Civilisations that Collapsed

The 3.2k-Year BP Event: Climatic Stress and the End of the Bronze Age

This article looks at the 3.2k-year BP event, a significant period of drought around 1200 BC, and its impact on the Bronze Age civilisations of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East. We'll explore the extensive physical evidence for this climatic shift and examine contemporary written accounts that highlight the severe food shortages and societal stress experienced during this time. While climate change is a complex factor, we aim to understand its role in the widespread disruptions that marked the end of an era.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-12 | Last Updated 2025-11-26 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 4,189 times

Semi arid zone - Tabernas in Almeria

Understanding the 3.2k-Year BP Event

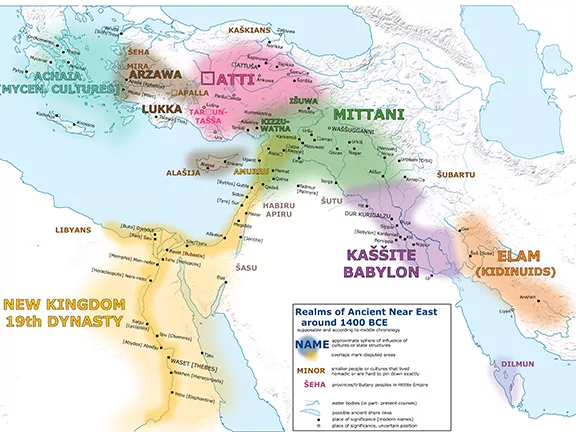

The 3.2k-year BP event refers to a rapid and prolonged drop in rainfall across parts of the eastern Mediterranean, lasting up to 300 years from approximately 1200 BC. This climatic shift led to what some researchers have termed a "megadrought" in certain regions. This event is increasingly linked to the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East and is also known by several other names, including the 3.2 ka event, the 3.2k yr BP event, and the more precise 3.2 cal ka BP event.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Scientific Evidence for the Late Bronze Age Drought

Numerous scientific studies utilising diverse proxies have provided evidence for a severe and prolonged drought at the end of the Bronze Age.

Palynology: A Window into Ancient Plant Life

Northern Syria (Kaniewski et al., 2010): Studies of core samples from alluvial deposits in northern Syria revealed a significant change in plant species between the late 13th and early 9th centuries BC. The shift to species more tolerant of dry conditions strongly indicates drier climatic conditions during this period.

Nile Delta (Bernhardt et al., 2012): A similar study in the Burullus Lagoon of the Nile delta pointed to an aridity event around 1000 BC. Researchers hypothesise this was caused by reduced rainfall over the Ethiopian plateaux, leading to lower Nile River flow, a critical lifeline for ancient Egypt.

Cyprus (Kaniewski et al., 2013): Pollen analysis from the Larnaca Salt Lake complex in Cyprus concluded that between 1200 and 850 BC, the region became significantly drier. Precipitation and groundwater levels lpotentially became insufficient to sustain agricultural practices, impacting food security.

Sea of Galilee and Dead Sea (Finkelstein and Langutt, 2013): Pollen samples from sediment cores in the Sea of Galilee and the western shores of the Dead Sea consistently show a period of severe drought beginning around 1250 BC in the southern Levant. While intense, these cores suggest the drought in this specific area began to alleviate by 1100 BC as vegetation recovered.

Israel (Kaniewski et al., 2014): Further studies of seabed core pollen off the coast of Haifa, Israel, not only confirmed drought conditions starting around 1200 BC but also indicated a change in sea level. The dramatic reduction of woodland, with forests being replaced by thorny shrub-steppe and then open steppe, underscores the severity of the desiccation. Trees did not reappear until after 850 BC.

Speleothems and Temperature Records: Clues from Caves and Oceans

Soreq Cave, Israel (Drake, 2012): Israeli scientists studying growth rings in stalagmites and stalactites (speleothems) in Soreq Cave, northern Israel, found clear evidence of low annual precipitation during the Bronze Age to Iron Age transition, consistent with drought conditions.

Mediterranean Sea Temperatures (Drake, 2012): Data assembled by Brandon Drake indicated a noticeable drop in Mediterranean sea surface temperatures between 1250 and 1197 BC. Cooler sea temperatures typically lead to reduced precipitation by decreasing the temperature differential between land and sea, impacting regional rainfall patterns.

Northern Hemisphere Temperatures (Drake, 2012): Drake also highlighted a sharp increase in Northern Hemisphere temperatures in 1225 BC, just before the collapse of the Mycenaean palaces. This warmer period may have initially caused droughts, followed by a cooler regime as these centers were abandoned. This coincided with the drop in Mediterranean Sea temperatures before 1190 BC, collectively leading to cooler, more arid conditions.

Greece (Finne et al., 2017 & 2018): High-resolution oxygen and carbon isotope data from a Greek stalagmite indicated a brief period of drier conditions around 1200 BC, with gradually developing aridity after 1150 BC. Further data in 2018 confirmed a drying trend starting around 1200 BC that lasted two centuries. The stalagmite ceased growing entirely around 1000 BC, signifying extremely dry conditions.

River Dynamics and Biological Adaptations

Nile River (Macklin et al., 2015): A comprehensive study of the Nile valley's river dynamics over millennia concluded a pronounced drought between approximately 1100 BC and 900 BC, further stressing the agricultural heartland of Egypt.

Anatolia (Roberts et al., 2016-2019): Records from various lakes in Anatolia, utilising stable isotopes and carbonate geochemistry, confirmed an arid period in the region starting around 1200 BC and persisting for decades, if not centuries.

Cattle and Grain DNA (Finkelstein et al.): Researchers studying the DNA of cattle and grain from the Bronze Age Levant found that Egyptians, anticipating harsher conditions, proactively increased grain production and bred hardier cattle. They crossed domestic humped cattle (Bos indicus or zebu) with ordinary domesticated cattle (Bos taurus) to produce more drought-resilient species. This fascinating evidence points to a conscious human adaptation to changing environmental conditions.

Dendrochronology: Tree Rings Tell a Precise Story

Juniper Wood from Türkiye (Nature, 2023): More detailed climatic information can be gleaned from ancient tree rings (dendrochronology). A study published in Nature in February 2023, based on 3000-year-old juniper wood excavated from a royal tomb in Türkiye, revealed "unusually" low growth. This suggests the region experienced a prolonged and severe drought, particularly between 1198 B.C. and 1196 B.C., an indication of intense aridity over a period of just two years.

A Note of Caution: Interpreting Climate and Collapse

While the evidence for the 3.2k-year BP event is robust, drawing definitive causal links between climate change and societal collapse requires careful consideration.

The Complex Relationship Between Climate and Civilisation

The Earth's climate has always been dynamic, and humans have adapted to countless climatic changes over hundreds of thousands of years. Throughout history, there have been other instances where climate shifts appear to coincide with major societal transformations.

Roman Empire: Kyle Harper argues that the Roman Climate Optimum (200 BC–150 AD) coincided with Rome's peak prosperity, while the Late Antique Little Ice Age (450–700 AD) acted as a catalyst for its collapse.

Other Ancient Civilisations: Some researchers propose climate change as a primary factor in the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation, the Akkadian Empire, the Old Kingdom of Egypt, and the Maya civilisations.

Shortcomings in Climate-Human Interaction Research

Recent evaluations of research on human-climate interactions, particularly by Jacobsen and colleagues, highlight several critical shortcomings:

Overreliance on Correlation: Many studies rely heavily on correlations between climate data and historical events without establishing clear causal links.

Focus on Crisis: There's a tendency to focus exclusively on periods of crisis and collapse, overlooking long-term patterns of societal adaptation and resilience.

Lack of Regional Comparisons: Detailed comparisons across diverse regions are often missing, limiting the ability to draw broader conclusions.

Proxy Limitations: Climate reconstructions derived from indirect evidence like pollen or cave formations often lack precision. They represent long-term averages rather than specific, short-term climate conditions and are inherently statistical interpretations. This makes direct links to discrete historical events challenging and complicates comparisons across different time periods.

Simplistic Assumptions: The assumption that warmer temperatures always equate to increased water availability and higher agricultural yields is overly simplistic and doesn't account for regional variations or the impact of extreme weather events.

Adapting to Change: Beyond Crisis Narratives

A review in the Nature publication observed that "populations survived—and often thrived—in the face of climatic pressures." This suggests that societies often adapted to changing climates, making the best use of new conditions. The review concluded that "the overwhelming focus in HCS [History of Climate and Society] on crisis and collapse misrepresents the character of historical interactions between humanity and climate change."

Consequently, when investigating the causes of historical collapses, researchers must exercise prudence in interpreting environmental data and thoroughly consider non-climatic factors before drawing definitive conclusions. Climate change can cause stress, but human responses to that stress are diverse and complex.

Written Evidence: Famine Across the Bronze Age World

Having given words of caution, written accounts from the late Bronze Age provide more evidence of widespread famine and desperate pleas for grain, illustrating the immediate human impact of the changing climate. The primary sources are the Ugarit Texts written between 1400 and 1185 BC.

Hittite Empire's Desperation:

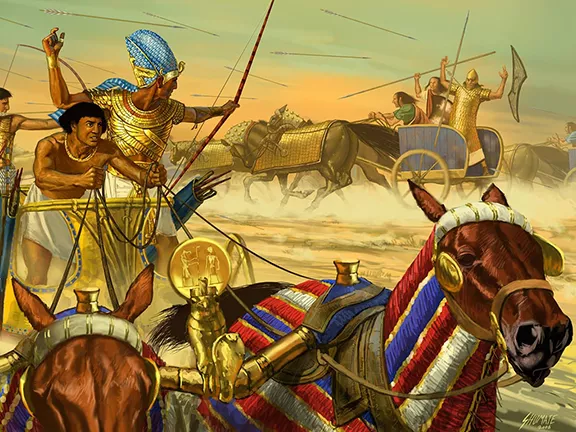

Between 1279 and 1213 BC, Hittite Queen Puduhepa wrote to Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II, stating: "I have no grains in my lands." This led to a trade embassy seeking essential barley and wheat from Egypt.

Pharaoh Merneptah (1213-1203 BC) later recorded: "caused grain to be taken in ships, to keep alive this land of Hatti," an early instance of what we would now call international famine relief.

A letter from the Hittite king to the king of Ugarit (on the Syrian coast) in the 13th century BC urgently inquired about a shipment of two thousand units of grain (up to 450 tons) from Ugarit to Hattusa, ending dramatically: "It is a matter of life or death."

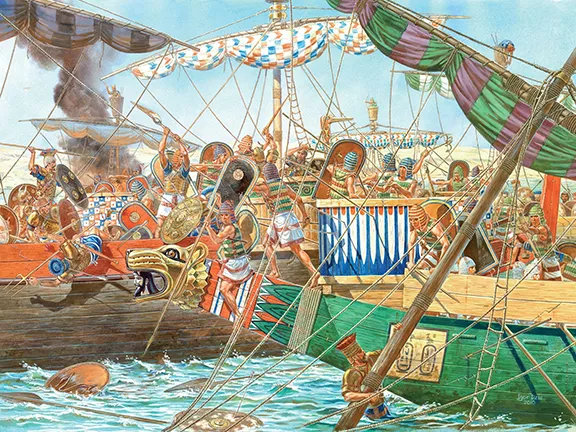

Another urgent message from the Hittite court to the Ugaritic king (either Niqmaddu III or Ammurapi) demanded a ship and crew for the transport of 2,000 kor (circa 450 tonnes) of grain from Mukish to Ura, emphasising: "You must not detain their ship!" This indicates widespread food shortages, possibly exacerbated by naval conflicts disrupting normal trade routes.

Ugarit's Struggle:

Just before its destruction in 1185 BC, a desperate letter from Emar in Syria was sent to Ugarit: "There is famine in our house, we will all die of hunger. If you do not quickly arrive here, we ourselves will die of hunger. You will not see a living soul from your land."

Even in Ugarit, famine was rampant. Pharaoh Merneptah's reply to the king of Ugarit confirms: "So you had written to me... in the land of Ugarit there is severe hunger. May my lord save the land of Ugarit and may the king give grain to save my life and to save the citizens of the land of Ugarit."

Ugaritic merchant Rapanu wrote: "The gates of the house are sealed. Since there is famine in your house, we will starve to death. If you do not hasten to come we will starve to death. A living soul of your country you will no longer see."

Towards the city's final days, an unnamed king of Ugarit lamented: "with me, plenty has become famine," and an Ugaritic official pleaded with the king: "Another thing my lord, grain staples from you are not to be had. The people of the household of your servant will die of hunger. Give grain staples to your servant."

Egyptian Challenges:

Food rationing was implemented in the final years of Ramesses III's reign (1184-1155 BC), a period that saw the world's first recorded labour strike when food rations for Egypt's favoured royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Deir el Medina could not be provisioned. This highlights the severe strain on even the most powerful Bronze Age empire.

Inter-State Cooperation and Disaster:

A remarkable letter from the king of Tyre to the king of Ugarit illustrates the cooperation between city-states, even amidst crisis. It describes a grain ship from Egypt, intended for Ugarit, caught in a storm off Tyre. The king of Tyre salvaged the grain and crew, returning them to Ugarit's care: "Your ship that you sent to Egypt died in a mighty storm close to Tyre. It was recovered and the salvage master took all the grain from the jars. But I have taken all their grain, all their people (crew), and all their belongings from the salvage master and have returned it all to them. And now your ship is being taken care of in Akko, stripped."

These numerous and varied written sources indicate that severe food shortages, likely driven by drought, were a pervasive and life-threatening reality across the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East at the close of the Bronze Age.

Lessons from the Past: Climate Change and Societal Resilience

Climate change, leading to reduced food production, undoubtedly creates stress within a society. As we observe in the 21st century, it is often the sudden, violent, and unseasonal weather events—storms, floods, unseasonal temperatures, and high winds—that cause the most distress, making it difficult for farmers to reliably grow and harvest crops. This reduces a nation's capacity to feed its own population or produce a surplus for trade.

However, the past also teaches us that while a change in climate can have a detrimental effect in one region, it can bring distinct advantages in another. The diverse responses of Bronze Age civilisations to the 3.2k-year BP event underscore the complexity of human-climate interactions. While some societies faced existential threats, others adapted, migrated, or even thrived in the face of changing conditions. The resilience and adaptability of human populations should be a central focus when examining historical climatic shifts.

How far were the drying effects of the 3.2k year BP event felt?

For completeness we shall take a brief look at the same period in the western and central Mediterranean.

The 3.2k-year BP event created a distinct "climate dipole" across the Mediterranean, characterised by a sharp contrast between the arid East and the humid/stable West. This pattern was likely driven by a shift in the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which diverted storm tracks toward the western Mediterranean and away from the Levant.

The Maghreb (Morocco): "Cold & Wet" Anomaly

The most significant evidence for the "anti-drought" (wet phase) comes from the Middle Atlas Mountains. While the East dried out, this region experienced a surge in moisture.

High-resolution sediment cores (diatoms and oxygen isotopes) reveal a distinct "pluvial" (wet) phase known as the 3.2 ka Wet Event.

Lake levels at Sidi Ali rose significantly between 1150 and 950 BC, coinciding with the collapse of Eastern Mediterranean powers. This wet phase was driven by a negative NAO-like atmospheric pattern that pushed Atlantic moisture southwards into North Africa.

The Iberian Peninsula (Spain): Stability

Varved (annually laminated) lake sediments provide a continuous, high-resolution record showing no evidence of a "megadrought" around 1200 BC.

The records indicate that the major aridity crisis in Spain occurred much earlier (c. 1550 BC, linked to the Argaric collapse). By 1200 BC, Lake Montcortès (Pyrenees) actually recorded a transition toward deeper, more stable lake conditions rather than desiccation.

Central and Southern Italy: The "Climate Border"

Italy appears to be a transition zone. The north-central areas saw humidity similar to the West, while the extreme south and islands aligned with the dry East.

Central/Northern Italy (Humid)

Evidence comes from lake level reconstructions.

Lake Accesa (Tuscany) recorded a highstand (high water level) around 1200 BC, consistent with the wet signal seen in Morocco and Spain.

Southern Italy & Sicily (Arid)

Evidence here is mainly from archaeological abandonment and speleothem data.

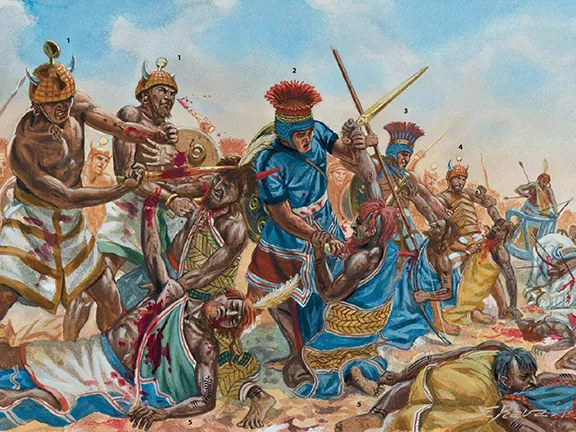

The island of Ustica (north of Sicily) was abruptly abandoned around 1250–1200 BC. New research hypothetically links this directly to a severe drought that made the island's agriculture unviable, thus aligning southern Italy with the "Eastern" drought block. Migrations West to East Some scholars attempt to show that one group of the infamous ‘Sea Peoples’ originated in Sardinia (the Sherden) or Sicily (Shekelesh or Sikels) and that they were migrating to pastures new. If that is the case, then they moved from the frying pan into the fire.

References

Bernhardt, C., et al.** (2012). "A 7000 yr palynologic record from Burullus Lagoon, Nile Delta, Egypt..."

Cline, Eric. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Corella, J. P. et al. (2016). "Climate and human impact on a meromictic lake during the last 6,000 years (Montcortès Lake, Central Pyrenees, Spain)." Journal of Paleolimnology.

Degroot et al. “Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change.” Nature, vol. 591 (25 March 2021): 539–550.

Drake, Brandon. (2012). The influence of climatic change on the Late Bronze Age Collapse and the Greek Dark Ages. Journal of Archaeological Science. 39. 1862–1870. 10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.029.

Fairchild et al. “Modification and preservation of environmental signals in speleothems.” Earth Science Reviews, vol. 75: 105–153

Finkelstein, I., & Langgut, D.** (2013). "The Climate Crisis at the End of the Late Bronze Age: A New Perspective from the Southern Levant." Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, 40(2), 143-162. (Also related to their subsequent work on cattle and grain DNA, often associated with Tel Aviv University and "Exact Life Sciences" research).

Finne, M., et al.** (2017). "Late Holocene climate dynamics in the northern Mediterranean based on stable isotope records from a stalagmite from Greece." *Quaternary Science Reviews*, 174, 91-105.

Harper, Kyle. The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Incarbona, A. & Foresta Martin, F. (2025). "Late Bronze Age Collapse at Ustica Island (Sicily – Italy): The Drought Hypothesis." Alpine and Mediterranean Quaternary.

Izdebski et al. “The environmental, archaeological and historical evidence for regional climatic changes and their societal impacts in the Eastern Mediterranean in Late Antiquity.” Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 136 (2016): 189–208

Jacobsen, Matthew, Jordan Pickett, Alison Gascoigne, Dominik Fleitmann, and Hugh Elton. “Settlement, environment, and climate change in SW Anatolia: Dynamics of regional variation and the end of Antiquity.” PLoS One, June 27 2022

Kaniewski et al. “Late second-early first millennium BC abrupt climate changes in coastal Syria and their possible significance for the history of the Eastern Mediterranean.” Quaternary Research, vol. 74 (2010): 207–215

Kaniewski, D., et al.** (2010). "The 1200 BC drought in the Eastern Mediterranean: New archaeological and palynological evidence from northern Syria." *Quaternary Science Reviews*, 29(1-2), 17-27.

Kaniewski, D., et al.** (2013). "The 3.2 ka BP event: A major drought in the Eastern Mediterranean around the end of the Late Bronze Age." *PLoS ONE*, 8(8), e72911. (Focuses on Larnaca Salt Lake).

Kaniewski, D., et al.** (2014). "A high-resolution palynological record of climatic and anthropogenic change from the coastal environment of Haifa, Israel." *Journal of Archaeological Science*, 49, 442-452.

Langutt, Dafna, Israel Finkelstein, and Thomas Litt. “Climate and the Late Bronze Collapse.” Tel Aviv, vol. 40 (2013): 149–175

Macklin, M. G., et al.(2015). "Holocene environmental change in the Nile valley and delta: Implications for early human settlement and agricultural development in Egypt." *Quaternary Science Reviews*, 129, 303-324.

Magny, M. et al. (2007). "Holocene climate changes in the central Mediterranean as recorded by lake-level fluctuations at Lake Accesa (Tuscany, Italy)." Quaternary Science Reviews.

Manning, S. W., et al. (2023). "Extreme drought at the end of the Late Bronze Age in the Near East." *Nature*, 614, 280-287.

Zielhofer, C. et al. (2017). "Atlantic forcing of Western Mediterranean winter rain minima during the last 12,000 years." Quaternary Science Reviews.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron