Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

The Cape Gelidonya shipwreck c 1200 BC

The Cape Gelidonya late bronze age shipwreck that sank about 1200 BC is one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

By Nick Nutter on 2023-10-31 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 5,325 times

Dive boat over the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck

Where was the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck found?

The Cape Gelidonya wreck is located off the coast of southern Turkey, near the town of Fethiye. It lies in about 28 meters of water, just south of Devecitasi Adasi, one of the Be Adalar (Five Islands).

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

About the Cape Gelidonya wreck site

Location of Cape Gelidonya shipwreck

Cape Gelidonya is known today, and was known in antiquity, as a dangerous point for coastal shipping. Steep cliffs plunge into the sea, there are few bays to offer shelter and the seabed inshore, although sandy, has pinnacles of rock rising to or just under the surface.

Who found the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck?

The Cape Gelidonya shipwreck was found by Kemal Aras, a sponge diver from Bodrum, Turkey, in 1954.

Aras was diving for sponges when he spotted a large pile of metal ingots on the seabed. He realized that he had discovered an ancient shipwreck, and he reported his find to American journalist and amateur archaeologist Peter Throckmorton.

Throckmorton was cataloguing ancient wrecks along the southwest Turkish coast at the time. He was able to locate the site in 1959 and, recognizing its great age, asked the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania if it would organize its excavation.

Who excavated the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck?

In 1960, a team of archaeologists and divers, led by Throckmorton and George Bass (the father of underwater archaeology), began excavating the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. The team also included Joan du Plat Taylor and Frederic Dumas.

In addition to the 1960 excavation, there have been several other surveys and excavations at the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck site. In the 1980s and 1990s, teams of archaeologists conducted surveys of the site, and in 2010, a team from the Institute of Nautical Archaeology conducted another excavation.

When did the Cape Gelidonya wreck sink?

The Cape Gelidonya ship sank in the Late Bronze Age, between 1200 and 1150 BC.

How was the Cape Gelidonya ship built and what were its dimensions?

The Cape Gelidonya ship was built using a carvel construction technique. This technique involves building the ship's hull by joining planks together edge-to-edge, rather than overlapping them. The planks are then fastened together with mortise and tenon joints and pegs. The planks recovered were 10 - 15mm. thick and from 5 to 15 cm. wide; none was preserved to any great length. Neatly cut dowel holes, 1.5 to 2 cm. in diameter, were found in several planks, and the actual dowels were in place in a few instances.

Furthermore, its brushwood dunnage gave for the first time meaning to the 'wattle fencing' Odysseus placed in a vessel he had built in the Odyssey. Dunnage is material such as straw or in this case brushwood placed around a cargo to prevent damage. It should be noted how well our ship fits the description of the small boat (not, it would seem, a raft) built by Odysseus with the aid of Calypso.

The ship's hull was made of pine wood, and the deck was made of cypress wood.

The ship was also equipped with a mast and a sail.

The Cape Gelidonya ship was approximately 15 meters long and 4 meters wide. It had a capacity of about 10 tons.

Who were the people who owned and operated the ship?

The ship was probably Canaanite, or early Phoenician although there was the possibility that the ship was Cypriot, because so many Near Eastern artifacts have been found on Cyprus from the same period.

Where did the crew of the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck originate?

The origin of the crew of the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck is unknown. However, based on the ship's cargo and its construction, it is likely that the crew was from the eastern Mediterranean region, possibly Syria or Cyprus. However, it is also possible that the crew of the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck was from a different region of the Mediterranean, such as Greece or Crete. The ship's cargo was destined for a variety of markets, and it is possible that the crew was made up of merchants and sailors from different regions.

What was the cargo on the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck?

Myceanean stirrup jar - Cape Gelidonya wreck

The major part of the cargo consisted of copper ingots; forty of these, including ten of which are only half preserved, are the so-called 'ox-hide' shape (average length 60 cm average width 45 cm., average weight 20.5 kg, but varying between 16 and 27 kgs.), and more than twenty were round 'bun' ingots (average diameter 20 cm., average thickness 2.5 cm., average weight 4 kg.). Twenty-seven of the ox-hide ingots bore foundry marks, most, if not all, of which indicate a Cypriot origin.

