Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

Late Bronze Age shipwreck at Point Iria c 1200 BC

The remains of the Point Iria shipwreck are important for being one of the rarest and most important assemblages of pottery found in the Greek waters.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-30 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 3,527 times

Pseudomouth Amphorae - Point Iria wreck 1200 BC

Where was the Point Iria shipwreck found?

Point Iria is on the southern coast of Argolis, in the Argolid Gulf in the Aegean Sea. The wreck off Point Iria was found in 1962 when Nikos Tsouchlos located a shipwrecked cargo of clay vessels, 10 metres from the rocky shore and at a depth of 12 to 27 meters.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

About the Point Iria wreck site

The discovery of cargo from other wrecks nearby indicates that Point Iria was a dangerous part of the Argolid gulf. It is mentioned in the Iliad as Point Strouthous, which is one of the places from where ships departed to take part in the Trojan War.

Who excavated the Point Iria shipwreck?

The first reconnaissance surveys were carried out at the wreck site in the years 1971, 1974 and 1990. This was followed by the systematic survey, which was carried out by the Institute of Marine Archaeological Research (IENEA), in four continuous excavation periods, from 1991 to 1994. The project was mainly financed by the A. G. Leventis Foundation and the Institute for Aegean Prehistory (INSTAP). In the 1990s, it was the second large-scale research project of the IENEA in the Aegean, after the investigation of the Proto-Helladic shipwreck on the island of Dokos.

In May 1974, Messrs. Charalambos Kritzas, Nikos Tsouchlos and Peter Throckmorton dived in the area of the wreck and filmed the seabed, as part of a program by Bruno Vailati, with the theme "Men of the Sea".

When did the Point Iria wreck sink?

The date of the wreck, the late or end of the 13th century BC, has been determined by detailed examination of the styles of pottery found at the wreck site.

How was the Point Iria ship built and what were its dimensions?

Artists impression of Point Iria ship

From the direct archaeological evidence we have to date regarding Late Bronze Age shipbuilding from the wrecks of Uluburun and Chelidonia Akra, as well as the indirect evidence from effigies and iconography, it has been generally accepted that the main method of shipbuilding, at least from the 14th century BC onwards, was that of the "shell first" construction of the ship. The planking was laid and sewn together then joined with mortice and tenon joints. The timbers that made up the frame were added last. Even these early ships had hulls, counter-hulls, decking of planks connected with wedges and pins, spars and handrails. This method proved so effective that it remained in use in the Mediterranean for more than 15 centuries. We can assume that the Cape Iria ship was a rather small merchant ship, no longer than 10 metres, built with the "shell first" method. As a means of propulsion, it would have had a square sail.

Who were the people who owned and operated the Point Iria ship?

Regarding the "nationality" of the ship, three possibilities emerge from the study of its cargo. It may have been Cypriot, Creto-Mycenaean or Mycenaean. Nevertheless, the multinational character of the ship and its crew cannot be ruled out, which has been confirmed by other Late Bronze Age wrecks that have been excavated.

What was the cargo on the Point Iria shipwreck?

Clay vessels

The cargo consisted of clay vessels of mixed origin, as is the case with most ancient shipwrecks. 25 of these, the bulk of the cargo, were preserved. Of particular interest is the group of eight tall, coarse, false-mouthed amphorae of the well-known Aegean type. Seven are unadorned, while the eighth bears written decoration consisting of a spiral on the disc of the pseudostoma and two bands below the shoulder. From their general appearance, their oval shape and the parallels found in mainland Greece and Crete, they date to the end of the 13th century. and they constitute the second largest set of "sea" pseudomouth amphorae known in the Mediterranean to this day, after that of the Uluburun wreck, which is about a century earlier.

One triangular stone anchor with three holes, weighing 25 kg, can be attached to the wreck.

Also found in the vicinity of the wreck site were three stone anchors of the composite type with the characteristic 3 holes, one at the top for the mooring rope and two at the base for the wooden nails, plus several rounded stones, probably from the ballast of the ship and some organic materials probably used to pack the cargo.

Where did the Point Iria cargo come from?

The clay vessels came from three regions of the Eastern Mediterranean: Cyprus (5 pithois and 3 spouts), Crete (8 false-mouthed amphorae) and the Argolis (3 pithamphores, 2 scyphos, 1 scyphokrater, 1 amphora, and two partially preserved cooking utensils).

The eight small mouthed amphorae came from the region of central Crete, confirmed by the laboratory analyses of the clay.

Some of the pottery was examined by Peter Day, and consisted of four pithoi, two jugs, a smaller juglet, and two basins, all of which have parallels in Cyprus. The ceramic collection of Iria is a valuable tangible testimony of the maritime transit trade in the Eastern Mediterranean region at the very end of the 13th century BC.

What was the purpose of the cargo?

The remains from the cargo look like they are part of an everyday trading expedition, and were not a special shipment. The Point Iria ship was just one of many small general trading ships plying the area at the end of the 12th century BC.

Where was the Point Iria shipwreck cargo going?

In all probability, the Point Iria ship's cargo was destined for Mycenaean ports in the Argaric Gulf.

Where did the Point Iria ship come from and where was it going?

The cargo from this shipwreck has helped determine this ship's last voyage. It departed from the south coast of Cyprus after loading the Cypriot pythoi, and then moved westwards towards Crete, where it took on some local stirrup jars. From there, it moved further west and perhaps stopped at some Mycenaean harbours before reaching the Gulf of Argos.

Why did the Point Iria ship sink?

Nobody knows for sure but, in all probability, the ship sank in a storm.

Political situation at the time

The Point Iria ship sank during a particularly unstable period. This was the time of the so called 'Sea People' who seemed to appear and disappear like wraiths, cause massive destruction and eventually the collapse of civilisations in the Levant and eastern Mediterranean. The half century between c.?1200 and 1150 BC saw the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Kassites in Babylonia, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and the Levant, and the New Kingdom of Egypt, as well as the destruction of Ugarit and the Amorite states in the Levant, the fragmentation of the Luwian states of western Anatolia, and a period of chaos in Canaan. The period after 1200 BC is often known as the 'Greek Dark ages'.

In addition to the invasions of the Sea Peoples, various explanations for the collapse have been proposed, including climatic changes causing a period of prolonged droughts or the effects of volcanic eruptions, a lack of copper and tin such that the elites were not able to maintain their lifestyles, effects of the spread of iron metallurgy, developments in military weapons and tactics, and a variety of failures of political, social and economic systems, but none has achieved consensus. More than one of these factors probably played a part.

Where is the Point Iria shipwreck now?

The findings from the Point Iria shipwreck are permanently exhibited at the Spetses Museum.

References

Arif, R. Four Late Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean and Aegean, and Their Connections to Cyprus (2016)

Phelps, W., Lolos, Y., & Vichos, Y. (Eds.). (1999). The Point Iria wreck: Interconnections in the Mediterranean, ca. 1200 BC. Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology.

Lolos, Y. G. (1995). The cargo of pottery from the Point Iria wreck. In Phelps, W., Lolos, Y., & Vichos, Y. (Eds.), The Point Iria wreck: Interconnections in the Mediterranean, ca. 1200 BC (pp. 105-180). Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology.

Day, P. M. (1995). Petrographic analysis of ceramics from the shipwreck at Point Iria. In Phelps, W., Lolos, Y., & Vichos, Y. (Eds.), The Point Iria wreck: Interconnections in the Mediterranean, ca. 1200 BC (pp. 181-192). Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology.

Vichos, Y. (1999). The Point Iria Wreck. In Phelps, W., Lolos, Y., & Vichos, Y. (Eds.), The Point Iria wreck: Interconnections in the Mediterranean, ca. 1200 BC (pp. 11-36). Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology.

Master Seafarers: The Phoenicians and the Greeks (Periplus, 2004), 105-111.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

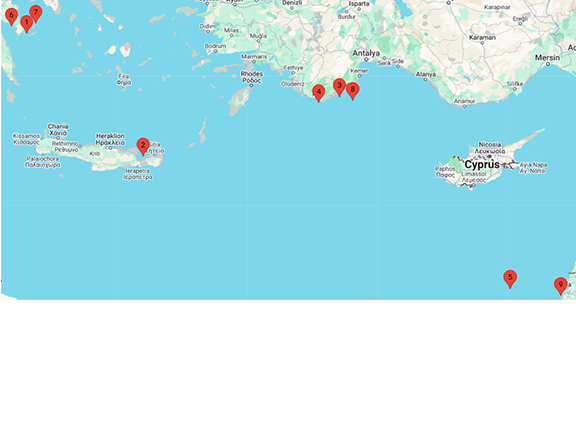

1: Dokos Shipwreck 2200 BC

1: Dokos Shipwreck 2200 BC 2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC

2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC 3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC

3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC 4: Uluburun Shipwreck 1335 - 1305 BC

4: Uluburun Shipwreck 1335 - 1305 BC 5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck

5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck 7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC

7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC 8: Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC

8: Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC 9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast

9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast 10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques

10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques 11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary

11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary