Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

Ispica a 6th Century BC Greek Shipwreck found off Sicily

A 2,500-year-old Greek shipwreck, dating to between the 6th and 5th century BC, discovered off Sicily's Santa Maria del Focallo reveals rare artifacts and insights into ancient Mediterranean trade.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-07-19 | Last Updated 2025-07-19 | Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

This article has been visited 2,061 times

Diving on Ispica

6th Century BC Shipwreck Discovered off the Shores of Sicily

Off the coast of Santa Maria del Focallo, in Sicily's Ispica region, on the southernmost tip of Sicily, archaeologists have brought to light a discovery that promises to rewrite or at least further illuminate, chapters of ancient maritime history. Buried beneath layers of sand and rock, the remarkably well-preserved remains of a Greek ship, dating to between 600 and 400 BC, offers a rare glimpse into a little known but crucial era of Mediterranean trade and seafaring. This 2,500-year-old vessel is not merely an old wreck; it is a time capsule, revealing secrets of a world long past.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

A Volunteer's Crucial Role

The story of this extraordinary find began in 2022, not with a professional expedition, but with the keen eye of a volunteer diver, Antonino Giunta. While exploring the shallow waters, Giunta noticed "curious piles of stones and bits of wood", subtle clues hinting at something significant hidden below. His prompt report to the Soprintendenza del Mare, Sicily's Superintendency of the Sea, set in motion a full-scale archaeological investigation.

Unearthing the Ispica

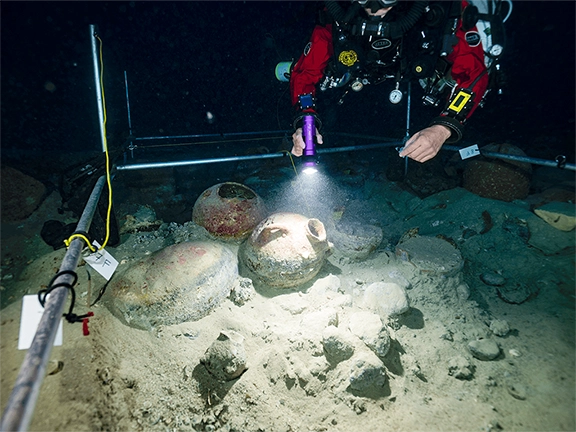

Underwater archaeologists from the University of Udine, collaborating with the Soprintendenza del Mare, embarked on a three-week excavation in September 2024, followed by a second five-week campaign between May and June 2025. They found the ship resting just six metres deep, its wooden hull surprisingly intact despite over two thousand years underwater. This exceptional preservation, however, comes with its own challenges. Professor Massimo Capulli, who leads the research programme at the University of Udine, noted the hull's "extremely delicate" condition due to centuries of mollusc activity, emphasizing that working with such fragile remains "requires not only expertise, but also a lot of caution".

Ancient Naval Architecture and Rare Finds

The vessel itself reveals much about ancient shipbuilding. Its hull was constructed using the "on-the-shell" or "su guscio" technique. This method involved tightly joining planks with dovetail or mortise and tenon joints to form a self-supporting structure before adding internal framing.

This sophisticated early engineering provides invaluable insights into the nautical skills of the era. Among the most astonishing discoveries from the 2025 campaign were a mast—a component rarely found preserved in ancient shipwrecks—and a section of rope in excellent condition. "With a careful approach, we managed to document new and significant parts of the wreck, such as the mast—which is extremely rare to find preserved," Professor Capulli remarked.

While some reports also mention the discovery of a "ship's wheel" alongside the keelson, it is important to clarify that ancient Greek ships did not use steering wheels as we know them today. Steering wheels became common only in the 18th century AD. Ancient vessels relied on large steering oars, or quarter-rudders, mounted on the stern. The "wheel" found likely refers to another circular component of the ship's internal structure, its precise function still under investigation.

Artifacts from the Ispica wreck

Apart from the ship's structure, archaeologists unearthed a trove of artifacts. They found black-figure Greek pottery, typically produced between the 7th and 5th centuries BC, and a small alabastron, a perfume vessel, uniquely inscribed with the Greek word "Ναῦ" (Nau), meaning "ship". This personal touch offers a rare, direct link to the people who sailed this ancient vessel. The site also yielded numerous amphorae, ancient containers typically used for transporting goods like wine, oil, or grains. While the specific contents of these amphorae from this wreck are still being analysed, such finds are crucial for understanding the economic life of the period.

Anchors Across Millennia

Credit: Soprintendenza del Mare

Perhaps most intriguing is the collection of six anchors found near the wreck. Four of these are prehistoric stone anchors, suggesting the area's long history as a maritime hub. The other two are inverted "T"-shaped iron anchors, dating to the much later 7th century AD, from the Byzantine period. This "complex layering of finds" indicates that the Santa Maria del Focallo area served as a consistently used "landing or shipping point for centuries".

Sicily: A Crossroads of Ancient Civilizations

During the 6th and 5th centuries BC, Sicily was an often-contested focal point of extensive Greek colonization, determined to establish a significant presence in what became known as Magna Graecia. The Santa Maria del Focallo shipwreck dates to a "crucial period for the transition between archaic and classical Greece". This was an era where the Greek colonies in Sicily played a major, strategic role in the wider Mediterranean, shaping cultural, political, and economic landscapes.

This period saw a fierce, often violent, competition for control of lucrative trade routes and resource-rich territories among three formidable maritime powers: the Etruscans, the Greeks, and the Carthaginians.

The Etruscans, based in central Italy, built their wealth on abundant metal resources, particularly iron from Elba, and exported agricultural goods like grain, olive oil, and wine, alongside their distinctive bucchero pottery across the Mediterranean. Their trade network, though decentralized among independent city-states, reached as far as Egypt, the Baltic, and even inland Europe via Massalia.

Meanwhile, Greek colonization exploded across the Mediterranean. By 500 BC, Greeks had established some 500 colonies, accounting for an astonishing 40% of all Hellenes in the ancient world. They strategically founded settlements like Syracuse and Gela in Sicily, transforming southern Italy and Sicily into "Magna Graecia" or "Greater Greece." These colonies served as vital trade centres, exporting fine pottery, wine, and olive oil, while importing essential raw materials such as timber and metals. This aggressive expansion, driven by economic opportunity, inevitably brought them into direct conflict with established powers.

Carthage, a powerful Phoenician offshoot in North Africa, emerged as the dominant maritime force in the western Mediterranean during the 6th century BC, controlling vast territories from Tripolitania to southern Spain, including western Sicily and Sardinia. Their strategic location and superior harbour allowed them to fiercely guard a lucrative trade monopoly, extending even to the Trans-Saharan routes that brought gold, ivory, and slaves from tropical Africa. Carthaginian merchants exported manufactured goods and salt fish, reaching markets as distant as Corinth in Greece, the Levant and Egypt. Unlike the more decentralized Greek or Etruscan trade, Carthage's commerce was a centrally managed and strategically enforced component of its state power, making them a formidable and often aggressive competitor.

These overlapping interests and ambitions frequently escalated into open conflict. Recognizing the growing Greek threat, Carthage forged an anti-Greek alliance with the Etruscans, who at the time held significant influence over Rome. This alliance directly countered the westward push of Greek colonies like Massalia. Conflict was inevitable and the two forces met at the Battle of Alalia, fought around 540-535 BC off Corsica. Here, a combined Etruscan and Carthaginian fleet of 120 ships clashed with 60 Greek Phocaean vessels. Though the Greeks achieved a tactical victory, driving off the allied fleet, they suffered devastating losses, with nearly two-thirds of their ships destroyed. The historian Herodotus famously called it a "Pyrrhic victory."

This costly engagement forced the Greeks to abandon Corsica, which then fell under Etruscan control, while Carthage solidified its hold on Sardinia and parts of southern Spain. Such conflicts, including earlier clashes like the one near Lilybaeum in Sicily in 580 BC where Phoenician cities allied to defeat Greek forces, underscore the pervasive nature of this ancient competition, where economic rivalries constantly reshaped the balance of power across the Mediterranean.

Sicily remained a consistent battleground. For centuries, Greeks and Carthaginians fought intermittently for control of the island's territory and the allegiance of its indigenous populations. While the 6th century BC saw these rivalries simmer, the stage was set for larger conflicts, such as the Battle of Himera in 480 BC, where a great Carthaginian army suffered a significant defeat at the hands of the western Greeks. Interestingly, this battle was allegedly fought on the same day as the naval Battle of Salamis between Greek city states and Persia.

The comprehensive study of the Santa Maria del Focallo shipwreck will thus contribute substantially to a more granular understanding of the broader economic and political landscape of the Archaic and Classical Mediterranean. It illustrates how maritime commerce functioned and adapted amidst significant political and military tensions, offering insights into the resilience and strategies of ancient seafaring communities in a contested region long before Rome's rise to dominance.

Francesco Paolo Scarpinato, Sicily's regional councillor for cultural heritage, aptly described the discovery as an "extraordinary contribution to the knowledge of the maritime history of Sicily and the Mediterranean". He added that the wreck is a "precious piece of the submerged Sicilian cultural heritage," highlighting the island's central role in ancient traffic and cultural exchanges.

The Kaukana Project: Searching for Sicily’s Submerged Heritage

The ongoing investigation is part of the ambitious "Kaukana Project," a long-term scientific initiative launched in 2017. Led by the University of Udine in collaboration with the Soprintendenza del Mare, the project aims to reconstruct the coastal and submerged landscape of Sicily's Ragusa province. Researchers employ innovative techniques like underwater photogrammetry to create detailed 3D models of the wreck, ensuring meticulous documentation of these fragile remains. They also collect samples for paleobotanical analysis, hoping to identify the ship's construction materials and understand the ancient environment.

The project even extends to public engagement, with the University of Udine collaborating with Martin Scorsese's Sikelia Productions on a docufilm titled "Shipwreck of Sicily," which includes footage from the Ispica excavation.

A Legacy from the Deep

The Santa Maria del Focallo, Ispica, shipwreck is far more than a collection of ancient timbers and artifacts; it is a historical archive submerged in the Sicilian waters. Its continued study promises to unlock further secrets of ancient seafaring, trade, and the intricate relationships between the civilizations that shaped the Mediterranean world, reinforcing the critical importance of sustained archaeological research and conservation efforts in this historically rich region.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC

1: Dor's Iron Age wrecks 11th-6th centures BC 2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC

2: Carmel Atlit shipwreck c 800 - 750 BC 3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC

3: Tanit and Elissa c 750 BC 4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC

4: Xlendi Bay shipwreck off Gozo c 700 BC 5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC

5: The Kekova Adası shipwreck c 650 BC 6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC

6: Kepçe Burnu Shipwreck 650 – 600 BC 7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC

7: Çaycağız Koyu Shipwreck c 600 BC 8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period

8: Mazarron II 625 - 570 BC Phoenician period 9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period

9: Mazarron I c 600 BC Phoenician period 10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC

10: The Bajo de la Campana c 600 BC 11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC

11: The Rochelongue underwater site c 600 BC 12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC

12: Giglio Etruscan shipwreck c 580 BC 13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC

13: Pabuç Burnu shipwreck 570 - 560 BC 15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC

15: Gela I shipwreck 500 - 480 BC 16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC

16: Gela 2 shipwreck 490 – 450 BC