The whole ingots were stacked in piles, but ingot fragments were found in small groups that were probably held together in bags or baskets; bits of matting were found running over some ingots, and part of a basket, which contained several tools, was well-preserved.

With the copper ingots was found several piles of white, powdery material, identified by Turyag Laboratories of Izmir as tin oxide. Thus, the merchant ship was carrying the raw materials for making bronze: copper, almost certainly from Cyprus, and tin perhaps from Turkey or even Afghanistan (a la the Uluburun wreck).

Bronze implements were abundant: chisels, knives, hoes, flat and double - axes, axe-adzes, picks, hoes or plough shares, spear- heads, bracelets, awls, bowl rims and handles, and a bronze mirror, hammer, spade, and a kebab spit; several of the tools bore marks which seem to be Cypro-Minoan. Some of these objects were intact, but many were broken and found in groups with ingot fragments, indicating that they were being transported not for their functional use but for the metal of which they were made.

A number of whetstones were found with some of the tools.

Weapons included spearheads, one with rounded midrib and flat, triangular tang with two rivet holes, and two tiny halberds or billhooks, with pointed ends and rectangular blades.

A cabin or some living quarters seems to have been in the eastern end of the wreck sometimes called the "captain's quarters" because of the quantity of personal possessions. Here were found traces of the crew's food (olive pits, an astragal, fish bones, and a possible bird bone) near what may have been firewood.

This was also the area that contained almost all of the personal objects: two polished stone mace-heads, one with a metal lining in its perforation and the other with a collar carved around the perforation on one side. It is interesting to note that similar perforated stone hammers were sometimes used for metal working in the Bronze Age. There were also pieces of crystal, and a pottery lamp.

Amongst these personal items were three complete scarabs, one fragment of a scarab, and a scarab-shaped plaque which was inscribed on both faces. The latter had a length of 8 cms and depicted the god Re with falcon's head and a human's body, the left arm of which terminates in an uraeus-serpent and can be dated with almost complete certainty to the Ramessid Egyptian Dynasty (1292 to 1189 BC); the greater number of those scarabs with parallel motifs and iconography seem to come from Levantine sites.

A merchant must have weights, and 48 of these were found in the 'captain's quarters', forming three sets. Those of the ovoidal, or sphenoidal, class are approximate multiples of nine and a fraction gram and the smallest of these, marked with a unit sign on its top, is exactly 9.3 grams, an Egyptian qedet. This is a standard also used in Cyprus and Syria. Other weights were cylindrical and domed, but their standards have not yet been determined. Most were made of hematite.

Probably from the same area, was a finely carved cylinder seal, showing two worshippers facing a deity wearing the atef crown. It seems to have been made in North Syria sometime during the 18th or 17h century BC. That it was still in use some centuries later is not unusual.

At the western end of the wreck a jar of glass beads of three types was found.

Pottery was scattered throughout the wreck; some sherds having drifted quite some distance away. The pottery is still under study, but some seems certainly Cypriot. Several distinctive pieces, however, including two Mycenaean type IIIB stirrup jars, a base-ring jug, and large storage jars, are best placed in the 13th century, BC some of these tend to be of a design used late in that century. In addition to its cargo, the ship was carrying approximately 116 kgs. Of ballast stones.

Where did the Cape Gelidonya cargo come from?

Scarabs - Cape Gelidonya wreck

The Cape Gelidonya ship's cargo came from all parts of the eastern Mediterranean. The pottery finds parallels from the Greek mainland to the Levantine coast as well as Cyprus. The scarabs originated in Egypt, whilst the cylinder seal came from Syria. The weights are from Cyprus and Syria. The copper and bronze were almost certainly from Cyprus. Many of the marks on the ingots are identical to potters' marks from Cyprus and from the Cypriot colony near Ras Shamra in Syria.

The shapes of the tools seem also to be Cypriot, although some of their closest parallels come from the Acropolis hoard in Athens.

The tin could be from a few places including Turkey and Afghanistan.

What was the purpose of the cargo?

Double bladed bronze axe - Cape Gelidonya wreck

The copper and tin were undoubtedly going to be used to manufacture bronze. Many of the bronze items on board also appear to be scrap items that would have been melted down.

The cargo suggests that the ship was involved in the long-distance trade of metals. The metal-working tools suggest that the ship may have carried a metalsmith on board.

Where was the Cape Gelidonya cargo going?

Copper ingots - Cape Gelidonya wreck

The cargo would probably have been bound for one of the Mycenaean ports.

Where did the Cape Gelidonya ship come from and where was it going?

The Cape Gelidonya shipwreck likely came from the Levant, a region that includes modern-day Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine, via Cyprus and possibly Mycenae based on the following evidence:

The ship was carrying a cargo of copper and tin ingots, scrap bronze tools, weapons, and other objects, as well as metal-working tools. Analysis of the copper ingots showed it came from Cyprus, and the tin likely came from Turkey or Afghanistan via a Levantine port.

The ship also had several personal belongings that were likely of Levantine origin, such as a lamp and a pair of stone mortars.

A later find included two Mycenaean stirrup jars that would have been manufactured at Mycenae in modern day Greece.

Why did the Cape Gelidonya ship sink?

The reasons why the Cape Gelidonya ship was wrecked are unknown. It is interesting that it founded in the same general location as the Uluburun wreck a hundred years earlier. One possibility is that the ship sank due to a storm. The Cape Gelidonya ship apparently ripped its bottom open on a pinnacle of rock that nears the surface of the sea just off the northeast side of Devecitasi Adasi, the largest of the islands just off the coast. Spilling artifacts in a line as she sank, the ship eventually settled with her stern resting on a large boulder 50 meters or so away to the north.

Political situation at the time

1200 BC is, traditionally, the date given for the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Kassites in Babylonia, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and the Levant, and the New Kingdom of Egypt, as well as the destruction of Ugarit and the Amorite states in the Levant, the fragmentation of the Luwian states of western Anatolia, and a period of chaos in Canaan.

Along with a cultural collapse, the whole region was affected by attacks from the so called 'Sea People' between 1200 and 1150 BC and some of the cities in the Middle East were destroyed during this period, although nowhere near as many as was first thought. The 'Sea People' made sporadic raids until about 800 BC. This is the period of the fall of Troy (1180 BC) and the collapse of the Mycenaean palaces.

A few powerful states survived the collapse or were able to recover quickly including the Assyrians, the New Kingdom of Egypt, the Phoenician city states, and Elam. Elam was an ancient civilization centred in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran.

In addition to the invasions of the Sea Peoples, various explanations for the collapse have been proposed, including climatic changes causing a period of prolonged droughts or the effects of volcanic eruptions, a lack of copper and tin such that the elites were not able to maintain their lifestyles, effects of the spread of iron metallurgy, developments in military weapons and tactics, and a variety of failures of political, social and economic systems, but none has achieved consensus. More than one of these factors probably played a part.

There is no doubt that the uncertainty of the times was reflected in the amount and value of goods being transported around the eastern mediterranean and by whom those goods were carried.

Ongoing Research

There are many ongoing research projects on the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. One of the most significant projects is the final publication of the wreck in its entirety. This project is being led by Dr Joseph W. Lehner, Assistant Director of the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology.

The project is expected to take several years to complete, and it will involve a wide range of experts, including archaeologists, scientists, and conservators. The goal of the project is to produce a comprehensive and definitive publication of the wreck and its cargo.

Another ongoing research project on the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck is focused on the use of lead isotope analysis to determine the source of the metal ingots found on the ship. Lead isotope analysis is a technique that can be used to identify the source of metal objects based on the unique isotopic signature of the lead in the metal.

This research project is being led by Dr Ozlem Dogan, a researcher at the University of Tubingen in Germany. The goal of the project is to better understand the trade networks of the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean by determining the source of the metal ingots on the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck.

In addition to these two major research projects, there are other ongoing research projects on the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. These projects are focused on a variety of topics, including the ship's construction, its cargo, and its crew.

Where is the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck now?

The Cape Gelidonya wreck and its cargo cannot be seen in person. The wreck is in 28 meters of water off the coast of southern Turkey, and it is protected by Turkish law. It is not possible to visit the wreck site without a permit.

However, there are a couple of museums in Turkey that have exhibits on the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, including the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology and the Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

These museums have a variety of artifacts from the shipwreck on display, including copper and tin ingots, scrap bronze tools, weapons, and other objects. The museums also have exhibits that explain the history of the shipwreck and its significance to our understanding of the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean.

References

Bass, G. F. Cape Gelidonya: A Bronze Age Shipwreck. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 57 (part 8). Philadelphia, 1967.

Bass, G. F. 'Cape Gelidonya and Bronze Age Maritime Trade.' In Orient and Occident, Festschrift Cyprus Gordon, edited by Harry A. Hoffner, pp. 29-38. Kevelaer, 1973.

Bass, G. F. Archaeology Beneath the Sea, pp. l-59. New York, 1975.

Bass, G. F. 'Evidence of Trade from Bronze Age Shipwrecks.' In Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean, edited by N.H. Gale, pp. 69-82. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 90, Jonsered, 1991.

Bass, G. F. 'Return to Cape Gelidonya.' INA Newsletter 15.2 (June 1988): 2-5.

Hirschfeld, N. 'Cape Gelidonya Shipwreck: A Closer Look at the Ceramics.' INA Quarterly 45.3/4:22-27.

Throckmorton, Peter. 'Oldest Known Shipwreck Yields Bronze Age Cargo.'

National Geographic 121.5 (May 1962): 696-71 l.

Throckmorton, Peter. The Lost Ships: An Adventure in Underwater Archaeology. Boston and Toronto, 1964.

Late Bronze Age Collapse: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Bronze_Age_collapse

https://nauticalarch.org/projects/cape-gelidonya-late-bronze-age-shipwreck-excavation/#:~:text=That%20archaeologist%20was%20George%20Bass,of%20both%20copper%20and%20tin.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

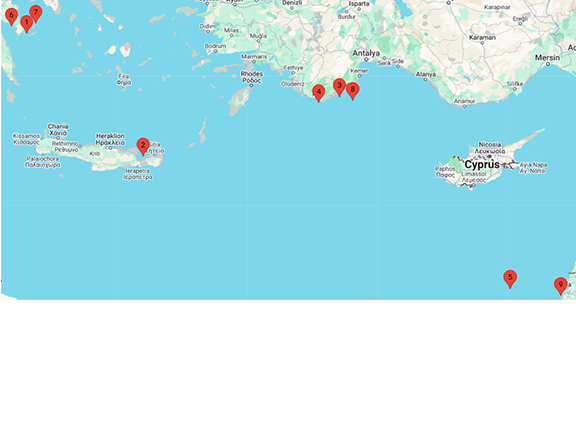

1: Dokos Shipwreck 2200 BC

1: Dokos Shipwreck 2200 BC 2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC

2: Pseira shipwreck 1725 to 1675 BC 3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC

3: Kumluca shipwreck 1600 - 1500 BC 4: Uluburun Shipwreck 1335 - 1305 BC

4: Uluburun Shipwreck 1335 - 1305 BC 5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck

5: Deep Water Late Bronze Age Wreck 6: Point Iria Shipwreck c 1200 BC

6: Point Iria Shipwreck c 1200 BC 7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC

7: Modi Island Shipwreck c1200 BC 9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast

9: Late Bronze Age wrecks on the Carmel coast 10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques

10: Bronze Age boatbuilding techniques 11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary

11: Bronze Age Wrecks - Summary