Civilisations that Collapsed

The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

The story of the demise of the Hittite New Kingdom (1400-1200 BC), also known as the Hittite Empire, really starts with the reign of King Suppiluliuma I who took the throne between 1380 and 1375 BC.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-09-18 | Last Updated 2025-11-20 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 702 times

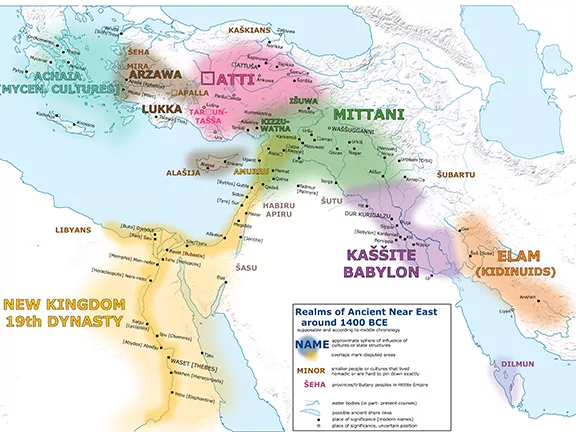

The Hittite Empire about 1300 BC

Suppiluliuma I: A Powerful Hittite Ruler

While the exact dates of his reign are debated, Hittite king Suppiluliuma I played a significant role in shaping the 14th century BC Middle East. Early estimates placed his rise to power around 1380 BC, followed by a reign lasting roughly four decades.

The early part of Suppiluliuma's rule focused on strengthening the Hittite heartland. He bolstered Hattusa's defences, constructing expansive city walls that enclosed a substantial area exceeding 120 hectares. Additionally, the Hittite Empire witnessed territorial expansion towards the southeast, with most northern Syrian cities bowing to Suppiluliuma's authority.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Suppiluliuma's Expansion at the Expense of Mitanni

King Suppiluliuma's reign witnessed a significant shift in power in the region. The once-mighty Mitanni kingdom was reduced to a vassal state of the Hittites.

Exploiting Mitanni Weakness

The Amarna Letters, a collection of diplomatic correspondence, reveal communication between Suppiluliuma and Egyptian pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. Notably, one letter from Suppiluliuma pertains to Mitanni. Egypt's previous alliance with Mitanni had waned under Amenhotep III. This withdrawal of support left Mitanni vulnerable, allowing Suppiluliuma to exploit the situation to his advantage.

Reshaping the Region

Following Mitanni's decline, Suppiluliuma established two new Hittite provinces: Aleppo and Carchemish. He strategically distributed much of the former Mitanni territory among his allies. The remaining portion retained a degree of autonomy but became a Hittite vassal state known as Hanigalbat.

Suppiluliuma I, capitalizing on a weakened Mitanni, flexed his military muscle. He conquered Syria and backed a rival claimant to the Mitanni throne. This strategic move forced Egypt, wary of the Hittite army's rising power, to abandon their support for the Mitanni king, Tushratta.

Taking advantage of Egypt's political turmoil under Pharaoh Akhenaten, Suppiluliuma I launched a successful expansion. He effortlessly annexed kingdoms and vassal states previously under Egyptian control, such as Byblos. About sixty of the Amarna letters document Egyptian diplomatic efforts to keep the kings of Byblos, Rib-Hadda and his successor Ili-Rapih, loyal. The extent to which Byblos was then influenced or controlled by the Hittites is still a matter of debate. The letters also indicate that the Habiru, a miscellaneous group of outlaws, rebels, and mercenaries who roamed the Fertile Crescent at this time, were raiding neighbouring city states.

Akhenaten's death offered further opportunity. The new Pharaoh, Tutankhamun, attempted to halt the Hittite advance by dispatching General Horemheb. However, these efforts proved largely futile. The Hittite army, honed through recent conquests, had significantly outpaced the declining Egyptian forces.

A Suspicious Request

Following the unexpected death of Pharaoh Tutankhamun in 1327 BC, his queen Ankhsenamun made a bold move. In a break from tradition, she sent a plea to Hittite King Suppiluliuma I. Ankhsenamun feared ruling alone and apparently lacked a suitable heir. She requested one of the king's sons as a husband, emphasizing her unwillingness to marry a lesser official.

This unprecedented request from an Egyptian queen understandably caused suspicion. Suppiluliuma I confirmed its authenticity before sending his son Zananza to Egypt for a potential marriage and ascension to the throne.

A Deadly Plot

Tragically, Zananza never reached Egypt. He was murdered, most likely by rivals within the Egyptian court, possibly the ambitious general Horemheb or the powerful vizier Ay. Their motive? To prevent a foreign prince from claiming the Egyptian throne that they coveted themselves.

Escalating Conflict

The murder of Zananza inflamed tensions between Egypt and the Hittites. Suppiluliuma I intensified his military campaigns, focusing more directly on conquering the remaining territories of the Levant, further straining relations between the two empires.

A devastating plague swept through the region in 1322 BC, claiming the life of Hittite king Suppiluliuma I. The prevailing theory suggests the illness arrived with Egyptian captives he brought back from his conquests. This tragedy resulted in a rapid succession. Arnuwanda II, the heir groomed for the throne, also succumbed to the plague. The crown then passed to his younger brother, Mursilli II.

Mursilli II's youth and lack of experience led the surrounding rulers to underestimate him. However, as history would reveal, this was a grave miscalculation.

Mursili II Faces Revolt: Securing the Hittite Throne

Mursili II's rise to the Hittite throne was far from smooth. Rebellions flared across Anatolia, threatening the new king's authority. Uhha-Ziti, king of Arzawa Minor, emerged as a key figure in this resistance. He provided sanctuary to anti-Hittite rebels and garnered support from Manapa-Tarhunta of the Seha River Land and even the king of the powerful Ahhiyawa (Mycenae). However, not all Arzawan kingdoms sided with Uhha-Ziti. King Mashuiluwa of Mira remained loyal to the Hittites, creating a division within Arzawa.

Despite facing an outbreak of disease within their own ranks, Mursili launched a military campaign to quell the rebellion. The siege of Apasa, the Arzawan capital, proved decisive. Uhha-Ziti and his family were forced to flee to Mycenaean-controlled territory, effectively crippling Arzawa's power. This victory solidified Mursili II's position and marked a turning point in Hittite dominance over Anatolia.

Mursili II: Expanding the Hittite Empire

By the reign's peak around 1300 BC, the Hittite Empire under Mursili II reached its greatest extent. It stretched westward to Arzawa and eastward to Mitanni, encompassing vast territories. The north included Kaska lands and extended as far as Hayasa-Azzi in the northeast. The empire's southern reach touched Canaan near the southern Lebanese border.

Mursili II's 25-year reign ended with his death, leaving the throne to his son Muwatalli II (1295-1272 BC). Muwatalli II immediately faced a pressing issue: a figure named Piyamaradu (or Piyama-Radu) who presented an ongoing challenge.

Piyamaradu's Challenge to Hittite Authority

Piyamaradu, a figure of controversy, emerges from historical records as a thorn in the side of the Hittite Empire for over three decades during the reign of at least two Hittite kings: Muwatalli II and Hattusili III. Described as a 'rebellious Hittite dignitary,' he persistently instigated unrest in Hittite vassal states across western Anatolia. His ultimate goal appears to have been the restoration of his dynastic claim to the throne of Arzawa, a region heavily influenced by the Hittites and recently the scene of a failed revolt.

Piyamaradu's strategy involved launching attacks and raids on various Hittite vassal states, including Arzawa, Seha, Lazpa (present-day Lesbos), and Wilusa (commonly identified as Troy). However, his efforts to undermine Hittite control proved unsuccessful.

Following setbacks at the hands of the Hittite "Great King," Piyamaradu sought an alliance with the Ahhiyawa (Mycenaeans) through a strategic marriage. He married his daughter to Atpa, the Mycenaean vassal king of Miletus.

Our primary source for these events comes from the Manapa-Tarhunta letter, written around 1295 BC. Manapa-Tarhunta, king of the Seha River Land, a Hittite vassal state south of Wilusa, addressed this letter to the Hittite king, likely Muwatalli II. The letter details Piyamaradu's assault on Seha and his installation of Atpa as a rival ruler. The letter informs Muwatalli that "[At the moment] everything is fine", that Hittite troops had arrived in Seha, established order, and then moved on to Wilusa (pretty well confirmed as the city of Troy) in northwest Anatolia suggesting the relief of Seha and Wilusa were part of a broader campaign to quell rebellions.

The Alaksandu Treaty: A Pact Between Muwatalli II and Wilusa

A 1280 BC treaty, known as the Alaksandu Treaty, reveals a mutual defence pact between the Hittite Empire and the city-state of Wilusa. King Muwatalli II of the Hittites and Alaksandu of Wilusa signed the agreement.

An excerpt from the treaty reads:

'And as I, My Majesty, protected you, Alaksandu, in good will because of the word of your father, and came to your aid, and killed your enemy for you, later in the future my sons and my grandsons will certainly protect your descendants for you, to the first and second generation. If some enemy arises for you, I will not abandon you, just as I have not now abandoned you. I will kill your enemy for you.'

This passage suggests a history of Hittite intervention on Wilusa's behalf.

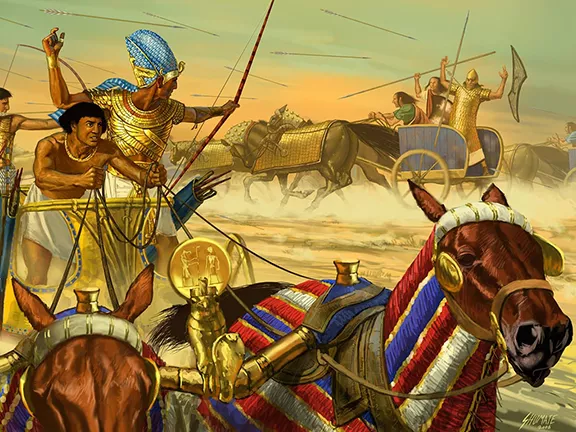

Testing the Pact: The Battle of Kadesh

Around 1274 BC, the pact faced its first major test. The Hittite army, including Wilusa's forces alongside other allies, clashed with the Egyptians at the Battle of Kadesh.

Estimates of Muwatalli II's army at Kadesh vary depending on the source (Hittite or Egyptian). Regardless of the precise numbers, it is clear Muwatalli mobilized a significant force fielding an army of between 23,000 and 50,000 troops, including between 2,500 and 10,500 chariots, and enlisted support from distant Hittite vassal states like Pitassa, the Seha River Land, Wilusa, Carchemish, Mitanni, Ugarit, Aleppo, and even Kadesh itself.

After Muwatalli II

Following the reign of Muwatalli II (c. 1295 to1272 BC), his son Mursilli III ascended the Hittite throne. However, his rule was short-lived, lasting only five years. During this period, a significant event occurred: the Assyrians conquered the kingdom of ?anigalbat, securing control of the eastern bank of the Euphrates River.

Mursilli III's reign was cut short by his uncle, Hatusilli III, who was Muwatalli II's brother. Hatusilli III is most famous for his role in establishing the world's first known peace treaty, the Treaty of Kadesh, with the Egyptians in 1258 BC, sixteen years after the epic battle between the two empires.

Piyamaradu's Flight and the Tawagalawa Letter

In the mid 13th century, Piyamaradu resurfaced as a source of trouble for the Hittite king. Having incited a failed rebellion in Lukka, he sought refuge in territory controlled by the Ahhiyawa. This prompted the Hittite king, probably Hattusili III, to compose a letter, known as the Tawagalawa Letter, addressed to the Ahhiyawa king. The letter addressed not only the issue of Piyamaradu seeking asylum but also a disagreement regarding Wilusa.

A 13th Century BC Plea for Cooperation: The Hittite Letter to Ahhiyawa

Dating back to around 1250 BC, a fragmentary clay tablet sheds light on the diplomatic relationship between the Hittite Empire and the enigmatic kingdom of Ahhiyawa. Often referred to as the "Tawagalawa Letter" due to a possible reference to a location or individual, the tablet offers a glimpse into a request for cooperation from a Hittite king.

The exact identity of the Hittite author remains debated, with Hattusili III being the most likely candidate. The letter is addressed to an unnamed Ahhiyawan king, potentially delivered through a Hittite official or individual named Tawagalawa. This Tawagalawa appears to be stationed in western Anatolia, possibly recruiting mercenaries hostile to the Hittites.

The core message revolves around suppressing anti-Hittite activities in the region, particularly those of a rebel named Piyamaradu. The Hittite king presents the Ahhiyawan king with three options: extraditing Piyamaradu, expelling him from Ahhiyawa, or offering him asylum with the condition of refraining from further rebellion.

The respectful tone suggests the Hittite king viewed his Ahhiyawan counterpart as an equal, addressing him as "brother." This aligns with the concept of diplomacy between Bronze Age empires, where maintaining alliances and managing potential conflicts were crucial aspects of statecraft.

The letter goes on to refer to previous disputes over Wilusa which had now been settled amicably,

'Oh, my brother, write to him this one thing, if nothing else: '...the king of Hatti has persuaded me about the matter of the land of Wilusa concerning which he and I were hostile to one another, and we have made peace.'

And later.

'And concerning the matter (of Wilusa), about which we were hostile (because we have made peace) what then?

Hittite Succession and Assyrian Challenge

Following the death of Hatusilli III in 1245 BC, his son Tudhaliya IV ascended the Hittite throne. This period coincided with the rise of Assyria as a regional power. The Assyrians began to challenge Hittite dominance over territories previously controlled by the Mitanni empire.

Tudhaliya's Conquest of Alashiya (Cyprus)

King Tudhaliya launched a military campaign against Alashiya soon after taking the throne. The exact reasons behind the invasion remain unclear, but securing control of the island's rich copper resources might have been a key factor. A statue dedicated to Tudhaliya boasts of his victory, claiming he captured the king of Alashiya (Alashiya) along with his family and seized a vast amount of wealth, including silver, gold, and prisoners. The inscription further states that he subjugated Alashiya and imposed tribute:

'I seized the king of Alashiya with his wives, his children'. All the goods, including silver and gold, and all the captured people I removed and brought home to Hattusa. I enslaved the country of Alashiya and made it tributary on the spot.

The Clash at Nihriya: A Turning Point for the Hittite Empire

Following the rise of ?attusili III to the Hittite throne, the kingdom had already ceded control of the former vassal state of ?anigalbat to the Assyrians. This loss undoubtedly rankled with father and son.

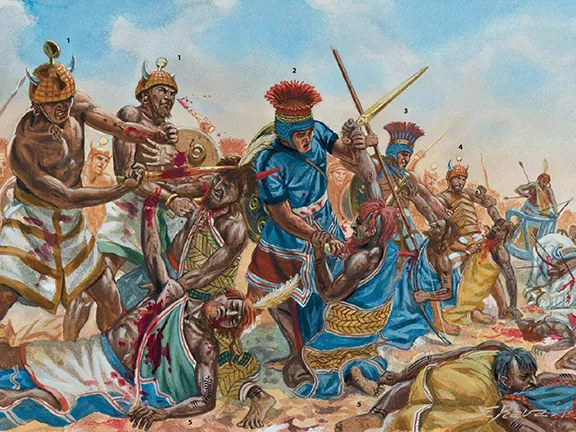

Tensions escalated further when Assyrian king Sulmanu-asared I expanded his influence in Syria, a region the Hittites considered within their sphere of power. This perceived encroachment culminated in a major battle near Nihriya around 1245 BC.

King Tud?alia IV, ?attusili's son and successor, led the Hittite forces against the Assyrians. However, the Hittites were defeated at Nihriya located in the Upper Balikh region in Turkiye. The remnants of the Mitanni Empire thereafter came under Assyrian rule.

The Milawata Letter: A Request for Restoration

The Milawata Letter, sent around 1240 BC, is a diplomatic message from Hittite king Tudhaliya IV to a western Anatolian vassal state, possibly the Kingdom of Mira.

Following the exploits of Piyamaradu, the Hittite text reveals a new ruler named Walmu on the throne of Wilusa, another Hittite vassal. Unidentified individuals, possibly linked to the Mycenaeans, had apparently overthrown Walmu, who sought refuge in another Hittite-allied kingdom.

The letter from Tudhaliya IV requests Walmu's return to Hattusa, the Hittite capital, for reinstatement as Wilusa's king. It assures the recipient, likely the king of Mira, of continued control over the region's city-states. The language used towards Ahhiyawa, the Mycenaeans, suggests their perceived decline in power compared to just a decade prior, when they were considered equals.

Tudhaliya IV's reign was followed by his sons, Arnuwanda III for a brief period, and then Suppiluliuma II in 1207 BC.

Suppiluliuma II the last king of the Hittite Empire

Suppiluliuma II ascended the Hittite throne around 1207 BC after his elder brother Arnuwanda III. To solidify his claim, he demanded oaths of loyalty from his court and subjects, emphasizing his respect for his deceased brother. Existing texts suggest there may have been internal conflicts within the royal family, hinting at potential challenges to his rule.

Suppiluliuma II inherited a kingdom facing difficulties both internally and externally. Diplomatic records reveal tensions with vassal states. A royal official wrote to the king of Ugarit criticizing his lack of respect for Suppiluliuma II. Additionally, the king of Carchemish, Talmi-Tessub, a Hittite royal family member, required a new treaty to confirm his loyalty and oversee Syrian affairs.

Suppiluliuma II corresponded with the Assyrian king, probably Tukulti-Ninurta I, though details are unclear due to damaged tablets.

Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions record Suppiluliuma II's military campaigns against former vassal Tar?untassa and the island of Alasiya (Alashiya).

Reliefs and inscriptions from Hattusa depict the king's conquests in southwestern Anatolia, including Wiyanawanda, Tamina, Maja, Lukka, and Ikuna. He then defeated and annexed the rebellious city of Tartuntassa. This focus on regaining control over southern Anatolia might have been driven by a potential famine in the region, evidenced by grain shipments from Egypt and Mukis.

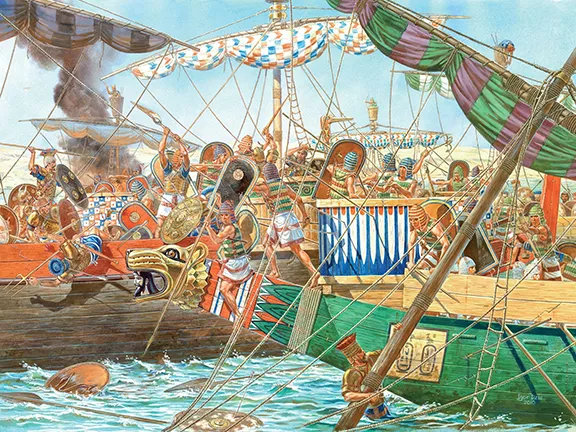

Naval Battles

Following his father's invasion of Alashiya, Suppiluliuma II led a naval fleet to victory against either the Cypriots or the "Sea Peoples" who had established a presence there. This event is considered the first recorded naval battle. Some historians believe Ugarit may have provided ships for this and subsequent Cypriot victories. Others have wondered why Suppiluliuma II felt the need to invade Alashiya again after his father, Tudhaliya IV, had reduced Alashiya to a Hittite vassal state about thirty years earlier. A clue may be seen in Suppiluliuma's account of his battle that first re-iterates his father's subjugation of Alashiya, re-enforcing the Hittite rights to Alashiya, followed by his own words:

'I Suppiluliuma, Great King, quickly embarked upon the sea. The ships of Alashiya met me in battle three times. I eliminated them. I captured the ships and set then afire at sea. When I reached dry land once more, then the enemy from the land of Alashiya came against me in droves. I fought them.'

Notice Suppiluliuma does not specifically say the enemy were Alashiyans.

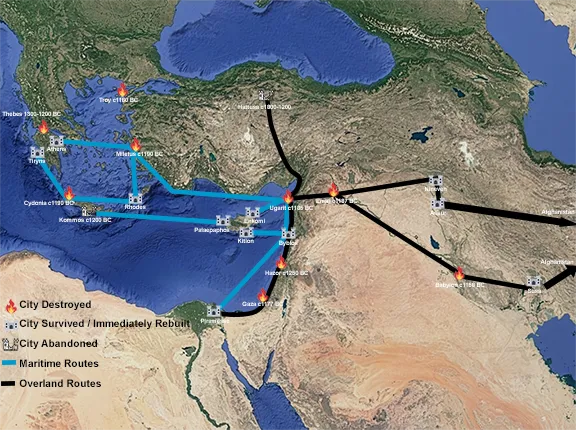

The Rise of the Sea Peoples

The "Sea Peoples" were migrating along the Mediterranean coastline, potentially disrupting Hittite trade routes. Apparently starting from the Aegean, and continuing all the way to Canaan, some of the Sea Peoples settled in Philistia and at Dor. In the process, they seem to have taken Cilicia and Alashiya from the Hittites, cutting off their coveted trade routes. Records from Ugarit mention a western threat, with the king requesting urgent military assistance from Ugarit.

"The enemy [advances] against us and there is no number [...]. Our number is pure(?) [. . .] Whatever is available, look for it and send it to me."

The Fate of Suppiluliuma II and the Hittite Empire

Suppiluliuma II's ultimate fate remains unclear. He may have abandoned Hattusa, contributing to the decline of the Hittite kingdom. While some sources suggest he died during the sack of Hattusa, others believe he relocated his court elsewhere. The Hittite Empire never recovered, and Hattusa was eventually destroyed by fire. Carchemish's ruler, Kuzi-Tessub, a descendant of Suppiluliuma I, would later claim the title of "Great King" around 1180 BC.

The apogee of Hittite power came under king Suppiluliuma I when his armies competed with Egypt and Mitanni for control of the Levant. The Hittite empire collapsed around 1200 BC, dissolving south of the Taurus Mountains into powerful Neo-Hittite city-states which were absorbed into the Assyrian empire in the ninth century BC.

Despite Assyrian dominance, the region retained the name "land of the Hatti" until around 630 BC. However, by that time, the Hittite people, their language, and the accomplishments of their kings had faded from memory. The Assyrians may have absorbed or displaced the Hittite population, leaving behind a cultural landscape forever altered.

Why did the Bronze Age Hittite Empire Collapse?

The Hittite Empire collapse should more accurately be described as a slow disintegration between its peak, about 1330 BC under Mursili II and about 1200 BC when the remaining empire splintered into independent city-states.

Internal Threats: Despite their undoubted success at initially subjugating city-states on the periphery of an expanding empire, the Hittites did not consolidate their gains by imposing strict control, probably due to a lack of manpower. This weakness allowed rebels such as Piyamaradu to incite rebellion. Rebellions in western and southwestern Anatolia were a constant drain on Hittite resources after about 1300 BC.

External Threats: The Hittite Empire was surrounded by other emerging kingdoms and empires. To the south were the Egyptian controlled city states of the Levant. To the east was the ambitiously expanding Middle Assyrian Empire. To the west were the Ahhiyawa (Mycenaeans) who seemed determined to expand their beach heads on the western Anatolian coast.

The decisive victory of the Assyrians at the battle of Nihriya (about 1245 BC) is often said to mark the beginning of the decline of the once mighty Hittite Empire. However, the outcome of the battle may have been very different if the Hittite Empire had not its resources consistently depleted by rebellions in its supposedly vassal city states in Anatolia.

The Sea Peoples: The question of who the Sea Peoples where or where they came from is, to a certain point, irrelevant here. There are too many accounts of invaders or foreigners arriving in the eastern Mediterranean, in the Hittite and Egyptian territories and extending down through the Canaanite city states, for the presence of a group of people, travelling by land and sea, sometimes bent on destruction, at other times only interested in resettling and merging with existing communities, for their disrupting presence to be ignored.

Over Extending: The Treaty of Kadesh in 1258 BC created an uneasy peace between the Hittites and Egyptians but antagonism between the two powers never disappeared. The Hittite invasions of Cyprus somewhere around 1245 and 1200 BC must have galled Egypt who considered Cyprus part of their domain. In any case, the later invasion of Cyprus occurred at a time when Suppiluliuma II's resources were already stretched dealing with internal rebellions and threats from the Assyrians. It was an ill advised third front unless Suppiluliuma was not attacking the Cypriots per se, but was attempting to displace the Sea Peoples who may have already subjugated Cyprus by that time.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron