height. The end date, 912 BC, marks the end of the Middle Assyrian Empire, the last of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East.

My reasons for this start date, I could have started earlier, are because that date marks the beginning of a series of events that together produced a domino effect that eventually, almost five hundred years later, resulted in the disintegration of the last of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East.

Some authors dramatically refer to the end of the Bronze Age as 'the perfect storm,' implying that a series of events occurred at the same time around 1200 BC, disintegrating one or more late Bronze Age civilisations. If that is the case, the 'perfect storm' lasted almost five hundred years, from c 1400 BC to 912 BC.

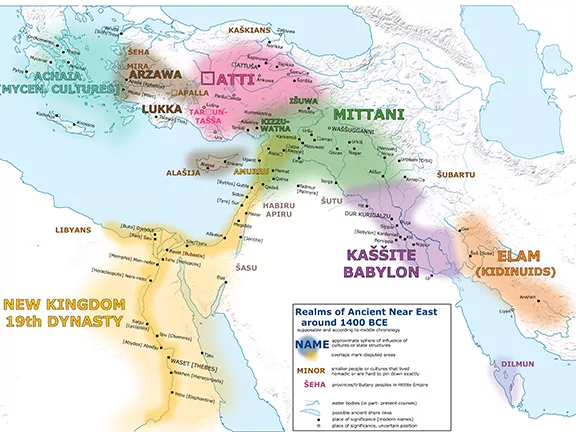

Mapping the Bronze Age Middle East

There were no maps marking political boundaries during the Bronze Age, they are a creation of the modern world. Nor did the peoples of individual empires or civilisations yet have the concept of nationhood, apart from a budding notion of the concept in the Canaanite city states as we shall see. Nationhood was to come much later and may yet prove to be a curse on modern civilisations.

If there are two words to describe the politics within the Middle East during the Bronze Age, they are volatile and fluid. Country boundaries did not exist. They are a modern invention that fail to consider physical geographical boundaries, the tribal nature of the people those boundaries are trying to segregate, different social norms, languages, religions and traditions and the often-nomadic existence of the very people the lines on the map are trying to corral.

The Nature of the Bronze Age Empires

With subtle variations, the Bronze Age empires of the Middle East consisted of powerful elites who had core territories that they controlled. The ruler was called a king although in modern day parlance, chief may be more accurate. On the boundaries of the core area was a zone of influence where there were city states. Each city state had its own ruler, sometimes also referred to as a king. The core area plus the outlying areas of influence have been termed empires.

Between the city states, nomadic tribes with no affiliation to empire or city state roamed at will. The Hapiru tribes that lived within the Bronze Age empires, mainly in the Fertile Crescent, would, in today's parlance, be termed terrorists.

The boundaries of the empires were constantly in flux due to competition from neighbouring empires and incursions by tribes that lived in the less hospitable regions on the outskirts of the empire.

The further the city states were from the core area, the less control the king could exercise. The further away from the core area they were, the more powerful the rulers of city states could afford to be. Each of the rulers of the city states vied with each other for prestige, territory, or advantage. In addition, many had diplomatic or trading relationships with the rulers of other empires acting on their own behalf. To bolster their own image, in correspondence and with their own subjects, these minor rulers often also called themselves king.

Of Shifting Alliances

Alliances and trade agreements were made between empires, between city states within an empire, between the empire and vassal city states, between vassal city states of different empires and between vassal city states of one empire with the king of another empire.

Those alliances were made and just as quickly broken as each party tried to benefit. Deception, hypocrisy, political intrigues, and downright lies were a normal part of negotiations as revealed in correspondence from the period such as the Hattusa Archives, the Mari letters, the Amarna letters, and the Ugarit texts.

National Identities?

During the Bronze Age, the people with a social status beneath the elite, whether urban or rural dwellers, had little or no sense of national identity. Their traditions and culture were centred on the family, community, and tribe. Apart from Egypt, where a world view of a cosmos centred on the Nile was exalted as the only place for Egyptian people, there were no nations as we know them today, or even the concept of nation.

Early writings give us only an indication of how the elites saw themselves and their subjects as 'different' to others. As we shall see, many of the kings of empires and city states granted themselves divine powers that were denied to all others. This could be a double-edged sword since, when things went wrong, people could and did blame the gods and by inference the king. When things were going well, the king, through his contact with a god or gods, could take the credit. It is interesting that the concept of divine right, divine rule and divine powers attached to monarchs survived into the modern age.

Exploring the Bronze Age Middle East

The only way to explore this ever-changing kaleidoscopic web of people, practices and 'political boundaries' is to take the region as a whole. In other words, ignore modern boundaries and look at a late Bronze Age history of the Middle East as a single entity.

References

Cline, Eric H. 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Hansen, Mogens G. "The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment." Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 10.2 (1997): 205-223.

Knapp, A. Bernard. "The Collapse of Mycenaean Greece: New Evidences, Old Questions." American Journal of Archaeology 109.3 (2005): 557-561.

Weiss, Harvey. "The Origins of the Bronze Age Collapse: A New Interpretation." The Biblical Archaeologist 47.3 (1984): 141-150.

Wiener, Malcolm H. "The Collapse of Complex Societies." Antiquity 73.281 (1999): 553-566.

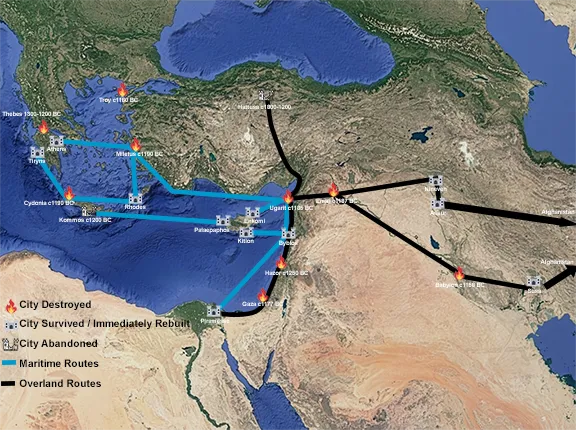

Alexikoua - Own work, data taken from: Atlas of World History, Patrick Karl O'Brien, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 019521921X, 9780195219210, page 37.

Biblical Archaeology - Collapse of Bronze Age Civilisations

Map Credit: Simeon Netchev / World History Encyclopedia

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron