Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

The Giglio Shipwreck: A 6th Century BC Etruscan Merchant Vessel

Discover the fascinating Giglio Shipwreck, a 6th-century BC Etruscan merchant vessel found off the coast of the island of Giglio, Italy. Learn about its construction, cargo, and the insights it provides into Etruscan trade and maritime technology.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-01-6 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 3,184 times

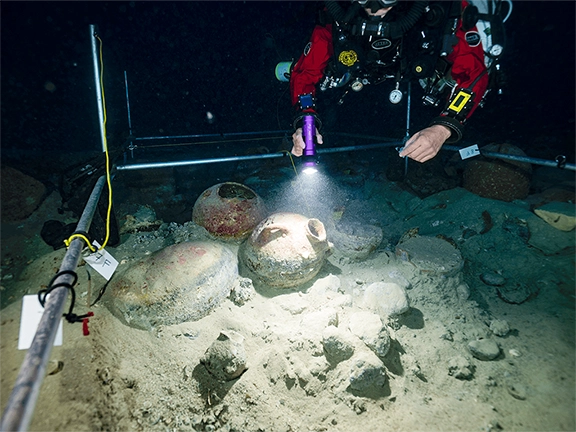

Collection of similar amphorae - Marsalla, Sicily

Where was the Giglio shipwreck found?

The Giglio wreck was found at a depth of 45 - 50 metres, on the seaward or western side, of a reef in Campese Bay which is on the western side of the island of Giglio.

The island of Giglio lies 50 kilometres south of Elba and 15 kilometres from the mainland at the southern end of the Tuscan Archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Who excavated the Giglio shipwreck?

Column Krater - 6th century BC - Agrigento, Sicily

The Giglio wreck site was discovered in 1961 by a British diver called Reg Vallintine. The site remained unexcavated, except by looters, until 1982 when Mensun Bound, an underwater archaeologist from Oxford University 'rediscovered' the wreck, assisted by Vallintine. Excavations began that year and were conducted annually until 1986.

When did the Giglio wreck sink?

The Giglio wreck sank about 580 BC

How was the Giglio ship built and what were its dimensions?

Only a part of the Giglio wreck has been recovered, the after end of the keel and some planking. Nine different species of wood have been identified as being used in the construction of the ship; pine, fir, box, oak, holm oak, elm, olive, hazel, and Phillyrea.

The ship was constructed shell first and laced. The style of lacing is unusual, having been identified on only two other ancient shipwrecks, the Bon Porte ship about 550 BC and the Gela ship that sank about 500 BC.

This lacing technique used on these three ships involves the following steps:

Notching: Cut triangular notches along the inner edges of the planks.

Drilling: Drill diagonally through each plank, starting from the notch. Instead of exiting the plank on the outer side, the hole should emerge at the seam where the planks meet.

Lacing: A matching notch and drill hole are created on the adjacent plank. Cord is threaded back and forth through the matching holes in the two planks. The cord is pulled tight to secure the planks together. Each hole is then plugged with a small wooden dowel.

Reinforcement: Wooden pins (treenails) are inserted horizontally across the seams to provide extra strength and support.

Waterproofing: Pine pitch (resin) is used to seal the seams and prevent water leakage.

What was the cargo on the Giglio shipwreck?

Etruscan aryballos

The Giglio ship was carrying a mixed cargo of ceramics, metallic objects and personal possessions.

Ceramics: About 28 pots, two almost complete, the rest in fragments, have been identified as Aryballoi. Aryballoi are small, spherical, jars that would have contained unguents and perfumes. Four distinct types of aryballoi are represented, Corinthian, Etruscan, Laconian and Ionian. The type reflects their source, Corinth in south and central Greece, Etruria in northwest Italy, Laconia in southern Greece, and Ionia on the western coast of Turkey. The designs, including some from the 'Warrior' group indicate they were manufactured between 620 and 570 BC.

Similar oinochoai from Mozia, Sicily

The ship also carried oinochoai, jugs used to serve wine, and kothon, similarly designed to serve wine but designed to prevent spillage. Both with a Corinthian design.

Other Ionian ware included bowls and jugs.

Four designs of amphorae were recovered from the wreck, Phoenician or Punic, eastern Greek, Samian (from the north Aegean islands), and, most prolific, Etruscan. From the residues and spillage, the Etruscan amphorae were carrying olives and pitch. The pitch carrying amphorae were themselves lined with pitch, indicating they were recycled, having originally carried another product. The Samian amphorae were small capacity jars that probably transported olive oil, for which Samos was famous in ancient times.

Corinthian helmet - same age - Malaga museum

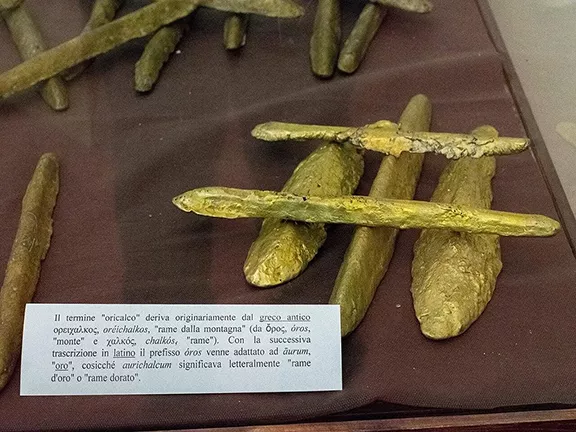

Metallic objects: The Giglio ship was carrying a mixed bag of metallic objects including weaponry, lead and copper ingots, copper nuggets, fishing weights, and iron bars that could have been spits.

Notable amongst the weapons were two Corinthian bronze helmets. One was of a basic design and poorly manufactured but the second was elaborately decorated. Wild boars charge down the cheek-pieces, while open-mouthed snakes run across the brows and curl upwards at the temples. This helmet was looted by a German diver and sold to a private collector in Hamburg who deposited it in a bank for safe keeping. The collector has no plans to return the helmet to Italy.

Over thirty arrowheads of varying design, but all cast in moulds, were scattered amongst the other cargo.

The wreck gave up four copper 'bun' ingots and nine lead ingots. Many more have likely been carried off by looters (appropriately called clandestine in Italian), over the years.

135 fishing weights were also recovered. These were variously designed to be used on lines, draw nets and casting nets.

Greek/Spartan auloi, same period

Miscellaneous cargo: A wooden writing tablet, part of a diptych, was discovered amongst the cargo along with a carved leg from a couch. More interesting was a boxwood lid with ivory studs and an intricate, turned, drilled and hand carved decoration.

A fascinating find was that of a set of nine or ten auloi, or musical pipes. One was found intact along with fragments of the remainder. The intact pipe and some of the fragments had no holes, whilst the others each had five finger holes on their upper parts with a single hole on the underside at the mouth end. Each pipe differed in length, bore, and placement of the finger holes so produced different notes. All, apart from one, were made of boxwood, the exception was made of ivory. Vase paintings of the period show musicians playing two pipes simultaneously in their mouths.

Finally, the divers recovered two pieces of raw amber that had become trapped in pitch that had escaped from one of the amphorae. It is likely that more amber had floated away from the wreck.

What was the purpose of the cargo?

Crater - same period - Mozia, Sicily

The range of designs and form of the aryballos, ionochai, kothon, bowls, and jugs, would point towards a consignment of domestic crockery for trading purposes.

The arrowheads and helmets could have been part of the ship's manifest, perhaps used by members of the crew to defend their ship and cargo from the pirates that infested the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The copper and lead ingots would be part of the mixed cargo destined for a metal workshop. The Etruscans were master bronzesmiths who exported their finished products all over the Mediterranean.

The items labelled 'miscellaneous cargo' were likely all personal belongings apart from the Baltic amber that had been an exotic and sought after trade commodity since the 16th century BC. The amber would have arrived at Etruria overland via the infamous Amber Road.

Where did the ship come from and where was it going?

From the details of its construction and the diverse sources of its cargo, it is likely that the Giglio ship was an Etruscan ship, engaged in trade between Sicily, probably the Greek emporium of Himera (where all the Greek sourced products would have been available), and Etruria (only 15 kilometres east of Giglio).

Why did the Giglio ship sink?

A debris trail led from the reef below which the Giglio was found, in a straight line down the seaward side of the reef to the seabed proper. The Giglio ship apparently foundered on the reef, perhaps driven there by strong westerly winds. The sharp coral would have ripped the bottom from the ship. A portion of the keel was discovered at the end of the debris trail.

Political situation at the time

The Etruscan civilization flourished in central Italy from the 8th to the 3rd century BC. Its prosperity was largely based on trade, both within Etruria and with other Mediterranean civilizations. The Etruscans were especially known for their production and export of iron, but they also traded other goods such as pottery, wine, and olive oil. In exchange, they received ivory from Egypt, amber from the Baltic, and pottery from Greece and Ionia.

By the 6th century BC, Etruscans were exporting a wide range of goods, including grain, pine nuts, olive oil, wine, stone sculpture, bronze cauldrons, marble, wood, goldwork, pottery, horse bits, and inlaid ivory plaques. Etruscan artisans produced high-quality goods that were in high demand throughout the Mediterranean world.

By the 6th century BC, the Tyrrhenian Sea was firmly within the Greek area of influence, however that situation was not to last. The Etruscans were great mariners, and, in 540 BC, a combined fleet of Etruscan and Carthaginian ships defeated the Greeks, thus ensuring Etruscan overseas trade.

Ongoing Research

Further research is needed to determine the origin of the copper and lead to illustrate the wide-ranging nature of the Mediterranean trading networks that developed during the iron age.

Where is the Giglio wreck and its cargo now?

The entire top floor of the national underwater museum at Porto Santo Stefano is dedicated to the finds from the Giglio ship. The museum is in the Fortezza Spagnola that is temporarily closed (December 2024). Check before you go.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC 2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC

2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC 3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC

3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC 4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC

4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC 5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC

5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC 6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC

6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC 7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC

7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC 8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period

8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period 9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period

9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period 10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC

10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC 11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC

11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC 13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC

13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC 14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC

14: Ispica - Greek Shipwreck 600 - 400 BC 15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC

15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC 16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC

16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC