Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

Late Bronze Age shipreck off Uluburun (1335 - 1305 BC)

The Uluburun ship yielded the world's largest Bronze Age collection of raw metals ever found, enough copper and tin to produce 11 metric tons of bronze of the highest quality

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-24 | Last Updated 2025-09-19 | Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 10,867 times

Reconstruction of the cargo hold of the Uluburun ship

Where was the Uluburun wreck found?

In the summer of 1982, Mehmed Cakir, a local sponge diver from the village of Yalikavak near Bodrum, discovered the Uluburun shipwreck off the east shore of Uluburun (Grand Cape), Turkey. This Late Bronze Age shipwreck, which dates back to the late 14th century BC, sank in the Mediterranean Sea.

The latitude and longitude of the Uluburun shipwreck site are 36.42.30 N 27.17.30 E. It is located about 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) off the coast of Uluburun, a small village in the Mugla Province of Turkey.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

About the Uluburun wreck site

The Uluburun shipwreck was found in a remarkably good condition, considering its age. The ship's hull was largely intact, and much of the cargo was still in place. This was because the ship sank in relatively shallow water, and the cargo was protected by a layer of sand.

Who excavated the Uluburun shipwreck?

Raising the copper ingots

The Uluburun shipwreck was excavated by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) between 1984 and 1994. The excavation was led by George Bass, the founder of the INA. The excavation was a major undertaking, requiring the use of specialized diving equipment and techniques.

When did the Uluburun wreck sink?

Based on the pottery and other artifacts found on the wreck, archaeologists have determined that it sank sometime between 1335 and 1305 BC.

The pottery includes Mycenaean, Cypriot, and Levantine vessels, all of which date to this period. The other artifacts include a scarab seal with the name of the Egyptian pharaoh Nefertiti, which further narrows the earliest date of sinking to between 1353 and 1334 BC.

How was the Uluburun ship built and what were its dimensions?

The Uluburun ship was built with planks of Lebanese cedar that were joined together with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. The planks were then caulked with bitumen to make them watertight. The ship had a single mast and a square sail. The hull was about 15 meters long and 5 meters wide.

As part of the shipboard gear, the Uluburun carried 24 stone anchors of a design that was common in the Levant and occasionally seen in the Aegean. The anchors served as ballast along with other stones found serving the same purpose. This superfluity is necessary, ancient crews would cut an anchor rope, rather than pull the anchor in, if conditions at the anchorage was putting the ship into danger, off a steep coast for instance.

Who were the people who owned and operated the ship?

The people who owned and operated the Uluburun ship are unknown. However, there are a few clues that can be gleaned from the cargo and the ship itself.

The cargo of the Uluburun ship suggests that it was owned and operated by a group of merchants who were involved in the long-distance trade of copper, tin, and other goods. The ship was also carrying a cargo of gold jewellery and other luxury goods, which suggests that the merchants were wealthy and well-connected.

The ship itself is also a clue to its ownership. The Uluburun ship was a large and well-built vessel, which suggests that it was owned by a wealthy merchant or group of merchants. The ship was also equipped with a variety of navigational tools, which suggests that the merchants were experienced sailors.

Based on these clues, it is possible that the Uluburun ship was owned and operated by a group of Mycenaean merchants. The Mycenaeans were a wealthy and powerful civilization that controlled much of the trade in the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean. They were also known for their seafaring skills.

However, it is also possible that the Uluburun ship was owned and operated by a group of merchants from another civilization, such as the Egyptians or the Phoenicians. The evidence is not conclusive, and the identity of the owners and operators of the Uluburun ship remains a mystery.

Where did the crew of the Uluburun shipwreck originate?

While it is inferred from the personal possessions found on board that the crew and ship were either from Canaan or Cyprus, certain personal items seem to indicate that two crew members were Mycenaean. Several weights were discovered in the wreckage, and considering merchants traditionally owned a personal set of weights, it may be argued that the seemingly out of place Mycenaeans were travelling merchants. However, the lack of any Aegean weights might indicate that the Mycenaeans on board were not merchants, and therefore were most likely crewmembers. The stone sceptre head found, whose closest parallel was discovered in modern day Bulgaria, helps to connect this ship and its trading endeavours to the lands north of Greece. Additionally, the tin ore found, mined in Afghanistan, indicates trading relationships between the eastern Mediterranean world and Asian tribes almost as far east as the Himalayas. Therefore, the excavated artifacts prove that the Levantine coast and Cyprus would have served as centres of major international trade, connecting not only the two major powers of the Hittite and Egyptian Empire, but also the Mycenaean culture and those tribes as far inland as Afghanistan.

What was the Uluburun ship's cargo?

Glass ingots from the Uluburun

The Uluburun ship was a merchant vessel that was carrying at least 20 tonnes of cargo on its final voyage. Just as a matter of interest, the value of the bulk cargo alone has been calculated from prices in contemporary times, to be enough to feed a town as large as Ugarit for a year.

In the hold was 10 tonnes of Cypriot copper in the form of 348 ox hide ingots together with 1 tonne of tin ingots, coincidentally (or not) the exact proportion of copper to tin required to make good bronze.

150 Canaanite jars contained half a tonne of terebinth resin and oil. Terebinth resin was used to help prevent wine turning to vinegar and for medicinal purposes.

350 kg of blue glass ingots from Egypt and an unknown quantity of fabric of which only a few red and purple threads remain.

A consignment of elephant and hippopotamus tusks and carved ivories.

Blackwood or ebony, one of the most expensive woods in the world, from the Sudan.

Weapons, arrowheads, spearheads, maces, daggers, lugged shaft-hole axe. Four bronze swords (Canaanite, Mycenaean, and central Mediterranean types). One sword was of a type from Sicily or southern Italy. Its presence on the Uluburun indicates the early entry of the central Mediterranean into the established eastern Mediterranean networks.

A large number of tools included sickles, awls, drill bits, a saw, a pair of tongs, chisels, axes, a ploughshare, whetstones, and adzes.

Miscellaneous cargo included: myrrh and frankincense, ostrich eggs, gold, silver and tin objects, a gold masked bronze goddess, several Cypriot storage pithoi, some containing jugs, bowls and lamps, including Base Ring II Ware, White Shaved Ware, White Slip Ware and Bucchero Ware, Aegean pots, mainly stirrup jars, ritual vessels made from faience, thousands of beads, Baltic amber, a stone ceremonial axe from the Danube, musical instruments including a tortoiseshell lyre, bronze finger cymbals and an ivory trumpet, basketry, matting, rope, food plants such as olives, grapes, almond, figs, pomegranates, coriander, capers and safflower, orpiment used for tanning or dyeing, murex opercula used as a medicinal product (murex trunculus is the shell used to make purple dye), bone gaming pieces and fishing gear.

Finally, the tools of the merchant's trade. There were 149 balance weights divided into sets to correspond to the different standards prevalent in the eastern Mediterranean and Levant, cylinder seals and scarabs, including one bearing the cartouche of queen Nefertiti, and a small folding writing board (a diptych) stored in a pithoi with a pristine wax surface ready to record a transaction.

Where did the Uluburun cargo come from?

Copper ingots on the Uluburun

Although the origins of the items found at the Uluburun shipwreck covered a geographical range as far west as Romania and as far east as Afghanistan, as far north as the Baltic, down to the central Mediterranean, most of the trade goods were traced back to the Levantine coast, which was contested by the Egyptian and Hittite Empires during this time. Plenty of the smaller items could have been picked up at most of the trading posts around the eastern Mediterranean. The clay used in the Canaanite jars came from the Carmel range, arguing for a stop in that vicinity. The bulk of the goods on board, the copper ingots, originated from the island of Cyprus, specifically, a mine near Apliki, which at this time had a Mycenaean presence but was independent of any large empire. Other commodities included Egyptian ebony, 2,000 pounds of terebinth resin stored in Canaanite jars, and almost 200 coloured disc-shaped glass ingots from Egypt.

In 2022, Michael Frachetti, professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, revealed the findings following tin isotope analysis of the tin ingots found on the Uluburun. One-third of the tin aboard the Uluburun shipwreck was sourced from the Musiston mine in Uzbekistan. The remaining two-thirds of the tin derived from the Kestel mine in ancient Anatolia.

When we look at the sources of the various foods and other products found on the Uluburun, the story really starts to fascinate and also gives an insight into how the Spice Road worked.

The pomegranate originated in Iran and Afghanistan. The ones on the Uluburun probably joined the Spice Road camel train that was already carrying some of the tin cargo to Haifa.

Almonds are thought to have originated in China and Central Asia and are known to have been eaten by merchants as they travelled down the Spice Road.

Figs, olives and grapes, were grown in the Near East so could easily have been grown fairly locally to any Levantine port.

Coriander originated in Italy. By the 2nd millennium BC it's cultivation had spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean, as had the growing of capers. Both could have been available on the local market in any of the Levantine ports of call.

The safflower was probably grown in Turkey and the orpiment was probably mined in Turkey.

The elephant and hippopotamus tusks and ostrich eggs were carried from Egypt.

Finally, researchers have looked at the diptych and determined that the wood from which the frame was manufactured, was from the Amanus mountains near the Syrian coast. Was the merchant from what is now Syria?

What was the purpose of the cargo?

Weapons forund on the Uluburun

The purpose of the Uluburun ship's cargo is unknown, but there are a few possible explanations.

One possibility is that the cargo was intended for trade. The Uluburun ship was carrying a large and varied cargo, including copper, tin, gold jewellery, and ivory carvings. These goods were all valuable commodities that could have been traded for other goods or for profit.

The size and value of the cargo and the skills required to work the raw materials, such as the glass and ivory, suggests that the ship's owners were targeting a palatial market.

Another possibility is that some of the cargo was intended as a gift. The Uluburun ship was carrying luxury goods often exchanged between ruling elites.

The excavator of the shipwreck, George F. Bass, believes that the ship was on a royal voyage on behalf of the King of Alashiya, the name of a place which is often attributed to Cyprus, as the enormous amounts of copper found in the shipwreck cannot possibly be part of a shipment by a private trader, and only a king could assemble a quantity of metal this great.

This supposition, intriguingly, may be born out by some of the texts in the Armana documents. The Amarna Letters is a group of correspondence in the shape of clay tablets, between the rulers of the Ancient Near East and Egypt, all written between about 1360 and 1332 BC. Mentioned in these letters is the kingdom of Alashiya, often connected to Cyprus.

Here, the king of Alashiya called the king of Egypt his brother, indicating cordial and strong relations between the two cultures. Eight Amarna texts, sent to Egypt from Alashiya, attest to this relationship, specifically mentioning gift exchange with Egypt. The amount of copper on the Uluburun ship comes to about 320 talents worth of copper, which, according to the Amarna Letters, was the average for one shipment of copper from Alashiya to the Egyptian treasury as part of the gift exchange.

The Uluburun ship yielded the world�s largest Bronze Age collection of raw metals ever found � enough copper and tin to produce 11 metric tons of bronze of the highest quality. Had it not been lost to sea, that metal would have been enough to outfit a force of almost 5,000 Bronze Age soldiers with swords.

Where did the Uluburun ship come from and where was it going?

The Uluburun ship was most likely sailing from a Levantine port, carrying Canaanite merchants to a Mycenaean emporium, when it sank off the coast of southern Turkey around 1305 BC.

The evidence for this comes from the cargo of the ship, which includes a wide variety of goods from different parts of the Mediterranean and, as it transpires, further afield.

The research undertaken by Frachetti indicated that the tin from the Musiston mine in Central Asia's Uzbekistan travelled more than 3,200 kilometres to the Phoenician port of Tel Shikmona, now Haifa, where the ill-fated ship loaded part of its cargo of tin and probably the gold jewellery, Egyptian ivory, and other luxury goods from North Africa. Tel Shikmona was itself a trading centre attracting merchants from all over the eastern Mediterranean.

The pottery from the Uluburun shipwreck also provides clues about the ship's origins and destination. Most of the pottery is of Cypriot origin, which suggests that the ship may have stopped over at Cyprus, perhaps the Phoenician port of Kition. There is also a significant amount of Mycenaean pottery, which suggests that the ship had also been to a Mycenaean port, possible Knossos on the island of Crete. The tin from the Taurus mountains in Anatolia was probably loaded at one of the ports on the coast of southern Turkey. This area was a major crossroads of trade in the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean. Ships from all over the region would have passed through this area, and it is likely that the Uluburun ship was one of them. The exact route that the Uluburun ship was taking is unknown but may have been Tel Shikmona, Kition, Knossos, one of the many trading centres on the southern coast of Anatolia. At each of the ports of call, goods would have been exchanged, increasing the value of the cargo at each stop. The final destination of the Uluburun wreck may never be known, if indeed there was a final destination as such. It is likely that, now heavily loaded, the next port of call would have access to a major bronze producing centre where the copper and tin would have been offloaded and exchanged for more luxury goods prior to a return to its home port or a continuation of a grand tour of the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean Sea.

Why did the Uluburun ship sink

The exact cause of the Uluburun shipwreck is unknown, but there are a few possible explanations.

One possibility is that the ship sank due to a storm. The Uluburun ship was found in a relatively shallow area of water, which suggests that it may have foundered during a storm whilst trying to find shelter. There has been speculation that the heavily laden ship was caught broadside on by a gust of wind over the Kas hills, a known phenomenon in the area.

The Political Situation in the Levant between 1335 and 1305 BC

Between 1550 and 1100 BC, much of the Levant was contested between Egypt and the Hittites. At the time the Uluburun ship founded though, the whole of the Levant was controlled by Egypt. The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt was the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty spanned the period from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. Egypt had long been a customer for luxury goods from all over the known world. The Phoenicians had been trading with Egypt since at least 3000 BC. Today we would say that Egypt enjoyed much favoured nation status with the city states of Phoenicia.

We should not ignore the Assyrian Empire (as Egypt found to its cost hundreds of years later) that was expanding and becoming the dominant power of northern Mesopotamia. Ashur-uballit I, who reigned between c. 1363 and c. 1328 BC, was the first king of the Middle Assyrian Empire. He and his successors depended on luxury goods to maintain their status. The Assyrian Empire became a bottomless pit for luxury goods from all over the Mediterranean, a pit the Phoenicians in the Lebanon were more than happy to fill, for a price. Perhaps the ultimate destination, now packed with a high value cargo, was Byblos or Tyre, both of which cities had direct trading links with northern Mesopotamia and the Assyrians.

Ongoing Research

The cargo of the Uluburun shipwreck has been the subject of extensive research. This research has revealed a great deal about the trade networks of the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean. The copper and tin ingots from the Uluburun shipwreck indicate that the ship was involved in the long-distance trade of these metals. The gold jewellery from the Uluburun shipwreck indicates that the ship was also involved in the trade of luxury goods.

The Uluburun shipwreck is a major archaeological discovery that has shed new light on the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean. The research on the Uluburun shipwreck is ongoing, and it is likely to continue to yield new insights into this fascinating period of history.

Where is the Uluburun shipwreck now?

The Uluburun wreck and its cargo are on display at the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Bodrum, Turkey.

The exhibition at the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology is divided into two parts. The first part tells the story of the discovery of the wreck and the excavation process. The second part displays the artifacts from the wreck, including the copper ingots, tin ingots, ivory vessels, and glass beads.

The exhibition is a fascinating journey back in time to the Late Bronze Age. It provides a glimpse into the world of ancient trade and the wealth and sophistication of the civilizations that once thrived in the Mediterranean region.

Renovations began in 2018 to improve the museum's facilities and to make it more accessible to visitors. The new museum will have a larger exhibition space, a new auditorium, and a new research centre.

The exact opening date of the museum has not yet been announced. It is expected to open sometime in 2024. Check before you go.

References

The Uluburun Shipwreck: An Overview by Cemal Pulak, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology in 1998.

The Uluburun Late Bronze Age Shipwreck by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, published on their website.

Mapping across time and space Project #3 Uluburun Shipwreck by the Brown University Archaeology Department, published on their website.

The Uluburun Shipwreck: A Bronze Age Cargo of Trading Goods by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, published on their website.

The Uluburun Shipwreck: A Major Archaeological Discovery by the World History Encyclopaedia, published online.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uluburun_shipwreck

https://blogs.brown.edu/arch-0420-2014-spring-s01/category/weekly-post/

https://source.wustl.edu/2022/11/findings-from-2000-year-old-uluburun-shipwreck-reveal-complex-trade-network/

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

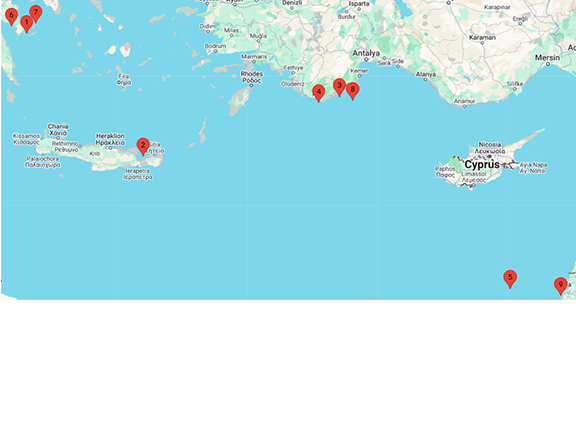

1: Dokos Shipwreck 2200 BC

1: Dokos Shipwreck 2200 BC 2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC

2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC 3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC

3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC 5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck

5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck 6: Point Iria Shipwreck c 1200 BC

6: Point Iria Shipwreck c 1200 BC 7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC

7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC 8: Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC

8: Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC 9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast

9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast 10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques

10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques 11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary

11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary