Levantine Cave Art

Levantine Cave Art during the Magdalenian

The Magdalenian hunter gatherer developed a distinctive art form that included meticulously recorded anatomy, representations of motion, elements of realism and explored the mystical links between abstract signs and animals.

By Nick Nutter on 2024-02-16 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Levantine Cave Art

This article has been visited 2,863 times

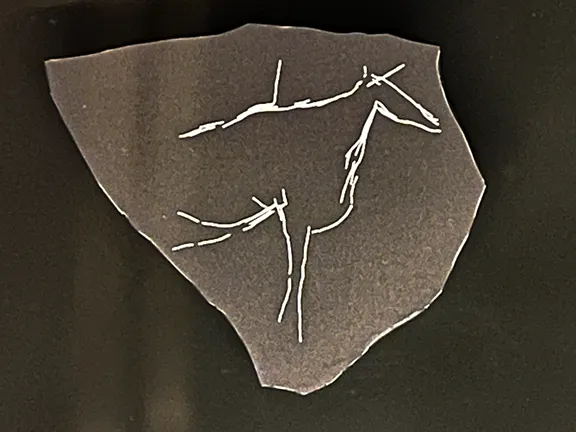

Anatomy study circa 15000 BC

First Images of Anatomy

The Magdalenian style is highly representative. In this example, notice the meticulously drawn elbows, knees, hooves and tail of an animal. Unfortunately, the plaque is not complete. Even so it is a most lifelike impression.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Anatomy of Aurochs

Anatomy of an Aurochs circa 15000 BC

Nobody could doubt that the artist was making an engraving of an aurochs. This is one of the most realistic plaques in the collection.

Barbed Wire Strokes

Barbed Wire Style circa 14000 BC

Another typically Magdalenian feature is the so called 'barbed wire' strokes, seen here to illustrate a goat. Interestingly, this same approach can also be seen in cave art from the same period from Portugal and the French Pyrenees.

During this period we also see attempts to portray motion by drawing the same image multiple times, superimposing and offsetting one on top of another.

This technique is used to this day by cartoonists who produce many images, each one showing a slight advance of the desired movement and then 'stack' the images and rapidly flick through them to see the overall movement.

Importance of the Horse

Horse in Profile

During the Magdalenian period, artists began to portray equine figures differently to anything seen before. The animal was presented in profile and in proportion. Extra attention was given to the shape of the head, notice the ear in this profile view.

Symbolistic Animal Representations

Metamorphosis between Life and Death circa 14000 BC

This plaquette displays some of the elements that may help us understand the symbolistic nature of animal representations, the link between a bodily presence and abstract signs. Here two bovine heads are shown in elongated form, connected to bands of curved lines with a zig zag pattern between. It is tempting to think that the artist is trying to portray the metamorphosis between the everyday and spiritual planes, a life for the animal after its death.

The Wild Boar

Wild Boar circa 13000 BC

There are only a handful of representations of wild boar in Palaeolithic art which is why this example is so valuable.

Partridge or Heron?

Partridge or Heron circa 13000 BC

Images of birds are similarly rare and only start to appear when, towards the end of the Palaeolithic period, hunter gatherers developed the techniques to net small birds. It is thought that this image represents a partridge although I think it looks more like a heron. Either way, as fine a meal then as they are today.

Complex Drawings

Complex Images circa 12000 BC

Towards the end of the Magdalenian period, artists produced complex drawings. We can appreciate the workmanship and time that went into these designs, but we shall never know what they were trying to represent, imaginary animals, complex signs, who knows?

The Serpentine

Serpentiform circa 12000 BC

The serpentiform seems to be common to specific areas and may represent a river boundary or another landscape feature. It may also identify a particular population group, again we shall probably never know.

Why Parpallo Cave?

Another profile of a horse

I suppose the big question is, "Why did about eight hundred generations of hunter gatherers deposit their personal tokens and emblems in Parpallo cave?" Nobody knows for sure but Parpallo cave was used annually as a seasonal home by hunter gatherers throughout the Palaeolithic period. The cave is on a south facing slope of the Monduver Range, near Gandia, in Valencia province, 450m above sea level and a few kilometres away from the current coastline. This small cave has three chambers and a narrow vertical entrance facing south. The main chamber is the largest, 5 by 6m, and the other two are somewhat smaller.

It could be that the cave, and the hunts that would be launched from the cave, was considered so important, or perhaps a favoured place, that it became a shrine

Museum of Prehistory Valencia, Spain

The original limestone portable art plaques can be seen in a display at the Museo de Prehistoria de Valencia.

Rather than have the observer try to decipher barely discernible outlines on small pieces of limestone, modern spectroscopic means have been used to bring out the individual designs in great detail. Those designs have been reproduced in white on slate and the results are now displayed in chronological order.

I would like to thank the staff at the Museum of Prehistory in Valencia for constructing such an informative and detailed display and allowing Julie and myself to spend some hours photographing the plaques.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Levantine Cave Art - Gravettian to Solutrean

1: Levantine Cave Art - Gravettian to Solutrean