Civilisations that Collapsed

Beginning of the End for the Bronze Age Civilisations 1400 - 1387 BC

In this article we look at the history of the bronze age civilisations in the Middle East from the beginning of the 14th century BC until the first cracks start to appear during the Assuwa revolution.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-08-20 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Civilisations that Collapsed

This article has been visited 3,137 times

Middle East about 1400 BC

When did the Bronze Age Collapse in the Middle East begin?

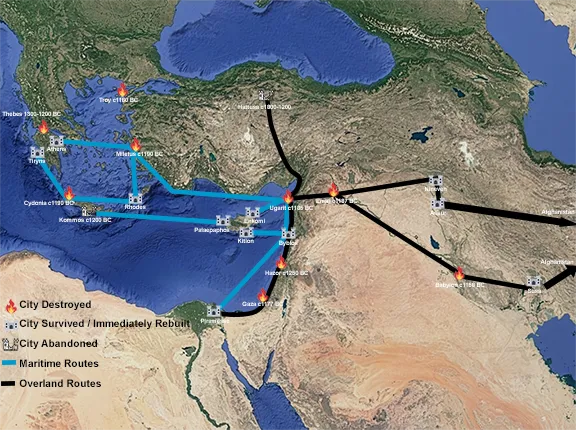

The Bronze Age decline starts towards the end of the 15th century BC with the ascendancy of the Hittite Empire as the region's dominant force. Tudhaliya II, who assumed the throne in approximately 1425 BC under contentious circumstances, ushered in a new era for the Hittites. This period was marked by an aggressive expansionist policy, extending Hittite influence westward into Anatolia and southward into Syria.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

The Great Powers in 1400 BC

The Hittites

For nearly two centuries (circa 1400-1200 BC), the Hittite Empire stood as a preeminent power, fostering unprecedented interaction with other Near Eastern kingdoms. Yet, this period was characterized by significant fluctuations in fortune. While Tudhaliya's military conquests in Syria and western Anatolia bolstered Hatti's international standing, the empire's foundation remained precarious. Even under the capable leadership of his successor, Arnuwanda, the kingdom grappled with internal challenges.

In a fragment of a tablet found at Hattusa, we read of a treaty between Thutmose III or Amenhotep II of Egypt, and Tudhaliya II. It is known as the Kurustama Treaty and dealt with the relocation of some of the population of Kurustama from Hittite into Egyptian territory, in other words, forced labour. We can deduce that, at the beginning of the 14th century BC, relations between the Hittites and Egypt were at least cordial.

The Kingdom of Mitanni

Towards the end of the 15th century BC, faced with a potential Hittite threat to the north, Mitannian king Artatama I, negotiated an alliance with the Pharaoh Amenhotep II of Egypt to the south. By the terms of the treaty, the frontier between the two kingdoms gave Egypt control northwards to Kadesh on the Orontes River, and to Amurru and Ugarit along the coast. All territory beyond these was conceded to the Kingdom of Mitanni. Conflicts, alliances and treaties between neighbouring powers and Mitanni are reasonably accurately recorded, most often by the opposition rather than Mitanni. To date (2024 AD), the capital of the Mitanni Empire, Wassukkani has not been found and no royal annals or chronicles have been found at any of the excavated sites. Most of what we know about Mitanni therefore comes from texts found in neighbouring kingdoms.

Egyptian New Kingdom

By 1400 BC, Egypt under the new pharaoh, Thutmose IV, was almost at its height of territorial expansion, power, wealth, and status. Internally, the Egyptians ruled from Kush in the south to the Nile Delta. Externally, their vassal territories covered Sinai, Canaan, and western Syria, to the negotiated border with Mitanni at Kadesh.

Kassite Babylonians

The Kassites, a mountain people from the Zagros range (present-day Iran), emerged as unlikely inheritors of Babylonian power. Seizing the opportunity created by the collapse of the Old Babylonian Empire, they established their own dynasty in Babylon, ushering in the Middle Babylonian period, also known as the Kassite Dynasty. The collapse of the First Sealand dynasty around 1460 BC left a political void subsequently filled by the Kassites. The Kassite dynasty reached its zenith under Kurigalzu I in the early-fourteenth century BC. Babylon itself was renamed "Karanduniash".

The Aspiring Great Powers in 1400 BC

Mycenaean Civilisation

In 1400 BC, the Mycenaeans were approaching the zenith of their powers and territorial extent. Fortifications employing a technique known as Cyclopean masonry were built around 1400 BC at Mycenae and Tiryns. Midea, Pylos, Athens, Eleusis, Thebes, Orchomenos, and Iolcos (the northernmost Mycenaean centre) also saw palace construction.

They, and their predecessors, the Minoans, had long had a fruitful trading relationship with Egypt. By the end of the Hyksos period in Egypt, about 1530 BC, there was a flourishing Minoan colony at Tell el-Dab'a in the Nile delta. By the time of Thutmose III, about 1425 BC, the city had decorated palace structures in the Mycenaean style and Mycenaean stirrup jars from this time have been found as far south as Thebes and at Tell el Amarna, later famous for the Amarna letters. In Thebes, amongst the painted scenes of daily life found in the tombs of nobles, we find depictions of envoys from Mycenae bringing tributes and gifts to Egypt.

The Mycenaean civilisation reached its peak about 1350 BC, by which time its territory consisted of palatial states on mainland Greece, Crete, parts of western Anatolia and the Aegean islands as far as Rhodes. The palatial states boasted a complex administrative system. Work was divided among specialized departments, each handling specific trades and tasks. At the head of this society was the king, known as wanax.

Elam

Elam was a civilisation bordering the northeastern coast of the Persian Gulf in what is now the southwest of Iran. The society was somewhat isolated from the rest of the Middle East, with just a short border in the northwest adjoining Babylonia.

1400 BC ushered in the Ighalkid Dynasty that was to last two hundred years. Elam had forged a profitable trade network that extended down the Persian Gulf and east as far as the Indus Valley civilisation which made it an attractive target for the adjoining power, the Kassite Babylonians. In 1400 BC, Elam was ruled by the first of the Igihalkid dynasty, Igi-halki, who probably usurped the throne. Most of the references to the Kingdom of Elam come from texts from neighbouring powers, very few native texts have so far been found. The regnal dates during the Igihalkid dynasty are very tentative, those of the succeeding Shutrukid dynasty from c 1200 BC are more accurate.

Assyria

Assyria was yet to re-emerge as a force in the region being confined to the city of Assur, a vassal city-state of Mitanni. That did not stop them posing a threat to the Kassite Babylonians to the south or Mitanni itself.

Arzawa

Arzawa was an independent region in western Anatolia that consisted of a capital, Apasa (later Ephesus), with a surrounding territory of small states, Mira, Hapalla, Wilusa (Troy), and the Seha River Land. Apasa and the lesser states were all ruled by kings in a state-level society that also formed a loose military confederation. Never entirely united, Arzawa never quite made it as one of the 'Great Powers', although it came close as we shall see.

During the reign of Thutmose III (1479 BC to 1425 BC), Arzawa is mentioned for the first time in Egyptian texts. In an inscription at the Temple of Karnak, Thutmose boasts of his conquest of over one hundred territories, including Arzawa from where he took 175 prisoners.

In the diaries from the royal shipyard at Perunefer, we are informed that Arzawans are employed as shipbuilders during the same period. One such worker is simply called 'the Arzawan' who is also named in a papyrus in the British Museum where his position is given as 'chief craftsman', or 'head carpenter'.

Kings in 1400 BC

Egypt Pharaoh Amenhotep II

HittitesTudhaliya II

Kassite Babylon Kadashman-Harbe I

Mitanni Artatama I

Assyria Ashur-nadin-ahhe II

c 1400 BC Kurigalzu I becomes King of Babylon (until c 1375 BC)

The exact date Kurigalzu succeeded his father, Kadashman-Harbe I, is not known.

c 1400 BC Thutmose IV becomes Pharoah of Egypt (until c 1390 BC)

At the turn of the century, Thutmose IV succeeded Amenhotep II as Pharaoh of Egypt. He inherited a kingdom at the peak of its powers and extent. The date of his accession is not known exactly.

Little is known about the ten year reign of Thutmose IV apart from his continued efforts to maintain friendly relations with Mitanni by marrying a Mitannian princess, and we only know that from one of the Armana letters written decades later by the Mitannian king Tushratta in a letter to Pharoah Akhenaten.

'When [Menkheperure], the father of Nimmureya (i.e.,Amenhotep III) wrote to Artatama, my grandfather, he asked for the daughter of my grandfather, the sister of my father. He wrote 5, 6 times, but he did not give her. When he wrote my grandfather 7 times, then only under such pressure, did he give her.

The letter implies that Thutmose IV had to request a bride from Artatama I of Mitanni no less than seven times before Artatama agreed to the union.

Thutmose IV had inherited a religious problem from his father, Thutmose III. Of the many gods worshipped by the Egyptians, Amun was one of the most powerful and the Priests of Amun were the dominant priesthood. Thutmose III donated riches and land to the Priests of Amun to such an extent that their power rivalled that of the pharaoh himself. To curb their power, Thutmose IV promoted the solar deity, Aten and pronounced himself the sun god Ra, the creator of life. This religious conflict was to have dire consequences when his grandson, Amenhotep IV came to the throne.

c 1390 BC Pahir-ishshan I becomes King of Elam (until c 1380)

If Elam played any role in the interactions between the 'Great Powers' of the Middle East during the first quarter of the 13th century, any record of it has been lost or not yet found.

c 1390 BC Arnuwanda I becomes King of the Hittites

In an unusual arrangement, Arnuwanda co-ruled with his father in law, Tudhaliya II, for up to twelve years. This arrangement probably set a precedent, repeated a century later by Muwatalli II.

The Assuwa Rebellion

In those early years, the two kings led campaigns against Arzawa, a loose confederation of states in western Anatolia that included Mira, Hapalla, Wilusa (probably the city of Troy), and the Seha River Lands. About 1400 BC, Arzawa was joined by other states in western Anatolia to make a confederation of twenty two states in total known as Assuwa all dedicated to the overthrow of the Hittite Empire. The annals of Tudhaliya state:

'But when I turned back to Hattusa, then against me these lands declared war: [...]lugga, Kispuwa, Unaliya, [-], Dura, Halluwa, Huwallusiya, Karakisa, Dunda, Adadura, Parista, [ ], [-]waa, Warsiya, Kuruppiya, [-]luissa, Alatra, Mount Pahurina, Pasuhalta, [-], Wilusiya, Taruisa. [These lands] with their warriors assembled themselves ......... and drew up their army opposite me.'

The Assuwa confederation may have been supported by the Ahhiyawans (Mycenaean Greeks), a supposition based on the finding of a Mycenaean style sword found at Hattusa that bore an inscription suggesting that is was taken from an Assuwan soldier and then given as an offering to the Hittite storm god and, as we shall see below, a short reference to Ahhiyawa in a Hittite text.

In any case, we know of at least two campaigns against Arzawa when the two kings defeated Kupanta-Kurunta of Arzawa and it is during the second of those campaigns that the irrepressible warlord Madduwatta makes an appearance. He is known solely from a Hittite text called 'The Indictment of Madduwatta', the text of which is biased towards the Hittite view but gives an idea of the upheavals and political shenanigans occurring in Anatolia in the first quarter of the 14th century BC. It also gives an insight into the problems the Bronze Age kings had when dealing with unruly, ambitious and duplicitous vassals.

The Rebel Madduwatta

In the Indictment, Madduwatta is described only as a 'man of importance' in one of the (unnamed) city states in western Anatolia. About 1400 BC, during the sole reign of Tudhaliya, Madduwatta was attacked by Attarissiya, an Ahhiyawan warlord. Madduwatta fled to the protection of Tudhaliya to whom he gave an oath of allegiance and was then installed as ruler of Zippasia and the Siyante River Land (possibly called Seha River Lands in other texts). He was forbidden to establish diplomatic relations or take military action without the authority of the Hittite king. Madduwatta was not about to let those terms stop him.

Soon after the appointment of Arnuwanda as joint ruler of the Hittite Empire, Madduwatta embarked on a disastrous campaign against Kupanta-Kurunta. The Hittites had to send an army to rescue Madduwatta (probably the second Hittite campaign against Arzawa).

Returned to Zippasia, Madduwatta chose to turn a blind eye towards an incursion by his old foe, Attarissiya and again the Hittites had to send an army to bail him out. There is a suggestion that Madduwatta gave away the position of the Hittite troops to Attarissiya resulting in their defeat.

Undeterred Madduwatta turned his attention to Hittite vassal states in southwestern Anatolia, with rather more success, carving out for himself a small kingdom. He subjugated Hapalla and a number of unidentified territories, Iiyalanti, Zumarri and Wallarimma that were probably part of the neighbouring state of Lukka.

Madduwatta claimed that he was only acting in good faith because Hapalla was intending to rebel against Hittite overlordship.

Arnuwanda, who by now had had enough of his uncontrollable servant, demanded Madduwatta's extradition that was, predictably, ignored. Madduwatta went on the incite anti-Hittite rebellions in other Hittite vassal states.

The indictment recalls,

'Then because Madduwatta did not go to Dalauwa for battle, but in fact wrote away to the people of Dalauwa (saying): '[The troops] of Hatti have just gone to Hinduwa for battle. Block the road before them and attack them!'... 'They proceeded to block the way [of our] troops and routed them. They killed Kisnapili and Partahulla. But [Madduwatta] laughed out loud about them.'

Having established himself through military means, Madduwatta decided to use diplomacy to entrench his position and came to an agreement with his two long time enemies, Kupanta-Kurunta and Attarissiya, after all, they were all now on the same side.

Madduwatta offered to send his daughter to Kupanta-Kurunta to be his wife. Whether the offer was accepted is not known.

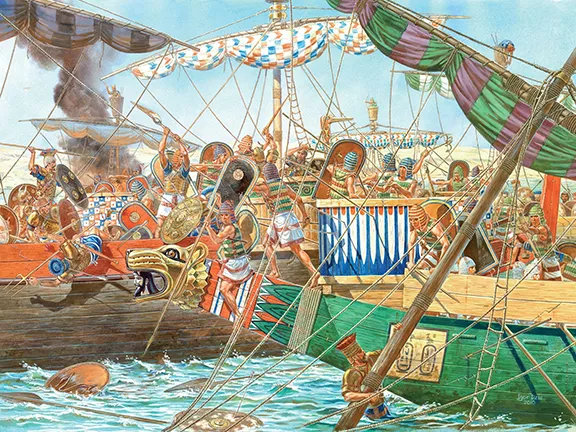

More seriously, Madduwatta then allied himself with Attarissiya and set sail for Alashya (Cyprus), an island considered by the Hittites to be their own. Having apparently taken the island, Madduwatta tried to distance himself from the affair, claiming he did not know the island belonged to the Hittite king.

'Madduwatta said thus: ...the father of his Majesty [had never informed] me, [nor] had his Majesty ever informed [me] (thus): ?The land of Alasiya is mine, recognize it as such!?'

What became of Madduwatta is not recorded.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse?

1: Did the Bronze Age Civilisations Collapse? 2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks

2: The Rise of Empires and Trading Networks 3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC

3: The First Global Trading Network c 2000 - 1700 BC 4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations

4: Late Bronze Age Civilisations 5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age

5: Managing Vassal States during the Bronze Age 6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires

6: Diplomacy between Bronze Age Empires 7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club

7: The Bronze Age Great Powers Club 8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins

8: When Diplomacy Ends, War Begins 9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event

9: The 3.2k-Year BP Event 10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru

10: Bronze Age Mercenaries - The Habiru 11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy

11: The Trojan War and the Battle of Troy 12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples

12: The Bronze Age Sea Peoples 14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC

14: Marriages and Alliances 1387 - 1360 BC 15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni

15: The Collapse of the Kingdom of Mitanni 16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire

16: The Collapse of the Hittite Empire 17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks

17: The Fall of Bronze Age Trading Networks 18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron

18: The Transition from Bronze to Iron