Civilisations that Collapsed

Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

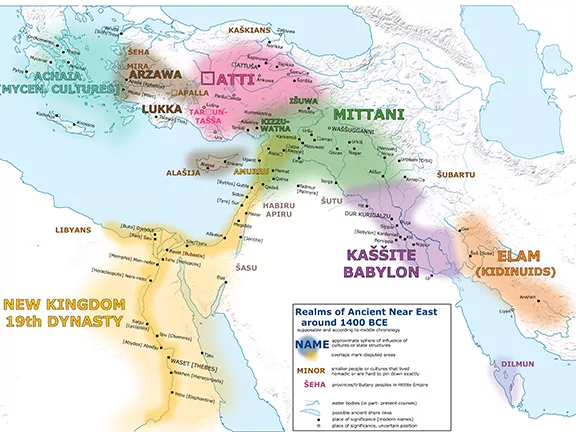

The Late Bronze Age Middle East was dominated by a handful of powerful kingdoms stretching from Anatolia through Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. These Great Kingdoms, while sharing similarities in governance, also exhibited significant differences.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-15 | Last Updated 2025-11-25 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 3,899 times

How to manage a vassal state

A Hodgepodge of Languages and Ethnicities

At the heart of each kingdom lay its core territory, the locus of power and direct rule. Here resided the aristocracy, the king's administration, and the backbone of his military. These core inhabitants considered themselves superior to those in conquered lands, forming a distinct societal hierarchy.

Despite a shared region, these kingdoms were a jumble of languages and ethnicities. Official tongues varied, often differing from the most widely spoken vernacular. Moreover, the ruling elite frequently hailed from backgrounds distinct from the broader populace. For instance, Kassite foreigners governed Babylon, while the Hittite dynasty's origins remain uncertain and potentially unrelated to the region's dominant ethnic group. Mitanni, too, exhibited this pattern of a ruling class set apart from the general population.

Ancient documents have allowed us to examine how some of the ‘Great Kings’, those from Egypt, the Land of Hatti, Assyria and Mitanni, handled their affairs with vassal states.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Relations Between Overlord and Vassal

Beyond their core territories, the Great Kings exerted dominion over a complex network of subject lands, typically acquired through military conquest. These territories were composed of vassal kingdoms and principalities, largely governed by local rulers. Provided they fulfilled their obligations, these rulers enjoyed considerable autonomy in managing their states.

Relations between overlord and vassal in the Land of Hatti

Hittite treaties explicitly outlined the reciprocal duties of overlord and vassal, transforming the relationship into a personal contract between the Great King and the subject ruler rather than a formal agreement between states. Military aid and annual tribute were standard obligations for vassals, while the overlord pledged protection from external threats and ensured the succession of the vassal's dynasty.

Overlord Intervention in the Land of Hatti

The level of overlord intervention in vassal affairs fluctuated across kingdoms and even within individual states. Hittite kings adopted a largely hands-off approach, rarely installing their own administrators in subject territories. This policy, driven primarily by logistical constraints rather than diplomatic finesse, limited the Hittite military presence to areas of critical strategic importance or acute instability. The constant demand for troops to secure the homeland and wage offensive campaigns further discouraged the prolonged stationing of garrisons in vassal lands.

Relations between overlord and vassal in Egypt

The nature of Egyptian-vassal relations remains less clear due to a scarcity of surviving documents. While Egyptian officials were more directly involved in local administration compared to their Hittite counterparts, the absence of formal contracts may have fostered misunderstandings. The frustrations expressed by vassal rulers in the Amarna letters, written between 1360 and 1332 BC, suggest they felt shortchanged on promised support and resources, highlighting potential shortcomings in Egypt's imperial management.

Despite the grievances aired in the Amarna letters, not all complaints fell on deaf ears. Pharaohs occasionally responded with stern rebukes, accusing vassal rulers of excessive whining, inaction, and insubordination. Formal agreements detailing the rights and responsibilities of both parties might have prevented such misunderstandings and strengthened the overlord-vassal bond.

Overlord Intervention in Egypt

In contrast to the Hittite approach, Egypt maintained a more direct presence in its Syrian and Palestinian dominions. The region was divided into up to four administrative provinces, each with a blend of Egyptian and local officials. While indigenous royal families retained authority and existing administrative structures largely persisted, Egyptian oversight was pronounced. Commissioners, often Canaanites but primarily Egyptians, were tasked with tax collection and general supervision of local rulers. These officials held itinerant roles, responsible for multiple towns within a district. Nubia was the exception. Here the old political structures were disbanded, and the region was placed under the direct administration of an Egyptian viceroy.

Overarching control rested with the "overseer of all northern lands," the pharaoh's chief representative.

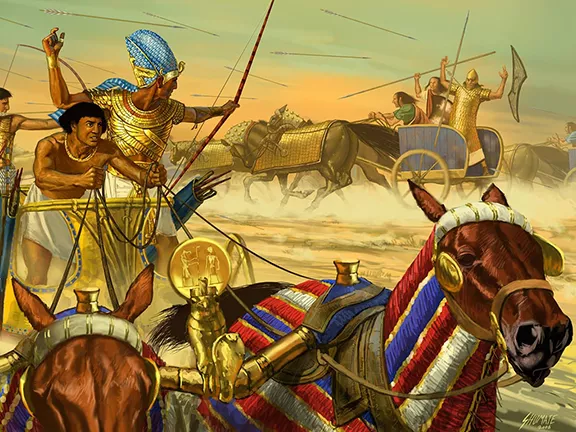

To solidify Egyptian authority, fortified garrison cities like Gaza, Kumidi, Sumur, Megiddo, and Beth Shan housed resident Egyptian governors. These officials held both civil and military powers, though dedicated military commanders led the stationed troops that consisted of contingents of chariotry and infantry or detachments of archers. The burden of provisioning these forces fell on the local rulers, underscoring their subordinate position.

'When the troops and chariots of my lord have come here,' wrote Akizzi, king of Qatna, to Akhenaten, 'food, strong drink, oxen, sheep, and goats, honey and oil, were produced for the troops and chariots of my lord.'

The extent and permanence of the Egyptian presence in these territories remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, it undoubtedly created friction between the Egyptian administration and local rulers and populations, as evidenced in the Amarna letters. Paradoxically, some local leaders sought Egyptian military support for internal security or external defence.

While Egyptian rule brought certain advantages, it undeniably diminished the status of the once independent Syrian-Palestinian kingdoms. The pharaoh emphasised the absolute subservience of local leaders, reducing them to mere "mayors" (hazannu) in the eyes of the Egyptian administration. Their authority was equated with that of Egyptian local officials, burdened with identical tax and service obligations. Professor Redford remarks that they were “thus demoted to the status of the local mayors in Egypt, and the same taxes and services were demanded from them as from their Egyptian counterparts”. The court administration treated them as Egyptian mayors in one important aspect: they held full responsibility for everything that happened in the city-state in their charge.

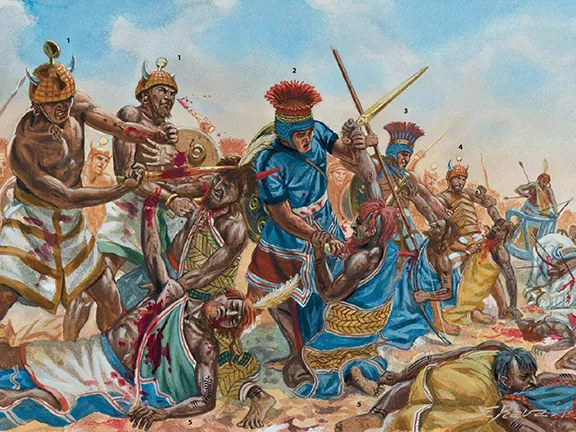

The pharaoh viewed the multitude of petty Asiatic rulers with disdain, regarding them as unworthy of greater recognition. According to Tuthmosis III, no less than 300 princes, mainly from Palestine, fought against him at the battle of Megiddo (between 1482 and 1457 BC, accounts vary), and they were soundly beaten.

To ensure loyalty, the sons of local rulers were held hostage in Egypt, ostensibly for education or indoctrination into Egyptian customs prior to the assumption of power in the area they came from, but primarily as a guarantee of their fathers' compliance. This practice underscored the subordinate status of the Syrian-Palestinian kingdoms and their rulers.

The practice had begun with Tuthmosis III (1479 to 1425 BC), who tells us, 'Now the children of the chiefs and their brothers were brought to be hostages in Egypt; and as for any of these chiefs that died, His Majesty used to have his son assume his post.'

Elevated Status for the Few

Certain of the Great King's vassals were granted elevated status and greater autonomy by their overlords, particularly those demonstrating strategic value in territorial expansion or defence.

Elevated Status for the Few in Mitanni

Idrimi, king of Alalakh from about 1490 until 1465 BC, is a good example. A former exiled ruler, he was reinstated with Mitannian backing after Parattarna conquered Aleppo.

Idrimi's inscription offers invaluable insights into his reign. His rapid expansion, marked by the conquest of seven towns bordering Hittite territory, demonstrates his ambition and military prowess. His subsequent treaty with Kizzuwadna, a strategically vital kingdom, was executed under Parattarna's authority, underscoring the Mitannian king's support. This alliance significantly amplified Mitanni's influence in Anatolia, aligning perfectly with Parattarna's imperial aspirations. The extent to which Parattarna initiated or merely endorsed Idrimi's aggressive foreign policy remains open to debate, but it is clear that the two rulers shared a common goal of expanding Mitannian dominion.

Elevated Status for the Few in the Land of Hatti

Suppiluliuma I's (c1350 – 1322 BC) support of the Mitannian prince Kili-Teshub, later known as Shattiwaza, mirrored Parattarna's backing of Idrimi. By restoring the Mitannian royal line, Suppiluliuma, king of the Hittites, ensured a buffer state against the growing Assyrian threat. The designation of Mitanni as a kuirwana, or protectorate, signified a special status elevating Shattiwaza above the rank of a typical vassal. This privileged position was underscored by ceremonial honours, tax exemptions, and limited territorial gains. However, the illusion of independence was deceptive, Shattiwaza remained tightly bound to the Hittite chariot, forbidden from establishing autonomous foreign relations.

Kizzuwadna's history echoed a similar pattern of fluctuating alliances and shifting allegiances. Once a part of the Hittite Old Kingdom in southeastern Anatolia, it achieved independence before aligning with both Mitanni and Hatti at different junctures. Ultimately, it too was absorbed into the Hittite empire as a kuirwana and, eventually, a fully integrated province.

Elevated Status for the Few in Hanigalbat

Across the Euphrates, what was left of the former Mitanni kingdom was known as Hanigalbat. Hanigalbat mirrored the trajectory of Kizzuwadna and Mitanni. Initially a theoretically independent ally of Hatti with kuirwana status, it succumbed to growing Assyrian influence. Following King Shattuara I's ill-advised and ill-fated attack on Assyria, Hanigalbat was reduced to vassal status by the Assyrian king Adad- nirari I. Shattuara's son Wasashatta's later led a rebellion that met a similar fate, culminating in Adad-nirari I's annexation of the kingdom and the establishment of an Assyrian royal residence in Taide.

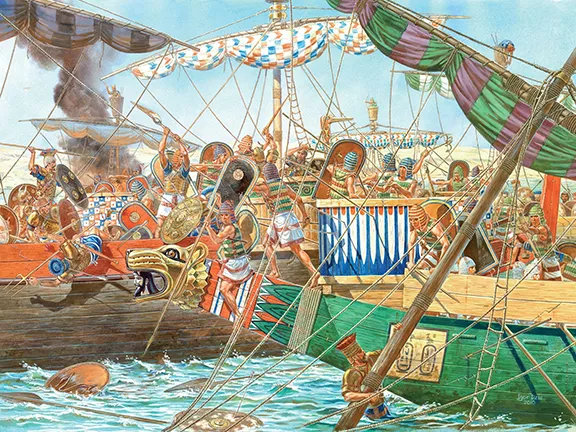

Introducing the Concept of Viceroyalty in Egypt

The pattern of conquest and annexation was similarly evident in Egypt's southern expansion. Kamose (c 1555 to 1550 BC), the last king of the Seventeenth Dynasty, initiated incursions into Kush, a Hyksos ally. His successors, Amenhotep I and Thutmosis I, expanded upon these campaigns, resulting in the complete annexation of Nubia. This marked a stark contrast to Egypt's approach in Asia, where a complex system of vassal kingdoms with varying degrees of autonomy persisted.

Egypt's southern territories were under the direct control of a high-ranking official, the Viceroy of Kush. This position, with its title of "King's Son of Kush and Overseer of the Southern Lands," underscored the importance of the region to the Egyptian crown. The viceroy's jurisdiction extended from the third nome of Upper Egypt to Kurgus, encompassing the entirety of Lower and Upper Nubia.

Introducing the Concept of Viceroyalty in the Land of Hatti

A parallel development occurred in the Hittite realm. Under Suppiluliuma I, the concept of viceroyalty was introduced with the appointment of his sons to viceregal posts to govern Carchemish and Aleppo. This marked a significant departure from previous Hittite policy, as it established direct imperial rule over territories outside the Anatolian homeland. These viceroys, always members of the royal family, wielded substantial authority in Syria, overseeing military, judicial, and political matters. They often acted as the king's direct representatives in dealing with local vassal rulers.

The practice of appointing royal family members as viceroys was not exclusive to the Hittites and Egyptians.

Introducing the Concept of Viceroyalty in Assyria

About 1796 BC, Shamshi-Adad I had installed his sons, Ishme-Dagan and Yasmah-Addu, as governors of Ekallatum and Mari, respectively. These strategic placements underscored the importance of these cities within the Assyrian Empire. Both the Hittite and Assyrian examples highlight a deliberate strategy to solidify control over key regions while simultaneously elevating the status of the appointed cities.

Kassite Babylon the Exception

In contrast to the more expansive empires of Egypt and the Hittites, Babylonia was a geographically compact state. Under Kassite rule (from about 1595 to 1155 BC), the kingdom was divided into administrative provinces governed by appointed officials. These governors were based in major urban centres and held broad responsibilities. Their duties encompassed tax collection, military provisioning, and public works projects, including infrastructure development and maintenance.

While the Babylonian system lacked the formal structure of viceroyalties found in Egypt and the Hittite and Assyrian empires, the governors nonetheless wielded considerable authority within their respective provinces. Their role was crucial in maintaining the effective administration of the kingdom. Inscriptions on boundary stones, known as kudurrus, reveal a Kassite practice of granting land to a diverse group of individuals, including courtiers, priests, military officers, and even royalty. This strategy, adopted by Hittite kings as well, served multiple purposes. It rewarded loyal service, ensured continued allegiance, and maximised land productivity, thereby increasing royal revenue. Exceptions were made for grantees explicitly exempted from taxation.

Babylonia flourished under the stable and centralised rule of the Kassite dynasty. Its compact territory and the rulers' apparent lack of expansionist ambitions shielded it from the complexities and challenges faced by its contemporaries in managing far-flung empires. The Kassite kings enjoyed the prestige of peer status among other great powers without the immense military expenditures required to maintain such standing. While tensions and occasional conflicts with neighbouring Assyria emerged, Babylonia's overall stability and prosperity endured until the end of the Late Bronze Age.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC

13: Beginning of the End 1400 - 1387 BC 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron