Civilisations that Collapsed

Were the Habiru responsible for the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations in the Middle East?

Mercenaries in the Middle East are nothing new. The Habiru were renowned for their ferocity and for fighting for the highest bidder. They made no small contribution to the instability of the Bronze Age world in the Middle East.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-17 | Last Updated 2025-11-28 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 5,901 times

The Habiru - A bronze age mercenary band of brothers Image: Painting by Igor Dzis/Karwansary Publish

Who Were the Habiru?

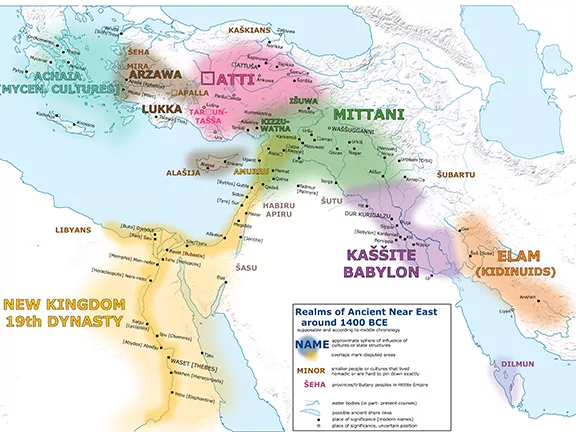

In the diplomatic archives of the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1200 BCE), a specific group of people appears repeatedly. They are described with fear by local governors, with annoyance by Pharaohs, and with opportunism by rebel leaders. They were the Habiru (also spelled Hapiru, Hapiri or Apiru).

For decades, historians attempted to pin them down as a specific tribe or nation. Today, however, the consensus is far more fascinating: the Habiru were not a race, but a social class, a vast, multi-ethnic underclass of outlaws, refugees, and mercenaries who rejected the rigid palace systems of the great empires.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Habiru in Ancient Middle East Texts?

The Habiru are the first mercenaries of which we have direct evidence. Habiru is a term used in 2nd-millennium BC texts throughout the Middle East for a social status of people who were variously described as rebels, outlaws, raiders, mercenaries, bowmen, servants, slaves, and labourers, who led a nomadic, marginal and sometimes lawless existence on the fringes of settled society in the Levantine region.

Did the Habiru Have a Common Ethnic Origin or Language?

The Habiru had no common ethnic affiliations and no common language, their personal names being most frequently West Semitic, but also East Semitic, Hurrian, or Indo-European.

Texts and inscriptions that mention the Habiru

The Habiru are first mentioned in cuneiform tablets and inscriptions dating back to about 1760 BC. By the 14th century BC, their numbers had grown to such an extent that they were a force to be reckoned with.

The Mari Archives (18th century BC)

Between 2900 and 1759 BC, Mari was a wealthy hegemonic city-state in modern day Syria on the western banks of the Euphrates river.

The texts from Mari (c. 1760 BC) are exceptionally valuable because they predate the Amarna and Nuzi texts by nearly 400 years. They were written towards the end of Mari’s existence. Babylon invaded the city-state in 1761 BC and subsequently destroyed it in 1759 BC.

While the later Amarna letters show the Habiru as a massive geopolitical crisis, the Mari letters show them in their "infancy", scattered bands of roving mercenaries and outlaws that the local kings were trying to manage, hire, or suppress.

The following examples of texts are from the Archives Royales de Mari (ARM).

The "Donkey Slayer" Treaty (ARM II 37)

This is perhaps the most famous text concerning the Habiru found at Mari. It describes a general named Iddin-Yatum making a treaty with a band of Habiru.

It is fascinating because it details the specific ritual used to seal the deal: killing a donkey foal.

"To my lord [King Zimri-Lim] say: Thus speaks Iddin-Yatum, your servant. I have gone to the city of Ashlakka... and they have agreed to make peace. The men of Ashlakka and the Hapiru assembled. They wanted to kill a puppy and a goat [to seal the oath], but I did not agree. I insisted on the killing of a donkey foal. Thus I made peace between the Hapiru and the men of Ashlakka."

The Habiru were apparently organized enough to sign formal treaties with city-states.

The "killing of the donkey" (hayaram qatarum) was a specific West Semitic ritual for making a covenant. This links the Habiru culturally to the Amorite traditions of the region (and arguably, later biblical traditions of animal sacrifice for covenants).

The Raid Report (ARM XIV 50)

This letter comes from a governor named Yaqqim-Addu writing to King Zimri-Lim of Mari. It captures the chaotic, bandit-like nature of the Habiru when they were not employed as mercenaries.

"To my Lord say: Thus speaks Yaqqim-Addu, your servant. Regarding the Hapiru of the city of Yahmumam... Three days ago, they went out to raid in the Upper District. They captured a man... and seized 30 sheep. The day they arrived, the soldiers of the district of Zalluhan... chased after them... and they recovered the sheep, but the Hapiru fled to the mountains."

The Habiru operated exactly like the outlaws of the "Wild West." They struck rural areas (sheep, isolated men) and then fled to the "mountains" where the chariots of the King could not follow.

From this text it is obvious that the Habiru lived on the fringes, the mountains and steppes, outside the agricultural heartland.

The "Failed Soldiers" (ARM IV 50-88 context)

In the Mari archives, we often see how someone becomes a Habiru. It wasn't an ethnicity, it was a destination for failures.

In one series of letters, a general complains about soldiers deserting the King’s army.

Paraphrased Summary of ARM IV Texts

The general complains that 500 soldiers have deserted the army. They have not returned home to their families. Instead, the text notes, "they have gone over to the Hapiru."

When the pressure of the state became too much (taxes, military draft, debt), people didn't just run away, they ran to a specific group. The Habiru bands acted as a sponge for the discontented elements of the Bronze Age.

The Mercenary Wages (ARM XIII 145)

This text is a simple administrative record, but it proves that the Habiru were fully integrated into the warfare of the time as paid assets.

"Two wagons... ten sheep... [amounts of grain]... Provisions for the Hapiru who are staying in the city of Talhayum."

In this text the Habiru aren't enemies, they are guests. They are being housed and fed by the state, likely as a standing mercenary force to defend the city of Talhayum. This mirrors the biblical story of David, who took his band of "outlaws" and served the Philistine King Achish as a mercenary unit (1 Samuel 27).

Summary of the Mari Habiru

In the Mari texts, the Habiru are not yet the "swarm" that destroys civilisation (as they appear in the later Amarna letters). They are a nuisance, but a sometimes useful one. They are capable of making treaties, fighting wars, and absorbing refugees. They are a recognised, albeit dangerous, part of the social landscape.

The Nuzi Texts ( c 1450 – 1350 BC)

The Nuzi texts, of which over 5,000 have been found, detail legal contracts where individuals sell themselves into servitude to wealthy households to become Habiru, indicating it was sometimes a desperate survival strategy but offering a more secure future than joining marauding bands in the mountains.At this time Nuzi was a provincial centre of the Kingdom of Arrapha, which was a vassal to the powerful Mitanni Empire. The archives end abruptly with the destruction of the city by the Assyrians around 1350 BC.

The following texts come primarily from the archives of a wealthy Nuzi official named Tehip-tilla (and his family), who seems to have been a major employer of these destitute people.

The "Voluntary Slavery" ContractThis is the most common type of text involving Habiru. A desperate individual, often a refugee from another land, "enters" the household of a wealthy patron.

Tablet JEN 458 tells us:

"Warad-Kubi, the Habiru from the land of Assyria, has caused himself to enter into servitude (warduti) to Tehip-tilla, son of Puhi-shenni. As long as Tehip-tilla lives, Warad-Kubi shall serve him. When Tehip-tilla dies, he shall serve his son. If Warad-Kubi infringes the agreement and leaves the house of Tehip-tilla, he shall give one strong-bodied man as his substitute to Tehip-tilla. Tehip-tilla shall give food and clothing to Warad-Kubi."

Warad-Kubi is explicitly called a Habiru. He is a foreigner (from Assyria) with no legal protection. He is trading his freedom for "food and clothing." This indicates the Habiru were often starving refugees. Unlike chattel slavery (where you are property forever), Warad-Kubi has a theoretical way out. He can leave if he provides a "substitute", another man to take his place. Since a starving refugee probably couldn't afford a substitute, this was effectively a life sentence.

The "Sistership" Contract (Sale of Daughters)

These texts are crucial for understanding the future biblical laws regarding female servants. At Nuzi, you couldn't legally "sell" your daughter as a slave, so they used a legal loophole called Ahatutu ("Sistership").

Tablet HSS V 67 tells us:

"Akkul-enni, son of Hil-bishuh, has given his daughter, Beltakkad-ummi, into sistership (ahatutu) to Hurazzi, son of Ennaya. Hurazzi shall give 40 shekels of silver as her price to Akkul-enni. Hurazzi may give Beltakkad-ummi as a wife to a slave or to a free man. If she dies, Hurazzi may take her sister... Beltakkad-ummi has been given in marriage to the slave of Hurazzi."

The father "adopts" his daughter out to a wealthy man as a "sister." The wealthy man (Hurazzi) pays a "price" and gains the right to marry her off to anyone he chooses, often one of his slaves, effectively making her a slave within his household.

An Aside: Nuzi Texts versus The Bible (Exodus 21)

As a slight aside, the Nuzi texts are used by scholars to explain puzzling texts in the Bible from Genesis and Exodus.

The 15th to 14th century dating is significant because the texts reveal social and legal customs (such as adoption for inheritance, marriage contracts, and exchanging rights for food) that bear a striking resemblance to the stories of the Biblical Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) in Genesis.

However, this creates a historical puzzle. The Nuzi texts were written centuries after the traditional biblical date for the Patriarchs (c. 1800 BC). This suggests that the customs described in Genesis may have been long-standing cultural traditions in the Near East that persisted for hundreds of years.

When you compare these Nuzi tablets to the Book of Exodus, the "Law of the Hebrew Slave" suddenly makes sense as a response to these Bronze Age customs.

The Biblical law in Exodus 21:5-6 describes a slave who says, "I love my master... I will not go out free."

At Nuzi, "not going out free" was the standard contract (Tablet JEN 456). In the Bible, this status, the Habiru lifestyle of permanent dependency, was treated as an exception, not the rule. The Bible took the common Habiru practice of the time and put a 6 year term limit on it, turning a lifetime caste status into a temporary economic rehabilitation.

The Amarna Letters ( c 1360 – 1332 BC)

The Amarna letters include diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian Pharaohs Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten, and their vassal kings in Canaan (modern-day Israel, Palestine and Lebanon).

In the Late Bronze age (1550-1200 BC), Egypt controlled most of Canaan through a system of vassal city-states.

In urgent dispatches sent to Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, the chieftains of the land of Canaan speak of the Habiru as a perilous threat to their city-states.

Habiru Alliances with Canaanite Cities

For example, Rib-Hadda, the leader of the Canaanite city-state of Byblos in about 1350 BC, complains in his letter to Pharaoh:

'All my cities which are situated in the mountains or along the sea have sided with the Habiru people'.

In other words, the outlying citizenry of Rib-Hadda's kingdom have identified themselves (in the eyes of Rib-Hadda) with the unworthy and disloyal 'Habiru,' and thus are to be considered as enemies of the crown.

Accusations of Employing Habiru Mercenaries

In another Armana letter, we see a message from Milkilu to the Pharoah (probably Akhenaten). Milkilu was the mayor of the Land of Gazru, roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in about 1350 BC. Milkilu is accused of being a rebel and of employing Habiru mercenaries. Suwardata was probably the king of the Canaanite city-state of Gath which was close to the border with Judah. Yanhamu was an Egyptian commissioner who travelled between the Canaanite city states reporting back to the Pharoah on city or regional accounts and any external affairs likely to be of interest or concern to the Pharoah. The letter reads:

'Say to the king, my lord, my god, my Sun: Message of Milkilu, your servant, the dirt at your feet. I fall at the feet of the king, my Lord, 7 times and 7 times. May the king, my lord, know that the war against me and against Suwardata is severe. So may the king, my lord, save his land from the power of the Apiru. Otherwise, may the king, my lord, send chariots to fetch us lest our servants kill us. Moreover, may the king, my lord, ask Yanhamu, his servant, about what is being done in his land.'

A second letter from Milkilu reads:

'Say to the king, my lord, my god, my Sun: Message of Milkilu, your servant, the dirt at your feet. I fall at the feet of the king, my Lord, 7 times and 7 times. May the king, my lord, know the deeds that Yanhamu keeps doing to me since I left the king, my lord. He indeed wants 2000 shekels of silver from me, and he says to me: Hand over your wife and your sons, or I will kill [you].May the king know of this deed, and may the king, my lord, send chariots and fetch me to himself lest I perish.'

Yanhamu was evidently not the most honest of commissioners.

Facing the Habiru and the Sa-Gaz

Around the same time, Etakkama, king of Kadesh, wrote to the Pharoah.

'Behold, Namyawaza has surrendered all the cities of the king, my lord to the Sa-Gaz in the land of Kadesh and in Ubi. But I will go, and if thy gods and thy sun go before me, I will bring back the cities to the king, my lord, from the Habiri, to show myself subject to him; and I will expel the Sa-Gaz.'

Namyawaza was a powerful ruler, thought to have been the king of Damascus. Sa-Gaz, a word that simply means trespassers, were a group of Akkadians.

The Widespread Influence of the Habiru

Zimrida, the king of Sidon, similarly wrote to Akhenaten:

'All my cities which the king has given into my hand, have come into the hand of the Habiri."

Idrimi: A Habiru Leader Who Became King of Alalakh

Idrimi was the founding king of a town called Alalakh situated near Antioch in present day Turkiye. He is thought to have ruled Alalakh from about 1450 BC. Alalakh was a vassal city-state that sat at a strategic crossroads between the major powers of the time, the Hittites (to the north), the Mitanni (to the east), and Egypt (to the south).

According to an inscription on a statue of Idrimi, he fled his native city of Emar and joined the "Habiru people" in "Ammija in the land of Canaan." After living among them for seven years, he led his Habiru warriors in a successful attack by sea on Alalakh, where he became king. A record from Alalakh tells of a band of 1,436 men, eighty of which were charioteers and 1,006 were shananu, probably archers. It is unclear whether the latter record described Idrimi's force or not. Notice that Idrimi attacked from the sea.

This serves as the only first-person account of a king admitting he was once a member of this "lawless" social class.

Canaanite Kings Hiring and Fighting the Habiru

The Canaanite kings supplemented their own forces with Habiru and, on occasion, had to subdue wandering bands of Habiru themselves.

From Habiru Outlaw to Philistine Mercenary

Perhaps the most famous Habiru was called David, you may have heard of him. When forced to leave Saul's court for fear of being killed in about 1018 BC, David returned to his Habiru brothers in the desert and raised an army of about six hundred that he then hired out to various Philistine kings.

The Brutal Practices of the Habiru

The Habiru had a nasty habit of cutting the arms off their opponents to prove their worth to their paymasters. To be fair, this practice was not confined to Habiru mercenaries, there are records of Egyptian and Hittite troops doing the same thing.

The "Hebrew" Connection

The most controversial and debated aspect of the Habiru is their connection to the biblical Hebrews (Ivri).

Etymologically, Habiru and Ivri (Hebrew) are strikingly similar. For a long time, scholars believed the Habiru were the Israelites conquering Canaan under Joshua. Most modern archaeologists and historians do not equate the two directly, but they acknowledge a sociological connection.

The Habiru were active centuries before the emergence of a distinct Israelite identity, and they were found all over the Middle East, not just in Canaan. The early Israelites likely emerged from the Habiru social class. The biblical description of early Hebrews as nomadic, distinct from the urban Canaanites, living in the hill country, matches the description of the Habiru.

When the Bible refers to "Hebrews" (Ivrim) in early texts (as in the laws for a "Hebrew Slave" mentioned above), it often refers to a social class of landless people, reflecting the Habiru reality.

The End of the Habiru

The Habiru phenomenon was strictly tied to the political structure of the Bronze Age.

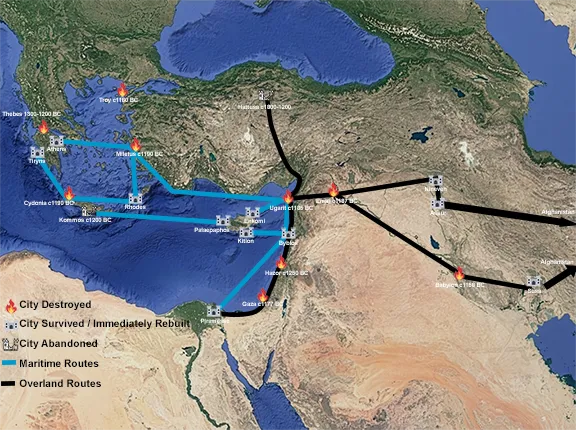

Around 1177 BC, the Late Bronze Age Collapse was in full flow. The great empires were retreating or had fallen, and the palace economies were being destroyed.

With the collapse of the central powers, the "fringes" became the new centres. The Habiru stopped being outsiders and settled down, coalescing into the new ethnic nation-states of the Iron Age, the Ammonites, the Edomites, the Arameans, and the Israelites.

The Habiru and the Collapse of the Bronze Age Civilisations

The Habiru were therefore the symptoms of a breaking system, not the overriding cause of the Bronze Age collapse. They were the dispossessed and the adventurous who chose the freedom of the wilderness over the servitude of the palace. While they were "lawless" to the kings of the time, they were the ancestors of the new nations that would rise from the ashes of the Bronze Age.

As an internal threat to the small world system created by the Great Powers, (see ‘The Development of Diplomacy Between Bronze Age Empires in the Middle East’), their activities when combined with the external threat of invasions and immigrations of a separate group of marauders, the ‘Sea Peoples’, created a significant catalyst for the calamitous events that were unfolding at the time.

References

Chiera, Edward (1927-1934). Joint Expedition with the Iraq Museum at Nuzi.

Cline, Eric H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press.

Drews, Robert (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton University Press.

Durand, Jean-Marie (1997-2000). Les Documents épistolaires du palais de Mari. (Standard French edition of the Archives Royales de Mari - ARM).

Eichler, Barry L. (1973). Indenture at Nuzi: The Personal Tidennutu Contract and its Mesopotamian Analogues. Yale University Press.

Greenberg, Moshe (1955). The Hab/piru. American Oriental Society.

Greenstein, Edward L., and Marcus, David (1976). "The Accadian Inscription of Idrimi." Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society, 8(1).

Heimpel, Wolfgang (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation. Eisenbrauns.

Lemche, Niels Peter (1992). "The Habiru/Apiru," in The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Doubleday.

Malamat, Abraham (1992). Mari and the Early Israelite Experience. Oxford University Press.

Moran, William L. (1992). The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Na’aman, Nadav (1986). "Habiru and Hebrews: The Transfer of a Social Term to the Literary Sphere." Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 45(4).

Smith, Sidney (1949). The Statue of Idri-mi. British Institute of Archaeology in Ankara.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron