Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

The Early Bronze Age shipwreck at Dokos (2200 BC)

As of October 2023, archaeologists consider the Dokos shipwreck the oldest known underwater shipwreck discovery. They dated the wreck to the second Early-Helladic period, between 2700 and 2200 BC.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-13 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 10,933 times

Early Helladic flask - Photos: Kyle Jachney, Nikos Tsouchlos, Kostas Xenikakis

Where was the Dokos shipwreck found?

The remains of the shipwreck are located about 15 to 30 metres underwater off the coast of southern Greece in Skindos Bay on the island of Dokos in the Aegean Sea. Dokos is about 100 kilometres east of Sparta, in the Peloponnese region.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

About the Dokos wreck site

Dokos wreck - Photos: Kyle Jachney, Nikos Tsouchlos, Kostas Xenikakis

The island of Dokos is located in the Argo-Saronic Gulf between Spetses, Hydra and the mainland town of Hermione. Dokos was called Aperopia in ancient times. It has a strategic position on the sea routes to and from the Argolic Gulf and the eastern shores of Laconia. It was thinly inhabited during the Neolithic era (4th millennium BC), but the human presence increased during the Early-Helladic era (3rd millennium BC) when navigation and maritime transit trade developed. Dokos disappeared from the record for a time, becoming the habitation of fishermen and shepherds.

During the 13th c. BC, the settlements of Myti Kommeni and Ledeza were established on the island. Dokos has few natural springs and is a barren island with a total height of 308 metres above sea level.

Who excavated the Dokos shipwreck?

The underwater archaeological research on the island of Dokos was carried out by the Institute of Marine Archaeological Research, under the direction of archaeologist Giorgos Papathanasopoulos. It was recorded as the first systematic investigation of an ancient shipwreck in Greece, using the most modern technological methods for the time.

On August 23, 1975, Peter Throckmorton, pioneer seabed researcher and founding member of I.EN.A.E., located an extensive concentration of prehistoric pottery fragments at the bottom of Scinto Bay, Dokos Island, at a depth of 20 meters.

An autopsy and two preliminary reconnaissance investigations followed in 1975 and 1977, under the scientific direction of the archaeologist and then president of I.EN.A.E. Giorgos Papathanasopoulos and the technical organization of Nikos Tsouchlos. The start of the systematic excavation of the wreck of Dokos began in 1989 and evolved into four excavation periods (1989-1992).

It was established that the ceramic findings, scattered on the seabed at a depth of 15m. up to 32 m., were part of the cargo of a ship of the Early Helladic II period. It was therefore the oldest known shipwreck in the world until then.

When did the Dokos wreck sink?

The style of Cycladic pottery found on the wreck is called Early Helladic II pottery. This Helladic pottery technology developed before the invention of the pottery wheel has been fairly conclusively dated to about 2200 BC. Helladic II pottery was manufactured on mainland Greece during the early Bronze Age between about 2650 and 2200 BC. This period is increasingly being called the Korakou culture.

How was the Dokos ship built and what were its dimensions?

The ship itself is long gone, as everything biodegradable has been dissolved by the sea.

The anchors found near the wreck weighed 18.5kg and 21.5kg. If these anchors did belong to the wreck, they suggest an overall length of 15 - 20 metres, quite a substantial size for the period.

Who were the people who owned and operated the ship?

This is an interesting question. 2200 BC is very early for the ship to be Minoan although this must be a possibility. It is more likely that the Dokos ship was a local trading vessel engaged on short coastal journeys between settlements.

Where did the crew of the Dokos shipwreck originate?

Again, this is an interesting question. Most likely the crew were fairly local to the area in which the ship sank, perhaps from the Attica or Argolid regions. In the early period of maritime trade, local knowledge of the coast, tides and currents was essential.

What was the cargo on the Dokos ship?

Early Helladic bottle - Photos: Kyle Jachney, Nikos Tsouchlos, Kostas Xenikakis

The cargo carried by the Dokos is impressive for its volume and the variety of ceramic types it includes. Deep spouted sauceboats in a variety of shapes and sizes, cutaway jugs, shallow and deep bowls, amphorae, plates, cups, jars, askoi, pithoi, household utensils and grinders. It undoubtedly represents one of the largest known to date sets of Early-Helladic II ceramics and testifies to the high level of ceramic technology of the time, just before the introduction of the pottery wheel. The vessel also carried grinding wheels, fragments from the same lead ingot and obsidian blade shafts.

Fragments of a pyxis, a cylindrical or spherical box or vase with a lid were also found.

Although not part of a cargo, during the excavation, about 40 metres from the main concentration of the ceramic load, two stone slab anchors belonging to a known Bronze Age anchor type were found.

The two anchors are about the same weight and were made from hard grey-green schist. They have a hole near the circumference. In several parts of the circumference, they have dents, a result of wear and tear from their use. They were found wedged into the rocky bottom with the hole facing the surface of the sea and towards the east, i.e., towards the area of the main concentration of the cargo and the mouth of the cove. Their location indicates they were from the Dokos wreck.

Where did the Dokos cargo come from?

Most of the vases that compose the cargo must be the product of a thriving workshop in some large residential centre. After further inspection of the sauceboats, it has been suggested that these types resemble those from Askitario in Attica, and are also comparable to ones from Lerna in the Argolid, Lithares in Boetia and from the Cyclades.

The obsidian probably originated on the island of Milos some 120 kilometres southeast of Dokos or Antiparos 160 kilometres due east of Dokos.

It is known that lead was being mined at Lavrion during this period and this may have been the origin of the lead ingot. Lavrion lies on the east coast of the Attica region about 70 kilometres northeast of Dokos and 30 kilometres south of Askitario.

Where was the cargo going?

The cargo could have been intended for distribution to smaller coastal settlements in the Argolic Gulf. However, the island of Hydra is an interesting speculation. Hydra had a thin population of farmers and herders who had been there since about 2500 BC. With no pottery industry themselves, they may well have been customers for the Dokos ship. Obsidian from Milos has also been found on Hydra.

The island of Dokos itself is also an interesting speculation. Dokos was sparsely inhabited from the end of the Neolithic period, but human presence on the island increased during the Early Helladic period (2500 - 2200 BC), as coastal sea trading was developing.

Where did the Dokos ship come from and where was it going?

If the ship had picked up lead and pottery from the east coast of the Attica region, then it had sailed across the mouth of the Saronic Gulf. Dokos is midway between the ancient settlement of Hermione on the mainland and the island of Hydra. Dokos island would be a natural place to take shelter from a storm for ships sailing out of the Saronic Gulf bound for the Argaric Gulf.

Why did the Dokos ship sink?

It is not known why the Dokos ship sank. If the stone anchors found near the wreck were part of the ship's gear, then it might indicate that they were dropped to secure the ship's head to wind in Skindos Bay, perhaps in a storm. Efforts to save the ship failed and it was overwhelmed and sank.

Political situation at the time

The people of the Korakou culture (2650 to 2200 BC) lived in the Peloponnese, Attica, the island of Euboea (Evia) plus Locris, Boeotia, and Phocis in central Greece. Many coastal sites were fortified, and in several areas the period ends with a destruction by burning. Some settlements were re-occupied by the Tiryns culture that followed the Korakou, while many remained unoccupied until the Mycenaean period.

It was during this period that bronze working was introduced to the area and oxen were first used to draw a plough. The culture had a hierarchical social organization, and monumental architecture and fortifications but no indication of long-distance maritime trading in their own right.

Examples of Early-Helladic II pottery have been found as far away as Knossos in Crete, Lefkas in the west, Thessaly, and on Ios and Keos in the Cyclades.

There was clearly a thriving maritime trade at this time using local boats sailing within sight of the coast or offshore islands, pre-dating the more long-distance trade initiated by the Minoans.

Ongoing Research

The cargo from the wreck of the Dokos continues to be studied and placed into conservation at the Spetses museum.

Where is the Dokos shipwreck now?

The cargo from the wreck of the Dokos ship can be seen at the Spetses museum.

References

Institute of Marine Archaeological Research

Papathanasopoulus G. ENALIA vol1, 1990, 10 - 40

Enalia Annual 1990, Vol 2 (publ. 1992). HIMA, Athens

Master Seafarers: The Phoenicians and the Greeks (Periplus, 2004), 98-105

Agouridis, C., Y. Vichos, 1997: 'Scientific activities of the Greek Institute of Marine Archeology (HIMA)', DEGUWA , Newsletter 13, 7th year, 27-31.

Agouridis, C. 1997: 'Sea routes and navigation in the Third Millennium Aegean', Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 16.1, 1-24.

Agouridis, C. 2000: 'Seafaring, Trade and Cultural Contact in the Aegean during the Early Bronze Age', IKUWA, protection of underwater cultural heritage, changes in European lifestyle through river and sea trade, contributions to the International Congress of Underwater Archeology (IKUWA '99 ), 18.-21. February 1999 in Sassnitz on Rogen , Libstorf 2000, 101-112.

Vichos, G. 1993: "The shipwreck of Dokos: The archaeological investigations and findings of the Protohelladikos shipwreck", The Kathimerini: Seven Days , Sunday 13 June 1993, 16 -18.

Vichos, G. 1998: "Treasures from the depths of time: The important finds of the prehistoric wrecks of Dokos and Iria", Kathimerini: Seven Days , Sunday 26 July 1998, 10.

Dickinson, O. 1994: The Aegean Bronze Age, Cambridge University Press, 238,240.

Karageorghis, V. 1999: 'Notes on some enigmatic objects from the Prehistoric Aegean and other East Mediterranean regions', AA 1999, 501-514.

Koutsouflakis, G. 1990 'Trade mechanisms in the Early Bronze Age', Hydra 7, 27-39.

Kritzas, X. 1989: "History of Dokou research: Continuation of the reconnaissance research (1977)", Enalia , Vol. I, Vol. II, 10-11.

Kyrou, A.K. 1990: At the crossroads of Argoliko , Vol. 1 , Athens.

Lolos, Y.G. 1995: 'Late Cypro-Mycenaean Seafaring: New Evidence From Sites in the Saronic and the Argolic Gulfs', Proceedings of the International Symposium 'Cyprus and the Sea', Nicosia, 25-26 September 1993, Nicosia, 66-69.

Lolos, YG 1999: 'On recent Early Mycenaean finds from the Aegean island of Dokos', C. Giardino, Maritime Cultures in the Central and Western Mediterranean between the 17th and 15th Centuries BC , Bagatto Libri, Rome , 67-73.

Lolos, Y.G. and Chr. Marabea 2004: 'Mycenaean Aperopia: Thoughts about working areas and production systems', VIII, 65-73 (Appendices I&II, 74-78).

Marabea, Chr. 2002: Late Helladic III working areas in settlements and sanctuaries on the Greek Mainland, M.A. Thesis, University College, London, 47-50, 56.

Papathanasopoulos, G. 1976: "The Proto-Helladic shipwreck of the island of Dokos", AAA IX, 17-23.

Papathanasopoulos G., Vichos G. and G. Lolos 1994: "Dokos: The oldest known shipwreck in the world", about Experiment , Year 1, No. 3 (Summer 1994), 76-113.

Papatheodorou G., Geraga M., Kastanos N., Gionis G., Hasiotis T., Halari A. and G. Ferentinos 2002: The study of the coastal paleogeography of the island of Dokos with the application of marine geophysical methods, University of Patras (18 pages). Study, under publication, submitted to I.EN.A.E.

Parker, A.J. 1990: 'Classical Antiquity: The Maritime Dimension', Antiquity Vol. 64, No. 243, 335.

Throckmorton, P. 1977: Diving for Treasure, Thames and Hudson, London, 60-61.

Throckmorton, P. 1987: History from the sea: Shipwrecks and Archaeology, Mitchell Beazley, London,34-36.

Vichos, Y. G. Papathanassopoulos 1996 : 'The excavation of an Early Bronze Age cargo at Dokos: The first two campaign seasons (1989-1990)', ??? H. Tzalas, Tropis IV: 4th International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Athens, 1991 (Proceeding), Athens, 519-538.

Vichos Y., Tsouchlos N., G. Papathanassopoulos 1991: 'First year of excavation of the Docos wreck, Thalassa': The prehistoric Aegean and the sea, R. Laffineur, L. Basch, Proceedings of the third International Aegean Meeting of the University of Liege, Underwater and Oceanographic Research Station (StaReSO), Calvi, Corsica (April 23-25, 1990), Aegaeum 7, 147-152, Pls . XLI-XLIV.

https://ienae.gr

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dokos_shipwreck

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

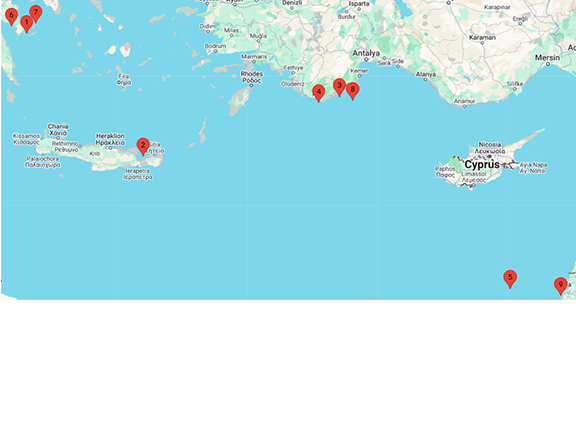

2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC

2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC 3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC

3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC 4: Uluburun Shipwreck 1335 - 1305 BC

4: Uluburun Shipwreck 1335 - 1305 BC 5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck

5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck 6: Point Iria Shipwreck c 1200 BC

6: Point Iria Shipwreck c 1200 BC 7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC

7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC 8: Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC

8: Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC 9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast

9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast 10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques

10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques 11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary

11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary