Civilisations that Collapsed

The Rise of Bronze Age Empires alongside Trading Networks

When considering the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Near East, historians tend to neglect the role of a group of people who had emerged over a period of a thousand years into a significant power in their own right, the maritime traders and the merchants who operated and controlled the overland routes.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-04-27 | Last Updated 2025-11-22 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 5,732 times

Bronze Age Warfare: screenshot from the real-time battles in the video game A Total War Saga: Troy

The Palace-Temple Economy Model

A palace economy is a centralised economic system where a sizeable portion of wealth is controlled by a governing authority, often a monarch or priestly class. This central body, referred to as the "palace," redistributes resources to the population, which may rely heavily on this distribution. Historically, this system was justified by the belief that the palace was best equipped to efficiently allocate resources for the benefit of the society. A similar concept is the temple-state economy.

Essentially, a palace economy involves centralised planning and control. The governing body determines production, assigns labour, collects output, and redistributes it. This system often operates within a physical complex, such as a palace or temple, where economic activities are concentrated.

Accumulating Wealth and Power

While ostensibly serving the population, the palace's primary goal is typically to accumulate wealth and power. This wealth can be used for various purposes, including trade, investment in infrastructure, military expansion, and diplomatic alliances.

Through Servitude

In many ancient palace economies, the workforce was tied to the palace through servitude or patronage. The palace provided basic necessities like food, clothing, and shelter in exchange for labour. Economic growth often relied on military conquest, with plunder and captured labour contributing to the palace's resources.

And Warfare

All Bronze Age elites realized the downsides of warfare. Warfare is a non-productive policy, costly to both the aggressor and defender in terms of materials, resources, and manpower. The aims of a Bronze Age aggressor were base, to increase their wealth and stock of necessities by plundering the defender. Their secondary aim was to increase their population tax base by taking captives or taking control of a population centre along with its rural outskirts. In the latter case, warfare often resulted in a decimated city and a ruined hinterland lacking sufficient urban or rural population to rejuvenate itself. Each city state and later, empire or kingdom, had to maintain a defence force of one form or another, to deter and, when necessary, defend, the homeland, itself a huge expense.

And Trade

The only way to bring new wealth to an area, as opposed to recirculating existing wealth through hostile acquisition, was through the mechanism of trade. In order to trade, a palace temple had to produce a surplus of something that it could then exchange for goods it either needed, or exotic items that would enhance the status of the elite (and to a lesser extent, the producers) or be used for further trade and exchange.

All the early palace temples began life as nexus of trade, market towns in effect, situated at strategic locations. Some developed into city states and then further to full palace temples.

Emerging Merchant Class

The merchant class became an essential component of these urban centres. It was they who organised the trade of goods from far off places, arranged the finance to conduct that trade, communicated with trusted partners across the known world, transported the products and arranged for the sale or exchange at either end of the road.

The merchant trader, by necessity, was cosmopolitan, able to transact business across many city states, palace temples, kingdoms and empires some of which, at times, were hostile to each other. They became almost a nation unto themselves, an invisible force without which the Bronze Age empires and kingdoms could not have been built.

The Impact of the 4.2k yr BP Drying Event

It is noticeable that early palace temples were more altruistic than later and the boundary between the two can roughly be equated to the onset of the 4.2k yr. BP drying event, that affected many parts of the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East for between two and three hundred years, centred on 2200 BC.

The days of elites storing food during the good times and distributing it to those in need during the tough times disappeared. The 'modern' palace was an extractive institution that gained its wealth from taxes on trade goods, agricultural products, estates, compulsory labour, and turning raw materials into desirable commodities for export.

Some Bronze Age rulers found it expedient to gather wealth through raids on neighbouring city states and later, palace-temples and later still the kingdoms and empires that had evolved. The booty so gained would frequently include captives, particularly skilled craftspeople, as well as foodstuffs and the usual precious metals and stones.

Growth of Urban Communities

The urban communities that grew around these elite figures tended to concentrate on the plains and steppes. They depended on the pastoral communities that lay beyond in the surrounding hills and mountains for milk products and wool. Some of these lowland communities grew to become cities covering a hundred hectares with populations well into five figures but the norm was a medium to small town with a few thousand inhabitants and a correspondingly smaller administrative centre. Some of the cities were located near a coast and had a port within their orbits, a scenario that became synonymous with the Mediterranean.

And Palace Temples

In a remarkably short space of time these urban centres sprouted palaces and, to affirm the link between the ruling elite and the gods, temples. Palace-temples in the largest cities could be as large as a small village.

Inflationary Influences

The palaces and temples became 'sink holes' for necessities as well as incoming wealth. The accumulation and storage of precious raw materials created an inflationary demand for those materials and the deposition of the same materials in elaborate elite graves removed them from circulation altogether, thus perpetuating the inflationary cycle.

The First Entrepreneurs

Although the palace-temple system was autocratic, the rule of the elites was not total. Away from the city hub there was still room for entrepreneurial activity, some of which was taxed, but much of which went on below the radar, just the sort of environment an entrepreneurial merchant can exploit. Barter on a local scale ensured the survival of the peasant farmers.

Ebla was an early palace temple of which we know quite a bit due to the recovery of 17,000 cuneiform tablets dated to between 2400 BC and 2300 BC.

The Palace-Temple Economy of Ebla 3500 BC to 1600 BC

Ebla was one of the earliest kingdoms in Syria and was situated about 55 kilometres southwest of present day Allepo. Ebla became an important trade centre and its kingdom, gained by conquest or purchase of surrounding autonomous towns and villages, and strategically arranged marriages, eventually covered an area of 10,000 square kilometres, larger than even the Nile Delta or Cyprus. The Kingdom of Ebla included more than sixty vassal kingdoms and city-states, including Hazuwan, Burman, Emar, Halabitu and Salbatu.

The first Eblaite kingdom has been described as the first recorded world power (Samuel Finer and Karl Moore), and reached its peak about 2340 BC. It was bounded to the west by coastal city states, to the south by small city states along the Orontes river, and to the north and east by Mari and other major polities on the Euphrates.

The Ebla Tablets

During its partial excavation, over 17,000 cuneiform tablets, written in a local west Semitic language and Akkadian, cover the period 2400 BC to about 2300 BC. They record trade agreements, administration of the palace economy, politics and elite intermarriage with other polities.

The kings of Ebla had contacts with neighbouring kings, notably the powerful sovereigns of Mari and Nagar, and with the kings of more distant regions, like Kish in Mesopotamia and Hamazi in western Iran. Excavations at Ebla have uncovered the oldest example of a written peace treaty, the treaty between Ebla and Abarsal (this could be the same city-state as Aburru, mentioned in the Mari texts), as well as proof of matrimonial alliances between the local kings and certain of their allies.

From the tablets, it appears that the kings of Ebla allowed councils and assemblies to make policy decisions and that access to those councils was less constricted. The Ebla kings were also less powerful and self-glorifying in art and literature than their contemporaries. Similarly, the temples in Ebla, though substantial, were less grand than others in the Mesopotamian arena.

The economy of Ebla

The economy was based on large scale cereal farming with vines and olives on higher ground. The elite were not shy in awarding vast tracts of land to their supporters; one queen of Ebla is recorded as giving a priestess land with 16,320 units of olives, 8,800 units of sowable land, 630 units of vineyard.

Tens of thousands of sheep supplied wool to a textile industry mostly owned by the royal family and elites, altogether a few hundred people. Most of the products of industry were for export to other city states and polities, Mari was a major market for goods from Ebla, the remainder went to the elite, and filtered down through their retainers and servants. One of the perhaps unanticipated consequences was that the Ebla fashions of the time, dress and jewellery, took on a distinctly 'palace' look.

Daily activity in Ebla

The archives also give us a view of daily activities. At any one time, 800 women were weaving, grinding cereals and cooking, 500 smiths, 150 carpenters, 35 physicians, 30 musicians, and 14 barbers all supported by handouts from the palace.

Of silver and gold

But it was trade in metals that brought in the greatest rewards. Silver was the value standard at the time with gold at Ebla being worth between two and five times that of silver, and copper about one twentieth the value of silver.

According to the archives, forty-five kilograms of gold and between two hundred and fifty and four hundred and fifty kilogrammes of silver passed through the palace on an annual basis with the largest shipments being 1.5 tonnes. Some of the silver and gold came from the peasant farmers who were expected to pay their taxes in metallic form, a clear indication that primary products such as corn, and manufactured products such as textiles, had a relevant metallic value, but most silver and gold came from trade. Ebla played the metal commodities market and was advantageously placed between Egypt, Mesopotamia and Anatolia to do so. In Mesopotamia the value of silver to gold was 10:1 and in Egypt the ratio was 1:2 to 1:1.35.

Ebla became what is termed a 'palace-temple economy', an economic model that would become common across the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East.

Ebla in ruins

Between c 2400 BC and 2290 BC, Ebla was destroyed. There are various theories involving Sargon of Akkad, who took over Mari about the same time, Mari itself in revenge for an assault on them by Ebla between 2400 and 2300 BC, and a natural disaster that caused a fire in the palace about 2290 BC.

Ebla rises from the ashes

About 2200 BC, Ebla was rebuilt with new palaces, temples and fortifications. The first known king in this period was called Ibbit-Lim, an Amoritic name that may indicate Elba was occupied by Amorites who also occupied most of what is now Syria.

is reduced to a vassal state

By 1800 BC, Ebla was a vassal state of Yamhad, a small Amorite kingdom based in Allepo. Ebla maintained its trading connections, particularly with Egypt.

and fades into obscurity

Ebla's long history ended in c 1600 BC, when it was destroyed by the Hittite King Mursili I and faded into obscurity.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Ways of Horus

The Predynastic Egyptians meanwhile were forging trading links with the Levant. The early rulers of Predynastic Egypt soon realised that the funnel created by the Mediterranean - Gulf of Suez gap allowed them to regulate goods entering and leaving Egypt. By about 3100 BC, the Sinai passage had become formalised as a 340 kilometre, 10 day route, 'The Ways of Horus', that ran from the delta as far as modern day Tel Aviv. From about 2700 BC, the land route was supplemented by a coastal maritime route from the Nile delta to Ashkelon, Haifa and Byblos.

Copper, oils and wines entered Egypt from the Levant, whilst copper and turquoise came in from Sinai. The maritime route brought in bulk cargoes of Lebanese cedar, metals from Anatolia, rare stones and lapis lazuli. Egypt was blessed with huge deposits of gold in the eastern desert and in Nubia.

The Incense Road

At the same time around 3000 BC, the Egyptians started to develop the Incense Road trading for incense from the Arabian Peninsula.

The Salt Road

Another Egyptian initiative was the Salt Road and the Trans Sahara Trade Network. A network of routes between oases across the Sahara Desert to the cities in West Africa developed after 3000 BC. Trade goods were not confined to salt. Gold, slaves, textiles, and spices made the hazardous desert crossing.

City State of Dilmun - Early links to the East

About 3000 BC, the Sumerians established a trading post about halfway down the Persian Gulf at a place called Dilmun. Dilmun was celebrated for its wealth and was the 'land of milk and honey' according to ancient Sumerian creation myths. An archaeological site on the northern part of the island near Bahrain, is thought to be Dilmun.

What is remarkable about the site, apart from a treasure trove of Bronze Age artefacts, is that Dilmun had a population of about five thousand people, nurtured by numerous freshwater springs, now long dried up (interestingly, there are still freshwater springs nearby that emerge beneath the sea).

Cuneiform texts found in the temple of Inanna at Uruk record that, from about 2800 BC, small shipments of barley were arriving in Dilmun, bound for Magan. These shipments grew to several hundred tons per shipload by the end of the millennium.

The ships of Dilmun

About 2300 BC, king Ur-Nanshe of Lagash recorded that 'The ships of Dilmun brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands.'

Expanding influence

By 2050 BC, Dilmun was an independent city-state with contacts in Mari in the northern Levant as well as Mesopotamia. Fifty years later, Dilmun was almost the size of Ur, the largest Mesopotamian city at that time. Access to the sea was through a set of sea gates from a large central square at one end of which was a warehouse, probably what today we would call a customs house. Around the square would be piled up the produce brought from Ur, barley, dates, and Mesopotamian cloth. Under guard would be the valuable cargoes bound for Ur, ivory and copper ingots.

The Ur tablets

A large cache of tablets has been found in Ur that name one of the merchants involved in this trade who was active about 1800 BC, Ea-nasir, then the largest copper merchant in Ur.

One of the tablets records a shipment of twenty tonnes of copper. Another records the complaint of a customer by the name of Nanni: 'You said, I will give good ingots to Gimil-Sin. That is what you said, but you have not done so. You offered bad ingots to my messenger saying, 'Take it or leave it.' Who am I that you should treat me so? Are we not both gentlemen?'

Another tablet records an investment in one of these trading ventures. 'Two mina (120 shekels) of silver, which is valued at five gur of oil and thirty garments for an expedition to Dilmun to buy there copper for the partnership of (identified only as 'L' and 'N'). After safe termination of the voyage, you will not recognise commercial losses. The debtors have agreed to satisfy you with four mina of copper for each shekel of silver as a just price.'

Note that silver is by now the common medium of exchange rather than the value exchange of miscellaneous goods.

From Dilmun to the Indus Valley

Dilmun was only one trading post, albeit a very wealthy one, on the route to the Indian Ocean and the Indus valley civilisation in Pakistan. A cache of merchant seals of a type commonly used in the Indus valley turned up in the cities of Umma and Ur, in Mesopotamia and on the coast of the Arabian Peninsula. A large number of seals have also been found at the port of Lothal in western India.

Mesopotamian weights have been discovered in various cities in the Indus valley along with animal headed pins native to Mesopotamia. Clearly there was a great deal of interaction across the Indian Ocean. But were there colonies of trusted foreign merchants from the Indus valley permanently resident in Mesopotamia? The model for such trade diaspora was already in place in Anatolia who hosted the karum merchants of Assyria at about the same time. The presence of the very personal Indus valley seals might indicate that there were. No merchant could afford to lose his seals that alone guaranteed the quantity and quality of his trade goods.

From City-States to Empires: A Shift in Power

During the third millennium BC, southern Mesopotamia witnessed a gradual shift in power dynamics. Initially, city-states like Ebla, Uruk under Enshakushana and Umma under Lugal-zagesi achieved temporary dominance over their neighbours. The cluster of city-states in the floodplains of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers comprised the Sumerian civilisation. Around 2340 BC, Sargon of Akkad established the world's first empire, now known as the Akkadian Empire, uniting all Mesopotamian city-states and stretching its influence into eastern Syria.

The Rise of Rival Kingdoms and the Power Shift

The 2nd millennium BC witnessed a shift from a single dominant power to a more balanced international landscape. No single kingdom held absolute sway, paving the way for the emergence of several powerful and stable states. These new powers dominated their regions and held varying degrees of control over vassal states, though these allegiances often fluctuated over time. Rivalries between the dominant kingdoms frequently arose over the hegemony of these vassal states, sometimes erupting into open conflict.

Egyptian trading network

Meanwhile, Egypt was extending its trading network. From as early as 2500 BC, Egyptian ships sailed down the Red Sea, over 1500 kilometres, to the 'Land of Punt', modern Yemen and Somalia. From a wall painting in her mortuary sanctuary, we know that Queen Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt from 1479 to 1458 BC, ordered an expedition to Punt. Galleys, about eighty feet long and equipped with sails and oarsmen, were loaded with grain and bails of textiles for the outward journey and returned with, 'marvels of the country of Punt: all goodly fragrant woods of God's land, heaps of myrrh resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony, and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, khesyt wood, with ihmut incense, sonter incense, eye-cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of southern panther, with natives and their children. Never was brought the like of this for any king who had been since the beginning.'

The Amorite Era (2004-1595 BC)

The first half of the 2nd millennium BC was dominated by the Amorite kingdoms. These kingdoms, flourishing from 2004 to 1595 BC, established a kind of common ground for political practices across a vast region stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Zagros Mountains. Mesopotamia and Syria witnessed the rise and fall of several dominant kingdoms. Initially, Isin and Larsa, successors to the Ur Empire, held sway. However, Babylon eventually emerged as the dominant power under Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) and his successors, while Elam's attempts at regional dominance ultimately failed. In Syria, the kingdom of Yamhad (Aleppo) enjoyed a period of prominence, benefiting from the decline of its rivals Mari and Qatna during the 18th and 17th centuries BC.

The Rise of New Powers (17th-12th Centuries BC)

The Amorite period ended with the destruction by the Hittites of its two major kingdoms. The Hittites had consolidated their control over eastern Anatolia by the late 17th century BC. Concurrently, the Hurrians established increasingly powerful political entities, culminating in the formation of the Kingdom of Mitanni. These two emerging powers, along with Egypt, ushered in a new era characterized by larger, more powerful, and culturally diverse kingdoms. Several decades after the expulsion of the Hyksos between 1491 and 1480 BC, Egypt launched military campaigns into the Levant, expanding its empire until it bordered that of Mitanni.

A new Balance of Power

This shift marked a new balance of power. Most of the former Amorite kingdoms became vassals to these new dominant forces, with the notable exception of Babylon, which remained a significant power under the Kassite dynasty (1595-1155 BC). The rulers of these dominant kingdoms were considered "great kings" amongst themselves, operating on an equal footing. By the 14th century BC, Assyria had replaced Mitanni as one of these major powers. Elam, particularly during the 13th and 12th centuries BC, could also be considered a significant player on the international stage.

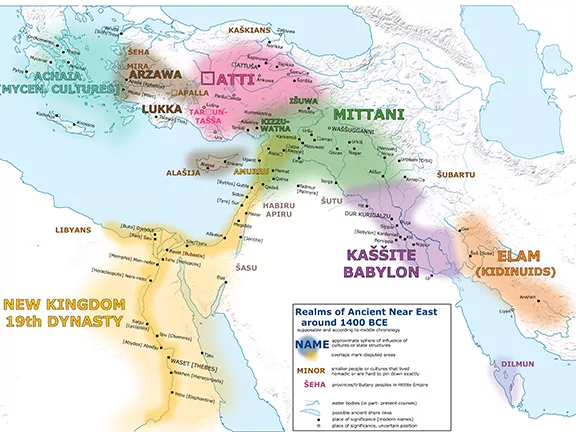

The Bronze Age Civilisations

Middle East about 1300 BC

By about 1300 BC, there were six major civilisations in the Middle East, the Mycenaean Civilisation, the Hittite Empire, the Middle Babylonian Kingdom, the Egyptian New Kingdom, the Kingdom of Mitanni, and the Middle Assyrian Kingdom. The Middle Elamite Kingdom would emerge later, about 1210 BC, by which time Mitanni had been subsumed into neighbouring civilisations.

In addition to the 'traditional' Bronze Age civilisations, we must also add Cyprus and the Canaanite city states because they played a pivotal role in the rise and fall of the recognised Bronze Age civilisations and the subsequent emergence of succeeding empires.

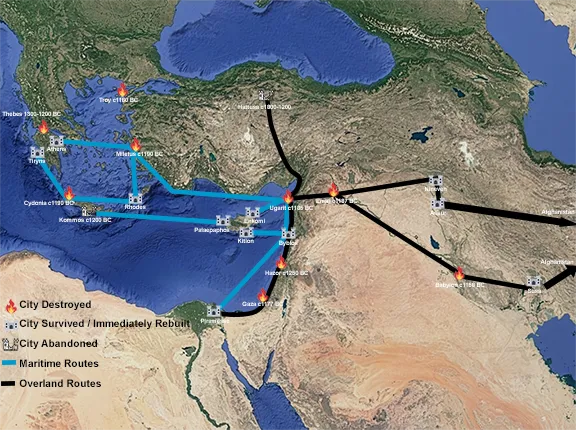

The Growth of the Trading Networks

All the bronze age ruling elite appreciated the negative impact of warfare to a greater or lesser extent. They developed interconnected trading networks that also functioned as channels for diplomacy. The coastal city-states provided the connection between the overland traders and the maritime merchants. Some of the city states housed colonists from other city states who functioned as freight forwarders and diplomatic missions on behalf of their mother polity, similar to foreign embassies and consulates found in major cities today.

These trading networks developed concurrently with the rise of the city states and the subsequent empires and kingdoms and were an integral part of that growth. One would not have happened without the other.

It was over these networks that people, ideas, news, knowledge, and commodities flowed. The networks help explain the synonymity of the physical structure and administration of the dozens of city states that were spread out across the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. Only when the networks broke down was warfare likely, at least in theory.

Who controlled the networks?

Although the states nominally controlled the networks, they were operated by merchants and traders and their representatives, some of whom were native to the state, some of whom were colonists. Many of these 'companies', such as those at Kultepe-Kanesh, operated under little palatial scrutiny and were able to accumulate lucrative profits.

The nature of the merchant

Merchants and traders are by nature peripatetic, moving around the land and seascape, crossing boundaries, by necessity multi-lingual, with allegiance primarily to themselves and their families. Over time these dominant individuals became less responsive to the control of the rulers whose territory they traversed or sailed between. The term 'port power' has been coined for this phenomenon at sea, perhaps 'company power' would suffice for this phenomenon on land.

The Mit Rahina Inscriptions c. 1900 BC

The amount of material that can be shown to have been imported that has been recovered by archaeologists from all the sites in the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, and all the cargoes recovered from shipwrecks by underwater archaeologists, must only be a tiny fraction of the total amount of trade goods going back and forth in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean.

The ancient Egyptian king Amenemhat II, who ruled between 1929 and 1895 BC, had two of his state sponsored expeditions recorded on a granite block that was later reused as a base for a statue of Ramesses II at Memphis. It is known as the Mit Rahina Inscription.

One military expedition to the north, records the destruction of two towns, Luai, and Lasy. The whereabouts of these towns is not known. The returning expedition brought back 1554 prisoners as well as furniture, precious stones and raw and worked metals. The prisoners were apparently put to work building a pyramid for Amenemhat.

A second expedition, this time mercantile, to the Levant consisted of two ships. They brought back 231 lengths of Lebanon cedar wood, 23 kilogrammes of silver, 133 kilogrammes of bronze, 435 kilogrammes of copper, 19 kilogrammes of white lead, 37 bronze daggers decorated with ivory, gold and silver, 225 kilogrammes of emery wood, 73 fig trees, and 537 kilogrammes of grinding sand, precious stones, oils and resins, and spices such as cinnamon and coriander. There is also mention of sixty-five humans. It is unclear whether they were part of an agreed exchange of captives or skilled workers.

The Kanesh Archive 1975 - 1880 BC and 1820 - 1750 BC

Donkey caravan

Just as the tonnage of freight in transit at sea at any one time was considerable, so too was that carried by overland caravans.

The Karum of Kultepe-Kanesh

Kultepe-Kanesh was a city state in the middle of Anatolia. The city contained a large Assyrian karum, or colony, that organised the Assyrian trading network in Anatolia. The karum was composed of families that hailed from Assur, some 775 kilometres away. There were over twenty such karums in Anatolia alone. Kultepe became a key centre of culture and commerce between Anatolia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. The private archives of the karum merchants have yielded 23,500 clay tablets and envelopes to date. There were two main phases to these operations, the first from about 1975 BC to about 1880 BC (from the reign of the Assyrian king Erishum I to that of Puzur-Ashur II), the second covering the period about 1820 BC to about 1750 BC.

The first Limited Company?

One tablet even details the formation of a 'limited company'. A merchant by the name of Amur Ishtar, oversaw the formation of an association between twelve merchants. The total fixed capital was 15 kilogrammes of gold that would be held for a period of twelve years. Profits from trading ventures were shared in a 1:3 ratio, one share to Amur, the rest divided between the merchants. A get out clause stipulated that, if a shareholder wanted to withdraw his capital before the end of the twelve years, he would receive 4 kilogrammes of silver for every kilogramme of gold invested. This tablet could be proof of the first company formation in the world?

All carried by donkey

The merchants ran donkey caravans trading gold and silver from Anatolia for textiles from Mesopotamia and tin from Uzbekistan. The caravans were enormous. One is recorded as consisting of 200 to 250 donkeys, each carrying sixty kilogrammes of metal or textiles. The journey took between thirty-five and forty days. It has been calculated that, over the seventy years covered by the records, over one hundred kilogrammes of silver and a thousand large, heavy textiles were moved annually.

It is interesting that tin was being exported into the Mediterranean area from Uzbekistan as early as 1920 BC. Clearly tin from Anatolia was not sufficient to meet increasing demand.

The Merchants of Ugarit 1200 - 1185 BC

Ugarit was a city state and port city in modern northern Syria about ten kilometres north of present day Latakia. It was established during the Neolithic period, began to emerge as a major trading centre about 1900 BC and reached its trading peak between 1500 BC and its destruction in 1185 BC. In 1928 AD, the Ugaritic texts were discovered by excavators of the ancient city. Approximately 1,500 texts written in Ugaritic, are dated to the late 13th century BC up until the day of the city's destruction. Other tablets found in the same location were written in other cuneiform languages including Sumerian, Hurrian, and Akkadian, as well as Egyptian and Luwian hieroglyphs, and Cypro-Minoan.

During the early 14th century BC, Ugarit was a vassal state of Egypt and, briefly, a vassal state of Mitanni. In about 1350 BC, Ugarit became a vassal city state in the Hittite Empire after Suppiluliuma conquered the area between 1350 and 1340 BC. Ugarit was administered by the Hittite viceroys in Karkemis until the Hittite Empire collapsed about 1180 BC, after which it was controlled directly from Karkemis.

Ugarit Texts

During the excavations at Ugarit, over 1,500 cuneiform tablets were found in the homes of the merchants of the city. We even know some of their names, Rasap-abu, and Rapanu, Urtenu who traded with Emar in northern Syria, Sinaranu whose ships went back and forth between Ugarit and Cyprus, and Yabninu, one of the more successful merchants, his house covered over one thousand square metres, who traded with Cyprus, the Aegean, the south Levantine coast and Egypt.

Urtenu was an agent in a commercial firm owned by the queen's son in law.

Rapanu was a scribe who communicated with the governor of Cyprus, the king of Carchemish and the Egyptian pharaoh.

The Ugaritic texts cover the period from about 1200 BC until the city's destruction in 1185 BC.

The droughts of 1250 and 1100 BC

From about 1250 to 1150 BC and 1100 to 950 BC, the entire region, including the Hittite Empire, the northern Levant, and the eastern Mediterranean, faced a drought that provoked crop failures. Ugarit received desperate pleas for assistance from other polities. One of the letters found in the House of Urtenu refers to a famine raging in Emar just before Emar was destroyed in 1185 BC. The letter was sent from Urtenu's representative in Emar, a man by the name of Banniya and reads, 'There is a famine in your (i.e. the company's) house; we will all die of hunger. If you do not arrive here quickly, we ourselves will die of hunger. You will not see a living soul from your land.'

We shall delve into this famine period in much greater depth when we look at the disintegration of the Bronze Age civilisations.

Proof of dybastic marriages

Leaving the last years of Ugarit aside for the moment, the Ugaritic texts tell us that the kings of Ugarit, of which we know all the names, married princesses from their neighbouring polity, Amurru, in dynastic marriages complete with dowries that were fit for a king.

Copper from Cyprus

One of the letters found in the House of Urtenu involves the importation of copper from Cyprus, "Thus Kushmeshusa, king of Alasiya [Cyprus], say to Niqmaddu, king of Ugarit, my son. All is well with me, my households, my countries, my wives, my sons, my troops, my horses, and my chariots. In exchange of the gift which you had sent me, I sent to you thirty-three (ingots of) copper; their weight is thirty talents and six-thousand and five-hundred shekels."

Apart from the financial details, this letter is the first mention ever of a king of Bronze Age Cyprus, Kushmeshusha.

From Ugarit to Mycenae

Two other letters, from the House of Rapanu, give us an insight into the Bronze Age world. The letters refer to two 'Hiyawa men' who were waiting in Lukka (now known as Lycia in southwestern Anatolia), for a ship from Ugarit. The letters were sent to Ammurapi, the last king of Ugarit, from the Hittite king, probably Suppiluliuma II. These are the first mentions of any connection between Ugarit and the Mycenaeans and the Aegean (Hiyawa).

Control of the Merchants of Ugarit

The Ugarit texts also give us a superb insight into the workings of the merchant system that depended, like its land-based predecessor at Kultepe-Kanesh some five hundred years previously, on raising capital, sharing the risk, stake sharing, and debt recovery mechanisms.

The various kings and queens of Ugarit were involved in planning and part funding potentially profitable mercantile ventures as well as the ceremonial exchanges between rulers briefly mentioned above. In effect the palace became a stake holder in a planned voyage with the remaining stakes being taken up by one or more merchants. The palace derived its profit from that made by the sale of its stake, plus a tax on the profits made by the merchants, paid in silver shekels or a part of the return journey's merchandise.

It was even possible for merchants to negotiate a royal favour. In one correspondence, we see the following text: 'Ammishtamru, son of Niqmepa, King of Ugarit, exempts Sinaruna [a merchant mentioned above], son of Siguna, his grain, his beer, his oil, to the palace he shall not deliver. His ship is exempt when it arrives from Crete.'

The standing of the merchants

The merchants were multi-talented with diverse other interests. Some held high office within the palace, some performed service as agents abroad, some were members of the chariot owning military elite, some were landowners growing cash crops for internal consumption and export, some operated transport services on behalf of the palace. The resemblance to a modern corporation intent on owning or at least controlling its own supply and delivery chains is remarkable.

The diverse range of trade goods flowing through Ugarit

The private archive of the merchant Yabninu, he of the extensive private mansion mentioned above, lists silver, tin (from the markets on the Euphrates river), iron, grain, oil, milk, wool, horses, fish, doves, tools, woods, reeds, walnuts together with shipments to ports all along the Levantine coast. Yabninu, and he was not alone in this, clearly had extensive, long range, connections.

The Ugarit merchants often travelled with their goods. Once outside the Ugaritic sphere of influence, and therefore protection, they became vulnerable to being robbed or even murdered by bandits and even, in at least one case, by an unfriendly king.

In addition to the Ugaritic merchants, we also see glimpses of foreign merchants in town. Some of them invested locally and were, at times, a disruptive influence. All were closely monitored.

Bronze Age Shipwrecks c 1335 and c 1200 BC

Reconstructed Cargo hold of the Uluburun

Two bronze age shipwrecks also illustrate not only the quantities of goods in transit by sea but also the diverse source of those goods. It is likely that both were sponsored by merchants rather than a state.

The Uluburun shipwreck

The Uluburun sank between 1335 and 1305 BC off the coast of Turkiye. The Uluburun ship was a merchant vessel that was carrying at least twenty tonnes of cargo on its final voyage. Take a deep breath.

The Uluburun cargo

In the hold was 10 tonnes of Cypriot copper in the form of 348 ox hide ingots together with 1 tonne of tin ingots from the Musiston mine in Uzbekistan and the Kestel mine in Anatolia, 150 Canaanite jars contained half a tonne of terebinth resin and oil, 350 kg of blue glass ingots from Egypt and an unknown quantity of fabric of which only a few red and purple threads remain, a consignment of elephant and hippopotamus tusks and carved ivories, blackwood or ebony from the Sudan, arrowheads, spearheads, maces, daggers, a lugged shaft-hole axe, four bronze swords (Canaanite, Mycenaean, and central Mediterranean types), a large number of tools included sickles, awls, drill bits, a saw, a pair of tongs, chisels, axes, a ploughshare, whetstones, and adzes, myrrh and frankincense, ostrich eggs, gold, silver and tin objects, a gold masked bronze goddess, several Cypriot storage pithoi, some containing jugs, bowls and lamps, Aegean pots, mainly stirrup jars, ritual vessels made from faience, thousands of beads, Baltic amber, a stone ceremonial axe from the Danube, musical instruments including a tortoiseshell lyre, bronze finger cymbals and an ivory trumpet, basketry, matting, rope, food plants such as olives, grapes, almond, figs, pomegranates, coriander, capers and safflower, orpiment used for tanning or dyeing, murex opercula used as a medicinal product, bone gaming pieces and fishing gear, 149 balance weights divided into sets to correspond to the different standards prevalent in the eastern Mediterranean and Levant, cylinder seals and scarabs, including one bearing the cartouche of queen Nefertiti, and a small folding writing board (a diptych) stored in a pithoi with a pristine wax surface ready to record a transaction.

The Cape Gelidonya shipwreck

The Cape Gelidonya shipwreck dates to about 1200 BC, about a hundred years after the Uluburun. It also sank off the Turkish coast. Whereas the Uluburun cargo could be described as general cargo, that of the Gelidonya was more orientated to the transport and trading of metals.

The Cape Gelidonya cargo

A major part of the cargo consisted of copper ingots; forty of these, including ten of which are only half preserved, are the so-called 'ox-hide' shape and more than twenty were round 'bun' ingots. Twenty-seven of the ox-hide ingots bore foundry marks, most, if not all, of which indicate a Cypriot origin. With the copper ingots were found several piles of white, powdery material, identified by Turyag Laboratories of Izmir as tin oxide.

Bronze implements were abundant: chisels, knives, hoes, flat and double axes, axe-adzes, picks, hoes or plough shares, spear-heads, bracelets, awls, bowl rims and handles, and a bronze mirror, hammer, spade, and a kebab spit. Several of the tools bore marks which seem to be Cypro-Minoan. Some of these objects were intact, but many were broken and found in groups with ingot fragments, indicating that they were being transported not for their functional use but for the metal of which they were made, in other words, scrap metal.

The vessel also contained personal items belonging to the captain and crew that indicated links with Syria and Cyprus.

A full account of the Uluburun, Gelidonya and other Bronze Age shipwrecks is in the Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea series of articles.

References

Bass, G. F. 'Cape Gelidonya and Bronze Age Maritime Trade.' In Orient and Occident, Festschrift Cyprus Gordon, edited by Harry A. Hoffner, pp. 29-38. Kevelaer, 1973.

Bass, G. F. 'Evidence of Trade from Bronze Age Shipwrecks.' In Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean, edited by N.H. Gale, pp. 69-82. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 90, Jonsered, 1991.

Beckman G. M., Hittite Diplomatic Texts, Atlanta, 1999, p. 92.

Broodbank, C. (2013) The Making of the Middle Sea. Thames and Hudson, London.

Bryce, Trevor. 2005. The Kingdom of the Hittite

Daniel M- Fernandes et. al. 'The spread of steppe and Iranian-related ancestry in the islands of the western Mediterranean', Nature Ecology and Evolution (2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1102-0

Gunbatti, C. "Two Treaty Texts found at Kültepe," in J. G. Derckson, ed., Assyria and Beyond: Studies presented to Morgens Trolle Larsen, Leiden, 2004, 249-268.

Laursen, Steffen. (2009). The decline of Magan and the rise of Dilmun: Umm an-Nar ceramics from the burial mounds of Bahrain, c.2250–2000 BC. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 20. 134 - 155. 10.1111/j.1600-0471.2009.00317.x.

Liverani, M. Prestige and Interest, International Relations in the Near East, 1600-1100 B.C., Padua, 1990;

Marcus, Ezra. (2008). Amenemhet II and the Sea: Maritime Aspects of the Mit Rahina (Memphis) Inscription. Ägypten und Levante. 17. 137-190. 10.1553/AEundL17s137.

Michel, Cécile. (2011). The Private Archives from Kaniš Belonging to Anatolians. Altorientalische Forschungen. 38. 94-115. 10.1524/aofo.2011.0007.

M. van de Mieroop, The Late Bronze Age Palace Economy: A View from the East, published in SMEA 33 (1994)

Mynarova, Jana. (2023). Across Cultures, Across Languages. Interconnectivity in the Late Bronze Age Ugarit. Diacrítica. 37. 71-81. 10.21814/diacritica.4770.

Oller, G. H. "Messengers and Ambassadors in Ancient Western Asia," in J. M. Sasson, ed., Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York, 1995, 1465-1474;

Parpola, S. "International Law in the First Millennium," in R. Westbrook, ed., op. cit., 1047-1066.

Parpola, S. and K.Watanabe, Neo-Assyrian Treaties and Loyalty Oaths, Helsinki, 1988.

Rainey, Anson. 2015. The El-Amarna Correspondence (2 vol. set)

Richard S. Hess, Amarna Personal Names. ASOR Dissertation Series 9 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1993)

Sylvie Lackenbacher and Florence Malbran-Labat, Lettres en Akkadien de la “Maison d’Urtēnu”: Fouilles de 1994, RSO 23 (Leuven: Peeters, 2016)

The Uluburun Shipwreck: An Overview by Cemal Pulak, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology in 1998.

William L. Moran (ed. and trans.), The Amarna Letters (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins UP, 1992)

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron