Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

Rochelongue Underwater Site: Discovery, Finds & Early Iron Age Trade

The Rochelongue underwater site off the coast of France is a significant Early Iron Age find. Learn about its discovery, the diverse metallic artifacts recovered (copper, bronze, weapons, jewellery), and the debate surrounding its purpose as a shipwreck or votive deposit, highlighting ancient Mediterranean trade and cultural interactions.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-04-14 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 2,360 times

Cap d'Agde

Introduction

The Rochelongue underwater site, situated off the Rochelongue reef near Cap d'Agde in West Languedoc, France, represents a significant archaeological discovery from the Early Iron Age (circa 7th-6th centuries BCE). Excavated following its initial discovery in 1964, the site has revealed a substantial collection of metallic objects, prompting ongoing scholarly debate about its nature as a shipwreck, a votive deposit, or something in between.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Where is the Rochelongue underwater site?

The Rochelongue underwater site was discovered in West Languedoc (France). More specifically, it is located on the Rochelongue reef off Cap d'Agde.

About the Rochelongue underwater site

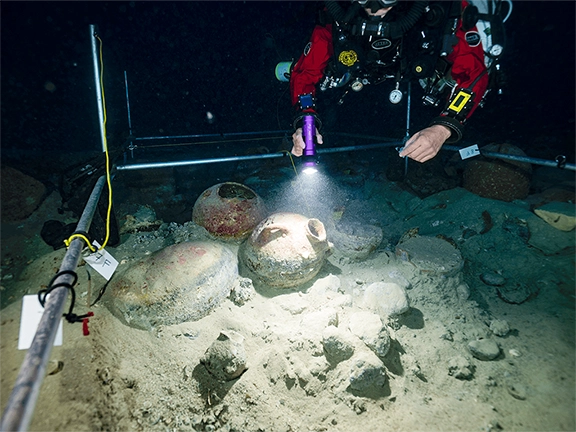

The site is situated at a depth of 6 - 8 m and near the rocky platform of Pointe Rochelongue, which is flanked by the mouth of the Herault River to the west and the promontory of Cap d'Agde to the east. Mont Saint-Loup and the islet of Brescou are also located nearby. The reef itself is formed by a basaltic outcrop.

Who excavated the Rochelongue deposit site?

The Rochelongue underwater site was discovered in 1964 by Andre Bouscaras, who was a dedicated diver and shipwreck enthusiast. The site was then subjected to a number of archaeological investigations between 1964 and 1968, and again in 1970.

The absence of wooden hull remains, rope, rigging elements, or other typical shipwreck equipment has led some scholars, such as Jean Gasco, to suggest that the site represents a votive deposit.

When were the Rochelongue deposits made?

The material assemblage found at the site allows for a chronological estimation:

The site is generally dated to the end of the seventh or the first quarter of the sixth centuries B.C.

Artefacts identified as Etruscan, Greek, Phoenician, or local have been dated anywhere from the 9th to the 6th century B.C.

The site is closely linked to the local Late Bronze Age IIIb (ca. 900 - 800 B.C.) to Early Iron Age (ca. 725 - 575 B.C.) cultural horizon, known as the 'Launacien'.

Fibulae from the site have been estimated to date from the second half of the 7th century to the first half of the 6th century B.C.

A 'Fleury' type belt buckle found at Rochelongue is similar to decorated belt buckle types found in the Iberian Peninsula that are dated between 625 and 575 B.C.

Therefore, while we cannot pinpoint a specific sinking or depositional date, the evidence suggests that if the Rochelongue site was indeed a shipwreck (or a deposit event), it most likely occurred around the late 7th or early 6th century B.C.

What was found at the Rochelongue site?

The material assemblage recovered from the Rochelongue underwater site consisted primarily of metallic objects. These can be categorised as follows:

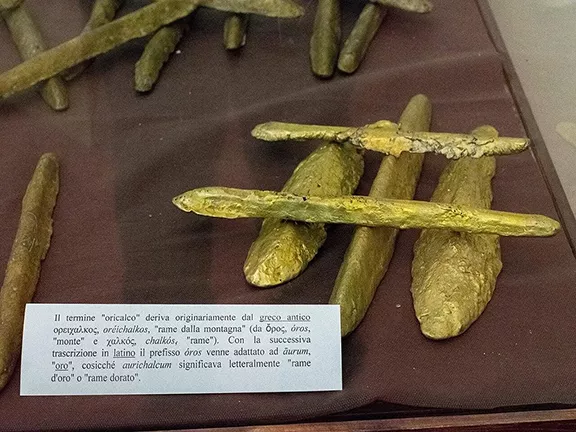

Raw or semi-processed materials: This included galena (lead ore), plano-convex copper ingots, tin and lead plaques, and slag. The Rochelongue site is significant due to its large number of copper ingots, including 119 complete ingots, 239 partial ingots, and 2,961 fragments of smelted copper. Some of these copper ingots bear a 'Y' stamp or anthropomorphous symbols similar to examples found in Greece.

Manufacturing wastes: This category includes unsuccessful mould castings.

Manufactured objects: This diverse collection includes bracelets, rings, pendants, fibulae or pins, swords, arrow points, spear fragments, a 'Fleury' type belt buckle and axe heads.

The total weight of the assemblage amounts to approximately 1.3 tons.

Where did the Rochelongue artefacts come from?

The sources indicate that the material assemblage from the Rochelongue underwater site includes items of diverse cultural origins. These origins point to a variety of connections, reflecting the coastal mobility and cross-cultural interactions in the region during the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age transition.

The origins of the Rochelongue assemblage can be summarised as follows:

Copper ingots: Some copper ingots bear a 'Y' stamp or anthropomorphous symbols similar to examples found in Greece. Similar markings have also been found on ingots from the Giglio shipwreck, which has been interpreted as both Etruscan and, and off the coast of Haifa, Israel. The 'Y' stamp ingots have been used to suggest an early Greek presence in West Languedoc.

The site also contained galena (lead ore), tin and lead plaques, and slag. The sources do not explicitly state the origin of these specific materials.

Manufactured objects: Some weapons are associated with the Atlantic bronze metalworking tradition. Others are presumably linked to the Iberian Peninsula.

Bracelets are clearly connected to central European cultural traditions and likely originated in eastern France.

Fibulae: The fibulae present a complex picture. Similar double-spring fibulae have been found in Phoenician contexts of the 7th and 6th centuries B.C.. Some believe the triangle-bow fibula originated in Cyprus between the 10th and 9th centuries B.C., although others argue for a local origin. Navicella-type fibulae are typical of northern Italy. The Rochelongue examples are dated from the second half of the 7th century to the first half of the 6th century B.C.

Manufactured goods such as pendants and pins have parallels from the orientalising sanctuaries of Sicily and from the Heraion of Perachora on the Corinthian Gulf.

The presence of these diverse items suggests that the Rochelongue site reflects a period of significant maritime connectivity and cross-cultural interaction in the western Mediterranean, involving local populations and contact with Etruscan, Greek, Phoenician, and other groups. The assemblage includes both native and foreign items, indicative of regional and long-distance maritime trade networks.

What was the purpose of the assemblage?

The purpose of the metallic assemblage found at the Rochelongue underwater site is not definitively established and remains a subject of ongoing debate. However, several potential purposes have been proposed:

Trade and Commercial Activity: If the site represents a shipwreck, as initially suggested by its discoverer Andre Bouscaras, the metallic objects would constitute its cargo intended for trade. The diverse nature of the assemblage, including raw materials like copper ingots and galena, semi-processed items, manufacturing waste, and finished goods such as weapons and ornaments, supports this possibility. The presence of items with potential Greek, Iberian, and central European origins suggests that the vessel, if it were a trading ship, was involved in a maritime exchange network within the western Mediterranean.

The variety of cultural origins points to the site being within a pre-colonial contact zone where goods from different regions were potentially being exchanged.

Ritual or Votive Deposit: Jean Gasco has argued that the site might represent a votive deposit. This interpretation is supported by the absence of definitive wooden hull remains or typical shipwreck equipment. The practice of offering metal hoards in aquatic environments was known in the European Bronze Age. In this context, the deposition of the metallic objects could have had a supplicatory or ritualistic purpose.

In further support of this argument, the Greeks established a settlement at Agde (Agathe Tyche) during the 6th century BC, soon after or contemporaneously with the depositions made at Rochelongue. Could the depositions be in the nature of an underwater shrine to bless a new settlement?

Blurred Distinction Between Ritual and Commercial Activity: Some scholars propose that in ancient coastal societies, the separation between ritual and habitual actions, including commercial dealings, might not have been strict. Therefore, the assemblage could represent goods intended for trade that were accompanied by or formed part of a ritual offering at a significant location like the convergence of land, riverine, and maritime routes.

Ultimately, while the exact purpose of the assemblage remains debated, the evidence strongly suggests a connection to either maritime trade and exchange in a pre-colonial contact zone or a form of ritual deposition, or potentially a combination of both.

Political situation at the time

The Rochelongue underwater site offers insights into the political situation of West Languedoc during the Late Bronze Age (LBA) to Early Iron Age (EIA) transition (roughly the 8th to 6th centuries B.C.) by highlighting the dynamics of coastal mobility, cultural contact, and emerging social complexities.

The region was undergoing socio-economic change influenced by increasing maritime interactions with Mediterranean cultures. Prior to the EIA, the traditional socio-economic model for west Languedoc was one of agro-pastoral subsistence with some coastal resource exploitation, characterised by dispersed settlements. However, the EIA witnessed the emergence of new social structures with greater social hierarchy and the appearance of 'big men'. This suggests a shift in the local political landscape, potentially driven by increased interaction and competition for resources or prestige.

The presence of the Rochelongue assemblage, with its mix of native and foreign metallic objects, points to active engagement of local populations in pre-colonial contact and trade networks. The site is seen as representative of a "contact zone", a space of sustained interaction between indigenous people and foreign cultures (Greeks, Etruscans, Phoenicians), where cultural differences were negotiated through economic and potentially political means. This indicates that local communities were not passive recipients of external influence but actively involved in the evolving political economy of the region.

The study of the Rochelongue site, according to Aragon Nunez, allows for a broader assessment of the local population in terms of maritime cultural contact and their capacity for coastal mobility. The distribution of the metallic objects suggests networks of connectivity were developing. This mobility and connectivity are vital for understanding the socio-economic changes and cultural encounters occurring in western Languedoc as Mediterranean cultures began to exert their influence. The site highlights the convergence of interests between foreign groups seeking mineral resources and local privileged groups desiring prestige goods, which could enhance and maintain their social distinction. This dynamic of exchange and the potential for local elites to benefit from it would have undoubtedly shaped the political relationships and power structures within the region.

Furthermore, the emergence of more stable settlements and necropoli in the Hérault basin during the 7th century B.C., such as Peyrou in Agde, indicates a degree of territorial stability and potentially the consolidation of local power. By the end of the EIA, the appearance of Oppida, permanent and sometimes fortified settlements, further testifies to the stability of some communities and their control of surrounding territory, reflecting a more defined political organisation. The Rochelongue site, dated to the end of the 7th or the first quarter of the 6th centuries B.C., falls within this period of significant transformation.

The Rochelongue site should also be considered alongside the 'Launacien' phenomenon', a local metallurgical tradition characterised by bronze hoards. Aragon Nunez suggests that these metal accumulations, including the Rochelongue assemblage, should be considered in the context of Mediterranean relations. Dominique Garcia views Launacien deposits as representing "an original economic phenomenon that consisted of the development of indigenous metallurgic production for exchange purposes". This indicates a level of local economic organisation and agency that would have had implications for the political landscape, as control over metal production and exchange would have been a source of power and influence.

In conclusion, the Rochelongue site, through its material assemblage and context, suggests a political situation in West Languedoc during the LBA-EIA transition characterised by:

Increasing social complexity and the emergence of local elites who benefited from new exchange networks.

Active participation of local populations in maritime contact and trade with various Mediterranean cultures, shaping pre-colonial dynamics.

The development of local economic systems, such as the 'Launacien' metallurgical production, which would have influenced power structures.

A move towards more stable settlements and territorial control by some communities by the end of the EIA.

The region acting as a "liminal zone" where local and foreign customs interacted, potentially leading to both cooperation and tension.

The Rochelongue site, therefore, provides a snapshot of a region undergoing significant political and socio-economic transformation driven by increased connectivity and interaction within the wider Mediterranean world.

Where can the Rochelongue deposits be seen?

Musse de l'Ephebe et d'archeologie sous-marine (Museum of the Ephebe and Underwater Archaeology)

References

E. Aragon Nunez, The Rochelongue underwater site and the coastal mobility in West Languedoc (France) during the transit from Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age, RIPARIA 6 (2020), 1-291 .

E. ARAGON, The Rochelongue Underwater site: (Re)assembling Contacts and Connectivity through a Multi-Methods Approach, A. CHO?UJ, M. MILESZCZYK, K. TRUSZ (eds.), ?twiatowit Supplement Series U: Underwater Archaeology, Vol. I., Warsaw 2018, 39-62

J. GASCO, Geographie regionale de l'age du bronze en Languedoc, Quaderns de prehistoria i arqueologia de Castell 29, 2011, 135-151.

J. GASCO, La ceramique des cultures de l'extreme fin de l'age du Bronze en Languedoc occidental, Documents d'archeologie meridionale. Protohistoire du Sud de la France 35, 2012, 127-150.

B. DEVILLERS, G. BONY, J.-P. DEGEAI, J. GASCO, T. LACHENAL, H. BRUNETON, F. YUNG, H. OUESLATI, A. THIERRY, Holocene coastal environmental changes and human occupation of the lower Hérault River, southern France. Quaternary Science Reviews 222/1, 2019.

J. GUILAINE, L. CAROZZA, D. GARCIA, J. GASCO, T. JANIN, B. MILLE, Launac et le Launacien. Depots de bronzes protohistoriques du sud de la Gaule, Presses Universitaires de la Mediterranae, Montpellier 2017.

P.A. MOYAT, DUMONT, J.-F. MARIOTTI, T. JANIN, S. GRECK, L. BOUBY, P. PONEL, P. VERDIN, S. VERGER, D'couverte d'un habitat et d'un de pot metallique non funaraire du VIIIe s. av. J.-C. dans le lit de l'Herault d' Agde, sur le site de La Motte, Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 54/1, 2010, 53-84.

D. GARCIA, Entre Ibires et Ligures: Lod'vois et moyenne vallee de l'Herault protohistoriques, CNRS editions, Paris 1993.

D. GARCIA, pave de Rochelongue (Cap d'Agde), LUC LONG, PATRICE POMEY, J.-C. SOURISSEAU (eds), Les etrusques en mer: 'paves d'Antibes ' Marseille, edisud, Marseille 2002, 41.

D. GARCIA, La Celtique mediterranienne: Habitats et socictus en Languedoc et en Provence du VIIIe au IIe siecle avant JC., Editions Errance, Paris 2004.

D. GARCIA, J. VITAL, Dynamiques culturelles de l'age du Bronze et de l'age du Fer dans le sud-est de la Gaule. Celtes et Gaulois, L'Archeologie face l'Histoire 2, 2006, 63-80.

Sourisseau J.C., Garcia D. 2010 Les Echanges sur le Littoral de la Gaule Meridionale au Premier age du Fer du Concept d'Hellenisation celui de Mediterranisation, 'Archeologie des Rivages Mediterranaens' 50, 237 - 246.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC 2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC

2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC 3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC

3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC 4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC

4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC 5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC

5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC 6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC

6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC 7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC

7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC 8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period

8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period 9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period

9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period 10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC

10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC 12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC

12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC 13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC

13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC 14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC

14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC 15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC

15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC 16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC

16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC