Civilisations that Collapsed

The Mystery of the Bronze Age Sea Peoples

The Bronze Age sea peoples who ravaged the Middle East during the late Bronze Age were an enigma to the powers that ruled the land. Who were they and where did they come from? Did they play a part in the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations?

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-19 | Last Updated 2025-11-30 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 7,046 times

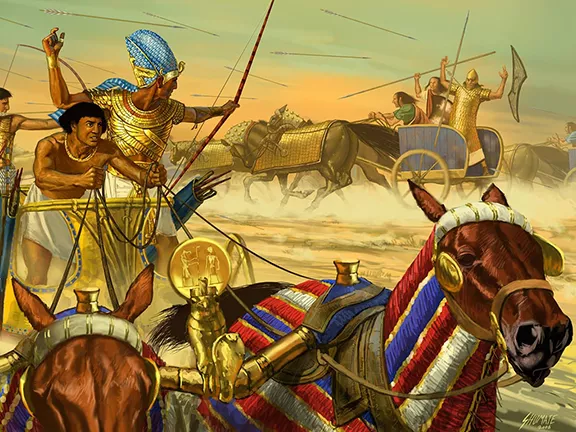

The Sea Peoples Image: Painting by Igor Dzis/Karwansary Publishers

Who Were the Sea Peoples?

By definition, the Sea Peoples originate from overseas. However, as we shall see, many, if not most, of the Sea Peoples had their feet firmly on dry land. Some have been labelled pirates, even this is hardly fair in the 12th century BC.

Piracy is as old as maritime trading, although it is unfair to call the 13th and 12th centuries BC perpetrators of sea heists pirates. Nobody as yet, ruled the waves. The very word 'pirates' implies a judgement imposed by land-based people in power presuming to declare what was legal. Fairer perhaps to describe these proto-pirates as freebooting and sometimes predatory mariners who opposed land-based authority.

Raiders from the land of Lukka

One of the earliest mention of pirates appears in an Armana letter written by the king of Alasiya (Cyprus) to Pharoah Akhenaten, sometime around 1340 BC.

Akhenaten had held in detention an envoy from the kingdom of Alasiya as a protest against Alasiyan alleged participation in pirate raids upon the Egyptian coast. The pirates had been operating in the eastern Mediterranean and along its shores from bases on Anatolia's southern coast, within the territory called Lukka in Hittite texts. Akhenaten had written to the Alasiyan king accusing him and his subjects of complicity in the raids. The accusation was indignantly denied:

'Why, my brother, do you charge me with this? I have done nothing of the kind!'

On the contrary, the writer declared, Alasiya too had been plagued by the pirates.

'These men from Lukka seize villages in my own country year after year!'

And he went on to assure the pharaoh that his own subjects would never have joined them.

In fact the pharaoh's allegations may not have been entirely without foundation, for some of the pirates taken prisoner apparently included persons of Alasiyan origin. But the Alasiyan king wanted to test the truth of this for himself.

'If men from my own country were amongst them,'

he wrote,

'return these men to me and I will do as I think appropriate.'

Even so, he really could not believe that his own subjects had committed acts of piracy:

'You simply don't know the men of my country. They would never do such a thing!'

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

New Ships and Pirates during the Reign of Rameses II

Ramesses II ruled the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1279 BC to 1213 BC. It is during his reign that a new style of ship appeared, much more suited to the needs of pirates and coastal raiding. We also receive a glimpse of the possible identities of these maritime scoundrels.

New Ships on the Horizon

During the reign of Ramesses II, or slightly earlier, a new design of ship appeared, not just over the horizon, but on pots and in engravings and inscriptions that started to appear in the Aegean.

The features that distinguished it from previous ships included a brailed rig and loose-footed square sail, a top-mounted crow's nest, and at least partial decking upon which opposing warriors are shown slinging missiles and brandishing swords. This new design was a significant step forward from the deep-hulled cargo vessels that plied the waters of the Mediterranean at this time. It could sail closer to the wind and be rowed. It had sufficient cargo space yet, with a long narrow profile, was light and fast. Unlike laden sailing craft, these galleys could be drawn up on a beach. How the separate components that made it so different came together is a fascinating story beyond the remit of this article.

Suffice to say that the final version of this warship was ideal for seaborne raiders, and it may be those people who first set sail in this new ship and that it featured in the sea battles fought by Ramesses II and Ramesses III.

Tanis Stele of Ramesses II - First Encounter with the New Ships

In 1278 BC, Ramesses II defeated a maritime force when they attempted a raid on the Egyptian coast. This may have been the first time he saw the new design of warship.

The event is recorded on the Tanis Stele of Ramesses II:

'the unruly Sherden whom no one had ever known how to combat, they came boldly sailing in their warships from the midst of the sea, none being able to withstand them. He [Ramesses] plundered them by the victories of his valiant arm, they being carried off to Egypt] as prisoners.'

He subsequently incorporated some of the Sherden prisoners into his bodyguard, where they are conspicuous by their helmets with horns with a ball projecting from the middle, their round shields and the great Naue II swords, with which they are depicted in inscriptions about the Battle of Qadesh, fought against the Hittites four years later.

The original text of the Tanis Stele shown translated above also contains a clue as to how the Egyptians viewed the Sherden and their ships. The hieroglyph used in this instance for 'warships' was a newly invented word that, when spoken, sounded like aHaw aHA (m-hry-ib pa ym), which is literally translated as 'ships of fighting in the midst of the sea.' The Sherden had turned up in a new design of fighting warship that the Egyptians had never seen before that was so different to any previous warship that a new word had to be invented.

In a letter written from Ramesses II to Hattusili III (King of the Hittites 1267 to 1237 BC), Ramesses says that he is sending a pair of ships up to the Hittites, so that his shipwrights can 'draw a copy' of it in order to build a similar ship. Did Ramesses capture a couple of ships from the invaders and send them to his new ally?

The Qadesh Inscriptions - Identifying the Sea Peoples

The Qadesh (sometimes Kadesh) inscriptions are also known as the 'Eternal Treaty' and the 'Silver Treaty.' The peace treaty between Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II and Hittite king Hattusili III was signed around 1259 BC and confirmed the following year. Each side created its own version of the agreement on silver tablets, which were subsequently replicated on other materials.

The peace treaties between Egypt and the Hittites were documented in their native tongues. The Egyptian agreement was etched in hieroglyphs upon the walls of two temples venerating Pharaoh Ramesses II in Thebes: The Ramesseum and the Amun-Re Precinct within the Karnak Temple. The Hittite document was discovered in the Hittite capital of Hattusa and is preserved on baked clay tablets unearthed from the Hittite royal palace's extensive archives.

The treaty was signed to end the two hundred years, on and off, conflict between the two powers that culminated in the Battle of Qadesh in 1274 BC. When the treaty was signed, Egypt was more concerned with incursions by other forces, by sea and land, and the Hittite Empire was being threatened by a new power on the block, Assyria. Both powers had an interest in making peace. In fact, the conflict between Egypt and the Hittites rumbled on for about fifteen years after the treaty was signed, peace only being achieved after the signing of a 'Treaty of Alliance'.

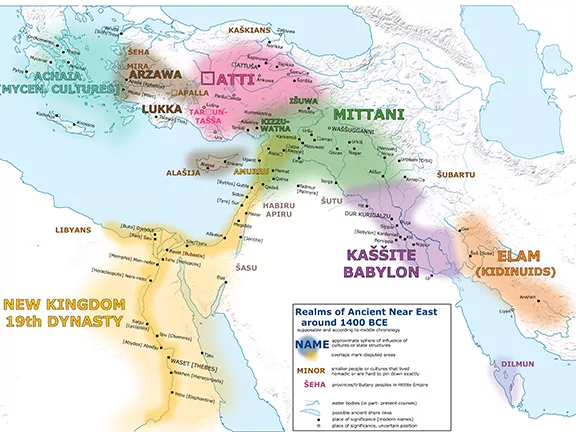

The importance of the Qadesh inscriptions, is the mention in it of three tribes; the Karkisha and the Lukka, fighting for the Hittites and the Sherden as part of Ramesses's personal bodyguard, all of whom would later be identified as part of the Sea Peoples confederacy.

Other mentions of the Lukka

In other texts, the Lukka are mentioned by the Hittites and the Mycenaeans who both consider them to be raiders who were as likely to appear from the sea as from the land. They occupied part of southern Anatolia in a region that later became called Lycia.

The Merneptah Narrative: Did the 'Sea Peoples' ally with the 'Nine Bows' Confederacy?

Pharaoh Merneptah ruled the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1213 BC to 1203 BC. During his reign, Egypt was confronted with a confederacy of enemies known to the Egyptians as the 'Nine Bows.'

In 1207 BC, Merneptah defeated the Nine Bows, led by King Mervey of Libya, in a battle at Perire in the western delta. An account of the battle, and the identity of the enemies was found in a Pharaonic inscription inscribed in three places, in the 'Great Karnak Inscription', on the 'Athribis Stele' and on the 'Cairo Column'.

The first lines of the Karnak inscription include the names of six enemy groups:

'[Beginning of the victory that his majesty achieved in the land of Libya] -i, Ekwesh, Teresh, Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Northerners coming from all lands.'

Later in the same inscription we learn that:

'The wretched, fallen chief of Libya, Meryey, son of Ded, has fallen upon the country of Tehenu with his bowmen, Sherden, Shekelesh, Ekwesh, Lukka, Teresh, Taking the best of every warrior and every man of war of his country. He has brought his wife and his children, leaders of the camp, and he has reached the western boundary in the fields of Perire'

Finally, Merneptah gives us a list of the captives he took during the battle that include the only mention within the inscription of people 'of the sea':

'[ ... Sher]den, Shekelesh, Akawasha (Ekwesh) from the foreign lands of the sea who did not have fore [skins ... ]'

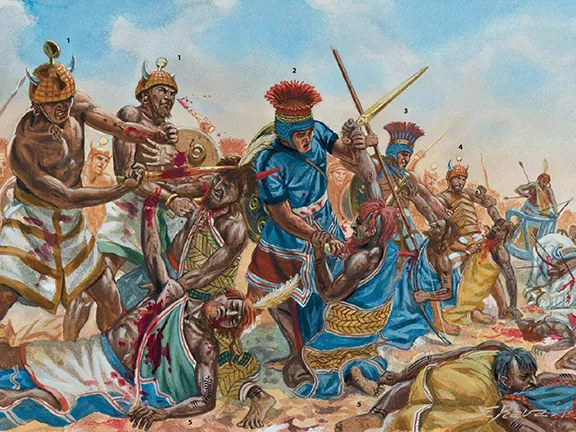

The Ramesses III Narrative: Raiders from Overseas

Pharaoh Ramesses III ruled the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1186 BC to 1155 BC. His mortuary temple at Medinet Habu records five campaigns against invading forces, three of which are considered bona fide, those in 1181, 1178 and 1175 BC.

The 1181 BC campaign: Raiders by sea and land

The 1181 BC attack was a two-pronged attack on Egypt, one force attacking from the sea, the other from on land.

In the inscription concerning the 1181 BC campaign we see the following mention of enemy forces from overseas:

'Now the northern countries, which were in their isles, were quivering in their bodies. They penetrated the channels of the Nile's mouths. Their nostrils have ceased (to function, so that) their desire is [to] breathe the breath. His majesty is gone forth like a whirlwind against them, fighting on the battlefield like a runner. The dread of him and the terror of him have entered in their bodies; (they are) capsized and overwhelmed in their places. Their hearts are taken away; their soul is flown away. Their weapons are scattered in the sea. His arrow pierces him whom he has wished among them, while the fugitive becomes one fallen into the water. His majesty is like an enraged lion, attacking his assailant with his pawns; plundering on his right hand and powerful on his left hand, like Set[h] destroying the serpent 'Evil of Character'. It is Amon-Re who has overthrown for him the lands and has crushed for him every land under his feet; King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands'

The 1178 campaign: The Battle of Djahy

The inscriptions at Medinet Habu concerning the 1178 BC campaign also mention enemy forces from foreign countries overseas:

'The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands, All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms: from Hatti, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa and Alashiya on, being cut off [i.e. destroyed] at one time. A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the land as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: 'Our plans will succeed!'

The Medinet Habu temple reliefs indicate that the Peleset and Tjekker warriors who fought in the land battle, were accompanied by women and children riding in ox carts.

Ramesses met the enemy on land at Djahy, a town close to the northern extent of Egypt's territory in the northern Levant. The enemy sacking of the Hittite city of Amurra gave Ramesses time to organise his troops as recorded at Medinet Habu thus:

'But the heart of this god, the lord of the gods, was prepared and ready to ensnare them like birds... I established my boundary in Djahi, prepared in front of them, the local princes, garrison-commanders, and Maryannu (a caste of chariot mounted hereditary warrior nobility). I caused to be prepared the rivermouth like a strong wall with warships, galleys, and skiffs. They were completely equipped both fore and aft with brave fighters carrying their weapons and infantry of all the pick of Egypt, being like roaring lions upon the mountains; chariotry with able warriors and all goodly officers whose hands were competent. Their horses quivered in all their limbs, prepared to crush the foreign countries under their hoofs.'

The Battle of Djahy was a victory for the Egyptians, as Ramesses boasts:

'The [Egyptian] charioteers were warriors [...], and all good officers, ready of hand. Their horses were quivering in their every limb, ready to crush the [foreign] countries under their feet...Those who reached my boundary, their seed is not; their heart and soul are finished forever and ever.'

The Battle of the Delta 1175 BC

Or, apparently not, because, three years later, in 1175 BC, Ramesses once again faces his enemies at the Battle of the Delta.

The Papyrus Harris I was found in a tomb near Medinet Habu. With 1,500 lines of text, it is the longest known papyrus from Egypt and is thought to have been written about 1100 BC. Parts of the papyrus refer to the campaigns during the reign of Ramesses III. The following lines contain references to people from overseas:

'I (Ramesses) slew the Denyen (D'-yn-yw-n) in their isles" and "burned" the Tjeker and Peleset,'

Once again, Ramesses boasts of his victory:

'As for those who reached my boundary, their seed is not. Their hearts and their souls are finished unto all eternity. Those who came forward together upon the sea, the full flame was in front of them at the rivermouths, and a stockade of lances surrounded them on the shore. They were dragged, overturned, and laid low upon the beach; slain and made heaps from stern to bow of their galleys, while all their things were cast upon the water.'

The Medinet Habu inscription is the first time we have an indication that the Sea Peoples may also have included land based retinues of women, children and carts.

The Ugaritic Texts

Ugarit was a city on the Mediterranean coast of what is now Syria. It was a prosperous commercial city with a port, Ras Ibn Hani, one kilometre away, on the coast itself. The merchants of Ugarit traded with other cities all over the eastern Mediterranean. In 1200 BC it was within the Hittite sphere of influence.

The Ugaritic Texts are a corpus of some 1,500 texts and fragments, all dated to the 13th and 12th centuries BC. Of these, several of the texts appear to have been written in the few years before 1180 BC when the city was destroyed.

A Letter from the last king of Ugarit to Alasya

The first is a letter from Ammurapi, the last king of Ugarit, about 1215 BC to 1180 BC, to Eshuwara, a senior functionary on Alasiya, (probably Alashiya i.e. Cyprus) in which Ammurapi informs Eshuwara, that an enemy fleet of twenty ships had been spotted at sea.

Eshuwara responded by asking Ammurapi to specify the current whereabouts of his own troops and the enemy fleet of twenty vessels. He hinted that the attacking force may have originated from Ugarit itself:

'As for the matter concerning those enemies: the people from your country and your own ships did this! And the people from your country committed these transgressions. . . . Twenty enemy ships even before they would reach the mountain shore have not stayed around but have quickly moved on, and where they have pitched camp we do not know. I am writing to inform and protect you.'

(A letter by Ammurapi to the king of Alasiya has recently been found by archaeologists that indicates that the above letter was in fact a response to an appeal for assistance by the latter.)

A Letter from Ammurapi to King Kuzi-Teshub I at Carchemish

In any case, with no help forthcoming, Ammurapi then appealed to King Kuzi-Teshub I at Carchemish, a major Hittite city in what is now southern Turkiye:

'My father, behold, the enemy's ships came (here); my cities(?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots(?) are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka?...Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.'

And the reply:

'As for what you [Ammurapi] have written to me: 'Ships of the enemy have been seen at sea!' Well, you must remain firm. Indeed for your part, where are your troops, your chariots stationed? Are they not stationed near you? No? Behind the enemy, who press upon you? Surround your towns with ramparts. Have your troops and chariots enter there, and await the enemy with great resolution!'

Suppiluliuma II versus the 'Ships of Alasiya' the first recorded sea battle

The situation is further confused by a text referring to a series of three sea battles fought by Suppiluliuma II, the last king of the Hittite Empire (1207 to 1178 BC), against the 'ships of Alasiya'. The text was written at about the same time that Ammurapi, king of the Hittite vassal city of Ugarit, was corresponding with Eshuwara on Alasiya and, incidentally, about the time Merneptah found his hands full with:

'Northerners coming from all lands': 'The ships of Alasiya met me (Suppiluliuma II) in the sea three times for battle, and I smote them; and I seized the ships and set fire to them in the sea. But when I arrived on dry land(?), the enemies from Alasiya came in multitude against me for battle. I [fought] them, and [...] me [...]...'

The text does not say, specifically, that the ships belonged to Alasiya, only that they came from Alasiya.

Suppiluliuma II won the day and the battle became the first recorded naval battle in history.

Tudhaliya II subdues Alasiya

This was not the first time that Alasiya had been in conflict with the Hittites. Suppiluliuma II's father, Tudhaliya IV (1237 to 1209 BC) had also found it necessary to invade Alasiya as originally recorded on his statue:

'I seized the king of Alashiya with his wives, his children.... All the goods, including silver and gold, and all the captured people I removed and brought home to Hattusa. I enslaved the country of Alashiya, and made it tributary on the spot.'

Why Tudhaliya and Suppiluliuma both went to the trouble of subduing Alasiya is not known for certain, especially as Suppiluliuma was already presiding over a fading Hittite Empire and being threatened from western Anatolia. It could well have been to secure a source of copper, plentiful on Alasiya. That reason is not convincing, unless Tudhaliya wanted to cut out the middleman, since Alasiya was well known in the late Bronze Age as a supplier of copper to all the empires in the Near East. In addition, Hattusi is in the middle of the Anatolian plateau, a long way from the sea and its main port Ugarit, whose merchants had been happily importing copper from Alasiya for decades. The ships used to mount Tudhaliya's and Suppiluliuma's attacks most probably belonged to the same merchants of Ugarit. There must have been a more pressing reason for punishing Alasiya, to which I will return later.

The Onomasticon of Amenemope

The Onomasticon of Amenemope (sometimes Amenemopet or Amenemipit) is an administrative document, a reference book, which gave the state of play in Egypt in about 1100 BC. It lists people and places within the Egyptian territories, who did what, who lived where, where the agricultural lands were and their produce. It is a sort of Domesday Book of Egypt. Onomasticon had been produced since the days of the Middle Kingdom. Amenemope was probably a sage and scribe who lived in Egypt between 1189 and 1077 BC.

Philistia occupied by 'Sea Peoples'

According to the scribe, four of the cities within Philistia were occupied by the Sherden, the Tjeker and the Peleset.

Philistia, the land of the Philistines, was a Pentapolis, or five cities, of Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gath, and Ekron. These cities, on the coastal plain between modern Tel Aviv and Gaza was known as Philistia, or the Land of the Philistines that the Greeks later called Palestine. According to his inscription at Medinet Habu and in the Harris Papyrus, Ramesses III relocated some of the Peleset to southern Canaan where they settled peacefully.

Who were the Sea Peoples?

During the late Bronze Age, the Sea Peoples were portrayed as the bogeymen of the Middle East, 'Don't do that or the Sea Peoples will catch you.' Every unexplained attack by sea or land was attributed to these fierce warriors, many movements of people were credited to the Sea Peoples, but is that entirely correct?

Were the 'Sea Peoples' Pirates?

We know from other texts that common or garden 'pirates' roamed the maritime trade routes, particularly the Aegean, as well as the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. Many of these 'pirates' would have been maritime traders, taking an example from their land based brethren to grab any opportunistic prize to supplement their legitimate trading activities.

Were the 'Sea Peoples' Bandits?

We can also see, from the inscriptions that some of the encounters with the Sea Peoples are, in fact, on land, with no naval involvement.

Groups of badits already existed. We know that the Habiru were an unruly bunch of mercenaries who infested the Levant.

Why populations migrate

Throughout the late Bronze Age, city-states were under attack from neighbours and the competing Great Powers. Two elements to these attacks would cause the affected populations to migrate away from their homes.

Foraging armies: The first element is as a result of how the armies moved from A to B. The troops were not issued with rations. They and any animals they possessed had to forage. In the case of large armies such as those deployed at the Battle of Qadesh, Ramesses fielded four divisions plus a troop of Canaanite mercenaries, a total of between 20,000 and 53,000 troops. His forces had something like 2,000 chariots, therefore at least 2,000 horses. Muwatalli mustered nineteen allies from the Hittite city states and kingdoms under his vassalage, all of which force marched to Qadesh from all parts of Anatolia and northern Syria. The Hittite force consisted of between 23,000 and 50,000 troops plus between 2,500 and 10,500 chariots, depending on which account you read.

In any case, the numbers of troops moving across the landscape, foraging as they went, must have been similar to herds of locusts, stripping all vegetation in their path. Little wonder that towns and villages became depopulated as their residents moved out of the way of these troop movements, or because they no longer had food to eat after the army had passed through.

Forcing armies to forage was not confined to the Bronze Age. During the crusades, between the 10th and 13th centuries AD, crusader knights and their entourage and supporters were renowned for their depredations of the European countryside as they made their way to the Holy Land. Both Napoleon and Wellington employed the same tactics in the late 18th and early 19th centuries AD.

Fleeing an attack: The second element results from the attacks on populated centres, such as the city states themselves. People fled before those attacks and the survivors often abandoned a decimated city to find new homes.

We also know from texts that, towards 1200 BC, certain parts of the Middle East suffered a drought and consequent famine, whilst others did not. For instance, the land of Hatti suffered whilst the cities in the southern Levant did not, or at least not as much. This would undoubtedly have led to migrations of part of the population of Hatti towards the Levant.

It could easily be imagined that, for numerous reasons, between about 1300 BC and 1100 BC, human migrations across the region were a regular occurrence.

Confusion at the time

There were so many groups active and mobile in the Middle East, some hostile, some peaceful, that there is little wonder that the Great Kings were sometimes confused as to their identities. Any one group, pirate, brigand, or refugee would have been made up of multiple ethnicities and races.

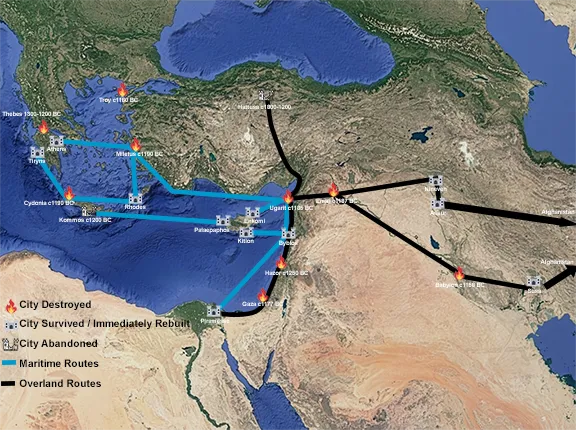

The ravages of the 'Sea Peoples'

We read above that after the Sea Peoples ravaged Anatolia, Cyprus, and Syria, they invaded Egypt about 1190 BC. Ramesses III defeated them on land at the Battle of Djahy, and at sea in the Battle of the Delta. Ramesses subsequently allowed some of the enemy survivors to live in five cities, the so-called Pentapolis of Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gath, and Ekron. These cities, on the coastal plain between modern Tel Aviv and Gaza were collectively known as Philistia, or the Land of the Philistines that the Greeks later called Palestine.It appears as though Ramesses recognised the destabilising influence of large numbers of immigrants, unwanted or otherwise and pro-actively resettled them in southern Canaan.

Modern interpretations

Some authors suggest that the Sea Peoples was a generic term used to describe an agglomeration of people: raiders arriving by sea with hostile intent, refugees and mercenary bands moving across the landscape, some immigrants with peaceful intentions, some with a more belligerent attitude.

Such an uncontrolled and uncontrollable movement of people would inevitably cause friction amongst entrenched communities, disruption to food supplies and trading routes and destabilise administrations.

Ignoring any racial or religious differences, large immigrant groups would compete with in situ communities for necessary resources, such as water, shelter, and food, not to mention land and work, creating animosity or worse between the two.

The Sea Peoples could easily have been a major factor in the decline of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East.

Victims of the ‘Sea Peoples’

Here are some of the key regions and cities purportedly attacked or significantly impacted by the Sea Peoples, based on Egyptian texts and archaeological evidence.

Anatolia (Modern-day Turkey)

Hittite Empire: The powerful Hittite Empire, a dominant force in Anatolia and northern Syria, appears to have been a major victim. Egyptian texts, particularly those of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, explicitly state that the Sea Peoples "laid their hands upon the land as far as the Circle of the Earth. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti [the Hittite Empire], Kode [Cilicia], Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya [Cyprus] on, being cut off at (one time)." While other factors certainly contributed to the Hittite collapse, the Sea Peoples were clearly a significant external pressure.

Hattusa: The Hittite capital, Hattusa, was violently destroyed around 1200 BC. While some scholars attribute this to internal conflicts or other invaders, the widespread regional devastation often linked to the Sea Peoples makes them a strong candidate for at least part of the destructive force.

Syria and the Levant (Modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel/Palestine):

Ugarit: This wealthy and strategically vital port city on the Syrian coast was a major trading hub, connecting the Aegean, Anatolia, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia. Archaeological evidence points to its sudden and violent destruction around 1190 BC. A famous letter from the last king of Ugarit, Ammurapi, to the king of Alashiya (Cyprus), describes enemy ships burning his towns: "My father, now enemy ships are coming (and) they burn down my towns with fire. They have done unseemly things in the land!" This provides a contemporary, though desperate, account of naval attacks, strongly presumed to be by Sea Peoples.

Amurru: A kingdom in coastal Syria, Amurru is specifically mentioned in Ramesses III's inscriptions as having been devastated by the Sea Peoples before they turned towards Egypt.

Various Canaanite Cities: Archaeological surveys in the Southern Levant show widespread destruction layers at many sites around 1200 BC. While specific attributions are difficult, some of the groups identified among the Sea Peoples, such as the Peleset (often linked to the Philistines), are believed to have settled in coastal Canaan (modern-day Gaza Strip and surrounding areas) after their defeat by Egypt. Sites like Ashdod, Ashkelon, and Gaza show evidence of cultural changes and the arrival of new populations that are sometimes associated with the Peleset.

Tel Dor: This significant port city on the northern coast of modern-day Israel shows signs of destruction and subsequent re-settlement by a group possibly identifiable as the Tjeker, another Sea People group.

Ancient Alashiya (Modern day Cyprus):

Egyptian records mention Alashiya as being amongst the lands "cut off" by the Sea Peoples. Archaeological sites on Cyprus, such as Enkomi and Kition, show evidence of destruction and abandonment around the end of the Late Bronze Age, consistent with widespread disruption and attacks.

Egypt:

Nile Delta: Egypt itself was the target of at least two major invasions by the Sea Peoples, famously recorded by Merneptah and Ramesses III. These were not mere raids but full-scale attempts at invasion, repelled by the pharaohs' armies and navies. The inscriptions at Medinet Habu (Ramesses III's mortuary temple) depict dramatic land and sea battles against the coalition of Sea Peoples. The attacks aimed at the fertile Delta, Egypt's breadbasket, indicate their migratory and resource-seeking motivations.

The Names of the Raiders

The Egyptian texts name various groups within the Sea Peoples confederacy, though their precise origins remain debated:

Peleset: Most famously associated with the Philistines, who settled in the southern Levant.

Tjeker: Possibly settled in the region of Dor.

Shekelesh: Sometimes linked to Sicily (Sikels).

Sherden: Often connected to Sardinia. They were known as mercenaries in Egyptian service even before the collapse.

Denyen: Possibly linked to the Danaans (Greeks) or from Adana in Cilicia.

Weshesh: Their origin is unknown.

Lukka: Known from earlier Hittite and Egyptian texts as raiders from western Anatolia (Lycia).

Ekwesh: Speculatively identified with the Achaeans (Mycenaean Greeks).

Teresh: Possibly linked to the Tyrrhenians (ancestors of the Etruscans).

While the exact causal relationship between the Sea Peoples and the Bronze Age Collapse remains a complex academic debate, their documented attacks on key port cities, their disruption of trade routes, and their attempts to invade fertile lands underscore their significant role in the era's widespread conflicts and the subsequent reshaping of Mediterranean power dynamics. They were, in many ways, the vanguard of a new age of maritime competition.

References

Astour, Michael C. "New Evidence on the Last Days of Ugarit." American Journal of Archaeology, 1965.

Cline, Eric. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed (2014).

Eachsmann, Shelley. Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant (1998)

Henry, James. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol. III.

Moran, William L. The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron