Civilisations that Collapsed

The Collapse of the Bronze Age Kingdom of Mitanni

The Kingdom of Mitanni was the first of the bronze age civilisations to disintegrate from being a member of the 'Great Powers Club' along with Egypt, Babylonia, and the Hittites, to total expunction. Mitanni reached its peak during the reign of Shuttarna II who ruled about 1400 to 1380 BC. The Kingdom had disappeared by 1245 BC, barely 135 years later.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-07-20 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 6,088 times

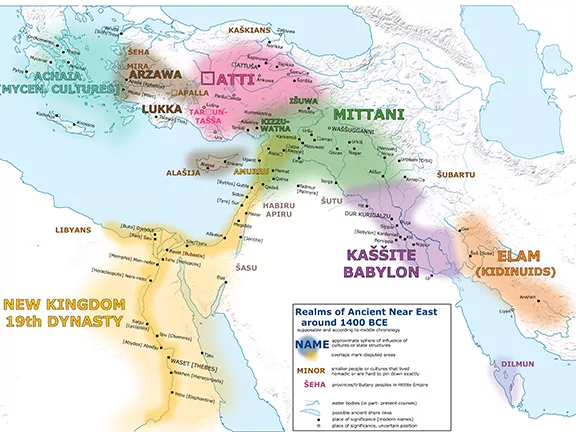

The Kingdom of Mitanni about 1400 BC

The Kingdom of Mitanni at its Peak

Washukanni, situated near the headwaters of the Habur River, served as the capital of the mighty Mitanni kingdom. The Habur, a tributary of the Euphrates, played a vital role in Mitanni's prosperity. It controlled trade routes running downriver to Mari and up the Euphrates to Carchemish. Their influence extended further east, encompassing the upper Tigris and its headwaters at Nineveh.

The Mitanni fostered strategic alliances, solidifying their regional presence. Kizuwatna in southeastern Anatolia, Mukish stretching between Ugarit and the Orontes River, and the Niya controlling the east bank of the Orontes, all found themselves aligned with the Mitanni. This network stretched from Alalakh down through Aleppo, Ebla, and Hama to Qatna and Kadesh in modern-day Syria.

Eastward, the Mitanni enjoyed good relations with the Hurrian-speaking Kassites, whose territory overlapped with present-day Kurdish-inhabited area. The Mitanni heartland encompassed northern Syria, bordering eastern Anatolia to the west, and reaching as far east as Nuzi (present-day Kirkuk, Iraq) and the Tigris River. The southern boundary stretched from Aleppo to Mari on the Euphrates. This fertile region allowed the Mitanni to grow enough crops to support their population without the land requiring extensive irrigation. Herds of cattle, sheep, horses, and goats thrived here, and the Mitanni were renowned horsemen and charioteers.

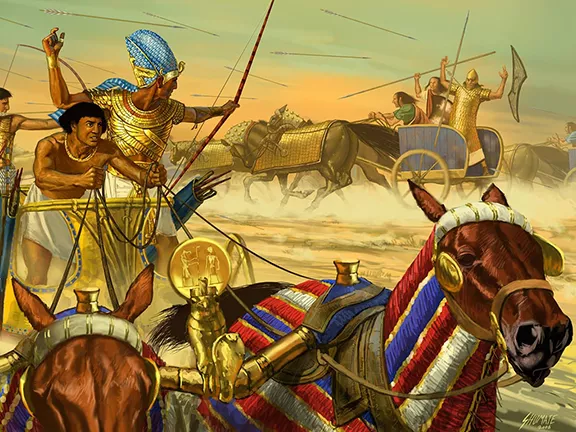

Pioneering innovation defined the Mitanni military. They are credited with developing the light war chariot, a technological leap forward. Unlike the cumbersome solid-wheeled chariots of the Sumerians, the Mitanni chariots boasted spoked wheels, making them lighter and more manoeuvrable, granting them a significant tactical advantage.

Further evidence of Mitanni's equestrian expertise comes from the Hittite archives unearthed at Hattusa (near modern-day Bogazkale, Turkiye). These archives contain the oldest surviving horse-training manual, a four-tablet masterpiece penned by Kikkuli, a Mitanni horse trainer, in 1345 BCE. The manual, beginning with the iconic inscription "Thus speaks Kikkuli, master horse trainer of the land of Mitanni," meticulously details the proper methods of horse training.

During its zenith, the Mitanni enjoyed a period of positive diplomatic relations with Egypt, another major power of the ancient world. Mitanni had previously challenged Egypt, successfully, over control of parts of northern Syria. With the ascendency of the Hittite Empire, on the northwestern borders of Mitanni, the Hittites became a major threat to Mitanni and Mitanni endeavoured to enrol Egypt as an ally.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Marriage, Diplomacy, and Conflict

In about 1378 BC, Mitanni King Shuttarna II married his daughter, Gilu-Hepa, off to the Egyptian pharaoh, Amenhotep III (c 1386-1353 BC). To mark the occasion, Amenhotep commissioned a special issue of scarabs. He recorded that, 'the princess was escorted by 317 ladies-in-waiting, women from the Mitanni king's royal palace.'

Gilu-Hepa became known as the "Secondary King's Wife," meaning she was secondary to Amenhotep III's chief wife, Queen Tiye.

Assyrian Threat

Meanwhile, Assyria was on its way to becoming a major player in the eastern part of the region. The Assyrian king, Ashur-Uballit I (c 1365 to 1330 BC) annexed significant parts of Mitanni territory, severely weakening the kingdom.

Second Royal Marriage

Twenty-six years after the marriage of Gilu-Hepa, king Tushratta of Mitanni (c 1358-1335 BC) and Pharaoh Amenhotep III of Egypt sought to reinforce the political alliance through the marriage of Tushratta's daughter, Princess Tadukhepa, Gilu-Hapa's niece, to the Egyptian Pharaoh.

Both diplomatic unions aimed to maintain a balance of power in the region during the 14th century BC. Egypt, already concerned about Hittite expansion now also had to contend with a potential threat to its north Levantine territories from an emerging Assyria.

Tadukhepa 's arrival in Egypt was accompanied by a substantial dowry, documented in surviving correspondence between the two monarchs. The list included gold, elaborately decorated horse saddles and camel litters, jewellery, and luxurious garments. Significantly, the dowry also included a statue of Sauska, the Mitannian goddess of fertility and healing. This dual aspect of Sauska's character suggests a multifaceted purpose for her inclusion. She may have been intended to bless the marriage and ensure its fruitfulness, while also offering potential alleviation for Amenhotep III's documented health concerns at the time.

The alliance faced challenges. One source of tension arose from a perceived discrepancy in the amount of gold exchanged during the marriage negotiations, as evidenced by letters from Tushratta to Amenhotep III. A more critical test came in the form of a power struggle within Mitanni itself.

A relative of Tushratta, possibly his brother Artatama II, challenged his authority in a coup attempt. Egypt initially supported Tushratta, while the Hittite king, Suppiluliuma I (c 1344-1322 BC), sided with Artatama II.

Paul Kriwaczek highlights the strategic significance of the region, stating that the Hittites "vied with the kingdom [of] Mitanni which had sealed off the Mesopotamian north all the way from near the sea in the west to the mountains in the east, from the area of Aleppo to the region of Kirkuk."

The Hittites likely saw an opportunity to disrupt Mitanni's control over trade routes by backing Artatama II.

Mitanni becomes a Hittite vassal

Despite initial Egyptian support and the backing of his own nobles, Tushratta' s position ultimately weakened. Fearing the growing power of the Hittites, Egypt withdrew its backing, leaving Tushratta vulnerable. Seizing the opportunity, Suppiluliuma I launched a military campaign that culminated in the sacking of Washukanni, the Mitannian capital. Tushratta's assassination by his son, Shattiwaza, possibly a desperate attempt to appease the Hittites, marked the end of the Mitanni kingdom as a major power. The Hittites subsequently installed Shattiwaza to rule Mitanni and further their own political objectives.

The marriage between Tadukhepa and Amenhotep III, initially intended to solidify a peaceful alliance, ultimately became entangled in a complex web of regional politics and military conflict. The episode underscores the precarious nature of power dynamics in the ancient Middle East, where diplomacy and dynastic marriages could be swiftly overshadowed by the realities of war and conquest.

From Hittite Vassal to Assyrian Vassal

The Hittite King Suppiluliuma I (c 1344-1322 BC) divided the Mitanni heartland, establishing provinces with capitals in Aleppo and Carchemish. While some degree of autonomy remained, Mitanni became a Hittite vassal state referred to as "Hanigalbat."

The exact timing of Mitanni's absorption into the Assyrian empire remains unclear. It likely occurred sometime between the reigns of Hittite king Mursili II (1321-1295 BC) and Tudhaliya IV (1246-1215 BC) during whose reign, the Battle of Nihriya in 1245 BCE, signalled the beginning of the end of the Hittite Empire.

Mitanni's decline accelerated with the rise of the Assyrian Empire. Assyrian inscriptions by King Adad-nirari I (c 1307-1275 BC) boast of defeating a Mitanni king, Shattuara I, who challenged Assyrian might. This victory forced Mitanni to swear allegiance to Assyria, transforming it from an equal power to a tributary state.

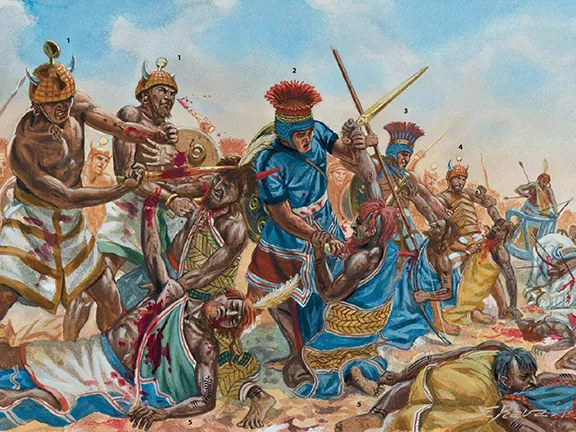

Further weakening Mitanni was King Shattuara II's rebellion around 1250 BC. Supported by the nomadic Ahlamu tribe, Shattuara attempted to throw off Assyrian control. Despite employing strategic tactics to disrupt Assyrian supply lines, Shattuara's forces were ultimately crushed by Shalmaneser I (c 1270s-1240s BCE), Adad-nirari I's son.

Shalmaneser's inscriptions boast of a brutal victory, claiming the slaughter of 14,400 enemy soldiers and the enslavement of many more. Major cities and fortifications were razed, with the conquest extending from Taidu (northern Iraq) to Irridu (Syria), encompassing the Mount Kashiyari range in modern-day Turkiye. His inscriptions mention the conquest of nine fortified temples, 180 Hurrian cities were "turned into rubble mounds" and Shalmaneser "'slaughtered like sheep the armies of the Hittites and the Ahlamu his allies'"

This devastating campaign effectively crippled Mitanni.

The final blow came at the Battle of Nihriya (1245 BC). Shalmaneser's son, Tukulti-Ninurta I (c 1244-1208 BC), decisively defeated the Hittites, ending their control over the region. With this victory, Assyria fully absorbed the remnants of the once-powerful Mitanni kingdom.

Why did the Bronze Age Kingdom of Mitanni Collapse?

The Kingdom of Mitanni fell from a major power to oblivion due to a combination of internal conflict, external pressures, and strategic manoeuvring by rival empires.

Internal Conflict: A power struggle within the Mitanni royal family weakened the kingdom, making it vulnerable to external attacks.

Hittite Rivalry: The Hittites saw an opportunity to disrupt Mitanni's control over trade routes and backed a rival claimant to the throne, ultimately conquering the Mitanni capital and reducing it to a vassal state. Their secondary objective was to obtain a foothold on the north eastern Mediterranean coast together with the emerging trading port of Ugarit

Assyrian Rise: The growing power of the Assyrian Empire further squeezed Mitanni. Assyrian victories forced the kingdom to become a tributary state, followed by a brutal campaign that crippled its remaining strength.

Loss of Egyptian Support: Whilst initially backing Mitanni against the Hittites, by about 1340 BC, Egypt's position in the northern extremes of its vassal city states in Syria was no longer tenable. Supply lines were long, over 1200 kilometres. Both the Hittites and Assyrians were battling over control of the Mitanni city states and Egypt could see no reason to be caught in the middle. Egypt's presence in the area gradually diminished leaving Mitanni to its fate.

These factors combined to dismantle Mitanni's power structure and eventually lead to its complete absorption by the Assyrian Empire.

Factors not contributing to the collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

The Kingdom of Mitanni had already been absorbed into the Hittite and Assyrian Empires by the onset of drought in the area, recorded as starting about 1250 BC.

There is no record of any natural disasters such as earthquakes during this period. Recently, archaeoseismologists have found evidence of an 'earthquake storm', a series of earthquakes, that afflicted the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, between 1225 BC and 1175 BC, too late to have affected the Kingdom of Mitanni.

Although there was undoubtedly conflict between the members of the royal family, there is no evidence that this spread into a general uprising with the population taking one side or the other.

Throughout the period of the Kingdom of Mitanni, it seems that food production was not a problem in the fertile lands of the kingdom. Starvation and subsequent depopulation of urban centres and migration of the population was not a factor in the kingdom's demise. In fact, the bountiful land may well have been one reason the region was so desired by the Hittites and Assyrians.

Mitanni, Hittites, and Assyrians

Due to the interconnectedness of the Kingdom of Mitanni, the Hittite Empire and the Middle Assyrian Empire, you will find many mentions of Mitanni in the articles that deal with the demise of the latter two.

References

Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004), p.154

Durant, W. Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Kantor, H. J. "Mitanni." Oriental Institute of Chicago, Plant Ornament in the Ancient Near East, Ch. XIV, pp. 1-42.

Kriwaczek, P. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. St. Martin's Griffin, 2012.

Leick, G. The A to Z of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press, 2010.

Mark, Joshua J.. "Mitanni." World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 29 Nov 2021. Web. 19 Jul 2024.

Pritchard, J. B. The Ancient Near East, Volume I: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Van De Mieroop, M. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC. Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Image Credit

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron