Civilisations that Collapsed

The Development of Diplomacy Between Bronze Age Empires in the Middle East

As city-states gave way to empires, it became necessary for rulers to be able to communicate with each other. Diplomacy developed alongside the Bronze Age empires of the Middle East and was the 'glue' that bound these somewhat shaky edifices together. Bronze Age diplomacy was like nothing that had come before.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-05-3 | Last Updated 2025-11-23 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 7,324 times

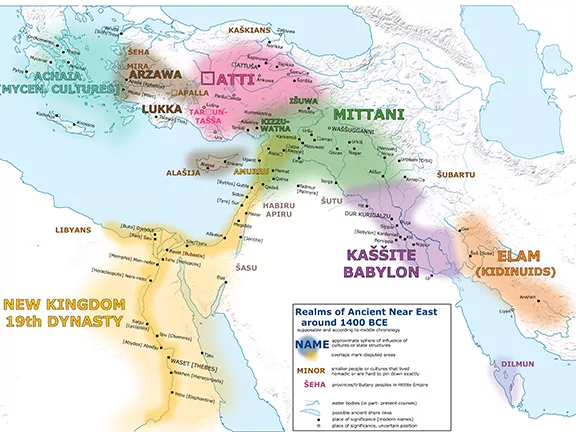

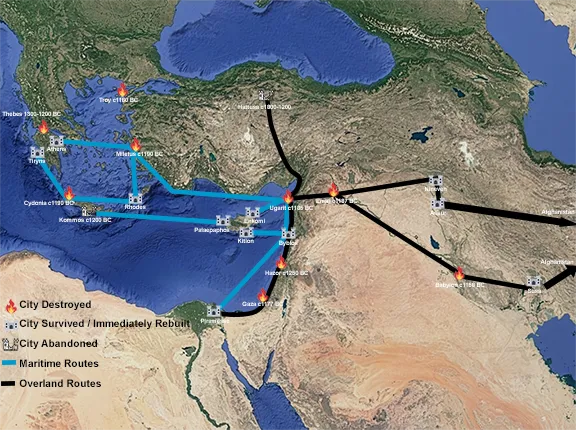

Map of the Middle East in the beginning of the Amarna letters period

Early Glimpses of International Relations in Mesopotamia

The earliest surviving evidence of international relations in Mesopotamia dates to the end of the Early Dynastic period (2600-2340 BC). These records primarily come from the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. Among them is the oldest known treaty, negotiated between the king of Lagash (En-metena) and his counterpart in Uruk, the capital city of Umma. The agreement was mediated by Mesilim, the king of another city-state called Kish.

The Sumerian Texts provide a rare glimpse into the culture, politics, and religion of the Sumerian civilisation, which was one of the earliest known civilisations in human history.

Lagash Texts written late 4th millennium BC to c 2334 BC

The most detailed accounts amongst the Lagash texts focus on the numerous conflicts between Lagash and its neighbour, Umma. These documents primarily detail military aspects with little mention of diplomacy. They highlight the constant rivalries between southern Mesopotamian city-states, possibly reflected in epic tales like those of the Uruk kings (Lugalbanda, Enmerkar, and Gilgamesh). These stories might be based on real events, highlighting the tensions between Lagash and rivals like Kish and Aratta. Kish appeared to hold some dominance at times. Its king, Mesilim, intervened around 2600 BC to mediate the Lagash-Umma conflict. Additionally, the title "King of Kish" was sometimes claimed by rulers of other cities, signifying a position of superiority.

The Treaty of Mesilim - 2550 BC

The Treaty of Mesilim is just one stele within the Lagash texts collection.

In the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, the floodplains of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers were home to a cluster of city-states known as the Sumerian civilisation. Lagash and Umma, two of the neighbouring city-states on the banks of the River Tigris near the Persian Gulf, were in a border dispute. The Treaty of Mesilim, inscribed on a stone stele in cuneiform script, records how a king of Lagash established a border between the two states that ran along the line of an irrigation canal. Inhabitants of Umma had, apparently, trespassed over the border and the treaty proposed the setting of boundary stones to firmly establish the border. The dispute rumbled on for two hundred years until the Umma king invaded and destroyed the city of Girsu, the capital of Lagash. A few years later, Sargon the Great, paying scant attention to boundary stones, conquered the whole of Sumer. Still, the Treaty of Mesilim is the first recorded legal agreement between states.

The Ebla Tablets written between c 2500 and 2250 BC

The richest source of diplomatic documents from this period comes from Ebla, located in modern-day Syria. Ebla's kings maintained contact with neighbouring rulers, including the powerful sovereigns of Mari and Nagar. Their diplomatic network extended further, encompassing rulers from Kish in Mesopotamia and even Hamazi in western Iran. Excavations at Ebla unearthed the oldest known written peace treaty, between Ebla and Abarsal. Evidence also suggests matrimonial alliances between Ebla's kings and some allies.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

From City-States to Empires: A Shift in Power

Southern Mesopotamia witnessed a gradual shift in power dynamics. Initially, city-states like Uruk under Enshakushana and Umma under Lugal-zagesi achieved temporary dominance over their neighbours. This culminated in the rise of Sargon of Akkad around 2340 BC who established the world's first empire, uniting all Mesopotamian city-states and stretching its influence into eastern Syria.

Details of diplomacy during this period remain scarce. However, a tablet records a peace treaty between Naram-Sin, Sargon's grandson, and his vassal king of Awan in southwest Iran. This Akkadian dominance persisted until the late 22nd century BC when the empire collapsed.

Several decades later, the Third Dynasty of Ur filled the power vacuum, establishing the Neo-Sumerian Empire. Unlike their Akkadian predecessors, these rulers actively fostered communication with neighbouring kingdoms. Regular embassies were exchanged, demonstrating a more diplomatic approach. A high official oversaw this diplomatic service.

The Neo-Sumerians combined military campaigns on the Iranian plateau with strategic marriages. Marrying their daughters to rulers of regions like Anshan and Zabshali secured loyalty and bolstered their legitimacy. However, this empire eventually disintegrated, ushering in a period without a dominant power under the Amorite dynasties.

The Rise of Rival Kingdoms and the Power Shift

The second millennium BC witnessed a shift from a single dominant power to a more balanced international landscape. No single kingdom held absolute sway, paving the way for the emergence of several powerful and stable states. These new powers dominated their regions and held varying degrees of control over vassal states, though these allegiances often fluctuated over time. Rivalries between the dominant kingdoms frequently arose over these vassals, sometimes erupting into open conflict.

The Amorite Era (2004-1595 BC)

The first half of the millennium was marked by the Amorite kingdoms. These kingdoms, flourishing from 2004 to 1595 BC, established a kind of common ground for political practices across a vast region stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Zagros Mountains. Mesopotamia and Syria witnessed the rise and fall of several dominant kingdoms. Initially, Isin and Larsa, successors to the Ur empire, held sway. However, Babylon eventually emerged as the dominant power under Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) and his successors, while Elam's attempts at regional dominance ultimately failed. In Syria, the kingdom of Yamhad (Aleppo) enjoyed a period of prominence, benefiting from the decline of its rivals Mari and Qatna during the 18th and 17th centuries BC.

The Kanesh Archives written between 1920 and 1850 BC

The Kanesh archives offer a unique window into daily life during the Amorite era, containing a wide variety of documents including business contracts, letters, and even personal records. They provide insights into trade practices and the diplomatic manoeuvres that facilitated trade during this period, family life, and even the emotional struggles of individuals living far from home.

Kultepe-Kanesh was a city state in the middle of Anatolia near modern day Kayseri in the centre of what would become the Hittite Empire. The city contained a large Assyrian karum, or colony, who organised the Assyrian trading network in Anatolia. The karum was composed of families that hailed from Assur, some 775 kilometres away. There were over twenty such karums in Anatolia alone. Kultepe became a key centre of culture and commerce between Anatolia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. The private archives of the karum merchants have yielded 23,500 clay tablets and envelopes to date, including some that deal with the establishment of what would be termed a corporation or limited company in modern parlance.

Royal Archives of Mari written between c 1900 and c 1700 BC

Our understanding of diplomatic practices during this era comes primarily from the exceptional royal archives of Mari, dating to the mid-18th century BC. These archives contain a wealth of diplomatic correspondence, political agreements, and historical records. Supplementary information is gleaned from smaller archives like those found at Tell Leilan, Tell Rimah, and Kultepe.

The Rise of New Powers (17th-12th Centuries BC)

The main kingdoms of the Middle East during the 13th century BC

The Amorite period ended with the destruction of its two major kingdoms by the Hittites, who had consolidated control over eastern Anatolia by the late 17th century BC. Concurrently, the Hurrians established increasingly powerful political entities, culminating in the formation of the kingdom of Mitanni. These two emerging powers, along with Egypt, ushered in a new era characterized by larger, more powerful, and culturally diverse kingdoms. Following the expulsion of the Hyksos by the 18th dynasty, Egypt launched military campaigns into the Levant several decades later, expanding its empire until it bordered Mitanni.

This shift marked a new balance of power. Most of the former Amorite kingdoms became vassals to these new dominant forces, with the notable exception of Babylon, which remained a significant power under the Kassite dynasty (1595-1155 BC). The rulers of these dominant kingdoms were considered "great kings" amongst themselves, operating on an equal footing. By the 14th century BC, Assyria had replaced Mitanni as one of these major powers. Elam, particularly during the 13th and 12th centuries BC, could also be considered a significant player on the international stage.

A Rich Tapestry of Diplomatic Records

Our understanding of diplomatic practices during this period is enriched by several exceptional sources.

The Hattusa Archives written during the 2nd millennium BC

Unveiling the history of Hattusa beyond the 14th century BC are the Hattusa Archives, otherwise known as the Bogazkoy Archives, a treasure trove unearthed during excavations in 1906 AD. This archive houses an impressive collection of over 30,000 clay tablets, covering a period from roughly 1430 BC to the fall of the Hittite kingdom around 1190 BC.

The archive provides a window into various aspects of Hattusa's life. It contains royal chronicles, treaties with other nations, political correspondence, legal documents, administrative records, and even religious and mythological texts. Notably, it holds a copy of one of the earliest known international peace treaties, the agreement between the Hittites and Egyptians following the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC. Additionally, the archive includes letters exchanged with neighbouring powers like the Assyrians, Mitanni, and Amurru.

The Hattusa Archives contain subsets, collections of texts relating to one king or historical event. These subsets include, the Ahhiyawa Texts, the Deeds of Suppiluliuma, and the Plague Prayers.

The Ahhiyawa Texts written between c 1430 and 1210 BC

A significant part of the Hattusa Archives are a collection of tablets known as the Ahhiyawa texts. These texts, dating from the 15th to 13th centuries BC, refer to a land called Ahhiyawa, which many scholars believe corresponds to the Mycenaean world of Greece. The Ahhiyawa texts are mainly concerned with various conflicts between the Hittite Empire and Ahhiyawa, written from the Hittite perspective. These accounts are believed to be the basis for Homer's epic poems about the Trojan War and the siege of Troy.

Masat Hoyuk Tablets c 1425 to 1390 BC

Masat Hoyuk was a Bronze Age city about 100 kilometres east of the Hittite capital of Hattusa. The collection of 117 tablets and fragments of tablets mainly date to the 14th century BC and record correspondence between Masat Hoyuk and the royal court at Hattusa over a very short period, from two to ten years, sometime during the reign of Tudhaliya II (c 1425 - 1390 BC). Some of the letters deal with a famine near a settlement called Kasepura. The sequence of events can be reconstructed roughly as follows.

The Famine at Kasepura

Locust swarms have destroyed much of the crops in the Kaska territory, forcing Gasgaeans to raid fields surrounding Hittite towns. They harvest the grain, attack royal storerooms, kill cattle and abduct people. In order to relieve the plight of the population, the Hittite king then orders grain to be taken from royal storerooms in Maresta that was originally intended for sowing.

Other letters refer to 'the matter of enemies' and the 'matter of troops'. Of particular interest are the names of the correspondents and addressees, some of whom belong to the immediate king's circle.

Deeds of Suppiluliuma (1350 - 1322 BC)

Suppiluliuma usurped the throne from his older brother, Tudhaliya III, who was murdered. He subsequently married a Babylonian princess and banished his previous wife to Ahhiyawa territory. He was a warring king extending the Hittite empire down into Syria where he eventually got into conflict with the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten, 1353 to 1334 BC. In 1322 BC, he died from a plague brought to Hatti (land of the Hittites) a few years earlier by Egyptian prisoners of war. Mursili II later recorded the death and plague on tablets known as the 'Plague Prayers.'

The Aegean List inscribed about 1370 BC

The Aegean List refers to a 'tour' (during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, 1391 to 1353 BC) to the Greek islands and mainland probably around 1370 BC, some twenty years prior to the final destruction of Knossos, capital city of the Minoans, in 1350 BC.

The Minoans were for many centuries very influential throughout the eastern Mediterranean including Egypt. In what was a probably diplomatic mission, the Egyptians went to cement relations with an old trading partner, the Minoans, whom they visited first on Crete (the Egyptians called it Keftiu) then travelled to mainland Greece (that they called Tanaja) visiting the island Kythera in the southeast and then to Mycenae and its port city of Nauplion, and on to the region of Messinia (Pylos) and possibly Thebes in Boeotia and returning through Crete.

The list was inscribed on a statue base, the remains of which were found at a necropolis at Kom el-Hetan, across the Nile from the city of Thebes, modern Luxor.

The mission was also taken to meet with the Mycenaeans who were newcomers to the trading network.

During this period, the Hittites were expanding their power base, no doubt disconcerting the Egyptians.

The diplomatic mission may also have involved securing Greek support, possibly as allies, or at the least encouraging the Greeks to continue their incursions into western Anatolia to maintain Hittite focus away from their southern border with Egypt.

The Amarna Letters written between 1360 and 1332 BC

The Amarna Letters are a collection of clay tablets discovered in Egypt, dating back to the 14th century BC. They are mainly letters exchanged between rulers in the eastern Mediterranean, including pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten of Egypt and leaders of Canaanite city-states. They deal with issues like diplomacy, trade, military threats, and requests for assistance. The letters are written in Akkadian, a Mesopotamian language, showing its use as a common tongue for diplomacy at the time. The archive also includes myths, epic tales, and educational materials related to cuneiform writing, the writing system used on the tablets.

Royal Archives of Ugarit written between c 1260 and c 1190 BC

Additionally, the royal archives of Ugarit, a minor Syrian kingdom controlled by both Egypt and the Hittites at various times, provide valuable information. This period boasts the most abundant and geographically diverse sources for the study of international relations in the ancient world.

The Language of Diplomacy in the Ancient Middle East

Our understanding of diplomatic practices in the ancient Middle East primarily comes from royal archives of the second millennium BC. These archives, unearthed at four key archaeological sites, Mari, Hattusa, Tell el-Amarna, and Ugarit, provide the most extensive information. Limited sources exist from the preceding millennium (Lagash, Ebla) and the following (Nineveh, Hebrew Bible). The focus on the second millennium reflects both the abundance of source material and the particularly dynamic nature of international relations during that period.

A Family of Rulers - The Great Powers Club

Kings in the second millennium often viewed themselves as an extended family. Suzerain kings were considered "fathers" (abu in Akkadian) to their vassals, who were referred to as "sons" (maru). Sovereigns of equal rank, whether "great kings" or vassals of the same suzerain, addressed each other as "brothers" (ahu). The relationship between suzerain and vassal was further emphasized by terms like "master" (belu) and "servant" (wardu). This familial language reflects the ideal dynamics between rulers' affection, protection from the suzerain (father) and obedience, respect, and tribute from the vassal (son). Equality between rulers was fostered through reciprocity, with an emphasis on gift-giving and exchange.

Over time, a new category of kings emerged, those without a human suzerain (answering only to the gods). These powerful monarchs began using the title "great king" (sharru rabu) in the latter half of the second millennium. This elite group, described as a "closed club" by scholars like H. Tadmor and M. Liverani, determined who could join based on military success. For example, Assur-uballit I of Assyria earned his place among the "great kings" by defeating Mitanni, while Tarundaradu of Arzawa (eastern Anatolia) remained excluded due to his failure to conquer the Hittites. This hierarchy naturally influenced diplomatic relations, as each king sought alliances and connections with their peers.

Royal Messengers: The Backbone of Ancient Diplomacy

Diplomatic relations in the ancient Middle East relied heavily on royal messengers, known as "mar ipri" in Akkadian. Empowered by their kings, these individuals played a critical role in fostering communication and building connections between royal courts. While messengers sometimes included merchants travelling for personal business or even high-ranking officials, the core group hailed directly from the royal palace.

More Than Just Message Carriers

These messengers served as the backbone of diplomacy. They carried official messages and delivered gifts entrusted to them by their rulers. However, their duties often extended beyond simple delivery. Messengers with special skills or the king's confidence could be entrusted with negotiating political agreements or arranging marriages between royal families. The level of autonomy they enjoyed varied based on the circumstances. Some functioned primarily as couriers, while others functioned as ambassadors with the authority to negotiate on the king's behalf.

Travel, Protocol, and Security

Messengers undertook their journeys on foot, by donkey, by chariot, or even by ship. Upon arrival in a foreign court, they were welcomed and provided lodging in designated buildings, typically separate from the royal palace. The kings were paranoid about having spies in their camp. Their stay was funded by the host country, and they might be granted audiences with the sovereign to deliver messages and gifts. Interestingly, these audiences were public events, potentially attended by foreign dignitaries, even those representing rival nations.

Masters of protocol, messengers needed to adapt to the customs of their hosts, understanding the high stakes and potentially severe consequences of missteps. The duration of their stay was determined by the host, with some missions lasting months or even years, as documented in the Amarna letters. Upon returning home, a messenger was often accompanied by an escort from the host country to ensure safe passage and verify the information he carried.

For more on the first bronze age courier services.

Specialists in the International Arena

While there was no concept of permanent ambassadors residing in foreign courts, some high-ranking individuals might specialise in managing relations with a specific kingdom. They would develop residences and connections within that court, fostering a deeper understanding. The Egyptian official Mane, who frequented the court of the Mitanni king Tushratta during the Amarna era, exemplifies this specialised role. Additionally, some individuals developed expertise in international relations, earning a degree of immunity during their travels. Attacks or mistreatment of messengers were considered serious offences and often sparked outrage among other kings. Archaeological discoveries at Mari and Tell el-Amarna unearthed examples of "laissez-passer" documents specifically intended for these messengers. Even in courts where foreign messengers were not granted audiences, they were still obligated to provide them with lodging. In Mari, such travellers were referred to as "etiqum" (messengers in passage.

The Language of Diplomacy: Written Records and Communication

Maintaining clear and unbiased communication between rulers was crucial for fostering proper diplomatic relations in the ancient Middle East. This need gave rise to the extensive use of written diplomatic tablets, unearthed at numerous archaeological sites. These messages, typically composed in Babylonian Akkadian, the lingua franca of the region since the early second millennium BC, followed a standardised format. They began with a simple introduction identifying the sender and recipient using the Akkadian formula "ana X qib?-ma umma Y-ma" (meaning "To X say: Thus spoke Y").

During the latter half of the second millennium BC, diplomatic messages evolved to incorporate more elaborate greetings. "Great Kings" would exchange well-wishes for happiness and prosperity for their counterparts and their royal houses. Vassals, on the other hand, used greetings that emphasized their submission. A common vassal formula involved declaring prostration "at your feet seven times and seven times more."

Gifts and Prestige: The Currency of Diplomacy

Royal envoys often brought gifts to their hosts. Sovereigns might demand tribute from vassals, both routinely and at their discretion, creating an unequal power dynamic. However, relations between equals necessitated a balanced exchange. Gifts received had to be met with gifts of comparable value, establishing a system of reciprocal giving and receiving (known as subultum and surubtum in the Amorite period).

A letter unearthed at Mari is an example of this principle. The king of Qatna complains to his counterpart in Ekallatum for failing to reciprocate his gifts with items of equal worth. He acknowledges that such complaints typically go unspoken but feels compelled to address the imbalance. He worries that other rulers, learning of the situation, might perceive him as weakened by the exchange. Prestige, therefore, was a serious concern in diplomatic gift-giving. The Amarna letters reveal similar conflicts arising from gift exchanges.

The types of goods exchanged often mirrored those found in international trade. During the Amorite period, Elam sent tin from Iranian mines as gifts, while the Egyptian king in the Amarna era offered gold from Nubia, and the king of Alashiya (likely Cyprus) provided copper. These prized metals were a subject of intense negotiation in the Amarna letters, suggesting a degree of dependence on these exchanges. Manufactured goods like vases, jewellery, thrones, and chariots were often exchanged as part of the package.

Some scholars argue that these exchanges amounted to disguised trade, with the return gift serving as payment for the initial offering. However, the emphasis on reciprocity in these negotiations suggests a more complex dynamic, where both economic and symbolic aspects played a role. Beyond traditional commodities, diplomatic gifts could include works of art, exotic animals, or prized horses. The Amarna letters mention Tushratta of Mitanni sending a statue of the goddess Ishtar from Nineveh to Egypt, possibly as a gesture of appeasement to Pharaoh Amenhotep III.

In specific instances, people could also be sent as gifts. Vassals might be obligated to send servants to their suzerain's court as tribute. Ramses II, for example, sent a physician to the Hittite court of Hattusili III. These exchanges of personnel likely occurred within the context of alliances, particularly those forged through dynastic marriages, and may not have followed the strict reciprocity principle of gift-giving.

Ancient Treaties: Oaths, Rituals, and Pacts on Clay

Treaties served as a crucial tool in diplomacy throughout the ancient Middle East. These agreements, known by various names in different languages, typically followed periods of war and aimed at establishing peace. While not always written down, written treaties emerged quite early. One of the earliest known examples dates to the 24th century BC, between the cities of Ebla and Abarsal, with the involvement of Naram-Sin of Akkad and an Elamite king.

Numerous tablets detailing protocols for oaths of alliance between kings were produced during the Amorite period. These tablets originated from locations like Mari, Tell Leilan, Kultepe, and some of unknown provenance (alliances between Shadlash and Nerebtum, Eshnunna and Larsa, and Uruk). The following period saw treaties documented in texts unearthed at Alalakh, Ugarit, and most notably, the Hittite capital Hattusa.

A Treaty between Hattusili III and Ramses II

The treaty between Hittite king Hattusili III and Egyptian king Ramses II holds unique significance as it exists in both an Akkadian version on clay tablets and an Egyptian hieroglyphic copy, the only known instance of a treaty found at both parties' locations.

The Neo-Assyrian period yielded international treaties from Nineveh, with another linked by an Aramaic inscription to Sfire.

Oaths witnessed by Gods

While written records were not always a necessity for concluding a diplomatic accord, oaths witnessed by the gods were paramount, binding each party to the agreement. "Treaties" from the Amorite period functioned as protocols for these oaths, often reinforced by rituals. These rituals could involve a shared sacrifice following a banquet if both parties were present, or a "lipit napistim" (throat touching) ceremony if an in-person meeting were impossible. This ritual is not known to have been practiced in other periods.

Hittite Treaties

The Hittites placed greater emphasis on written treaties. Certain treaties included detailed clauses outlining the parties involved, the agreement's provisions, a list of the deities serving as guarantors, and potential curses for those who breached the contract. Hittite treaties also incorporated a section detailing the historical context that led to the agreement.

Treaty clauses typically addressed the conditions of peace between parties. This could encompass the movement of people between kingdoms, the return of prisoners, or even the expulsion of political refugees. Alliances were also established, often following the formula of "being friends with friends and enemies with enemies."

The hierarchy of kings was reflected in the clauses. Agreements between equal rulers were symmetrical, while those between a suzerain and a vassal were unequal. Vassalage treaties (primarily documented in the Hittite and Assyrian spheres) outlined the conditions of one kingdom's submission to another. These stipulations could include restrictions on independent foreign policy, obligatory tribute payments, military assistance to the suzerain upon request, and, in some cases, permitting the suzerain to station troops on their soil.

The 19th-century BC treaties concluded by the merchant city of Assur even included clauses related to economic activities, such as taxation and merchant security.

Marriages for Kingdoms: Dynastic Unions in the Ancient Middle East

Dynastic marriages served as a cornerstone of diplomacy in the ancient Middle East. Evidence of this practice dates to the Ebla archives of the archaic period but becomes especially prevalent in the second millennium BC. These unions aimed to forge or strengthen ties between royal families. Polygamous kings might have multiple wives, including daughters or sisters of other rulers. The custom dictated that the woman would leave her home court to join her husband's.

Marriages could occur between kingdoms of equal or unequal rank. Suzerains might offer their daughters to vassals, and vice versa. These women would then become part of their new spouse's harem. Great kings often sought to ensure their daughters held prominent positions within their new courts. Ideally, they would become the primary wife, enabling them to exert political influence. The Hebrew Bible portrays Jezebel, daughter of the king of Tyre who married King Ahab of Judah, as an example of this strategy

However, such success stories were not guaranteed. A study of the daughters of King Zimri-Lim of Mari, who married into other Syrian Amorite kingdoms, reveals varying degrees of influence.

While participation in these matrimonial exchanges was generally expected of sovereigns, the Egyptian kings of the Late Bronze Age are a notable exception. They refused to allow their daughters to marry foreign rulers, even equals, while readily accepting foreign princesses as brides themselves. In these cases, they disregarded the principle of reciprocity.

The process of arranging these dynastic marriages is well-documented in records unearthed at Mari, Tell el-Amarna, and Hattusa (for marriages between equals).

First, negotiations commenced, including the selection of the bride. The future father-in-law typically initiated the process, although sometimes the future husband took the lead. These negotiations were conducted through correspondence delivered by the most trusted messengers or ambassadors available.

Dealing with the mother-in-law

An exceptional instance involved the marriage of Ramses II and the daughter of Hattusili III, where the Hittite queen Puduhepa directly negotiated with the Egyptian queen. However, such female involvement was uncommon.

The Role of Envoys

Envoys were tasked with negotiating the dowry but also with assessing the bride's beauty, a key quality sought after by grooms. The dowry (nidittum in Old Babylonian), offered by the bride's family, was a subject of intense negotiation, often accompanied by a counter-dowry (terhatum in Old Babylonian), offered by the groom's family. Archaeological finds at Mari and Tell el-Amarna include lists detailing these dowries and counter-dowries.

The Wedding

Once the arrangements were finalised, the princess would permanently depart her home court to join her husband's. She would travel with her entourage, including representatives from both her own court and her fiancé's. The wedding ceremony typically occurred after her arrival. Following the marriage, she could maintain contact with her family through letters or visiting envoys. Her family would anxiously await news of her bearing children, particularly sons, for her husband.

The Glue That Held the Bronze Age Empires Together

The glue that held the Bronze Age empires together was a 'two part' glue with one not able to do the job without the other.

As we saw in the previous chapter, the first part of the glue were the trading networks that had encouraged the rise of cities, strategically placed to take advantage of trade through that geographical location. The cities, city-states and empires that followed, depended on the trading networks to survive economically.

For more on the first Bronze Age trading networks.

International relations and diplomacy were the second component of the 'glue' that held the sometimes unstable empires together.

When the glue failed, conflict was almost inevitable. As Carl von Clausewitz famously stated, “War is merely the continuation of politics by other means."

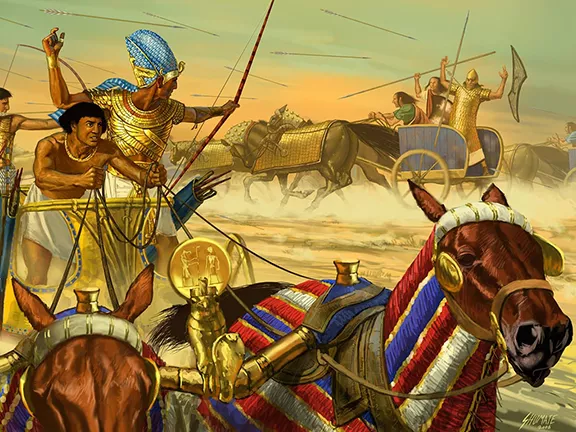

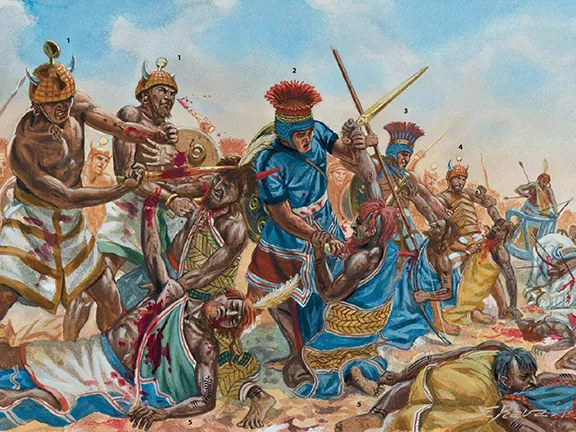

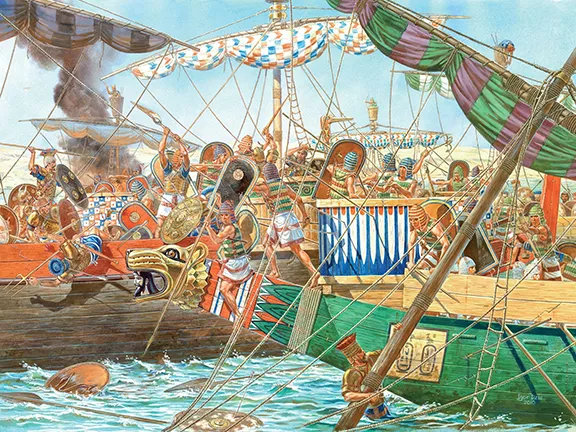

Bronze Age Warfare

Warfare is a non-productive policy, costly to both the aggressor and defender in terms of materials, resources, and manpower. The aims of a Bronze Age aggressor were base, to increase their wealth and stock of necessities by plundering the defender. Their secondary aim was to increase their population tax base by taking captives or taking control of a population centre along with its rural outskirts. In the latter case, warfare often resulted in a decimated city and a ruined hinterland lacking sufficient urban or rural population to rejuvenate itself.

In many cases, the conquered city-state became a vassal city-state of the aggressor. In some instances, the defending king was reinstated on his throne. This policy sometimes worked and sometimes backfired.

Vanquished vassal city-states were expected to contribute wealth in the form of taxes and commodities, artisans and craftspeople, and armed forces, to the conquering city-state.

The exception, fortunately rare even in the Bronze Age, was the elite ruler who was only concerned with personal aggrandisement and glory, for its own sake or to take his populations' attention away from domestic problems.

Each city-state, and later, empire or kingdom, had to maintain a defence force of one form or another to deter and, when necessary, defend the homeland, itself a huge expense.

More information about the development of maritime and land-based trade networks can be found here.

A Small World System

By 1400 BC, when the first of the Great Powers, the Kingdom of Mari, was about to be overcome, the Great Powers had established a small world system. That is a system of communication that involved no more than three contact points to allow contact between any two powers, even though they may never have communicated directly. Why is this important? Well, this has only occurred twice in world history. The second time it happened is in the modern world, today. It makes you think, doesn't it?

References

Artzi, P. "The influence of political marriages on the international relations of the Amarna-Age," in J.-M. Durand, ed., op. cit. 23-36;

Beckman, G. "International Law in the Second Millennium: Late Bronze Age", in R. Westbrook (dir), op. cit., p. 753-774; T. Bryce, Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East: The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age, New York and London, 2003.

Beckman, G. Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Atlanta, 1996; (fr) W. L. Moran, Les lettres d'El Amarna [The letters of El Amarna], Paris, 1987; (it) M. Liverani, Le lettere di el-Amarna [The letters of El Amarna], 2 vol., Padua, 1998 & 1999;

Beckman G. M., Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Atlanta, 1999, p. 92.

Biga, M. G. "The Marriage of Eblaite Princess Tagris-Damu with a Son of Nagar's King," in M. Lebeau, ed., About Subartu, Studies devoted to Upper Mesopotamia, 1998, 17-22;

Briend, J. R. Lebrun, and E. Puech, Traites et serments dans le Proche-Orient ancien [Treaties and oaths in the ancient Near East], Paris, 1992;

Cohen, R. and R. Westbrook, ed. Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginning of International Relations, Baltimore and London, 2000; (de) E. B. Pusch and S. Jakob, "Der Zipfel des diplomatischen Archivs Ramses II" [The Diplomatic Archives of Ramses II], in Egypten und Levante XIII [Egypt and Levant XIII], 2003, 143-153;

Cooper, J. International Law in the Third Millennium, in A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law, vol. 1, ed. R. Westbrook, Boston and Leiden, 2003, p. 241-251.

Cooper, J. The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict, Malibu, 1983.

Gunbatti, C. "Two Treaty Texts found at Kultepe," in J. G. Derckson, ed., Assyria and Beyond: Studies presented to Morgens Trolle Larsen, Leiden, 2004, 249-268.

Holmes, Y. L. "The Messengers in the Amarna Letters," in Journal of the American Oriental Society 95, 1975, 376-381;

Horne, C. F., (2010) The Sumerian Texts. The Royal Inscriptions of Lagash (3000 BC). Publisher: Kessinger Publishing.

Hout, Theo van den. 'Some observations on the tablet collection from Masat Hoyuk'

Kings I, 16:31

Liverani, M. Prestige and Interest, International Relations in the Near East, 1600-1100 B.C., Padua, 1990;

Liverani, M. "The Great Powers' Club," in R. Cohen & R. Westbrook, ed., op. cit., 15-24.

Marchesi, G. "Goods from the Queen of Tilmun", in G. Barjamovic, J. L. Dahl, U. S. Koch, W. Sommerfeld, et J. Goodnick Westenholz, Akkade is King: A collection of papers by friends and colleagues presented to Aage Westenholz on the occasion of his 70th birthday 15th of May 2009, Istanbul, 2011,p. 189-199.

McCarthy, D. J. Treat and Covenant, a study in form in the Ancient Oriental documents and in the Old Testament, Rome, 1978;

Oller, G. H. "Messengers and Ambassadors in Ancient Western Asia," in J. M. Sasson, ed., Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York, 1995, 1465-1474;

Parpola, S. "International Law in the First Millennium," in R. Westbrook, ed., op. cit., 1047-1066.

Parpola, S. and K.Watanabe, Neo-Assyrian Treaties and Loyalty Oaths, Helsinki, 1988.

Parpola, S. et K. Watanabe, Neo-Assyrian Treaties and Loyalty Oaths, Helsinki, 1988, p. 24-27.

Image References

Map of the Middle East in the beginning of the Amarna letters period, the first half of the 14th century BC. The extension of the dominions of the great kingdoms is approximate. Remarks : the extension of the Arzawa is not shown because of its uncertainty, it may have covered the main part of Western Anatolia ; the Ahhiyawa are here supposed to be the "Mycaneans" ; the extension of Elam is very approximate.

By Middle_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhur (talk)derivative work: Zunkir (talk) - Middle_East_topographic_map-blank.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12053247

Map showing the approximate extension of the main kingdoms of the Middle East during the 13th century BC, with the main cities and archaeological sites, and some regions.

By Middle_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhur derivative work: Zunkir - Middle_East_topographic_map-blank.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12048950

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron