Civilisations that Collapsed

Diplomacy in Action During the Bronze Age

We have looked at how diplomacy in the Middle East developed during the Bronze Age in the article, 'Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires.' Now we can look in more detail at how aspects of that diplomacy were conducted by the Great Powers.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-15 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 2,805 times

When diplomacy ends, war begins

The Bronze Age Great Powers

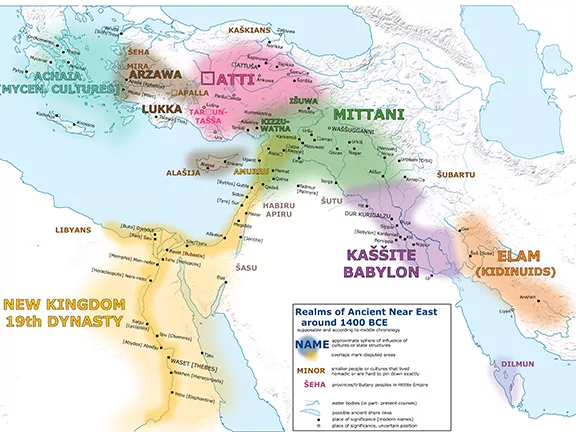

The Late Bronze Age Middle East was a dynamic arena dominated by a shifting cast of powerful states. Egypt, under the military prowess of Thutmosis III, initially held sway over a vast territory stretching from Upper Nubia in the south through Palestine and Syria to the western fringe of Mesopotamia. However, this hegemony was challenged by the rising kingdom of Mitanni, which asserted dominance over northern Mesopotamia and Syria, encroaching on Hittite interests in Anatolia.

Suppiluliuma's decisive defeat of Mitanni elevated the Hittite Empire to unrivalled supremacy. Under his son, Mursili II, Hittite dominion expanded from the Aegean coast eastwards across the face of Anatolia, through former Mitannian territory in northern Syria to the Euphrates region where Carchemish, formerly a Mitannian stronghold, became a key administrative centre.

As Mitanni waned, Assyria emerged as Hatti's primary rival. Having absorbed the remnants of Mitanni east of the Euphrates, Assyria's gaze turned westward towards Hittite territory. Yet, internal concerns, particularly with neighbouring Babylon, diverted Assyria's ambitions. Tukulti-Ninurta I temporarily incorporated Babylon into his empire, underscoring the region's fluid power dynamics.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Late Bronze Age Geopolitical Landscape

The geopolitical landscape of the Late Bronze Age was in constant flux. Empires rose and fell, borders shifted, and alliances formed and dissolved. A rare period of relative stability emerged with the thirteenth-century 'Eternal Treaty' (sometimes known as the 'Silver Treaty') between Egypt and Hatti. By this time, the once-mighty Mitanni had vanished, and the remaining great powers, Egypt, Hatti, Assyria, and Kassite Babylon, were engaged in a complex diplomatic equilibrium.

Egypt and Hatti undeniably emerged as the preeminent powers of the Late Bronze Age. While the treaty between Ramesses and Hattusili established a framework for peace, tensions persisted. Nevertheless, the immediate threat of war was averted, and a crucial demarcation of spheres of influence was agreed upon. Kadesh and Amurru, long-disputed territories, were ceded to the Hittites, while Egypt maintained control over much of Palestine and a coastal strip extending north to Sumur. Both empires acknowledged and respected the other's territorial boundaries.

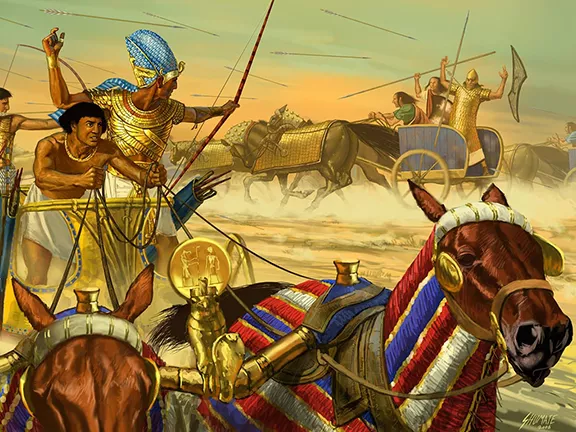

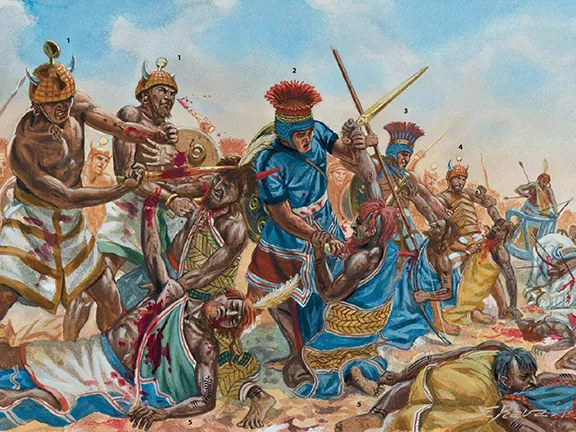

Bronze Age Warfare

It is essential to recognize that extended periods of peace were anomalies in this era defined by conflict. War was endemic, a cornerstone of the Late Bronze Age world order. Great Kings were expected to prove their valour in battle, acquiring spoils of war, goods, livestock, and human captives, to reward their armies, honour their deities, and enrich the state. Military prowess was inextricably linked to the very concept of kingship, a standard by which rulers were measured.

Wars were waged for various strategic objectives in the Late Bronze Age. Territorial expansion, control of trade routes, and defence of borders were common motivations. While conflict was prevalent, direct confrontation between the major powers was surprisingly infrequent.

The protracted hostilities between Hatti and Mitanni, culminating in Suppiluliuma's triumph over Tushratta, stand as a notable exception. Additionally, the battles of Kadesh involving Muwatalli II and the Egyptian pharaohs Seti I and Ramesses II, as well as the Assyrian defeat of Hittite forces under Tudhaliya IV at Nihriya, represent significant clashes. Sporadic skirmishes and incursions into rival territories also occurred. In addition, the late Bronze Age witnessed an increase in tensions between Assyria and Babylon.

Given the competitive nature of the era and the overlapping spheres of influence, the relative paucity of direct conflicts between the Great Kings is intriguing. Several factors may account for this. The immense costs of warfare, both human and economic, likely deterred prolonged hostilities. Moreover, the intricate web of diplomatic relations and alliances, often reinforced by intermarriage, may have served as a deterrent. The threat of coalition-building among rival powers could also have influenced decisions to avoid direct confrontation. Additionally, the pursuit of other strategic objectives, such as economic expansion or internal consolidation, may have taken precedence over outright warfare.

Ultimately, the complex interplay of these factors contributed to the sporadic nature of large-scale conflicts among the great powers of the Late Bronze Age.

Benefits of Hindsight

The lessons of the past were not lost on the leaders of the Late Bronze Age. While the allure of military glory persisted, a growing awareness of the limitations of conquest emerged. The ephemeral nature of earlier empires, despite their initial brilliance, served as a reminder of the challenges inherent in imperial expansion. For instance, Hattusili I, a Hittite king, sought to emulate the legendary achievements of Sargon and his son, Naram-Sin, whose exploits became the stuff of epic tales. Mursili I, another Hittite ruler, earned a place in his nation's military annals by conquering both Aleppo and Babylon. Similarly, Tuthmosis III's unparalleled victories in Syria established him as a quintessential warrior-pharaoh, inspiring subsequent Egyptian monarchs.

Previous kingdoms had faltered in maintaining control over their conquered territories due to insufficient resources, experience, and expertise. Moreover, their inability to engage in diplomatic negotiations with neighbouring states over disputed lands contributed to their downfall. Had these earlier powers cultivated diplomatic relationships with rivals vying for the same regions, they might have prolonged their dominance.

Statesmen and diplomats began to appreciate the potential of soft power to complement, or even supplant, military might. Strategic alliances carefully cultivated relationships, and the art of negotiation offered alternative pathways to influence and prestige. By fostering stability and cooperation, these diplomatic endeavours could create a more enduring legacy than the fleeting triumphs of the battlefield.

The reigns of Hatshepsut and Amenhotep III, a period marked by economic prosperity and monumental building projects rather than military aggression, became a model for some. It demonstrated that greatness could be achieved without resorting to constant warfare. As the Late Bronze Age progressed, a subtle shift in priorities became evident. While the dream of empire persisted, the means to achieve it were becoming more nuanced and less reliant solely on military force.

Geographical Factors

Geographical factors significantly influenced the dynamics between the Great Kingdoms. Egypt's isolated position removed it from the immediate proximity of its rivals. The vast expanse of Syria-Palestine, a region coveted by both Egypt and Mitanni, initially served as a battleground. However, a pragmatic division of this territory allowed both powers to secure substantial domains and access to vital coastal resources, ultimately paving the way for a more stable relationship.

Hatti's core territory in Anatolia and Egypt's primary interests in the south limited their direct territorial ambitions. The buffer states of Amurru and Kadesh, once fiercely contested, were ultimately ceded to Hatti, facilitating the landmark treaty with Egypt. The Eternal Treaty marked a pivotal moment, establishing a mutually beneficial arrangement that respected the territorial aspirations of both empires.

Kassite Babylon, focused on Mesopotamian affairs, posed no immediate threat to the Hittite states in Syria or Egyptian spheres of influence. While Assyria's growing power constituted a potential challenge, it did not translate into aggressive westward expansion during this period.

In conclusion, the Late Bronze Age, despite its reputation for conflict, witnessed periods of remarkable cooperation among the major powers. Geographic factors, combined with pragmatic diplomacy and a shared understanding of the limitations of perpetual warfare, fostered a degree of stability. While the spectre of conflict was never entirely absent, the prevailing trend was towards a more balanced and interconnected regional order. The exception to this was the constant rivalry between Hatti and Mitanni.

Diplomacy Fails Hatti versus Mitanni

The rivalry between Hatti and Mitanni was a protracted and bitter one, rooted in fundamental geopolitical and strategic imperatives. Mitanni, a formidable power forged through alliances and vassalage, had established a dominant presence across northern Mesopotamia, Syria, and parts of Anatolia. This effectively excluded Hatti from the vital Syrian region, a situation intolerable for a kingdom aspiring to great power status.

More critically, Mitanni's expansion brought it dangerously close to the Hittite heartland. The presence of Hurrian populations (the dominant ethnic group in Mitanni) in eastern Anatolia, potentially of ancestral origin, exacerbated the threat. Recurrent Hurrian attacks on the Hittite homeland, beginning under Hattusili I and persisting through subsequent reigns, underscored the existential nature of the challenge. Hatti's security was inextricably linked to the expulsion of hostile Hurrian forces from its borders.

On the other hand, Mitanni was equally resolute in defending its territorial integrity. The northern Syrian states, many with Hurrian populations, were vital to the kingdom's economic prosperity and strategic depth. To cede this territory to Hatti would be tantamount to surrendering a cornerstone of Mitannian power. The uncompromising positions of both kingdoms left little room for diplomatic resolution. The stage was set for a protracted conflict that would ultimately culminate in Hatti's decisive victory and the eclipse of Mitanni as a great power.

The Complexities of Great Power Relations

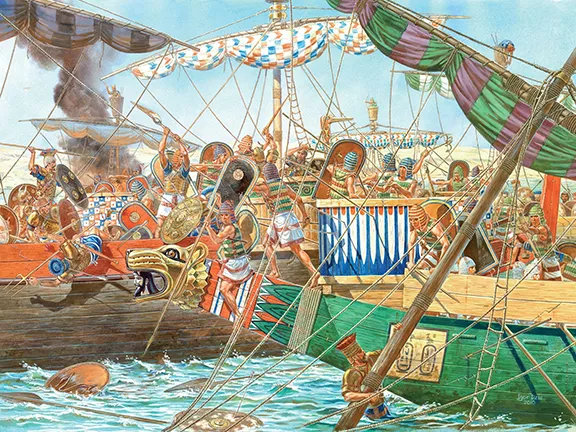

Geographical proximity was undoubtedly a key factor shaping relations between the great powers. However, other considerations also significantly influenced their interactions. The constant demands of internal and external security often diverted the focus of these empires from direct confrontation. Egyptian pharaohs, for instance, were preoccupied with maintaining control over Nubia, suppressing rebellions in their Asiatic provinces, and defending against Libyan incursions. Simultaneously, they faced the maritime threat posed by pirates, precursors to the formidable Sea Peoples.

Hittite kings were similarly burdened. Campaigns against rebellious territories within Anatolia and Syria were commonplace. Moreover, the persistent threat posed by the Kaska tribes from the north required constant vigilance. These tribes were quick to exploit any weakness as a result of Hittite military resources being heavily committed outside the heartland. These internal and external challenges placed immense strain on the resources of both empires.

Large-scale wars between great powers were incredibly costly and risky. They drained resources, weakened defences, and exposed the heartland to vulnerabilities. Consequently, rulers often prioritized resolving disputes through diplomacy rather than resorting to all-out war. Such an approach allowed them to conserve resources for more pressing threats and to reap the benefits of peaceful relations.

Economic considerations further reinforced the imperative for cooperation. The Late Bronze Age witnessed a flourishing of international trade, connecting the Near East with the Aegean world. Products from Crete and Mycenaean Greece flowed into the Middle East. Copper from Cyprus was a commodity as desirable, if not quite as essential, then as oil is today. This intricate network of exchange depended on a degree of stability and security provided by the great powers. Peaceful coexistence among these empires fostered a conducive environment for trade, generating wealth and prosperity for all involved.

Bronze Age Embargos

Trade, or rather, the denial of it, could also be used as a weapon to weaken an enemy.

During the latter part of the 13th century BC, Mycenaean Greeks were encroaching on Hittite territory in western Anatolia. This is the period of the Trojan Wars and the sack of Troy. They were being actively encouraged by Assyria. In 1225 BC, a treaty signed between the Hittite king Tudhalyia IV and the king of Amurru, Shaushgamuwa, apparently established an embargo that prevented products from Ahhiyawa (Mycenaean territories), passing through the coastal region of Amurru, into Assyria. By all accounts, this embargo worked, certainly there have been very few Mycenaean artefacts found from this period in Assyrian territories, compared to all other areas of the Middle East.

Bronze Age Communications

Effective communication was essential for maintaining diplomatic relations and preventing misunderstandings that could escalate into conflict. While personal meetings between rulers were rare, the exchange of letters served as a vital channel for conveying messages, negotiating treaties, and resolving disputes. This diplomatic correspondence provided a foundation for building trust and cooperation among the great powers.

As Adolf Hitler famously proclaimed: 'When diplomacy ends, war begins.'

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron