Civilisations that Collapsed

The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

Did the Trojan War happen? If so, when did the Trojan War occur? Was the Trojan War and the battle of Troy just one element in the general collapse of the bronze age civilisations in the Middle East?

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-19 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 9,080 times

Trojan War and the Siege of Troy

Was the Trojan War a Real War

The Trojan War, a legendary clash between Greeks and Trojans, has captivated audiences for millennia. Immortalized in Homer's epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, the war has transcended its origins as an oral tradition to become a cornerstone of Western literature. However, separating historical reality from poetic embellishment remains a central challenge for scholars. This article looks into the archaeological evidence associated with Troy, analyses potential motivations for the conflict, and explores the Trojan War's enduring cultural legacy.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Unearthing Troy: Archaeological Evidence and the Question of Historicity

The search for physical evidence of Troy begins with the city itself. Homer situates Troy in northwestern Anatolia (modern-day Turkiye).

What is Troy called Today?

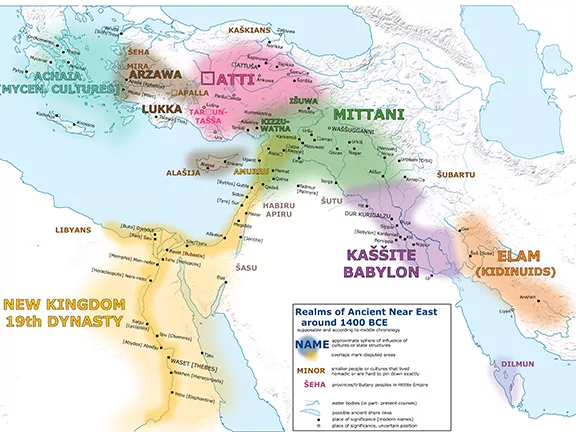

Archaeological excavations on the mound of Hisarlik, 4.5 kilometres south of Canakkale (Galipoli), Turkiye, have revealed a fortified settlement with successive layers representing distinct periods of habitation, dating back as far as 3000 BC. Notably, stratum Troy VIIa exhibits significant signs of destruction by fire around 1190 - 1180 BC, a timeframe that aligns with the traditional narrative of the Trojan War, between 1250 and 1175 BC. The Hittites knew Troy by the name Wilusa and the Greeks called it Ilion (hence Homer's Iliad). To complicate matters further, in the middle of the second millennium BC, Wilusa appears to have been part of a region called Assuwa.

However, the archaeological picture is not without its ambiguities. The epic scale of the siege depicted in the Iliad, with its decade-long duration and thousands of Greek ships, might be an exaggeration. The conflict at Wilusa could have been a smaller, regional one, its significance amplified through oral traditions and eventually, epic poetry.

Physical History of Troy

The history of Troy, determined by excavations, analysis of artefacts found and references to the city in Hittite texts is fairly typical of the history of a city state that found itself on the boundaries between two great powers, in this case the Mycenaeans and the Hittites, and was coveted by both. For that reason, it is worth taking a closer look at this city whose name has achieved mythical status.

When was Troy founded?

Excavations as late as 2014 AD, reveal a city that dates back to between 3600 and 3500 BC. The fortifications surrounding this city were the most elaborate in northwest Anatolia at the time.

Troy between 3000 and 2550 BC

By 3000 BC, the city, now on the edge of a shallow lagoon, had a citadel about one hectare in extent and massive limestone fortifications. Some of the houses had a rectangular hall that was surrounded by four columns, fronted by an open, two-columned portico, and had a central, open hearth that vented though an oculus in the roof, a design known as a megaron that was common in Mycenaean palace complexes. The occupants of this city appear to have come from the neighbouring towns of Kumtepe and Gulpinar that already had economic and cultural ties with islands in the eastern Aegean, Thessaly in northeastern Greece and southeastern Europe. This city lasted until 2550 BC, when it was destroyed by fire.

Troy between 2550 and 2300 BC

Fifty years later, the inhabitants had restored their city to twice its size and were producing wheel made pottery. Their trading contacts brought them amber from the Baltic regions, carnelian from India and lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. The city was destroyed about 2300 BC for unknown reasons.

Troy between 2300 and 1750 BC

There is little archaeological evidence spanning the years 2300 BC to 1750 BC except to show that the site was occupied, and towards 1750 BC, there was contact with the Minoans.

Troy between 1750 and 1300 BC

The city that emerges from the excavations about 1750 BC was destined to last until about 1300 BC. It had a citadel and megaron style buildings surrounded by a massive limestone wall that is still visible today. The architectural styles show both Mycenaean and Hittite influence. The citadel, perched on the hill, overlooked the Trojan plain and the sea beyond, had no less than five imposing gates. Below the citadel, the lower city, only discovered in 2013 AD, sprawled across the plain. Pottery found at the site show commercial contacts with Crete, Mycenae, Cyprus, and the Levant. Notably, there are no Hittite artifacts in this level. The city was probably destroyed by an earthquake around 1300 BC.

Troy between 1300 and 1180 BC

Above the earthquake destruction layers, there is evidence of a rebuilt city. It was built from the same materials as the previous city and re-used some surviving structures such as the citadel wall. The material culture of the builders and residents was the same as that of the previous occupants of the city. The area of the new city occupied by houses, below the citadel, was greater than that of the residential area of the previous city. Crucially there is evidence that foreign imports declined rather than increased as they would have had the new owners been the Mycenaeans. This city was destroyed around 1180 BC, roughly contemporary with the Late Bronze Age collapse but before the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces (about 1050 BC). The destruction layer shows evidence of enemy attack. Arrowheads were embedded in walls and bodies were found lying in the street. In the lower city, there were signs of burning and the skeleton of a teenage girl, half buried with her feet burned by fire.

Troy between 1180 and 1050 BC

Again, the city was rebuilt. The residents once more appear to be a continuation of the previous owners. As far as material culture goes, a fresh style of pottery appears in this layer called Anatolian Grey Ware. There have also been some finds of Mycenaean style pottery. This version of Troy met its end in 1050 BC after a violent earthquake.

So much for the physical history of Troy. We can now turn to what written archives tell us about the city and its relationship with Mycenae and Hattusa. Most of this information originates in texts found at Hattusa and only covers the period after 1400 BC.

Political History of Troy

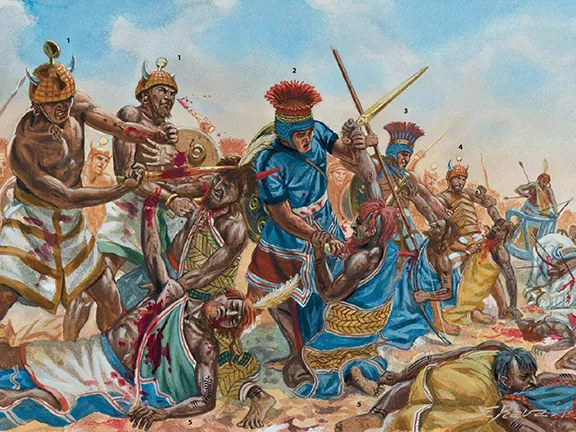

The Assuwa Revolt

Assuwa was a confederation of twenty-two states in western Anatolia around 1430 BC. The confederation was formed to oppose the Hittite Empire and is mentioned in six Hittite texts of the time. The most detailed account of the revolt is from the Annals of Tudhaliya I/II;

'But when I turned back to Hattusa, then against me these lands declared war: [-]lugga (probably the Lukka lands), Kispuwa, Unaliya, [-], Dura, Halluwa, Huwallusiya, Karakisa, Dunda, Adadura, Parista, [ ], [-]waa, Warsiya (probably Troy), Kuruppiya, [-]luissa, Alatra, Mount Pahurina, Pasuhalta, [-], Wilusiya, Taruisa. [These lands] with their warriors assembled themselves ......... and drew up their army opposite me.'

Suspected Mycenaean involvement in the revolt appears to have been confirmed in 1991 AD when a road worker uncovered a sword near the Hittite capital of Hattusa. The sword was of a Mycenaean design and handily inscribed with a text in Akkadian that, when translated, read; 'As Duthaliya the Great King shattered the Assuwa country, he dedicated these swords to the storm-god, his lord.' The sword could have been taken from an Assuwan soldier, engraved with the text, and then left as an offering to the Hittite storm-god.

Alaksandu Treaty

In 1280 BC, from a text known as the Alaksandu Treaty, we learn that Wilusa has a mutual defence treaty with the Hittites. The Treaty was signed by Alaksandu of Wilusa and the Hittite king, Muwatalli II. Part of the pact reads.

'And as I, My Majesty, protected you, Alaksandu, in good will because of the word of your father, and came to your aid, and killed your enemy for you, later in the future my sons and my grandsons will certainly protect your descendants for you, to the first and second generation. If some enemy arises for you, I will not abandon you, just as I have not now abandoned you. I will kill your enemy for you.'

Alaksandu was expected to provide the Hittites with information about any anti-Hittite activity and with soldiers in the event of conflict.

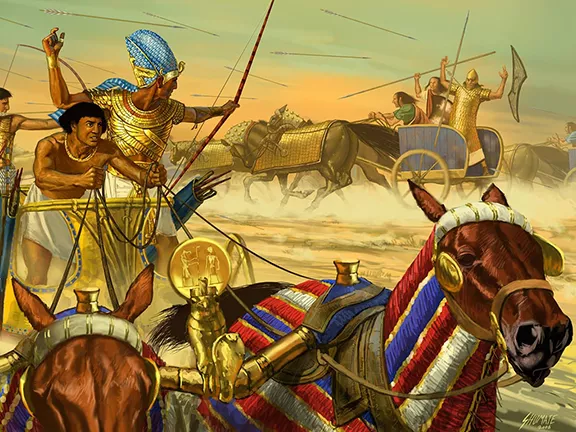

About 1274 BC, the pact was tested when the Hittite army with a number of allies, including troops from Wilusa, faced an Egyptian army at the Battle of Kadesh.

Manapa-Tarhunta letter

Wilusa next appears in a text known as the Manapa-Tarhunta letter, written about 1295 BC. The letter was written by Manapa-Tarhunta, king of the Seha River Land, a Hittite vassal city state in western Anatolia, south of Wilusa and sent to the Hittite king, probably Muwatalli II who ruled between 1295 and 1272 BC. The letter informs us that an anti-Hittite rebel named Piyamaradu had attacked the Seha River Land. The section of the letter that concerns us here reports that Hittite troops had arrived in Seha, established order, and then moved on to Wilusa. We can assume from the Milawata letter (below) that the Hittites regained control of Wilusa and retained it until about 1240 BC.

Piyamaradu was a complex character sometimes described as 'a rebellious Hittite dignitary,' who for 35 years encouraged rebellions in the Hittite vassal city states in western Anatolia. He posed a threat to three Hittite kings, Muwatalli II, Hattusili III and Tudhaliya IV, so must have been active between about 1275 BC and 1240 BC. He was trying, unsuccessfully, to reassert his rights to the throne of Arzawa, a Hittite dominated region in western Anatolia. Having been repulsed by the 'Great King' of Hatti, Piyamaradu formed an alliance with the Ahhiyawa (Mycenaeans), by marrying off his daughter, to Atpa, the Mycenaean vassal king in Miletus.

Piyamaradu was again of royal concern about 1250 BC at which time he was seeking asylum in Ahhiyawa controlled territory after fomenting an unsuccessful rebellion in Lukka. This escapade persuaded the Hittite king to write to the king of the Ahhiyawa, a letter known as the Tawagalawa letter that also mentions a disagreement over Wilusa, hence its validity here.

Tawagalawa Letter

Written about 1250 BC, the Tawagalawa letter primarily deals with the relationship between the Hittites and Ahhiyawa. However, it also mentions a disagreement over Wilusa.

The Tawagalawa letter was probably written by the Hittite king Hattusili III and was sent to an unknown king of Ahhiyawa via his brother, Tawagalawa. Tawagalawa was at the time in western Anatolia gathering together a mercenary army who were hostile to the Hittites. The letter asks for help in suppressing anti-Hittite activity in western Anatolia, in particular the activities of the rebel Piyamaradu. The king of Ahhiyawa was given three options; to extradite Piyamaradu to the Hittites, to expel him from Ahhiyawa or to offer Piyamaradu asylum on condition he does not try to initiate any further rebellions.

It is apparent from the tone that Hattusili III, if indeed he was the author of the letter, regarded the Ahhiyawa king as an equal, referring to him as 'my brother' (see the article 'Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires').

The letter goes on to refer to previous disputes over Wilusa which had now been settled amicably,

'Oh, my brother, write to him this one thing, if nothing else: '...the king of Hatti has persuaded me about the matter of the land of Wilusa concerning which he and I were hostile to one another, and we have made peace.'

And later.

'And concerning the matter (of Wilusa), about which we were hostile, (because we have made peace) what then?'

Milawata Letter

The Milawata letter was sent by Hittite king Tudhaliya IV to one of the Hittite vassal states in western Anatolia, probably the Kingdom of Mira, in about 1240 BC.

Shortly after the adventures of Piyamaradu, or right at the end of his campaigns, Wilusa had a king called Walmu and Wilusa was a Hittite vassal state. Walmu had apparently been deposed, by whom we know not, but we must strongly suspect confederates of the Mycenaeans, and had fled to another of the Hittite vassal states in western Anatolia.

The letter asks for Walmu to be returned to Hattusi so that he can be re-installed as king of Wilusa and promises that the recipient (probably the king of Mira), would retain ultimate control over the various city states in the region. The tone of the letter when referring to Ahhiyawa, i.e. the Mycenaeans, suggests that Ahhiyawa was a declining power at this time just ten years after they were considered equals.

Kings of Wilusa

Thanks to mentions in various texts, we know the name of three kings of Wilusa and approximately when they reigned.

Kukkunni (c.?1350 BC), ruled contemporaneously with Hittite king Suppiluliuma I.

Alaksandu (c.?1300 BC until after 1280 BC), ruled contemporaneously with the Hittite kings Mursili II and Muwatalli II, signing peace treaties with them.

Walmu (c.?1250 until after 1220 BC), a vassal of the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV and the state of Mira, dethroned following a possible occupation of the raids by the Ahhiyawa people. The letter from Milawata (Miletus) states that Walmu sought political asylum from Tarkasnawa, his suzerain in the kingdom of Mira. It seems that King Tudhaliya IV urged Tarkasnawa to send Walmu to the Hittite Kingdom so that he could reinstate him on the throne and return to the vassal position of both as he had been in the past.

Beyond Helen: Exploring Alternative Motives for Conflict

We have explored the physical and written evidence dealing with the history of Troy. We can now turn our attention to the legend.

Homer's Iliad

The Iliad attributes the Trojan War to the abduction of Helen, wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta, by Paris, a Trojan prince. While this serves as a powerful narrative device, historical realities might have been more complex. Here are some alternative motives scholars have proposed:

Trade Disputes: Controlling vital trade routes and resources in the Aegean Sea could have been a significant factor. Troy's strategic location made it a crucial point for commerce, and the Mycenaeans, the dominant Greek civilization of the era, might have sought to exert greater control.

Geopolitical Rivalry: The Mycenaeans, a powerful Bronze Age civilization centred on mainland Greece, could have viewed Troy, potentially a major Anatolian city-state, as a rival. Conflict might have been a natural consequence of this competition for power and influence.

Endemic Warfare in the Bronze Age: Raiding and warfare were commonplace practices in the Bronze Age. The Trojan War might have been part of a larger pattern of conflict between the Mycenaeans and neighbouring powers.

The Mycenaean Connection: Heroes, Warfare, and the Power of Oral Traditions

The Iliad introduces us to a pantheon of Greek heroes like Achilles, Ajax, Odysseus, Heracles, Nestor, and Agamemnon. While their larger-than-life portrayals may be poetic license, these figures might have some basis in reality:

Mycenaean Warrior Culture: The Mycenaeans were a warrior society, and the Iliad likely reflects their military practices and social hierarchy. The heroes could represent real Mycenaean leaders or archetypes of the warrior class.

Evolution of Oral Traditions: The stories of the Trojan War were likely passed down through oral traditions for centuries before being written down. These traditions might have incorporated and embellished the deeds of real Mycenaean leaders.

Deification and Mythologization: Some scholars believe that certain heroes might have been deified or elevated to mythical status over time. Their real accomplishments might have been exaggerated and intertwined with supernatural elements.

The Trojan Horse: Metaphor or Misinterpretation?

The Trojan Horse, a giant hollow horse filled with Greek soldiers that infiltrated Troy, is one of the most enduring images of the war. However, there is no archaeological evidence to support its literal existence. Wooden structures would not survive for millennia.

The Trojan Horse could be interpreted in several ways:

A Clever Ruse: Perhaps the story represents a real tactic, such as a surprise attack hidden within a seemingly harmless object.

A Battering Ram Disguised as a Horse: Some scholars suggest the Trojan Horse might be a metaphor for a battering ram disguised as a horse to breach the city walls.

Symbolic Representation of Deception: The horse could represent the Greeks' use of cunning and trickery to overcome the Trojans' defences.

When did the Trojan War Happen

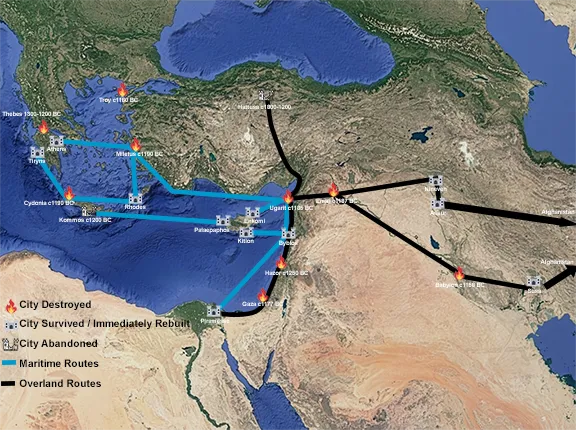

The date favoured by many scholars is 1250 BC, mainly due to the evidence of destruction in the Troy VIIa stratum and the fact that around that time or slightly later, other bronze age cities were being destroyed. They also consider the Tawagalawa letter written about 1250 BC, which refers to a now settled dispute between the Hittites and Mycenaeans over Wilusa.

But could the Trojan War be set some two hundred years before then, as part of the Assuwa rebellion? There is to date, no archaeological evidence of conflict in the city that existed between 1750 and 1300 BC, to suggest there was a major attack on the city of Troy about 1430 BC, by Mycenaeans or anybody else.

Despite the lack of physical evidence, there are pointers that indicate the war did happen somewhat earlier than 1250 BC. In his Iliad, Homer describes Ajax's shield as a tower shield and some of the swords carried by the heroes as 'silver studded' swords. The tower shield went out of use long before the 13th century BC as had the expensive silver studded sword.

This author's opinion is that Homer drafted a good story based on events that occurred over a lengthy period of time. He intended to create a memorable story of heroes, a band of brothers who had been ready to come to the aid of ancient Greece throughout eternity. To give them a timeless legitimacy, he used imagery from frescoes of battles fought long ago, possibly even the famous fresco from Akrotiri on the island of Thera, to inspire his descriptions of their weaponry.

Beyond the War: The Legacy of the Trojan War

Even if the details of the conflict are uncertain, the Trojan War left an undeniable mark on history and culture:

Foundational Myth for the Greeks: The Trojan War became a cornerstone of Greek identity, shaping their understanding of heroism, warfare, and their relationship with the gods.

Influence on Western Literature and Art: The Iliad and Odyssey have inspired countless writers and artists for centuries. Themes of war, heroism, love, and betrayal continue to resonate in modern works.

A Reminder of War's Devastating Effects: While often romanticized, the Trojan War serves as a cautionary tale about the destructive nature of conflict and the human cost of war.

The Search Continues: Unravelling the Mysteries of Troy

The quest to understand the Trojan War is an ongoing process. Archaeological research at Troy continues, with each new discovery offering a piece of the puzzle. Future excavations might reveal additional details about the city's inhabitants, their military practices, and potential interactions with the Mycenaeans. Additionally, advancements in scientific analysis of artifacts could shed light on the precise dating of the various layers at Troy and potentially provide further clues about when the conflict occurred.

References

Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012). The Ahhiyawa Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 115. ISBN 978-1589832688.

Bryce, T. (2005). The Trojans and their Neighbours. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-34959-8.

Chadwick, J. "The Mycenaean World"

Cline, E.H. "The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction"

Cullen, L. "The Mycenaean World and the Late Bronze Age Aegean"

Griffin, J. "The Greeks" by Jasper Griffin

Hoffner, Beckman. Letters from the Hittite Kingdom, 2009. p. 297.

Jablonka, Peter (2011). "Troy in regional and international context". In Steadman, Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press. p. 725. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0032. Since neither inscriptions confirming the Iliad nor definite proof for a violent destruction by invaders from Greece have been discovered at Troy

Korfmann, M "Troy and the Trojan War"

Rose, Charles Brian (2013). The Archaeology of Greek and Roman Troy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76207-6.

"The Fortification Wall". Troy Excavations. 2023. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

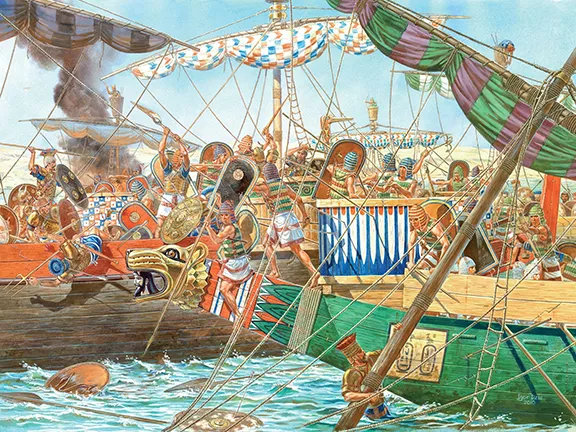

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron