Civilisations that Collapsed

Late Bronze Age Civilisations of the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean

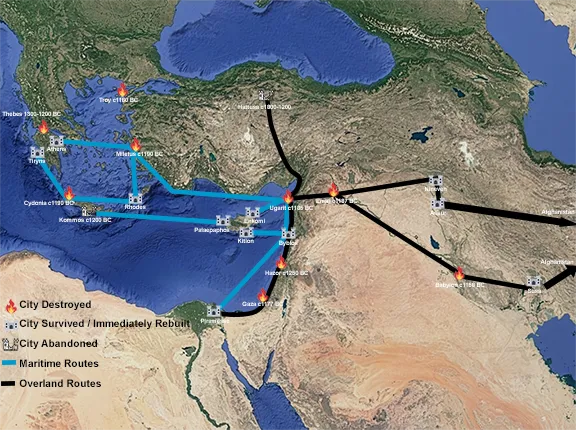

The Bronze Age civilisations of the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean started to emerge about 1750 BC. Most reached their peak of civilisation between 1380 BC and 1158 BC. All but two had gone by 912 BC. What caused the Bronze Age civilisations of the Middle East to collapse? Did they really collapse? This article is an overview of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean when they were at their peak. It was all downhill from there.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-04-21 | Last Updated 2025-11-25 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 6,486 times

Bronze Age Horned God - Enkomi Archaeological Museum

Mycenaean Civilisation (c 1750 to 1050 BC)

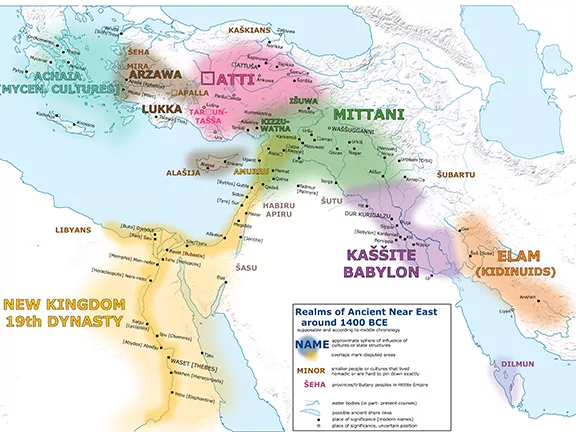

The Mycenaean civilisation reached its peak about 1350 BC, by which time its territory consisted of palatial states on mainland Greece, Crete, parts of western Anatolia and the Aegean islands as far as Rhodes. The palatial states boasted a complex administrative system. Work was divided among specialised departments, each handling specific trades and tasks. At the head of this society was the king, known as wanax.

Myceanean Political Structure

Mycenaean society was hierarchical and centred around powerful kings who ruled from their palatial centres. These kings managed the economy, religion, and military endeavours of their realms. The presence of a centralised authority helped in the efficient organization of labour, distribution of resources, and mobilisation for construction projects and military campaigns.

The palatial territory was divided into several sub-regions, each headed by its provincial centre. Each province was further divided in smaller districts, the damoi. On the Greek mainland, the palatial states were dominated by a warrior elite.

It is unclear at present whether the looser, palatial governance of Crete during the previous Minoan phase, was continued after the Mycenaeans became the elites on the island or whether Crete experienced the more rigid, traditional Mycenaean system.

Mycenaean Trading and Diplomatic Networks

By 1350 BC, the Mycenaean trading and diplomatic networks extended to all the Near Eastern civilisations, apart from the Hittite Empire, throughout the central Mediterranean and possibly as far as Italy and Spain.

In Hittite records, the Myceneans are referred to as Ahhiyawa from about 1400 to 1200 BC, whilst in Egyptian records, after 1200 BC, they are called Ekwesh, a possible reference to one of the groups making up the 'Sea Peoples'.

Mycenaean Kings

Unfortunately, little is known about individual kings or wanax of the Mycenaean civilisation, not even their names.

Mycenaean Society

Mycenaean Society was strictly hierarchical, valued family lineage, and awarded higher social status to those involved with religious or military activities and palatial administration. The lower classes contained craftsmen and artisans who worked for or provided goods and services to the palaces, as well as women and slaves. How the palatial and military elite treated the lowest echelons of their society is not known.

The Mycenaeans possessed a warrior elite and a strong military tradition, evident in their well-organised forces and the impressive fortifications they built around their settlements. This focus on defence and warfare suggests a society prepared for conflict. Their strategic positioning allowed them to not only safeguard their own lands but also project power outwards. This military strength proved instrumental in their rise to prominence, enabling them to extend their influence across the Aegean and even into Crete following the decline of the Minoan civilisation.

The Mycenaeans were considered by the Hittites, to be, to put it bluntly, a pain in the butt, a constant threat to the delicate balance of powers in the Near East. From the 15th right through to the 13th centuries BC, very few Mycenaean trade goods were accepted by the Hittite homelands in central Anatolia and, conversely, very few Hittite imports have been found on mainland Greece, Crete, the Cycladic islands, or Rhodes, even though both the Hittites and Mycenaeans traded with every other power in the Near East. There is even evidence that the Hittites imposed a deliberate embargo on goods to and from the Mycenaeans as we shall see in Chapter 6, 'When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins'.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Middle Babylonian Kingdom (c 1595 to c 1155 BC)

The Babylonian Empire under the Kassites, c.?13th century BC

Following the sack of Babylon by the Hittites under Mursili I in 1595 BC, the Mesopotamian kingdom of Old Babylon fractured. Instead of occupying Babylon, the Hittites withdrew which provided an opportunity for a local indigenous tribe from the Zagros Mountains northeast of Babylonia, the Kassites, to move in.

It would take another hundred years before the Kassites successfully reunited Babylonia and re-instated the lucrative trade connections enjoyed by the previous kings of Babylon. From then onward, the Kassite kings would adopt the title of 'King of Babylonia' and were referred by their regional neighbours as 'Kings of the land Karduniash', the latter being the non-Kassite term for Babylonia.

After re-unification in 1475 BC, the Middle Babylonian Kingdom is sometimes referred to as the Kassite period. They were at the peak of their power during the reign of Kurigalzu I about 1375 BC. During the reign of Kurigalzu II (1332 to 1308 BC), a new city was built at Dur-Kurigalzu where the Kassite kings were honoured by the chiefs of the Kassite tribes. It appears Babylon remained the capital.

Babylonian Political Structure

Little is known about how the Kassites controlled Babylonia. Much of the information will be on tablets found at Nippur that include administrative and legal texts, letters, seal inscriptions, private votive inscriptions, and even a literary text. Altogether there are about 12,000 tablets and inscriptions known from the Kassite period, only about 1,200 have so far been published.

From what little we do know, the Kassites had one king who ruled over Babylonia. It must have been relatively stable because there is little evidence of any political problems until the 13th century BC. The Kassite period in Mesopotamia saw a reshuffling of titles and roles in both the central government and provincial administration. New titles like kakruma (military chief) and kartappu (originally a horse driver) emerged near the king, while the existing sukkallu (minister) remained. The nobility, likely Kassite, held major positions.

Provinces (pihatu) were led by governors (sakin mati/saknu). Nippur's governor, the sandabakku, held more power according to extensive records found there. These positions were often hereditary. At the local level, hazannu (mayors) managed some judicial matters alongside dedicated dayyanu (judges). Babylonians filled most administrative jobs, suggesting a lack of Kassite interest in such roles. Taxes were levied, sometimes in the form of goods or services, with exemptions documented on kudurru monuments.

A unique Kassite contribution was the bitu ("house" system) led by bel biti (hereditary chiefs). Initially seen as tribal territories, this system is now viewed as a complementary administrative level with chiefs potentially appointed by the king.

The Kassite period in Mesopotamia also saw a surge in royal land grants documented on kudurru monuments. These grants, unlike previous periods, were permanent and sizable (250 hectares on average). Recipients were high-ranking officials, family members, the military, or priests, often as rewards for service. Major temples also received land grants, complete with workers. Some grants included tax breaks, forced labour, or even local governing power, leading some scholars to (mistakenly) compare this system to feudalism. However, most land remained under royal control and was managed traditionally. This system of land grants appears to be a Kassite innovation.

The Amarna letters, written between 1360 and 1332 BC, record some of the communications between the Kassite kings and Egypt, particularly Kadashman-Enlil I (1375 to 1360 BC) and Burnaburiash II (1359 to 1333 BC). The letters indicate that Babylonia traded with all the other powers in the region. They also indicate that Babylonia, during the Kassite period, was a member of the 'Great Powers Club.' This is a modern-day designation for the strongest nations of the region including Egypt, the Kingdom of Mitanni, and the Kingdom of the Hatti (Hittites) of Anatolia who had established norms for communication and desired to 'regulate peace and war, trade and marriages, border disputes and exchange of messages.' Between themselves, they were known as 'Great Kings' and other, lesser, kingdoms vied to join this exclusive club.

Kassite Kings of Babylonia

Kurigalzu I 1375, Burnaburiash II c1360, Kara-hardash c1333, Kurigalzu II c1332, Nazi-Maruttash c1308, Kadashman-Turgu c1282, Kadashman-Enlil II c1264, Shagarakti- Shuriash c1246.

Assyrian Kings of Babylon

Kashtiliash IV c1233 to c1225 BC Deposed by King Tukulti-Ninurta I during the Assyrian invasion of Southern Babylonia.

Enlil-nadin-shumi c1225 to c1224 BC Appointee of Tukulti-Ninurta I under Assyrian occupation of Southern Babylonia.

Kadashman-Harbe II c1224 to c1223 BC Appointee of Tukulti-Ninurta I.

Adad-shuma-iddina c1223 tp c1217 BC Appointee of Tukulti-Ninurta I.

Adad-shuma-usur c1217 tp c1187 BC (30 years) Descendant of Kashtiliash IV who gained the Babylonian throne after a revolt against Assyrian occupation.

Last Kassite Kings

Meli-Shipak c1187 tp c1172 BC

Marduk-alpa-iddina I c1172

Zababa-shuma-iddin c1159 tp c1158 BC Deposed by the Elamites after separate invasions by the Elamites and Assyrians.

Enlil-nadin-ahi c1158 - c1155 Deposed and captured by the Elamites after their invasion of Southern Babylonia, ending the Middle Babylonian period and Kassite dynasty.

Babylonian Society

Despite the change in leadership, Babylonian culture thrived. The Kassites themselves adopted the Akkadian language and Babylonian administrative practices. This period saw significant contributions to literature, mathematics, and astronomy, with Babylonian scholarship influencing the wider region. The Kassites prioritised economic development. They invested in irrigation projects to expand agricultural land, leading to increased prosperity. Additionally, Babylon remained a key trade centre, facilitating commerce between Mesopotamia and neighbouring regions.

Kingdom of Mitanni (c 1550 to c 1260 BC)

Kingdom of Mitanni about 1490 BC

The Mitanni kingdom, a powerful state that emerged around 1550 BC and was flourishing between 1500 and 1260 BCE, remains shrouded in mystery despite its past prominence. While its exact borders shifted throughout its history, Mitanni encompassed a vast region stretching from present-day northern Iraq through Syria and into Turkey. The capital, Washukanni, thrived near the headwaters of the Habur River, a tributary of the Euphrates.

While scant records exist about the Mitanni people themselves, glimpses of their prosperous civilisation emerge from various sources. The Amarna Letters, a collection of royal correspondence, highlight interactions with Egyptian and Assyrian kings. Additionally, the world's oldest horse-training manual and a treaty with the Hittites offer valuable insights. These fragments paint a picture of a thriving nation that, around 1350 BC, rivalled major powers like Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, and the Hittite Kingdom.

The Mitanni kingdom strategically controlled trade routes along the Habur and Euphrates rivers, extending their influence to Mari, Carchemish, Nineveh, and the upper Tigris. Their network of allies included Kizuwatna in Anatolia, Mukish in northern Syria, and the Niya kingdom controlling the eastern Orontes River valley.

Political Structure of Mitanni

Scholars believe the Maryannu, a warrior class, formed the ruling elite. The Maryannu were an elite caste of hereditary chariot-mounted warriors between about 1700 and 1200 BC in the Middle East. They reputedly fought for the pharaohs from light two wheeled chariots. The Egyptians translated "Mitanni" as "Naharin" and "Metani," suggesting a possible connection to the Maryannu. Assyrians referred to the kingdom as Hanigalbat, while Hittites called them the Huri or Hurrians, leading modern scholars to identify the Mitanni people with the Hurrians.

The Hurrians originated in the upper Habur and Tigris rivers up to the Taurus and Zagros mountains, especially around Lake Van. Their strategy since about 4000 BC, was one of military conquest mixed with the peaceful migration of Hurrian merchants, farmers, artisans, and nomads.

Mitanni's eastern borders enjoyed friendly relations with the Hurrian-speaking Kassites, who occupied a region roughly corresponding to modern-day Kurdistan. The Mitanni kingdom's northern Syrian territory stretched westward to border eastern Anatolia and eastward all the way to Nuzi (present-day Kirkuk, Iraq) and the Tigris River. To the south, their domain extended from Aleppo eastward across the Euphrates River to Mari.

Around 1350 BC, at the peak of its power and influence, the Mitanni Kingdom was a member of the "Great Powers Club." This term, used by modern historians, refers to the dominant states of the era in the Middle East and Egypt. These included Egypt, Babylonia, and the Hittite Kingdom, who interacted through trade and alliances.

Kings of Mitanni

While historical records detail the kings and their interactions with other nations, the daily lives and religious beliefs of the Mitanni people remain largely unknown. The destruction of their culture by the Assyrians later further hampered our ability to reconstruct their way of life. The early Mitanni kings are particularly obscure due to this cultural loss, though their names survive thanks to foreign correspondences. Those that came after 1350 BC are better known.

Tushrata c 1358, Artatama II c 1335, Shuttarna III c 1330, Shatiwaza c 1330, Shattuara c 1305, Wasashatta c 1285, Shattuara II c 1265.

Egyptian New Kingdom (c 1550 to 1077 BC)

Egyptian New Kingdom at ts greatest extent about 1380 BC

At the end of the Second Intermediate Period, during which the Hyksos ruled Lower Egypt from their capital at Avaris, and a succession of kings ruled Upper Egypt from Thebes, King Ahmose, completed the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt and consolidated his rule over the land, unifying Upper and Lower Egypt. With that, Ahmose ushered in a new period of prosperity, the New Kingdom. He and the kings that followed campaigned in the Middle East, extending Egypt's influence through the Levant as far north as Carchemish.

This resulted in a peak in Egypt's power and wealth about 1380 BC, during the reign of Amenhotep III (c 1391 - 1353 BC). The term pharaoh became a form of address for the person who was king during his reign.

Political Structure in the New Kingdom of Egypt

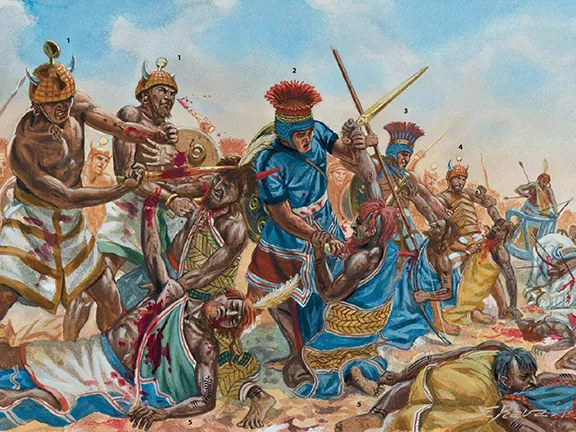

The rise of the New Kingdom in Egypt (after 1570 BC) saw a shift from self-assured isolation to active conquest. Believing their land held the key to divine harmony, the Egyptians took control of Canaan, Syria, and Nubia within just 50 years. Pharaohs sent Egyptians to settle these conquered lands, both to maintain control and exploit resources for the crown.

The New Kingdom pharaohs fostered loyalty in conquered lands through a clever strategy. They installed local leaders as puppet kings, but with a twist. These kings' sons were brought to Egypt, raised, and educated there. By the time they returned to rule, they were thoroughly Egyptianised, viewing Egyptian culture as superior, and were naturally more loyal to the pharaoh. This tactic secured control of conquered territories in the Near and Middle East without direct Egyptian rule.

The New Kingdom transformed Egypt into a powerful bureaucracy. The pharaoh divided the empire into two regions, Upper and Lower Egypt, each governed from a major city. Regional administrators managed taxes, labour conscription, and agriculture. A vizier, a powerful official, oversaw the entire system, even controlling the annual flooding of the Nile River, and personally decided when to open the sluice gates on the Nile to allow the floodwaters to irrigate the surrounding land each year.

The New Kingdom pharaohs, though seen as living gods, maintained control through a nuanced approach. While they held immense power through religious authority and military might, they also employed diplomacy. Letters reveal pharaohs negotiating and offering incentives like tax breaks and gifts to secure loyalty, rather than relying solely on threats. This suggests a more complex leadership style than simple divine coercion.

Kings and Pharaohs of Egyptian New Kingdom

Ahmose I 1550, Amenhotep I 1525, Thutmose I 1504, Thutmose II 1492, Hatshepsut 1479, Thutmose III 1479, Amenhotep II 1427, Thutmose IV 1401, Amenhotep III 1391, Akhenaten 1353, Smenkhkare 1336, Neferneferuaten 1335, Tutankhamun 1333, Ay 1323, Horemheb 1319, Ramesses I 1292, Seti I 1290, Ramesses II 1279, Memeptah 1213, Amenmesse 1203, Seti II 1203, Siptah 1197, Twosret 1191, Setnakhte 1190, Ramesses III 1186, Ramesses IV 1155, Ramesses V 1149, Ramesses VI 1145, Ramesses VII 1137, Ramesses VIII 1130, Ramesses IX 1129, Ramesses X 1111, Ramesses XI 1107 to 1077 BC.

Canaanite city states (from c 1500 BC)

Canaanite city states about 1200 BC

During the Late Bronze Age, Canaan was not a unified kingdom but a collection of independent city-states, each with its own ruler and sphere of influence. The region of Canaan roughly corresponded to the present-day Israel and the Palestine Territories, western Jordan, southern Syria, Lebanon and continuing up the coastal strip as far as the southern border of Turkey.

Their common denominator was their language, Semitic. At various times during the Bronze Age, parts of this vast territory came under the influence of the Egyptian, Hittite, Mitanni, and Assyrian Empires so that, by the late Bronze Age, the Canaanite cities were a cultural melting pot. Yet they all retained similar traditions including sacrificing a donkey under house foundations and more than a hint of child sacrifice.

Towards the end of the Bronze Age and into the early Iron Age, there is are indications in the archaeological record that, unlike other Levantine sites occupied by the Philistines where pig bones are regularly found, the eating of pigs, particularly in the western Canaanite sites, was becoming taboo. Was this an early expression of self-definition, or were they running out of pigs?

Where did the Canaanites come from?

A 2017 AD study led by geneticist Marc Haber of the Welcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK, successfully sequenced the entire genomes of five Canaanite individuals. The remarkably well-preserved remains, estimated to be 3,700 years old, originated from excavations in Sidon, a coastal city in modern-day Lebanon.

In a bid to understand the genetic makeup of the Canaanites, Haber turned to ancient DNA analysis. Drawing on historical accounts from the Greeks, which suggested an eastward migration into the Levant, Haber's team compared Canaanite genomes with those of other Eurasian populations. The results revealed a subtle picture. While the Greeks were not entirely wrong, their perspective needed revision. Haber's team discovered that Canaanite ancestry stemmed from two primary sources. Roughly half originated from local farmers who had settled the Levant roughly 10,000 years prior. The remaining half traced back to an earlier population identified through Iranian skeletal remains. The researchers estimate that these eastern migrants arrived in the Levant and intermixed with the local population around 5,000 years ago.

This finding fits with other recent studies of the Levant. Iosif Lazaridis, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, saw the same mix of DNA in the genomes of ancient skeletons from Jordan. "It's nice to see that what we observed wasn't a fluke of our particular site, but was part of this broader Canaanite population," Lazaridis says.

Having identified the genetic makeup of the Canaanites, Haber's next question was their fate. He compared their ancient genomes with those of ninety-nine Lebanese individuals and a broader dataset of hundreds more from genetic databases. The analysis revealed a strong link between the Canaanites and modern Lebanese. The present-day Lebanese population appears to have inherited over 90% of its genes from this ancient civilisation. The remaining 7% likely originated from migrations around 3,000 years ago, potentially linked to populations from Central Europe.

The people who were later to be called Phoenicians, considered themselves Canaanites or associeated themselves with a particular city, so we see Tyrenians, Sidonians and so on.

The Canaanite city states

Some of the prominent city-states of Canaan during the Late Bronze Age include:

Byblos: Situated on the Lebanese coast, Byblos is one of the oldest Canaanite cities. It is closely linked with the development of the coastal cities of Tyre, Sidon and Sarepta after about 2750 BC.

Sidon: Located in Lebanon, on the coast, equidistant between Tyre to the south and Beirut to the north.

Megiddo: Located in northern Israel, Megiddo was a vital trade centre and a powerful city-state. It controlled a vast territory and played a significant role in regional politics.

Hazor: Situated in northern Israel, Hazor was another prominent city-state known for its impressive fortifications and strategic location. It was a major centre of Canaanite culture and religion.

Jerusalem: Though not as powerful as other city-states during this period, Jerusalem was still a significant centre and later became the capital of the Kingdom of Judah.

Lachish: Located in southern Israel, Lachish was a fortified city that served as an administrative centre for the region. It was an essential point on trade routes and played a crucial role in the defence of Canaan against external threats.

Gezer: Situated in central Israel, Gezer was a well-developed city-state known for its advanced water management system and metalworking skills. Its importance was due in part to the strategic position it held at the crossroads of the ancient coastal trade route linking Egypt with Syria, Anatolia and Mesopotamia, and the road to Jerusalem and Jericho, both important trade routes.

Ashkelon: Located on the Mediterranean coast, Ashkelon was a major port city and a crucial centre for trade and commerce. It maintained close ties with Egypt and other regional powers.

Shechem: Was an ancient city in the southern Levant. It was the centre of a kingdom carved out by Labaya (or Labayu), a Canaanite warlord who recruited mercenaries from among the Habiru.

Jaffa: Jaffa was founded by the Canaanites and is now part of southern Tel Aviv.

Cyprus city-states (from c 1500 BC)

Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age about 1300 BC

Unlike the centralised monarchy of the Hittite Empire, Cyprus during the late Bronze Age exhibited a decentralised political structure more akin to that adopted by the Canaanites.

The island was not unified under a single ruler, instead, it consisted of several independent kingdoms. Archaeological evidence suggests the existence of at least nine major kingdoms, with smaller city-states and settlements likely present as well.

These kingdoms varied in size and power, with some holding considerable influence over trade and regional politics, while others were smaller and more localised.

Each kingdom typically had a central urban centre, functioning as a political, economic, and religious hub. These centres often housed impressive palaces and administrative buildings.

Due to the lack of extensive written records on the island, much of our understanding of these kingdoms comes from archaeological evidence and from correspondence, such as tablets recovered from other city-states in the Middle East where Cyprus was known as Alashiya. This makes it difficult to definitively reconstruct the specific political structures within each kingdom.

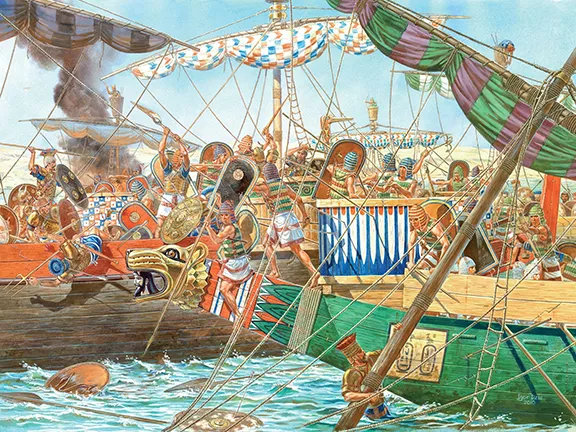

While independent, correspondence between states and empires such as the Amarna letters, suggest that these kingdoms interacted through alliances and trade networks. Evidence suggests some degree of collaboration, particularly in facing external threats like piracy or invasions. The name Alashiya, is found on texts written in Egyptian, Hittite, Akkadian, Mycenaean (Linear B) and Ugaritic.

The power dynamics between these kingdoms shifted throughout the period, with some kingdoms dominating trade or regional influence at certain points.

Recent research suggests a possible shift in social structures during the late Bronze Age, with the emergence of a more elite class alongside the existing populations.

While largely self-governing, Cyprus was not isolated from external influences. The island played a crucial role in trade between the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean, and external powers like the Hittite Empire and Egypt exerted some degree of influence on the island's politics and economy.

Major city states of Alashiya

Enkomi: Located on the east coast, Enkomi was a major trading centre and likely held significant political influence. Its extensive excavations have revealed impressive administrative and religious structures, though the term "palace" might not be universally applied to them.

Kition: Located on the south coast, Kition was another crucial trade centre and possessed a prominent urban centre with impressive buildings and fortifications. Like Enkomi, while influential, it might not be definitively classified as having a single, grand palace.

Hala Sultan Tekke: The city is located on the south coast, on the side of the present-day Larnaca Salt Lake, which in ancient times was connected to the Mediterranean, providing one of the best protected harbours on the island. Surveys indicate a city more than twenty-five hectares in size. The rich finds establish the multicultural nature of the inhabitants of the city, the wealth of which was based on trade and the export of copper and purple-dyed textiles. Imports and exports indicate cultural connections from Sardinia to Mesopotamia and from Scandinavia to Egypt in the period between 1650 and 1150 BC.

Paphos: Located on the west coast, Paphos emerged as an important centre later in the Late Bronze Age and continued to flourish in subsequent periods. Like other sites, while significant, it might not be classified as a single, centralised palace.

Kings of Alashiya

Only one king of Alashiya is known from correspondence sent to Ugarit during the 13th century. Ugarit was a major trading centre on the Syrian coast and a vassal city state of the Hittites. His name was Kushmeshusha. Although we do not know for sure which of the kingdoms Kushmeshusha ruled, it is likely to be Enkomi, which had at the time a major trading partner, Ugarit. In today's terminology Ugarit and Enkomi could be looked upon as twin towns.

Hittite Empire (c 1430 to c1180 BC)

.webp)

Map of the Hittite Empire about 1300 BC

At the height of its power, about 1330 BC, the Hittite Empire had its homeland in central Anatolia. The city states under the nominal control of the king in the capital city, Hattusa, included those in southeastern Anatolia, parts of north Syria and part of northern Mesopotamia. There were also several vassal city states in northern Canaan.

Hittite Political Structure

Anatolia's Hittite Empire pioneered one of the earliest known constitutional monarchies. The king held ultimate power, serving as military leader, judge, and high priest. The kingship was hereditary, and the king had a 'superhuman aura' and was referred to by the Hittite citizens as 'My Sun.' He retained control and his presence amongst his subjects by an annual tour of the Hittite holy cities, holding festivals and supervising the upkeep of sanctuaries. However, a network of officials wielded independent authority within specific governmental branches. Gal Mesedi (Chief of the Royal Bodyguards), was a prestigious position often held by royalty. The title was superseded by Gal Gestin (Chief of the Wine Stewards), who, like the Gal Mesedi, typically belonged to the royal family. The Gal Dubsar was Head of the Bureaucracy, distinct from the Lugal Dubsar, the king's personal scribe.

The vassal city-states were independently administered by their own kings and were bound to Hattusa by treaties and arranged marriages. After conquering a neighbouring city-state, it was not unusual for the original king to be returned to his throne, a strategy that sometimes backfired. Vassal states paid tribute to 'My Sun' and often negotiated their own treaties with city states in other empires.

Hittite Kings

The Hittite scribes kept voluminous records, written in Akkadian on clay tablets, such as the Boghazkoy Archive found at Hattusa and the Alalah Archive. From these it has been possible to identify some of the Hittite kings and some of the events that took place during their reigns.

Suppiluliuma I c 1350 BC, Arnuwanda II 1330 BC, Mursili II c.1330 BC, Muwatalli II 1295 BC, Mursili III 1272 BC, Hattusili III 1267 BC, Tudhaliya IV 1245 BC and the last king, Suppiluliuma II from1207 BC.

Hittite Queens

Unusually for this period, the Hittites revered and respected their queens. While information on the queens is limited, we do know that the title for the Hittite queen was 'Tawananna', suggesting that the position itself held considerable power and influence. However, the specific names of all but one of the Hittite queens have not yet been definitively established due to the fragmentary nature of historical records.

Wife of King Hattusili III (13th century BC), Puduhepa is the most well-known Hittite queen. She held significant political influence, participated in international diplomacy, and even had her own seal. Her role in the Hittite court and interactions with powerful rulers like Ramesses II of Egypt are well-documented through surviving texts.

While the king held ultimate authority, queens played a significant role in the Hittite court. They often served as advisors and confidantes to the king, wielding considerable political influence. There is evidence that some queens held prominent religious positions, further solidifying their power and influence.

Nature of the Hittite Society

The Hittite society was essentially feudal and agrarian, the common people being either freemen, artisans, serfs, or slaves. There is some evidence that the Hittite hierarchy had a more benevolent attitude to their serfs, and slaves, trying to provide for them in times of famine and having liberal, even lenient, policies towards conquered subjects.

The Hittites maintained their dominant position through a combination of diplomacy, threats, war, and trade. Of all the Bronze Age civilisations in the Near East, barring Egypt, it is the Hittites that seem to have their act together with a robust system of government and the ability to raise a considerable army when required, for defence or offense.

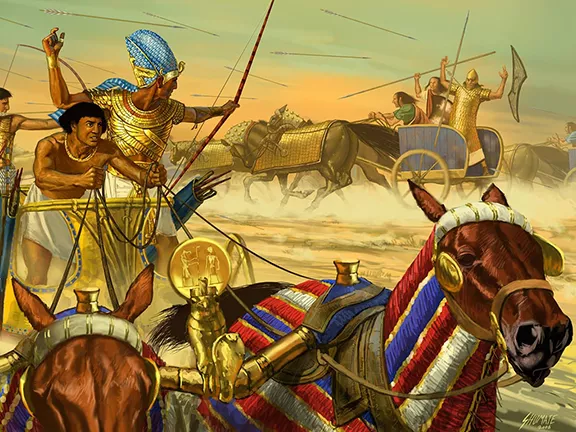

At the Battle of Qadesh (or Kadesh) in the spring of 1274 BC, Muwatalli II fielded an army of between 23,000 and 50,000 troops, including between 2,500 and 10,500 chariots, depending on whose account you believe, Hittite or Egyptian. The point here though, is that Hattusili enlisted help from the Hittite vassal states of Pitassa, the Seha River Land, Wilusiya, Carchemish, Mitanni, Ugarit, Aleppo, and Kadesh, all far from the capital. Muwatalli was clearly a man to be respected and obeyed.

Middle Assyrian Empire (c 1363 to c 912 BC)

Approximate map of the Middle Assyrian Empire at its height in the 13th century BC

The Middle Assyrian Empire emerged from the total disintegration of the Mitanni Kingdom and the partial disintegration of the Hittite Empire and the Middle Babylonian Kingdom. From being a city-state, subject to Mitanni rule, Assur achieved independence about 1363 BC, thanks to its first king, Ashur-uballit. He was taking advantage of Mitanni weakness during their conflicted with the Hittites. Ashur-uballit and succeeding kings progressively expanded Assyria, absorbing what had been the Mitanni Kingdom, segments of the Hittite Empire and reducing Babylonia to an Assyrian vassal state. The Middle Assyrian Empire reached its peak about 1225 BC after King Tukulti-Ninurta I defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Nihriya, and sacked Babylon in 1225 BC.

Political Structure of the Middle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian king held ultimate power, acting as both ruler and intermediary between the gods and the people. While lacking a formal cabinet, the king relied on advisors, particularly viziers (sukkallu) for political and diplomatic counsel. Grand viziers (sukkallu rabi'u) held even greater sway, often ruling conquered Mitanni lands and being hereditary members of the royal family.

A complex bureaucracy supported the king. Officials called "sa-resi" managed various tasks, tracking agricultural yields and livestock, managing gifts, overseeing land sales, and recording tribute, prisoners, and levies. The king maintained total control, intervening directly or through representatives (qepu) whenever needed.

The Middle Assyrian Empire divided its territory into provinces (pahutu), with the number fluctuating based on the empire's size. Each province had a governor (bel pahete) responsible for the local economy, public order, and storing and distributing goods. These goods were inspected annually by the central government. Governors also oversaw local production by craftsmen and farmers, ensuring their needs were met. A support system existed where governors could request aid from the king or other governors during shortages. All the provinces offered symbolic tributes to the god Ashur, signifying loyalty to the Assyrian king and his government.

The Assyrian Empire was not solely composed of provinces. Vassal states, like those ruled by the Mitanni grand viziers, existed outside the provincial system but still answered to the Assyrian king. Additionally, cities within provinces had their own administrations overseen by mayors appointed by the king. These mayors focused on local economies, like governors, but with less power.

The "ilku" system was another key aspect of Assyrian land management. Similar to feudalism, the king claimed most land, including private property. In exchange for working for the king, individuals received land. The type and amount of service varied, and refusal could lead to land loss. Over time, the system weakened as duties could be paid for or delegated, and land could be sold, severing the connection between service and the land.

Highly influential officials received "dunnu" settlements. Large, tax-exempt estates functioning as farmsteads. These were most common in western territories where local leaders needed more autonomy. Tell Sabi Abyad is a good example of a dunnu estate, with hundreds of free farmers and serfs working its vast agricultural land.

The Middle Assyrian Empire relied on a complex system to manage its workforce. Special tablets (le'anu) tracked available manpower, rations, and assigned tasks. Construction projects, such as those at Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta and Assur, utilised a workforce of around two thousand, drawn from cities (likely through the ilku system), alongside specialists like engineers and religious figures.

Understanding the Assyrian taxation system remains a challenge. While tax collectors existed, details on specific taxes are scarce. Only import duties on foreign goods (around 25%) are confirmed. Other revenue streams included plunder from conquered lands, ongoing tribute from vassals (madattu), and "audience gifts" (namurtu) from visiting dignitaries. These gifts could be substantial. One documented instance details 941 sheep offered to a prince.

Kings of the Middle Assyrian Empire

Ashur-uballit I 1363, Enlil-nirari 1327, Arik-den-ili 1317, Adad-nirari I 1305, Shalmaneser I 1273, Tukulti-Ninurta I, 1243, Ashur-nadin-apli 1206, Ashur-nirari III 1202, Enlil-kudurri-usur 1196, Ninurta-apal-Ekur 1191, Ashur-dan I 1178, Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur 1132, Mutakkil-Nusku 1132, Ashur-resh-ishi I 1132.

Elamite Empire (c 1210 to c 1100 BC)

Elamite Empire before conquest of Babylon about 1150 BC

In southwest Iran, Elam flourished for thousands of years. This region, encompassing parts of modern-day Khuzestan and Ilam provinces, also extended slightly into southern Iraq. Elam thrived for millennia (c. 3200 to c. 539 BC) as a collection of city-states rather than a unified ethnic nation. Awan, Anshan, Shimashki, and Susa were some of the prominent centres.

Evidence from Susa, a major city, suggests extensive trade networks reaching eastward to India. Elam's greatest power came during the Middle Elamite Period (c. 1500 to c. 1100 BC) when it transformed into an empire. It reached its peak about 1158 BC.

The "Elamisation" Process

The Middle Elamite Period witnessed three major dynasties and a fascinating trend known as "Elamisation". This refers to the spread of Elamite language, culture, and religion, particularly from south to north. The rulers' efforts to promote "Elamisation" highlight the diverse ethnicities encompassed by the term "Elamites." Scholars believe this process may have involved imposing the dominant culture, especially on the northern populations.

The Rise and Fall of Elamite Dynasties

Kidinuid Dynasty (c. 1500 to c. 1400 BC) Founded by King Kidinu, this dynasty established a new title, "King of Anshan and of Susa", signifying their control over both the north and south. They also initiated the "elamisation" policy.

Igihalkid Dynasty (c. 1400 to c. 1200 BC) Renowned for King Untash-Napirisha, this dynasty fostered religious tolerance. He constructed the temple complex of Dur-Untash (Chogha Zanbil), initially dedicated to Susa's god Insushinak. However, the vision expanded to encompass a grand ziggurat honouring various Elamite deities and those from surrounding regions. The complex was mysteriously abandoned after Untash-Napirisha's reign.

Sutrukid Dynasty (c. 1200 to c. 1100 BCE) Considered the most powerful, the Sutrukids established the Elamite Empire. King Shutruk-Nakhunte played a pivotal role. He initially focused on strengthening Elam's image through construction projects. Subsequently, he and his sons embarked on conquests, sacking Sumerian cities, defeating the Kassites of Babylonia, and even acquiring Mesopotamian artefacts like the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin. Elamite expansion continued until it was stopped by the Assyrians to the north. The empire's decline began after Shutruk-Nakhunte's death due to internal struggles and a lack of strong leadership.

References

Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Kingdom of the Hittites (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199279081.

Durant, W. Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Fields, Nic; illustrated by Donato Spedaliere (2004). Mycenaean Citadels c. 1350 to 1200 BC (3rd ed.). Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781841767628.

Georgiou, Artemis. (2017). Flourishing amidst a Crisis: the regional history of the Paphos polity during the transition from the 13th to the 12th centuries BCE. 10.2307/j.ctt1v2xvsn.16.

Kantor, H. J. "Mitanni." Oriental Institute of Chicago, Plant Ornament in the Ancient Near East, Ch. XIV, pp. 1-42.

Kriwaczek, P. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. St. Martin's Griffin, 2012.

Liverani, Mario (2002). Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of International Relations. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 15 - 27. ISBN 9780801871030.

Leick, G. The A to Z of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press, 2010.

Pritchard, J. B. The Ancient Near East, Volume I: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Van De Mieroop, M. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC. Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Schofield, Louise (2006). The Mycenaeans. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9780892368679.

Map Credits

Image Mycenaean Palace States Alexikoua, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhurderivative work: Ikonact - Near East topographic map-blank.svg for the background map. This map for the information, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28358963

The Babylonian Empire under the Kassites, c.?13th century BC. By MapMaster - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3655971

Egyptian territory under the New Kingdom, c.?15th century BC. By ArdadN, Jeff Dahl - Own work based on: Egypt 1450 BC.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4335117

Map of Canaan: By Claude Valette - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39613327

Cyprus: (Map drafted by Georgiou, Artemis, digital data courtesy of the Cyprus Department of Geological Survey)

Mitanni Empire: By Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhurderivative work: Zunkir (talk) - Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11552530

Approximate map of the Middle Assyrian Empire at its height in the 13th century BC. By Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhurderivative work: Zunkir (talk) - Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11552918

Map of Elam. By File:Near East topographic map-blank.svg: SemhurFile:Elam-map-PL.svg: Wkotwicaderivative work: Morningstar1814 - File:Elam-map-PL.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61956849

Websites

https://unbiasedhistory.org/unveiling-mycenaean-civilization/#The_Decline_and_Fall_of_Mycenaean_Civilization

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canaan

https://www.science.org/content/article/ancient-dna-reveals-fate-mysterious-canaanites

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron