Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

Naval Technology in the Mediterranean during the Roman Era

Naval technology was spurred on during the Roman era by successive conflicts starting with the Punic Wars. Cargo ships continued to be built using a combination of locally inspired techniques influenced by major innovations by the Greeks and Romans. Warships saw a shift from large, ram-focused galleys like the quinquereme to a greater diversity of vessel types, including smaller and more agile ships.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-05-14 | Last Updated 2025-05-14 | Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 40,662 times

Naval Warfare Iron Age Style

Endurance of the Hellenistic Type (Roman Empire and Byzantine Period)

We saw in the previous article how the Hellenistic type of ship evolved.

While eventually replaced by a new type with a flatter bottom without a prominent keel and internal framing more strongly connected to the keel during the Roman Empire period, the Hellenistic system endured in the Eastern Mediterranean until at least the Early Byzantine period.

While the Hellenistic type offered good sailing qualities, it also revealed a structural weakness at the keel level. This weakness was attributed to the prominence of the keel, characteristic of the wine-glass cross-section, and the lack of connection between the keel and the floor timbers. Later wrecks found off the French coast, in particular the Pointe de Pomègues, Plane I, Caveaux I, Baie de Briande, and Chrétienne A showed evidence of losing their keels after experiencing a sudden shock.

This flaw was recognised, and attempts were made to eliminate it as we shall see when we look at the Madrague de Giens shipwreck (75 – 60 BC).

It is important to note that other architectural approaches continued to be used throughout this period, reflecting regional and local traditions, alongside the dominant Hellenistic system. Alongside the development of the Western Roman Imperial type of ship, we will look at regional developments of ancient shipbuilding such as the Romano-Illyrian tradition in the Adriatic, and the Northwestern Mediterranean Roman type.

Marsala shipwreck (c 250 BC) Sicily

The Marsala shipwreck is identified as the wreck of a Punic warship located near Marsala at the extreme western edge of Sicily. It is dated to the mid-third century BC.

This wreck is significant because it has all the main features of the Hellenistic architectural type. This architectural system is characterised by a tripartite structure of keel, planking, and framing, and includes features like a wine-glass cross-section, a rabbeted keel, carvel planking assembled by mortise-and-tenon joints, and a framing system of alternating floor timbers and half frames nailed to the planking. The Marsala wreck reflects the unification of architectural systems across the Mediterranean, from the Greco-Roman world to the Punic world, under this Hellenistic type.

Regarding its construction process, the Marsala wreck was entirely conceived and realized using a ‘shell first’ method. This means the hull was built from the outside inwards, with the planking forming the primary structure before the frames were added.

Furthermore, the hull of the Marsala wreck had lead sheathing documented. This sheathing served to strengthen and waterproof the hull.

Albenga (100 – 90 BC) Liguria, Italy

The Albenga was a large ship, estimated to be around 40 metres long and 10-12 metres wide, making it one of the largest Roman transport ships found in the Mediterranean. Its cargo capacity is estimated at 400-500 tons.

The wreck site is located about one mile off the coast of Albenga at a depth of approximately 42 meters.

The ship's primary cargo consisted of over 10,000 amphorae, mainly of the Dressel 1B type. These amphorae were primarily used for transporting wine from the Campania region of Italy, destined for markets in southern France and Spain. Evidence suggests that some amphorae may have also contained other goods.

Besides the vast quantity of amphorae, archaeologists have also recovered black-painted pottery, other types of ceramics, and personal items belonging to the crew and a possible armed escort, including seven bronze helmets of different styles.

The shipwreck is dated to between 100 and 90 BC, a period coinciding with the Romanization of the Ligurian region.

The ship was built with an oak frame and soft wood planking that was sheathed in lead. Interestingly, the main mast was found still in its original position, square below the main beam and circular above.

Cavaliere (c. 100 BC) Southern France

The Cavaliere shipwreck lies in 43 metres of water in the cove of Cavaliere, Le Lavandou, France, midway between Toulon and St. Tropez. It was excavated between 1974 and 1977.

The wreck is dated to about 100 BC. This dating is based on the assemblage of finds, including coins from Numidia, Spain, and Marseilles, along with the cargo that included amphoras, various ceramics, and quarters of pork. Coins from Numidia, Spain, and Marseilles were also found.

The Cavaliere is interpreted as a small coastal cargo vessel. The cargo suggests it was "tramping all around the western Mediterranean". Its size, contents, and construction features are consistent with other vessels from the Hellenistic/Republican period that were used for coastal trade.

The preserved remains are 13m long and 3m wide. These remains were "well preserved".

The recorded remains include a keel with the base of the endposts, the sternpost (which was doubled by a skeg), about 20 hull planking strakes, about 40 frames, and a mast-step timber.

Construction of the Cavaliere: The hull planking strakes were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints.

The frames, which consisted of alternating floor-timbers and half-timbers, were joined to the planking using internal lashings.

The pattern of ligatures (lashings) is not always regular on the Cavaliere wreck, similar to Mèdes 6 and Barthélemy B.

A waterproofing coating covered the joints, which affected the observation of the lashing system.

In summary, the Cavaliere shipwreck is a well-preserved example of a coastal trading vessel from the late 2nd/early 1st century BC, found off the French coast. Its construction features, notably the planking assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints and frames attached by internal lashings (though not always regularly applied), align it with other Mediterranean vessels from the Hellenistic/Republican period. The presence of coins and cargo from various locations in the western Mediterranean suggests a trading route involving multiple coastal settlements and ports.

Madrague de Giens (75 – 60 BC) Southern France

The Madrague de Giens shipwreck provides a detailed illustration of the Hellenistic architectural type at a high degree of sophistication. This open sea cargo ship was found at around 18 to 20 metres depth off the coast of the small fishing port of La Madrague de Giens on the Giens Peninsula, east of Toulon, on the southern Mediterranean coast of France.

The wreck is dated to the first century BC, around 75–60 BC. It is considered one of the best examples of the Hellenistic architectural type.

Dimensions and Tonnage: The ship was large for its time, measuring nearly 40m long, 9m wide, and 4.50m deep. Its tonnage is estimated to be 400 tonnes deadweight. This size places it in the category of myriophoroi, which generally carried 10,000 amphorae or 500 tonnes of deadweight in common use.

Architectural Type: Its structure is characteristic of the Hellenistic type. This system is based on a tripartite structure of axial frame, planking, and transverse framing. Everything indicates that the ship was conceived according to the principle of longitudinal and ‘shell’ construction.

Construction Method: Everything indicates that the ship was probably built using a ‘shell first’ method, where the planking was constructed before the framing was fully installed, consistent with the Hellenistic type principle.

Hull Structure: It features a hull cross-section with a wine-glass profile. The hull has double planking which is reinforced by lead sheathing. The keel is prominent.

Framing: The internal structure includes an internal axial frame. The framing system is characteristic of the Hellenistic type, composed of alternating floor timbers and half frames. Transverse beams are supported by the wales of the planking. Wales are longitudinal pieces applied to the exterior of the hull to provide extra strength and rigidity.

Stern Complex: This complex shows significant elaboration, including no fewer than six frame pieces buttressed together to provide rigidity to the long rake aft. It incorporates a stern heel, located under the sternpost and in extension of the keel, which functions like a drift spoiler.

Stem Complex: Located at the end of a long raised forefoot, the stem complex has an inverted (convex) stem. It is extended forward by a cutwater.

Drift Plan: The combination of the prominent keel, the drift spoiler (stern heel), and the cutwater forms a very important drift plan, contributing significantly to the ship's stability at all points of sailing.

Bolted Floor Timbers: A notable feature is that a number of floor timbers are attached to the keel by a strong copper bolt. This is presented as the oldest known archaeological example of this practice, although such bolts were described as used in the earlier Syracusia (that we looked at in the previous article, ‘Late Iron Age 700 – 264 BC). Despite being bolted, these floor timbers do not touch the keel and remain largely independent. The bolts appear to be a means of reinforcing the link between the keel and the floor timbers to address the inherent structural weakness of the longitudinal axis in this type, which is due to the prominent keel and the independence of the floor timbers. The presence of these bolts and their examination confirm they were not part of pre-erected frames and thus do not negate the ‘shell first’ construction principle.

Yassıada 2 (300 – 400 AD) Bodrum, Turkey

The Yassıada 2 shipwreck was discovered approximately 100 m south of Yassıada ('Flat Island') near Bodrum in southern Turkey at a depth of 38–42 m. It is dated to the 4th century AD.

The overall dimensions of the hull remains were 16 metres long by 5.2 metres wide. Its original length was estimated at 20 metres, and its beam at 8 metres.

The cross-section of the hull had a wine-glass-shaped bottom (described as 'à retour de galbord').

Construction Details of Yassıada 2

There was evidence of the remains of four wales. These wales were typically 160 mm wide and 160 mm thick. The wales were connected to components such as ceiling-planking and stringers.

An iron bolt connected one floor-timber and probably a keelson to the keel.

The hull was made watertight by internal and external coats of pitch.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Romano-Illyrian tradition

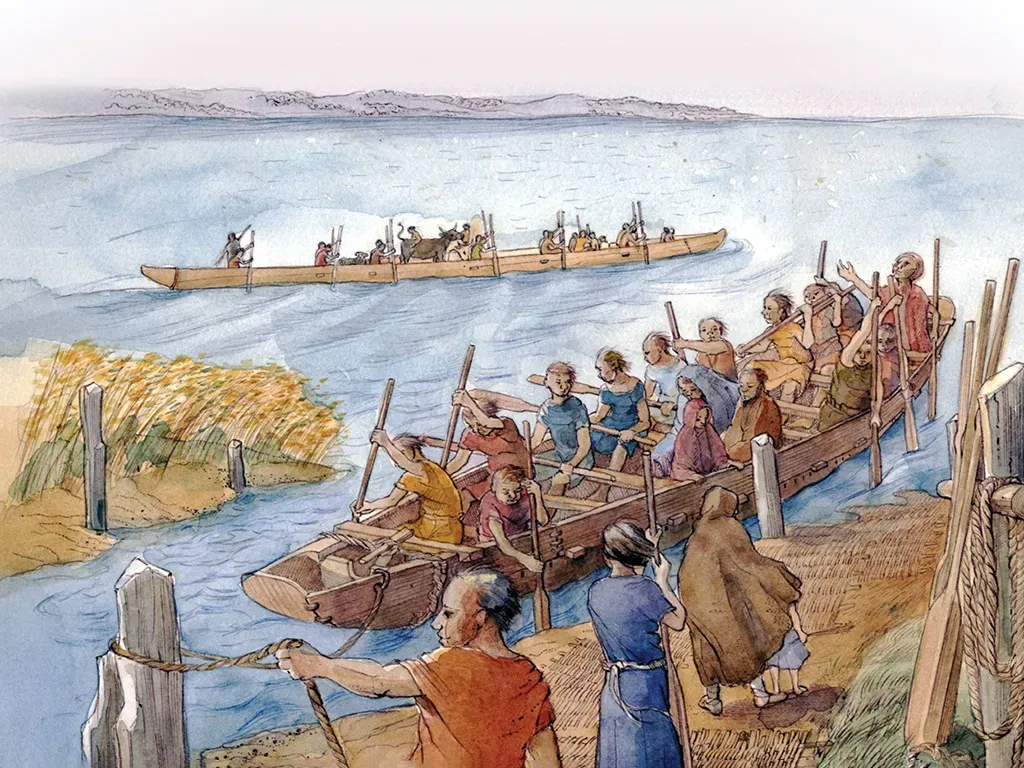

Illustration of a Laburna style ship

The Romano-Illyrian tradition is one of two distinct sewn-boat traditions identified in the Adriatic Sea that originated in the Early Iron Age between 1000 and 800 BC.

The first is the Indigenous Istro-Liburnian shipbuilding tradition discussed in the Early Iron Age Ships article.

Romano-Liburnian Shipbuilding Tradition

The second tradition is the Romano-Liburnian Shipbuilding Tradition, centred around the Liburna. This tradition emerged through the interaction and adaptation of Illyrian shipbuilding knowledge by the Romans. The Liburna warship, originally developed by the Liburnian people, became the hallmark of the Istro-Liburnian shipbuilding style during the Iron Age. Written sources from Greek and Roman authors, as well as iconographic evidence (like the Novilara Stele from the 6th/5th century BCE which depicts a battle between Liburnian and Picene vessels), highlight the characteristics and use of these ships.

The Liburna warship was a light and fast galley, designed for speed, manoeuvrability, and raiding. It evolved into a bireme design from a single bank of oars (like the Greek penteconter) to two banks of oars in the late Roman Republic. The ships were equipped with a rostrum for striking enemy vessels.

The Liburna's efficiency and effectiveness led to its widespread use throughout the Roman Empire and its name eventually became somewhat synonymous with smaller warships.

Adoption of the Liburna by the Romans (from the 1st century BC onwards): The speed and manoeuvrability of the Liburnian warship impressed the Romans, who adopted and adapted the design for their own navy by adding features like rams and potentially missile protection, making it a mainstay of their provincial fleets. This adoption occurred particularly in the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. The Liburna played a crucial role in Roman naval victories, such as the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

Evolution of the Liburna: Over time, the term "Liburna" became somewhat generic, used to describe various types of Roman warships, even cargo vessels, in late antiquity. However, its origins are firmly rooted in the shipbuilding traditions of the Istro-Liburnian people during the Iron Age.

There are six wrecks found to date that fall within this category, Zaton, Pula 1 and Pula 2, and Caskas 1,3, and 4. The first three are worth looking at in more detail.

Zaton (1 – 100 AD) Dalmatia

The site of Zaton, also known by the ancient name Aenona (today Nin), is located about 15 kilometres north of Zadar in Dalmatia, within the area defined as the north-eastern Adriatic or Istro-Liburnian sewn-boat tradition.

Archaeological research at Zaton has revealed multiple sewn-plank boats belonging to this tradition. Two were found in 1966 and 1982, dating to the 1st century AD. These findings re-evaluated previously excavated remains from the end of the 1960s. A third sewn wreck was discovered and partially uncovered in 2002–2003.

Regarding construction, the vessels found at Zaton are described as sewn-plank boats. The preserved parts of the two Roman-period boats are 6.50 metres and 8 metres in length, respectively. The third partially uncovered wreck is 5 metres in length. These ships exhibit similar characteristics to the Pula ships.

Pula 1 and 2 (100 – 250 AD) Istria

Identification and Dating: The Pula 1 and 2 wrecks are Roman vessels found in an urban rescue excavation within the ancient harbour basin of Pula, located in Istria. They are dated between the 1st century and the first half of the 3rd century AD based on stratigraphy and 14C AMS dates.

Planking Assembly (Sewing): Sewing techniques were an important part of their shipbuilding. Sewing is specifically used only for the planking seams. Channels for the sewing cord were cut into the planking, oriented more parallel than perpendicular to the plank edges. These channels reach the plank edges, and the plank edges themselves are chamfered so that the ligature does not protrude. Small pegs are used to lock the stitches in place. Fir laths holding a wadding made of a layer of vegetal fibres were placed over the seams prior to sewing. The wadding pad is similar in type to those observed in the contemporaneous Caska wrecks. Pula 1, which is described as a bigger sailing vessel than others in this group, presents a stronger sewing pattern of overedge stitches with a clamping turn (/I/I/I pattern). The type of cord used was a flat braid, similar to that seen on Pula 2 and Caska.

Watertightness: An internal coat of pitch ensured watertightness and was probably used on the external surface of the hull as well.

Framing: The frames of Pulas 1 and 2 are fastened to the planking using treenails. A few copper nails are also attested on Pula 2. The frames themselves have a rectangular section. Their base is crenellated to avoid damaging the sewn-plank seams, which is a characteristic shared with other vessels in this group. Limber holes are present in the frames.

Northwestern Mediterranean Roman Shipbuilding Tradition

Sewn Plank and frames details

The Northwestern Mediterranean Roman tradition is identified as a distinct shipbuilding tradition primarily characterised by a specific method of fastening frames to the planking.

The key feature of this tradition is the use of internal lashings to fasten the frames to the planking. This technique is associated with planking assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints. Sometimes treenails or nails were also used alongside internal lashings for frame attachment.

This tradition has been identified based on numerous shipwrecks found in the northern part of the western Mediterranean.

While some isolated instances of internal lashing are known from earlier periods and other contexts, the systematic use of this technique to fasten framing, forming a specific tradition, is seen during the Roman Period in the Northwestern Mediterranean. The earliest example is the La Tour-Fondue wreck, dated to the second half of the 3rd century BC by its cargo. However, the height of this tradition appears to be between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD. The wrecks are found in a Roman Northwestern Mediterranean area, along the coasts of Catalonia (NE Spain) and Provence (France).

The tradition encompasses different architectural types, including fluvio-maritime vessels (suited to lagoonal coasts and river deltas) and small coastal boats. Examples like Saintes-Maries 2 and Saintes-Maries 24 were relatively large, estimated at 15–18m and 20–25m long, with features like a wide, shallow keel plank and a flat bottom.

Origin and Nature of the Northwestern Mediterranean Roman Shipbuilding Tradition: The origin of this tradition is unclear. It appears to have been "grafted onto various previous architectural traditions" present in the region. Unlike other traditions (such as the Iberian with Punic influence or the Adriatic ones) that are strongly tied to a specific cultural context, the geographical extent and diversity of architectural types in the Northwestern Mediterranean tradition prevent identifying a specific cultural regional practice or shipyard fingerprints. While the boats were likely built locally according to wood supply and architectural type, some wrecks potentially originated elsewhere, like southern Italy or the Balkans. The modalities of its adoption still need to be clarified.

Relationship to Other Traditions: The Northwestern Mediterranean tradition is distinct from the Iberian tradition with Punic influence, despite both being in the western Mediterranean, notably in the method of frame fastening (external lashing on the planking vs. internal lashing/treenails/nails). The internal lashing technique itself appears to have ancient origins and was used sporadically in different contexts (like the Marsala Punic ship or the Greek Jules-Verne 9), but its systematic application to framing in this specific region during the Roman period defines the tradition.

In summary, the Northwestern Mediterranean tradition, is a technical shipbuilding tradition characterised by mortise-and-tenon planking combined with frames fastened using internal lashings, active during the Roman period primarily between the 1st century BC and 1st century AD, and its origin remains largely unknown.

La Tour-Fondue (250- 200 BC) Southern France

The La Tour-Fondue shipwreck was found at the tip of the Presqu’ile de Giens, near Hyeres in France, about 20 kilometres southeast of Toulon. It was excavated between 1994 and 1997, with scientific reports published in 1997 and 2001, and a more detailed publication in 2012.

The wreck is dated to the 2nd half of the 3rd century BC. This dating is based on its cargo, which was composed of amphoras from Marseilles, Greco-Italic amphora, and Massalian ceramics ‘à pâte claire’. The wreck is identified as a coastal trading vessel ("batiment de cabotage").

The preserved ship remains measure 4.45 metres in length and from the central part of the boat.

The recorded remains include, a keel, a dozen planking strakes, and eight frames, consisting of alternating floor-timbers and half-frames.

Regarding construction techniques, the planking strakes were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints. The frames were joined to the planking using internal lashings.

The structural characteristics observed in La Tour-Fondue, specifically planking assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints and frames joined by internal lashings, are also seen in other vessels from the Hellenistic or Republican period, such as Cap Bear 3 (third quarter of the 1st century BC), La Roche-Fouras (end 2nd/beginning 1st century BC), Medes 6 (end 2nd/beginning 1st century BC), Dramont C (end 2nd/first half 1st century BC), and Cavaliere (c. 100 BC). La Tour-Fondue, dating to the 2nd half of the 3rd century BC, represents an earlier example within this group of vessels exhibiting this combination of shell-first planking assembly and frames attached with internal lashings.

Cap Bear 3 (c 100 BC) Southern France

The Cap Bear 3 wreck was found in the harbour of Port-Vendres, which is geographically not too far from Dramont, both being on the French Mediterranean coast. This proximity suggests that ships navigating these waters would have faced similar conditions and been part of overlapping trade networks.

Cap Bear 3 dates to the late 2nd century to the early 1st century BC. This timeframe overlaps with the dating of Dramont C.

The primary cargo of Cap Bear 3 consisted of 300 amphorae containing wine produced in the northeastern region of Hispania (modern Spain). The presence of amphorae as a primary cargo is also a key feature of the Dramont C wreck.

Besides amphorae, Cap Bear 3 also yielded a diverse collection of bronze furniture (including parts of couches inlaid with silver and copper, a dish, a bucket with a Bacchic mask, and a candelabrum foot), a Greek inscription (suggesting the origin or influence), a stone mortar and pestle of Cycladic marble, touchstones, a tin oil lamp, Campanian B dishes, and coarse ware jugs and jars. Five small pieces of marble (possibly samples for trade) and wooden discs (likely parts of the ship's pumps) were also found. This variety of artifacts provides insights into the daily life and potential trade goods beyond the primary cargo on such vessels, which could be relevant to understanding the context of the Dramont wrecks.

Cap Bear 3 was a coastal trader estimated at 12–14 metres long, excavated over an area measuring 6 x 1.60 metres. Part of the keel, seven strakes of planking assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints, and 28 frame-timbers attached to the planking with internal lashings were recovered.

The Cap Bear 3 wreck is considered valuable evidence for the significant sea trade conducted between the port cities of Hispania Citerior (Tarraconensis) and Roman cities.

La Roche-Fouras (c 100 BC) Southern France

The La Roche-Fouras shipwreck was found near Cap Camarat, Saint-Tropez, France.

The wreck is dated to the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 1st century BC. This dating is based on the presence of Italic Dressel 1C amphoras found at the site.

The preserved remains of the hull measure 6 x 2 metres. These remains consist of several components, a keel, strakes of hull planking and framing timbers, which include alternating floor-timbers and half-timbers.

The hull planking strakes were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints and the framing timbers (floor-timbers and half-timbers) were joined to the planking with internal lashings.

The lashing system on the Roche-Fouras wreck was not recorded until 1995. This observation occurred when the site was re-opened to take wood samples.

According to the hull remains and the cargo, the La Roche-Fouras wreck is interpreted as a small coastal trader. Its estimated original length was about 10 metres.

Dramont C (125 - 100 BC) Southern France

Dated to approximately 125-100 BC, the Dramont C shipwreck was found off the coast of Dramont about 30 kilometres northeast of St. Tropez on the Chretienne shoal, which is notorious for its wrecks. The dating is from the Dressel 1B amphora found on the wreck, which was produced between 125 and 10 BC.

It was a small coastal boat, estimated to be between 12 and14 metres in length.

The ship was carrying amphorae, ceramics (including ollae, olpes, jars, plates, and cups), and iron bars. Some copper tableware and three millstones were also found. Interestingly, stone slabs interpreted as a workbench for cutting amphora stoppers were discovered.

A preserved section of the hull (6 metres x 1.6 metres) showed ligature attachments, similar to those found on the Cap Bear 3 wreck, indicating a specific shipbuilding technique.

Barthélemy B (c 100 BC – 100 AD) Southern France

The Barthélemy B was found off the coast of Provence. It was a relatively large ship, with an estimated length of about 15 metres, capable of carrying around 300 amphorae. It is dated between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD based on its cargo.

The frames were substantial, measuring between 120 to 150 mm in moulded dimension, similar to the larger Madrague de Giens shipwreck.

The cargo consisted of a fine collection of furniture and sculptural appliques, primarily from bronze couches inlaid with silver and copper. An inscription suggested Greek manufacture. A large dish and a bucket decorated with a fine Bacchic mask. A candelabrum foot and other pieces of bronze furniture. A stone mortar and pestle made of Cycladic marble. Two touchstones. A tin oil lamp. Campanian B dishes and coarse ware jugs and jars. Five small pieces of marble, possibly samples for merchants. Some wooden discs, likely parts of the ship's pumps.

The Barthélemy B shipwreck as an example of the Northwestern Mediterranean Roman Shipbuilding Tradition, known for its use of internal frame lashing, placing it alongside other similar wrecks from the region and period. However, specific archaeological data about Barthélemy B itself, such as its precise date, dimensions, or detailed construction methods, is not yet available.

Mèdes 6 (c 100 BC) Southern France

The Mèdes 6 shipwreck was found between the Presqu’île de Giens and the island of Porquerolles (Hyères, France), about 20 kilometres southeast of Toulon.

The wreck is dated to the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 1st century BC. This dating is based on the presence of Italic Dressel 1C amphoras found on the site.

The remains of the hull measure 4.50 × 2.50 metres and consist of a keel, strakes of hull planking, and framing timbers. The framing timbers include alternating floor-timbers and half-timbers.

The strakes of hull planking were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints.

The framing timbers (floor-timbers and half-timbers) were joined to the planking with internal lashings. The pattern of ligatures, or lashings, is not always regular, a feature also found on the Cavaliere and Barthélemy B wrecks.

According to the hull remains and the cargo, Mèdes 6 is interpreted as a small coastal trader with an original length of about 10 metres.

Catalonia and Languedoc Shipbuilding Tradition

Although part of the Northwestern Mediterranean tradition, the ships from the Catalonia and Languedoc region are distinguished by several characteristics, particularly regarding their construction techniques and areas of operation. They represent a local tradition developed to address fluvio-maritime conditions, influenced by first Greek (Hellenistic) and then Roman shipbuilding techniques.

Internal Frame Lashing: The most prominent distinguishing feature for ships found in the Northwestern Mediterranean area, including Catalonia and Languedoc, is the technical solution of using internal lashings to fasten the framing timbers to the planking. This technique is consistently observed across numerous vessels in this broad region. This method is considered a defining characteristic of a technical tradition that appears to have been grafted onto various previous architectural traditions present in the northwestern Mediterranean, rather than being tied to a single, specific cultural or shipyard "fingerprint" with a clear origin. Fragments found in Port La Nautique (Narbonne) and Port-Vendres 3 (Languedoc/Roussillon) also belong to this technical tradition, showing frames fastened with internal lashings locked by treenails.

Internal Luting and Pitch: A second group of boats from Catalonia and Languedoc, which includes Perduto 1 and Cala Cativa 1, is further characterised by a specific construction feature: the use of internal luting on the frames and also on the outboard surface of the planking. These luted areas are filled with a coat of pitch. The system is then secured by the addition of single treenails, sometimes supplemented by nails, typically in a more-or-less regular pattern.

Ships from this region are associated with fluvio-maritime zones, operating in the networks of rivers and coastal lagoons stretching from the Ebro River to the Rhône River. Within this technical tradition and geographical area, different architectural types are found. This includes both fluvio-maritime ships (such as Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer 2 and 24, Cap del Vol, Baie de l’Amitié, and Cala Cativa 1) and small coastal boats (like the Palamos). While primarily adapted for these regional waterways, some vessels from this group, specifically Perduto 1, could also be involved in offshore navigation. They are generally described as medium-sized sailing vessels, though exceptions like the smaller Cala Cativa 1 exist.

This northwestern Mediterranean technical tradition, defined by its internal frame lashings, is presented as distinct from others. For instance, the use of internal lashings in this region contrasts with the external lashings used in the Iberian tradition, representing different construction principles. While some ships from this region are dated within the Roman period, they embody different construction methods compared to the Western Roman Imperial type which relied on mortise-and-tenon joints and evolved towards incorporating more structural framing from the 2nd to the 5th centuries AD.

Palamós (c100 – 50 BC) Catalonia, Spain

The Palamós shipwreck is situated near the Isle of Formigues, which is off the coast of Girona, in Catalonia, about 60 kilometres northeast of Barcelona. The wreck is dated to the first half of the 1st century BC.

The hull planking strakes were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints and the frames were joined to the planking with internal lashings.

The wreck's cargo was from Catalonia.

Plane 1 (c 50 BC) Marseilles

The Plane 1 shipwreck was discovered in the Marseilleveyre archipelago, located at the entrance of the Bay of Marseilles. It is dated to the middle of the 1st century BC. This dating is based on the presence of Dressel 1B amphoras and pre-Aretine ceramics found at the site.

The hull of the Plane 1 shipwreck was partially recorded over an area of 4.50 × 3 metres during a dendrochronological study conducted in 1992.

The remains that were recorded include, a mast-step timber, ceiling planks, hull planking assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints, and frames, which consisted of alternating floor-timbers and half-floors, attached to the planking with internal lashings.

The keel and garboards of the vessel are missing, which is noted as potentially having been lost during the sinking.

The use of internal lashings to attach the frames to planking assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints aligns this wreck with other vessels of the Hellenistic or Republican period. For example, the Cap Bear 3 wreck, dated to the third quarter of the 1st century BC, also exhibits a hull structure characteristic of this period with mortise-and-tenon planking and frames joined by internal lashings and treenails. Similarly, wrecks like La Tour-Fondue (dated to the second half of the 3rd century BC), La Roche-Fouras and Mèdes 6 (dated to the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 1st century BC), and Palamós (dated to the first half of the 1st century BC) also show planking assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints and frames joined with internal lashings.

Cap del Vol (early 1st century AD) Catalonia, Spain

The Cap del Vol wreck is situated at Cap del Vol near Cap Creus in Catalonia. The wreck is dated to the beginning of the 1st century AD based on the ceramics and Pascual 1 Spanish amphoras found at the site.

The remains were studied over an area measuring 8.50 × 6 metres. The preserved parts include the aft part of the boat, the keel, and the sternpost. Additionally, a dozen frames were present, made up of floor-timbers regularly alternating with half-frames. A mast-step timber was also recorded.

Construction of the Cap del Vol:The planking was fastened by mortise-and-tenon joints.

The keel is described as relatively flat, with a height of only 60mm and a width of 120mm.

A key characteristic observed is how the frames were attached to the planking. The frames are fastened using single treenails or nails which are more-or-less regularly alternated with pairs of treenails joined by grooves filled with pitch visible on the inboard face of the frames and outboard face of the planks. This pattern clearly indicates the use of internal lashings. The use of internal lashings was confirmed when the wreck was re-examined in 2011–2012.

Based on its structural characteristics, particularly its flat keel and bottom, the Cap del Vol shipwreck is identified as a fluvio-maritime vessel. It is considered to be of a type adapted to navigating the coasts of Catalonia and the Narbonne region, as suggested by its cargo. The reconstructed length of the vessel is estimated to have been 18–20 metres.

The Cap del Vol wreck belongs to the Northwestern Mediterranean technical tradition, specifically the group of ships from the Catalonia and Languedoc region. Its defining characteristic within this tradition is the use of internal lashings to fasten the framing timbers to the planking. It is also mentioned alongside other vessels (like Perduto 1) that could be involved in offshore navigation, although its primary adaptation was for regional waterways. The wreck is considered to be of the same type and construction as the Los Ullastres wreck.

Los Ullastres (1st century BC to 1st century AD) Catalonia

The Los Ullastres wreck is situated near the isle of Formigues, in Catalonia, near Girona. The wreck is dated to the end of the 1st century BC–beginning of the 1st century AD.

Construction Characteristics (shared with Cap del Vol and Perduto 1): Planking assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints.

Frames attached using internal lashings.

While it is believed to have frames attached using internal lashings like Cap del Vol and Perduto 1, the means of fastening the frames on Los Ullastres has not yet been observed directly.

Perduto 1 (1st century BC to 1st century AD) Corsica

The Perduto 1 wreck was found at the entrance to the Strait of Bonifacio between Corsica and Sardinia. It was carrying a cargo of Dressel 2/4 amphorae from Tarraconensis (Catalonia). This, together with its type of construction, place it in the Catalonia and Languedoc shipbuilding tradition. It is likely that vessels of this particular design, although primarily designed for use in the deltaic areas of the Rhone and Ebro, did have a seagoing capability.

Perduto 1 is described as a medium-sized sailing vessel.

Construction Characteristics (Specific to this Group):The use of internal luting on the frames. Internal luting was also applied to the outboard surface of the planking. These areas of luting are filled with a coat of pitch.

The system is completed by the addition of single treenails, and sometimes nails, in a more-or-less regular pattern.

In summary, the Perduto 1 shipwreck is a representative of a specific regional shipbuilding group from Catalonia and Languedoc (1st century BC - 1st century AD). Its significance lies in demonstrating a particular construction technique involving internal luting filled with pitch, complemented by treenails and sometimes nails. It is considered a medium-sized sailing vessel capable of both regional fluvio-maritime and offshore navigation.

Saintes-Maries 2 (1 – 25 AD) River Rhone Estuary, Southern France

The Saintes-Maries 2 wreck was found close to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer 24 in the mouth of the Rhône River in the Camargue, France. It is dated to the first quarter of the 1st century AD.

Hull Construction of the Saintes-Maries 2:The study of the preserved small part of the hull enabled the recording of the flat bottom.

Crucially, the fastening system of the frames to the planking was recorded. Both Saintes-Maries 2 and Saintes-Maries 24 have their frames fastened to the planking using internal lashings.

Based on its characteristics, Saintes-Maries 2 is identified as a fluvio-maritime vessel.

Its estimated length is 15–18 metres.

The vessel type and its characteristics indicate it was suited to navigating the lagoonal coasts of Languedoc and the Rhône delta. The site where the wreck was found aligns with this navigation area.

The vessel carried a cargo of iron bars and ingots. This cargo originated from the Montagne Noire, north-west of Narbonne, where it had probably been loaded on board. The provenance of the cargo matches the vessel's capabilities and the wreck's site.

Saintes-Maries 24 (c 50 AD) River Rhone Estuary, Southern France

The Saintes-Maries 24 wreck was discovered near Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer 2 in the mouth of the Rhône River, situated within the Camargue region of France.

Based on the archaeological material, the vessel is dated to around the middle of the 1st century AD.

Construction of Saintes-Maries 24: The hull features a keel plank that is wider than it is deep.

It has a flat bottom. The hull is composed of 12 planking strakes. These strakes were assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints. There are 26 frames, made up of floor-timbers and half-frames. Notably, these frames are arranged in no regular pattern. A key construction feature is how the frames are attached to the planking: the frames are fastened using internal lashings. The lashing system includes grooves filled with pitch.

Its estimated length is between 20 and 25 metres.

Vessel Type, Size, and Navigation: Based on its characteristics, Saintes-Maries 24 is identified as a fluvio-maritime vessel.

The type and size of Saintes-Maries 24 indicate that it was suited to navigating the lagoonal coasts of Languedoc and the Rhône delta. The location where the wreck was found aligns with this suggested navigation area.

Baie de l’Amitié (1 – 50 AD) Southern France

The Baie de l’Amitié shipwreck was discovered near Cap d’Agde, Southern France. The wreck is dated to the second half of the 1st century AD. This dating is based on its cargo that consisted of olive oil contained in Dressel 20 amphoras. The ship also carried a cargo of lead ingots and Gaulish terra sigillata.

Hull Remains and Construction: The preserved hull remains cover an area of 9 × 4.5 metres. The structure includes a flat bottom with a keel plank and the base of the stem. Fifteen planks were preserved. The planking is assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints.

There are 25 frames present, which alternate between floor-timbers and half-frames, fastened to the planking using internal lashings.

A stringer was also found.

Regional Context: The Baie de l’Amitié shipwreck belongs to a group of vessels found in the fluvio-maritime zones of Catalonia and Languedoc, spanning from the Ebro River up to the Rhône River.

Cala Cativa 1 (1 – 50 AD) Catalonia

The Cala Cativa 1 shipwreck was discovered near Cap del Vol, Cap Creus, in Catalonia. The wreck dates to the first half of the 1st century BC.

It is described as a metres with an estimated length of about 7 metres. This size distinguishes it as an exception within its regional group, which generally consists of medium-sized sailing vessels.

Hull Construction: The boat features a flat bottom with a flat keel. A significant construction characteristic is the presence of internally lashed frames.

Western Roman Imperial Type

Roman Cargo Ship Cutaway - National Museum of Underwater Archaeology - Cartagena

The shipbuilding technique and architectural type that succeeded the dominant Hellenistic system during the Roman Empire, particularly in the Western Mediterranean, was the Western Roman Imperial type.

The Hellenistic type, which was prevalent during the Hellenistic period and Roman Republic, featured a tripartite structure (keel, planking, framing) often with a wine-glass cross-section and planking assembled by pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. It also presented a structural weakness at the keel level. The Western Roman Imperial type, emerging later during the Roman Empire, presented a new architectural approach.

Key Construction Features of the Western Roman Imperial type

A flat bottom section amidships with a round turn of the bilge.

Internal framing that is more significant and largely reinforced transversely.

Overlapping frames, specifically alternating floor-timbers and half-frames, which often overlapped the keel axis, contributing to structural strength.

A keelson/mast-step timber fitted on lateral sister-keelsons, unlike the earlier Hellenistic method where the mast-step was often fitted directly on the floor timbers.

A strong arrangement of pegged mortise-and-tenon joints for planking.

When did the Western Roman Imperial type develop?

This new type began to appear in the Western Mediterranean from the 2nd century AD. The emergence of this type with "very partial mixed processes" of construction is evident in shipwrecks like Saint-Gervais 3 and La Bourse from the mid-2nd century AD.

Still generally based on a shell concept (where the planking largely defines the hull shape), the Western Roman Imperial type showed greater transverse reinforcement by the framing and some longitudinal reinforcement. It represents a move towards reinforcing the framing and shows the first evidence of possible partially active frames and a limited mixed construction process, marking an early stage towards the transition from shell to skeleton construction.

Although the Western Roman Imperial type became dominant in the Western Mediterranean, the Hellenistic type did not disappear entirely and endured in the Eastern Mediterranean until at least the Early Byzantine period. The transition from shell to skeleton construction was a long and complex process involving different "roots" or evolutionary paths in various regions of the Mediterranean. The Western Roman Imperial type represents one significant root of this transition.

La Bourse (190 – 220 AD) Marseilles

The La Bourse shipwreck was found in the 'Vieux Port' of Marseilles, in the horn of the ancient creek of Lacydon. Its discovery occurred during the construction of the new Centre de la Bourse. The wreck is dated to 190–220 AD.

The archaeological remains that were found measured 20 metres long by 7 metres wide. The reconstructed dimensions of the ship suggest it was originally 23 metres long by 9 metres wide.

Construction details of La Bourse: The hull section of the La Bourse wreck had flat frames and a round turn of the bilge.

The keel was trapezoidal in shape. Its dimensions were 17–28 cm sided and 29 cm moulded. The keel was also chamfered along its entire length. This chamfering gradually changed to rabbets in the endposts.

The planking was assembled with a close set of mortise-and-tenon joints, with spacing between mortises frequently equal to or not exceeding 2.3 times the mortise width. There was evidence of pegs locking the tenons, with some potentially driven in the reverse direction.

The La Bourse wreck date (190–220 AD) places it in the later Roman Imperial period compared to the earlier vessels like La Tour-Fondue or Cavaliere that exhibit planking with mortise-and-tenon joints and frames attached by internal lashings. The description of its flat frames with a round turn of the bilge aligns it with other Roman Imperial types discussed, such as Saint-Gervais 3, Laurons 2, Monaco A, Pointe de la Luque B, Fiumicino 1, and Port-Vendres I, which also display this characteristic hull form.

Saint-Gervais 3 (c 175 AD) Southern France

The Saint-Gervais 3 wreck was found near Saint-Gervais in the Golfe de Fos in southern France. It was located at a depth of 4 metres. The wreck was dated to the mid-2nd century AD by amphoras with tituli picti.

Construction of Saint-Gervais 3: The remains of the vessel were 14.7 metres long and 6.8 metres wide. Its reconstructed original dimensions are estimated at 17 metres long with a maximum beam of 7.5 metres.

The transverse section of the hull at the main frame featured a flat frame with a round turn of the bilge.

A hypothetical reconstruction suggests a concave stem.

The hull belonged to the structural system classified as the western Roman Imperial type.

It exhibited a strong arrangement of pegged mortise-and-tenon joints.

The internal framing was more significant compared to that of the earlier Hellenistic type.

The construction shows evidence of very partial mixed processes.

Saint-Gervais 3, along with La Bourse, shows very partial mixed processes.

Laurons 2 (c 200 AD) Southern France

The Laurons 2 shipwreck was found in the Anse des Laurons in the Golfe de Fos, southern France. It lies at a depth of 2.5 metres. It was re-opened and reconsidered during dendrochronological research in 1994.

The wreck is traditionally dated to the end of the 2nd century AD. It was recently re-dated to the end of the 3rd century based on a coin and ceramics among the crew's possessions, but the coin's identification is still open.

The surviving remains measured 13.3 metres long and 6 metres wide at the master-frame. The reconstructed dimensions of the hull suggest it was 15 metres long by 5 metres wide.

The main significance of Laurons 2 lies in the surviving remains of the upper part of the hull, including the deck and above the bulwark and its stanchions.

The transverse section of the hull had flat frames with a round turn of the bilge.

Construction Details of the Laurons 2: The hull shows a shell structural concept and a longitudinal, strake-oriented hull-shape, contrasting with the integrity of a skeleton-based construction. The building process was very probably shell-first.

Planking was assembled with mortise-and-tenon joints. Details of repairs between strakes 10 and 11 were scrutinized.

Frames were connected to the planking by pairs of treenails.

Bolts connecting some floor-timbers were likely for reinforcement, such as those on keel/endpost scarfs, rather than indicating active frames. There was no evidence for the hypothesis of an 'alternating construction' (mixed skeleton-first) as proposed by some earlier work.

The hull was made watertight by an internal coat of pitch.

The Laurons 2 hull belonged to the new western Roman Imperial type. This type is characterized by a flat bottom and reinforced framing. It is presented as a characteristic example of this type, alongside the La Bourse shipwreck.

Monaco A (c 200 – 250 AD) Monaco

The Monaco A shipwreck was found in Monaco harbour in 1948. The wreck is dated to the end of the 2nd century or the first half of the 3rd century AD.

The preserved remains were approximately 8.4 metres long, found in two sections, and were 1.2 metres wide. Originally, the ship was probably not more than 15 metres long.

The midship section of the hull had a flat floor-timber with a round turn of the bilge.

Construction Details of Monaco A: The hull planking consisted of planks that were 18–27 cm wide and 30–40 mm thick.

Planks were connected to each other and possibly to the keel using pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. The mortises were 60 mm wide, 7 mm thick, and 40 mm deep. Tapered pegs, 70–80 mm long, were used to lock these tenons in their mortises.

The Monaco A hull was built based on a longitudinal and shell structural concept.

An earlier reconstruction proposed after a study in 1965 raised questions, particularly regarding the interpretation of treenails in the keel-scarf and the positioning of floor-timbers and a supposed keelson.

It is noted that treenails observed in the keel-scarf were likely for reinforcing this major joint, similar to other shipwrecks, rather than connecting elements as previously proposed. Similarly, a bolt connecting a floor-timber to the keel, which was considered as an example of an active frame in some interpretations, was more probably for reinforcing the endpost scarf.

There is the possibility that the Monaco A could have had active frames, representing a limited mixed construction process as a skeleton solution within the shell-first approach.

The Monaco A is included as an example of the western Roman Imperial tradition, which is characterized by flat frames and a round turn of the bilge. It is considered, potentially, as a vessel that might show some of the first evidence of possible partially active frames and a limited mixed construction process within this ship type.

Pointe de la Luque B (300 – 400 AD) Marseilles

The Pointe de la Luque B shipwreck was discovered at the south-western end of Pomègues Island, Frioul Archipelago, in the Bay of Marseilles. The wreck is dated to the 4th century AD.

The surviving forward hull remains measured 8 metres long and 5 metres wide. The estimated original dimensions of the hull were 20 metres long and 6 metres wide.

The hull had a cross-section characterised by flat frames with a round turn of the bilge.

Construction Details of the Pointe de la Luque B :The keel was 13 cm sided and 17 cm moulded, and it featured a rabbet for the garboard. The garboard plank was a maximum of 55 mm thick.

The planks themselves were between 150–230 mm wide and 30 mm thick and were connected to each other and to the keel using pegged mortise-and-tenon joints.

The mortises were specifically measured at 60 mm wide, 7 mm thick, and 40 mm deep.

Tapered pegs were used to secure the joints.

Evidence was found for the remains of four wales, which were typically 160 mm wide and 160 mm thick and connected to the hull.

Fiumicino 1 (390 – 410 AD) Rome

The Fiumicino 1 shipwreck, also known as Oneraria Maggiore 1, was discovered in 1960 during the construction of the international airport at Fiumicino, Rome, near the site of the ancient harbour of Claudius. Its sister ship, Fiumicino 2, and Fiumicino 3, which was of the same type but slightly smaller, were also found at this location. The wreck is dated to the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 5th century AD.

The preserved remains of Fiumicino 1 measured 13.83 metres long by 4.57 metres wide. Based on these remains, the reconstructed ship is estimated to have been 17.18 metres long (overall) and 5.6 metres wide.

Regarding the hull structure, the midships section had flat frames and a round turn of the bilge.

A notable construction detail of Fiumicino 1 is that it was a particular case characterised by the absence of longitudinal axial components, with the exception of a small forward keelson which served as a towing post step. This specific feature may have been a result of riverine influence, classifying the vessel as a sea-river ship. The treenails observed in the keel scarf on Fiumicino 1 are noted to be for reinforcing this joint, similar to those found on other shipwrecks like Madrague de Giens, rather than connecting elements in a different structural manner. Additionally, tangential iron nails were used to connect the garboard to the keel.

Dramont F (350 – 400 AD) Southern France

The Dramont F shipwreck is located off Cape Dramont in southern France, near Saint-Raphaël. It is dated to the second half of the 4th century AD and is considered a possible late evolution of the western Roman Imperial type of shipbuilding tradition.

The available remains consist of a section of the hull measuring 1.10 metres long and 2.1 metres wide.

Based on the observed remains, the original estimated length of the ship was between 10 and 12 metres.

The hull cross-section seems to have featured flat floor-timbers and a round turn of the bilge. These shape characteristics are notable as they align with descriptions of the Western Roman Imperial type.

The keel of Dramont F was trapezoidal in shape, measuring 95 mm sided at the bottom, 105 mm at the top, and 145 mm moulded, with chamfered corners for the garboards.

The ship used pegged mortise-and-tenon joints, though there were exceptions. The vessel had widely spaced mortise-and-tenon joints and loose tenons, and sometimes unpegged joints were used. The framing system was based on floor-timbers. There was also a strong axial longitudinal timber, identified as a reconstructed keelson.

Dramont F is described as having a shell concept, though with a mixed construction process. Its widely spaced and loose/unpegged mortise-and-tenon joints are interpreted as representing an intermediate step of evolution leading progressively to a mixed process of building within this potential late Western Roman Imperial type.

Parco di Teodorico (350 – 400 AD) Ravenna, Italy

The Parco di Teodorico is a Late Roman shipwreck located in Ravenna, Italy with dates broadly similar to other Late Roman vessels discussed (e.g., Dramont F, which is a late 4th/early 5th century AD).

The Parco di Teodorico wreck demonstrates the problems and evidence related to the transition from shell-first to skeleton-first construction methods in the ancient Mediterranean.

The hull of the Parco di Teodorico shipwreck was built according to a shell concept for the shape, combined with a structural concept on frames. It is presented as a good example of the combination of a mixed transitional concept and technique. It demonstrates principles that are still plank-oriented and uses a shell-first construction method. However, the frames in this vessel provide the hull integrity, indicating a shift away from pure shell construction. The construction does not yet represent full skeleton construction.

The Parco di Teodorico shipwreck is significant as a well-documented example demonstrating a mixed, transitional shipbuilding concept in the Late Roman period, where frame use becomes crucial for hull integrity while still retaining elements of shell-first principles. It represents an evolutionary step in ancient Mediterranean shipbuilding, potentially linked to the later stages of the western Roman Imperial tradition.

Pointe de la Luque B (4th century AD) Marseilles

The wreck was found at the south-western end of Pomègues Island, which is part of the Frioul Archipelago in the Bay of Marseilles. It is dated to the 4th century AD. This dating was established during a dendrochronological project conducted in October 1992, which provided new, previously unpublished information.

The surviving forward hull remains covered an area of 8 metres long and 5 metres wide.

The estimated original dimensions of the hull were 20 metres long and 6 metres wide.

Hull Construction of Pointe de la Luque B: The vessel's cross-section featured flat frames with a round turn of the bilge.

The keel was 13 cm sided and 17 cm moulded and included a rabbet for the garboard. The garboard plank had a maximum thickness of 55 mm.

The hull planks were between 150 mm and 230 mm wide and 30 mm thick. Planking was assembled using pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. The mortises measured 60 mm wide, 7 mm thick, and 40 mm deep. Tapered pegs were used to connect the planks to each other and to the keel.

There was evidence of the remains of four wales, typically 160 mm wide and 160 mm thick.

The Pointe de la Luque B shipwreck was constructed with a shell concept and process and is an example of the evolution towards complete skeleton construction in ancient Mediterranean shipbuilding.

Increasing Size of Vessels during the Roman Period

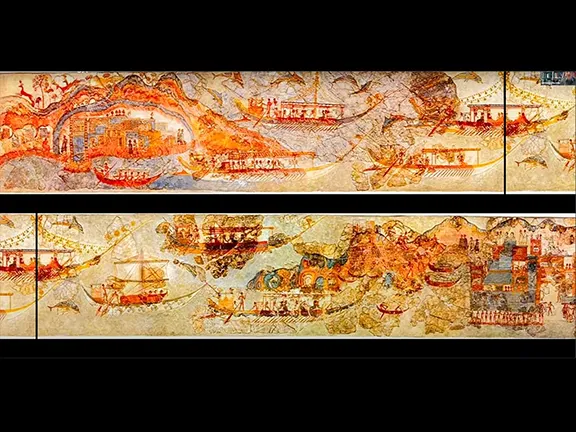

Roman Fresco of the Isis

In the Roman period (mid-3rd century BC to 4th century AD), shipbuilding continued techniques from the Hellenistic era. The increasing demand for cargo space resulted in bigger merchant ships during the early part of this period. Examples include the first-century BC shipwrecks of La Madrague de Giens (400 tonnes) and Albenga (500-600 tonnes).

However, towards the later Roman period, a tendency emerged to favour less costly and faster construction methods, possibly linked to factors like the decline in slavery. Consequently, ship owners preferred smaller and cheaper vessels, and wrecks of big merchant ships are uncommon after the second century AD. For instance, the Yassi Ada Byzantine shipwreck of the 4th century AD, is described as a small cargo vessel with an estimated original length of around 20 metres.

The Isis on the other hand, was a larger than typical mid to late Roman Empire grain ship. We are fortunate that its description was captured by a sophist whilst it was in port at Piraeus.

Isis (mid to late Roman Empire) Sicily

Description by Lucian

The Roman ship Isis was an exceptionally large vessel for its time, described by the sophist Lucian, who saw it in the port of Piraeus (Athens), as being around 55 metres long with a beam of approximately 13.7 metres. Its hold was about 13.4 metres deep.

It was an Alexandrian grain ship, primarily used to transport grain from Egypt to Italy, a crucial trade route for the Roman Empire's food supply.

It’ s carrying capacity was estimated to be around 1,071 tonnes.

The ship was named after the Egyptian goddess Isis, as evidenced by figures of the goddess on either side of the stern.

The Wreck Site and Discovery

The wreck was found in deep water (around 750 metres) off the northwest coast of Sicily, near a reef called Skerki Bank. This area appears to have been a hazardous location for ships throughout history, with several other ancient wrecks discovered nearby.

The discovery by Robert Ballard, the same oceanographer who found the Titanic, was a landmark in deep-sea archaeology. The use of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) like Jason and Medea was crucial for surveying and excavating the site at such depths.

Cargo and Significance

While a complete and definitive cargo list isn't always straightforward for ancient wrecks due to scattering and degradation over time, evidence suggests the Isis was carrying grain, consistent with its historical description.

Archaeological investigations recovered around 10 amphorae from the site, some possibly originating from Tunisia and Calabria. These would have likely contained other goods alongside the bulk grain cargo, such as wine or oil.

The wreck also yielded three or four iron anchors and hull remains indicating a "shell-first" shipbuilding method common in antiquity. A lead patch found suggests the ship might have been old and undergoing repairs.

Evolution of the Warship in the Mediterranean during the Roman Period

The evolution of the warship in the Mediterranean Sea between 264 BC and 400 AD was a dynamic process shaped by technological innovation, strategic needs, and the changing political landscape.

The Dominance of the Oared Galley (c. 264 BC - 1st Century AD)

The Quinquereme: At the beginning of this period, particularly during the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage, the quinquereme was a dominant warship. This type of galley had three banks of oars with multiple rowers per oar, providing significant speed and manoeuvrability.

Ramming Tactics: Naval warfare heavily relied on ramming enemy ships. Galleys were equipped with bronze rams at the waterline designed to pierce and sink opposing vessels.

Boarding Actions: Recognizing their initial disadvantage in naval tactics compared to Carthage, the Romans adapted by focusing on boarding actions. They famously introduced the corvus, a hinged boarding bridge with a spike named after the raven’s beak, allowing Roman legionaries to turn sea battles into land battles where they excelled. This innovation played a crucial role in Roman naval victories during the First Punic War.

Early Roman Fleets: Initially not a major naval power, Rome rapidly built its fleets by copying and adapting Carthaginian designs. They learned to construct large numbers of galleys relatively quickly.

The Rise of Smaller Vessels: Over time, while larger galleys remained important, smaller and more manoeuvrable vessels like the liburna discussed above, adopted from Illyrian pirates, gained prominence, particularly in Roman provincial fleets. Liburnae were biremes (two banks of oars) known for their speed and agility.

Transition and Diversification (1st Century AD - 4th Century AD)

The Battle of Actium (31 BC): This pivotal naval battle saw the continued use of galleys, including those equipped with artillery like ballistae and the harpax, a catapult-launched grappling hook.

Pax Romana and Naval Roles: With the establishment of the Roman Empire and the Pax Romana, large-scale fleet battles became less frequent. The Roman navy's role shifted towards patrol, suppressing piracy, transporting troops, and maintaining sea lanes.

Smaller, Specialized Vessels: The trend towards smaller, more specialized vessels continued. Different types of galleys and other oared ships were used for various purposes, including scouting, riverine operations, and troop transport.

Decline of the Quinquereme: The massive quinqueremes gradually became less common, potentially due to their high crew requirements and the changing nature of naval warfare. The trireme (three banks of oars, one rower per oar) became a more standard large warship.

Limited Innovation in Large Warships: Compared to the earlier period, there was less radical innovation in the design of large Mediterranean warships during the Roman Empire. The focus was more on maintaining existing fleet capabilities and adapting vessel types to specific regional needs.

Significant Naval Battles in the Mediterranean during the Roman Period

Between 264 BC and 400 AD, the Mediterranean Sea was the stage for several significant naval battles that employed the latest design of warships. These battles shaped the course of history.

The Punic Wars (264-146 BC)

These wars between Rome and Carthage were largely fought for control of the Mediterranean and featured numerous naval engagements.

Battle of Mylae (260 BC): Rome's first major naval victory, where they used the corvus to overcome Carthage's superior naval tactics. The Romans had around 100 warships. These were primarily quinqueremes (the standard heavy warship of the time, meaning "five-oared," with multiple rowers per oar) and some triremes. The Carthaginians had around 130 warships, mostly quinqueremes and likely some smaller galleys.

Battle of Cape Ecnomus (256 BC): Possibly the largest naval battle in antiquity by the number of ships and combatants, resulting in a decisive Roman victory and paving the way for their invasion of Africa. The Roman fleet consisted of approximately 330 warships, mainly quinqueremes, plus a large number of transports. Estimates suggest around 140,000 men were involved (rowers and marines). The Carthaginian fleet had around 350 warships, predominantly quinqueremes, with an estimated 150,000 men.

Battle of Drepana (249 BC): A significant Carthaginian victory where the Roman fleet was caught off guard and suffered heavy losses.

Battle of the Aegates Islands (241 BC): The final naval battle of the First Punic War, a decisive Roman victory that forced Carthage to sue for peace. The Roman fleet was newly built and financed by private contributions, the first recorded instance of such an arrangement. The fleet had about 200 warships, primarily quinqueremes. The Carthaginian fleet was intended to resupply their forces in Sicily and consisted of about 250 warships, again mainly quinqueremes.

Much of the Second Punic War, and the battles that proved decisive, was fought on land.

Battle of Lilybaeum (218 BC): This first naval engagement of the Second Punic War saw 35 quinqueremes from Carthage engaged on a raid on Sicily. The fleet was intercepted by a Roman force of 20 quinqueremes. The Romans captured several Carthaginian ships and thwarted the raid.

Battle of Carteia (206 BC): Carteia was a major Carthaginian port at the mouth of the River Palmones that flows into the Bay of Algeciras in southern Spain. It was the last naval engagement of the Second Punic War and more accurately described as a skirmish between one quinquereme and seven triremes on the Roman side and one quinquereme and eight triremes on the Carthaginian side. After losing two triremes, the Carthaginian commander conceded defeat.

The Roman Civil Wars (throughout the 1st century BC)

The tumultuous period of the late Roman Republic saw several important naval clashes, the most significant being the Battle of Actium.

Battle of Actium (31 BC): A pivotal battle where the forces of Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) decisively defeated the combined fleets of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. This victory marked the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

Sources suggest that the Octavian fleet had between 250 and 400 warships. His fleet was composed of lighter and more manoeuvrable vessels, mainly liburnae (smaller, faster biremes adopted from Illyrian designs) and some triremes.

Opposing him, Mark Antony and Cleopatra had an estimated 170 to 500 warships, including larger and heavier vessels like quadriremes, quinqueremes, and even some larger multi-oared galleys (up to octeres or decaremes, though these likely formed a smaller portion of the fleet). Cleopatra's contingent included around 60 Egyptian ships.

Both sides also had numerous supply ships.

While the period after the establishment of the Roman Empire (after 31 BC) was generally more peaceful in the Mediterranean ("Mare Nostrum" - Our Sea), there were still naval actions, primarily focused on suppressing piracy and maintaining order. Battles on the scale of Actium were less frequent during the height of the Empire.

The Dawn of New Designs (Late 4th Century AD)

Model of a Dromon

The Dromon

Towards the end of this period and into the early Byzantine era, a new type of galley, the dromon, began to emerge as a key warship. While still oared, the dromon was generally smaller and faster than earlier large galleys. Key features included lateen sails (triangular sails attached to long yardarms) which offered better performance in various wind conditions, and potentially the use of "Greek fire," an incendiary weapon. The dromon would become the dominant warship of the Byzantine Empire in the following centuries.

In summary, the evolution of the warship in the Mediterranean Sea between 264 BC and 400 AD saw a shift from large, ram-focused galleys like the quinquereme to a greater diversity of vessel types, including smaller and more agile ships. The Romans initially adapted their land-based military tactics to naval warfare but later focused on maintaining sea control and specialized naval roles within their empire. By the end of this period, the precursor to the Byzantine dromon was appearing, signalling the next phase in Mediterranean naval warfare.

References

Bass, G. F. (2011). The Development of Maritime Archaeology. The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology

Casson, Lionel. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton University Press, 1995.

Ferrill, Arther. "The War of Actium." Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1969, pp. 179-208.

Gardiner, Robert, and J. S. Morrison, eds. The Age of the Galley: Mediterranean Oared Vessels since Pre-Classical Times. Conway Maritime Press, 1995.

Goldsworthy, Adrian. The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146 BC. Cassell, 2003.

Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. University of California Press, 1990

Miles, Richard. Carthage Must Be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Civilization. Penguin Books, 2010.

Morrison, J. S., and J. F. Coates. The Athenian Trireme: The History and Reconstruction of an Ancient Greek Warship. Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Pomey, P. et al. (2012). Transition from shell to skeleton in the ancient Mediterranean. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 41(2), 235–314.

Pomey, P., & Boetto, G. (2019). Ancient Mediterranean Sewn‐Boat Traditions. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 48(1), 6-51

Pryor, John H., and Elizabeth M. Jeffreys. The Age of the Dromon: The Byzantine Navy ca. 500-1204. Brill, 2006.

Rodgers, William Ledyard. Greek and Roman Naval Warfare: A Study of Strategy, Tactics, and Ship Design from Salamis (480 B.C.) to Actium2 (31 B.C.). Naval Institute Press, 1937.

Tarn, W. W. "The Fleets of the First Punic War." The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 27, 1907, pp. 48-60.

Tilley, Alec (2020). Shipwrights and Shipbuilding in the Ancient Mediterranean, 700-400 BC (Doctoral dissertation). University of Toronto.

Whitby, Michael. "The Legacy of Sea Power in the Roman East, AD 300-641." In War and Society in the Roman and Byzantine Worlds, edited by John Haldon and Lawrence Conrad, 151-186. Brill, 1992

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture 2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC  3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC

3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC 4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC

4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC 5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC

5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC 6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC

6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC