Civilisations that Collapsed

The Bronze Age Great Powers Club and Fake News

From the Amarna letters, written between 1360 and 1332 BC, we can deduce that the purpose of the Great Powers Club, even though it was never known as such during the Bronze Age, was to maintain diplomatic relations between rival states and empires to keep the peace between them and foster trade and cultural relations. Sometimes, rival rulers used the diplomatic exchanges to spread fake news.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-07-18 | Last Updated 2025-11-24 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 4,323 times

Don't you throw your spears at me - Bronze Age Diplomacy Image: Painting by Igor Dzis/Karwansary Pub

The Family of Kings

Kings in the second millennium often viewed themselves as an extended family. Suzerain kings were considered "fathers" (abu in Akkadian) to their vassals, who were referred to as "sons" (maru). Sovereigns of equal rank, whether "great kings" or vassals of the same suzerain, addressed each other as "brothers" (ahu). The relationship between suzerain and vassal was further emphasised by terms like "master" (belu) and "servant" (wardu). This familial language reflects the ideal dynamics between rulers'; affection and protection from the suzerain (father) and obedience, respect, and tribute from the vassal (son). Equality between rulers was fostered through reciprocity, with an emphasis on gift-giving and exchange.

Emerging Great Kings

Over time, a new category of kings emerged, those without a human suzerain (answering only to the gods). These powerful monarchs began using the title "Great King" (sharru rabu) in the latter half of the second millennium. This elite group, described as a "closed club" by scholars like H. Tadmor and M. Liverani, determined who could join based on military success. For example, Assur-uballit I of Assyria earned his place among the "Great Kings" by defeating Mitanni, while Tarundaradu of Arzawa (eastern Anatolia) remained excluded due to his failure to conquer the Hittites. This hierarchy naturally influenced diplomatic relations, as each king sought alliances and connections with their peers.

The Great Powers Club

Whilst the 'Great Powers Club' or 'Club of Great Powers' is a term coined by modern historians, it came about because of the use, by Bronze Age rulers, of the term 'Great King' to refer to themselves as well as others they considered equal. During the Bronze Age, to be regarded and acknowledged as a Great King was a highly prized accolade.

As states went through the cycle of growth, expansion and decline, different states would be at their height at different times so membership of the Great Powers Club would change over time.

Long Standing members of the Great Powers Club

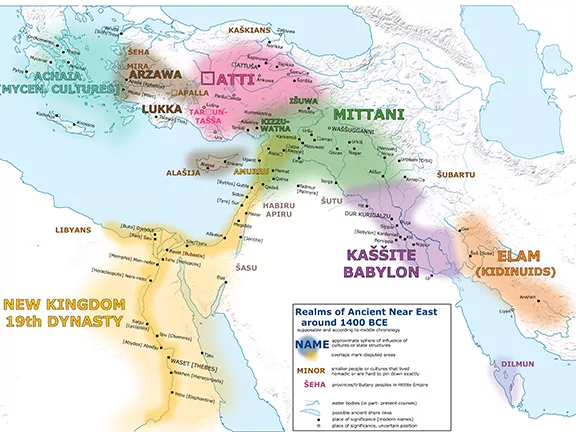

The longest standing members of the club, Egypt, the Hittites, and Kassite Babylonia, were joined at various times by Assyria, Mitanni, Alashiya (Cyprus), Ahhiyawa (north western Anatolia and Aegean, possibly those collectively known now as Myceaneans.) and Arzawa (in southwest Anatolia).

There are instances of Great Kings refusing to acknowledge another king's equality, thereby denying him membership of the club. As empires faded, so their kings were reduced in stature, resulting in he and his crumbling empire being excluded from the club.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Great Kings and Fake News

Like any rulers, the Great Kings understood the importance of a well-oiled communication network. A steady flow of accurate information between royal courts was crucial for maintaining dominance and fostering peaceful relations. However, a new challenge emerged, the spread of misinformation, which we might call "fake news" today.

Kings Craved Reliable News

The Great Kings hungered for news from other kingdoms, particularly regarding matters of shared concern like political shifts or devastating plagues. Messengers and envoys served as the primary channels for official communication. Kings actively encouraged a high volume of envoys to ensure a constant stream of information. Conversely, any disruption in this flow, such as a king hindering an envoy's travel, could trigger a decline in relations. The lack of official channels for information exchange often led to misunderstandings.

Fake News, a Threat to Stability

Given the vast distances between kingdoms and the slow pace of travel (compared to our modern world), relations were particularly vulnerable to various forms of misinformation. This included unintentional mistakes, deliberate attempts to spread disinformation, and of course, the ever-present court gossip and rumours. These "whispers" posed a significant threat to international diplomacy, trade networks, and the free movement of people between states.

Combating Rumours Through Diplomacy

Rumours, especially, were a major concern. They had the potential to disrupt friendly economic policies and peaceful diplomacy, ultimately jeopardising prosperity. To counter this, the Great Kings actively pursued cooperation and resolved disputes through diplomatic channels. Regular exchanges of messages, frequent envoy visits, and even rare face-to-face meetings were all employed in this effort. Notably, the exchanged letters often emphasised the kings' desire to avoid misunderstandings and the related complications.

Case Study - The Perils of Court Gossip

A prime example of this struggle comes from the correspondence between Egypt and Babylon, preserved in the Amarna Letters. These letters, named after their discovery site, reveal tension between the two powers. Interestingly, the source of this tension seems to be a negative experience by a Babylonian envoy at the Pharaoh's court, coupled with court gossip concerning the well-being of a Babylonian princess residing in Egypt during Amenhotep III's reign.

Amenhotep III's Rebuttal

To address the rumours and false reports delivered by the Babylonian envoys regarding the princess's fate, Amenhotep III himself wrote to his counterpart, King Kadasman-Enlil I of Babylon. He expressed his dissatisfaction with the unqualified Babylonian envoys, who apparently failed to recognize the princess:

'Did you, however, ever send here a dignitary of yours, who knows your sister, who could speak with her and identify her?' (Amarna Letter EA 1).

Amenhotep III Counters the Misinformation

Determined to be the sole source of truth, Amenhotep III directly addressed the "fake news" about the princess. He emphatically stated she was still alive and questioned the logic behind concealing her death if it had occurred. Furthermore, he challenged Kadasman-Enlil I with a pointed suggestion:

"Why don't you send a high-ranking official who can verify the truth for yourself? This person could personally witness your sister's well-being, her living quarters, and her interactions with the king."

This approach aimed to absolve himself of any accusations of dishonesty. To further solidify his claim, Amenhotep III included a sworn statement in the letter denying any motivation to deceive.

Case Study - Ramesses II and Puduhepa

A comparable situation arose during the reign of Ramesses II, who, like Amenhotep III a century before, married Babylonian princesses. Babylonian messengers, once again, spread false information about their treatment during visits to see the princesses in Egypt. This caught the attention of Puduhepa, wife of the Hittite king Hattusili III. Following the peace treaty between their kingdoms, Puduhepa mentioned this issue in her letters to Ramesses II.

Unfortunately, Ramesses II's response directly refuting Puduhepa's accusations is lost. However, we have Puduhepa's reply, which reveals parts of Ramesses' original letter:

"You, my brother, wrote: 'My sister [one of the princesses] wrote to me, saying, "When messengers came to visit the Babylonian princess who was married to the Egyptian king, they were left waiting outside!" It was Ellil-bel-nishe, the Babylonian king's own messenger, who told me this.'" (Catalogue of Hittite Texts 176)

Puduhepa's response highlights the perplexing nature of this gossip reaching her, a Hittite queen, through a Babylonian envoy. It suggests that such rumours were a common thread in international relations, used to assess reactions and shape perceptions of rivals. Interestingly, the practice of using precise quotes to avoid misunderstandings, as seen in Ramesses' response, remains relevant in diplomacy today.

Case Study - Delayed Envoys

The Amarna Letters provide further evidence of how rumours and misinformation plagued ancient diplomacy. A letter from King Tusratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep III of Egypt highlights this issue. Amenhotep had sent Mane, a high-ranking official, to escort Tusratta's daughter to Egypt for marriage. Time passed with no word from Mane, prompting Amenhotep to likely believe Mane was dead or ill.

Tusratta's Reassurance

Tusratta responded, explaining the delay. He assured Amenhotep that Mane was safe and well-treated. The delay stemmed from the time needed to prepare the princess's dowry and journey:

'For this reason, Mane has been detained here a while. I was going to send Keliya and Mane promptly, but I had not finished . . . I did not do the work, in order to do ten times more for my brother's wife. But now I will do the work.

Within six months I will send Keliya, my messenger, and Mane, my brother's messenger. I will deliver my brother's wife and they will bring her to my brother.' (Amarna Letters EA 20).

This incident demonstrates how even a simple delay could spark unfounded rumours.

Case Study - Slander and Backstabbing

Tusratta, in a separate letter (EA 24), expressed frustration with the "evil words" whispered against him to Amenhotep. He felt compelled to defend himself against these accusations, highlighting the prevalence of gossip in this era:

'And I want to say one thing more to my brother: In the presence of my brother evil words are numerous; one, who speaks (to him), is not (however,) at hand, those (evil words) do not come before the sight of a great one. (Now, however) an evil word was spoken (?) to the king; a babbler (?) has in a bad manner spoken to my brother concerning my person, he has denounced me.'

Even the 'Great King' Tusratta felt compelled to exonerate himself of slander that someone had pronounced against him before Amenhotep III.

The Importance of Communication

The Amarna Letters illustrate how crucial clear communication was for ancient rulers. Unanswered questions and delays fuelled rumours and mistrust. Notably, the Assyrian king Ashur-uballit felt compelled to explain the delay of Akhenaten's messengers due to threats from the Suteans: 'As to your messengers having been delayed in reaching you, Suteans had been their pursuers (and) they were in mortal danger. I detained them until I could write and the pursuing Suteans be taken for me.' (Amarna Letters EA 16)

However, the letter also hints at potential dissatisfaction with the meagre Egyptian gift and the delay in replying may have been petulance:

'Is such a present that of a Great King?' Gold in your country is dirt; one simply gathers it up. Why are you so sparing of it?? I am engaged in building a palace. Send me as much gold as is needed for its adornment.'

Maintaining Diplomatic Ties

Similarly, King Hattusili III expressed concern when Babylonian king Kadaman-Enlil II stopped sending envoys. Kadasman-Enlil blamed hostile Ahlamu people and the Assyrian king for the stoppage:

'Since the Ahlamu are hostile I have stopped sending my messengers. The King of Assyria prevents my messenger from crossing his territory.'

Hattusili, however, remained sceptical, implying that only hostile kings severed diplomatic communication:

'Only when two kings are at enmity do their messengers cease regular travel between them.' (Exchange between Hattusili III and Kadasman-Enlil II).

Lessons from the Past

These exchanges show how, just as today, accurate information flow was vital for successful diplomacy and peace in the ancient world. Discerning truth from whispers and hidden agendas was a crucial skill for diplomats of the past.

How Diplomacy Developed during the Bronze Age

In the article Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires, we came across the 'Great Powers Club' and how the club fostered diplomatic relations between the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East. The article also looks at how diplomacy developed over the period.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

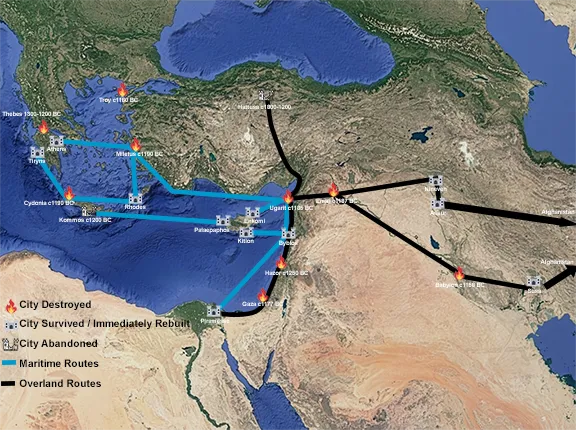

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron