Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

Bronze and Iron Age Dawn of Naval Architecture in the Mediterranean

Bronze and Iron Age Mediterranean shipbuilding (3000-300 BC). Analysis of hull construction methods, ship design evolution, and insights from shipwrecks, models and ancient art.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-04-24 | Last Updated 2025-05-23 | Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 2,795 times

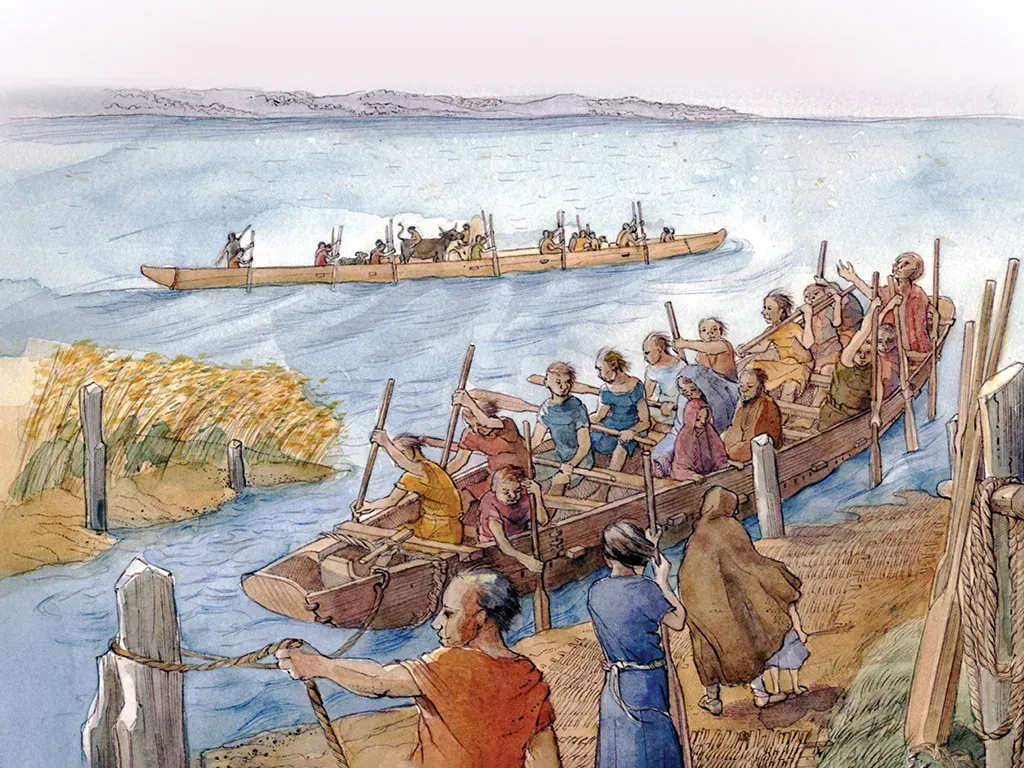

Early canoes

The Bronze Age Mediterranean and the Dawn of Nautical Technology

The Bronze Age Mediterranean, spanning from 3000 to 1200 BC, represents a pivotal era in human history, marked by significant advancements in technology, the rise of complex societies, and an intensification of inter-cultural exchange. A defining characteristic of this period was the burgeoning of maritime activity, which served as the primary means of connecting the diverse cultures inhabiting the Mediterranean basin. The exchange of goods, resources, and ideas across the sea played a crucial role in shaping the economic, social, and political landscapes of the time. Ships were not merely tools of commerce and transport; they were also instrumental in warfare, exploration, and the dissemination of cultural influences.

The study of ancient shipwrecks provides a unique window into the past, preserving not only the goods transported but also crucial evidence of the vessels themselves and the methods employed in their construction. By meticulously analysing the materials and techniques used in shipbuilding, researchers can glean information about the available resources, the skills of the artisans, and the intended purpose and capabilities of these ancient mariners' vessels.

The chronological focus of this analysis spans from 3000 BC to 400 AD, encompassing the Early, Middle, and Late Bronze Ages, and extending into the Iron Age and the period of Roman domination of the Mediterranean. This 3400-year period marks a critical phase in the development of seafaring, potentially transitioning from simpler forms of watercraft to more complex and seaworthy ships capable of undertaking extended voyages across the open sea. Observing the shifts in shipbuilding practices over this significant timeframe can illuminate the gradual advancements in naval architecture and the increasing mastery of the marine environment.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Methodological Considerations in Analysing Ancient Shipwreck Hull Remains

The preservation of organic materials, such as wood, in the marine environment presents significant challenges for archaeologists. Consequently, the survival of substantial portions of ancient ship hulls is often limited. Many shipwrecks from the Bronze and Iron Ages are primarily identified by their more durable cargo, such as ceramic vessels or metal ingots, rather than by extensive remains of the wooden structure itself. This necessitates a careful and nuanced approach to interpreting the archaeological record.

Despite the often-fragmentary nature of the evidence, the meticulous excavation and analysis of even small remnants of a ship's hull can yield crucial information. For example, a seemingly minor artifact, such as a single wooden tenon, can provide vital clues about the joinery techniques employed and, by extension, the overall construction methods utilized in the vessel's creation. Modern archaeological practices emphasize detailed recording, comprehensive photography, and rigorous material analysis to extract the maximum amount of information from these limited surviving elements.

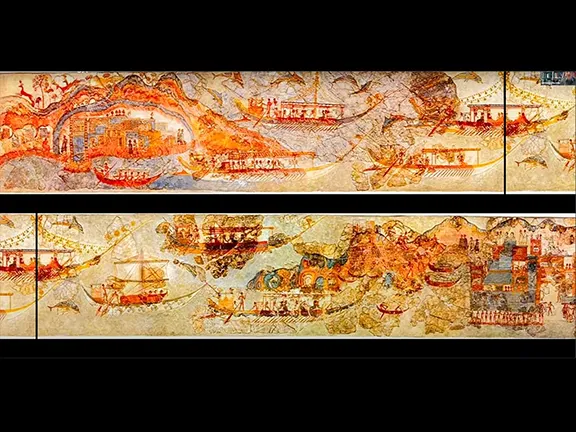

Mediterranean Ship Design in Bronze and Iron Age Art

Our understanding of shipbuilding during the Bronze and Iron Ages is frequently enhanced through comparative studies with other archaeological discoveries and the examination of iconographic evidence. Due to the scarcity of well-preserved hull remains from certain periods or regions, researchers often rely on comparing the available physical evidence with depictions of ships found in ancient art and with the findings from better-preserved shipwrecks dating to similar or later periods. By integrating these diverse lines of evidence, a more comprehensive reconstruction of ancient vessels and their construction techniques can be developed.

In the absence of extensive written records detailing seafaring practices and shipbuilding techniques from this distant past, archaeological evidence and artistic representations become invaluable sources of information. While the physical remains of Bronze Age and Iron Age ships, such as the Uluburun shipwreck, offer direct insights into construction methods and vessel capabilities, artistic depictions provide a complementary perspective. These visual representations, found across a variety of media, offer clues about ship types, their uses, and their symbolic significance within the societies that created them. By examining frescoes, pottery decorations, seals, and rock carvings, we can gain a deeper understanding of how ancient Mediterranean peoples perceived and interacted with the maritime world.

Mediterranean Ship Construction and Art during the Bronze and Iron Ages

The analysis will encompass various art forms produced by cultures such as the Cycladic, Minoan, Mycenaean, Egyptian, and Levantine, with a particular focus on identifying key features of the depicted vessels, their potential functions, and the cultural contexts in which they were created.

Alongside the analysis of ancient ships illustrated in Bronze Age art, where discernible from shipwrecks, the techniques used to construct ships around the time the art was created and within the same region will be examined in detail.

The aim is to synthesize the available evidence into a comprehensive overview of how ships were portrayed and built in the ancient Mediterranean during this formative era of maritime history.

Ship Models in the Mediterranean Bronze and Iron Ages

Ship models discovered across the Mediterranean region offer a tangible link to the ancient world's maritime endeavours. These miniature representations of watercraft, crafted from materials like clay and metal, provide invaluable archaeological evidence for understanding the evolution of shipbuilding, the nature of sea travel, and the cultural significance of maritime activities in the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. When the physical remains of actual vessels are scarce or deteriorated, these models can illuminate hull designs, construction techniques, and even the types of ships engaged in trade, warfare, or other forms of interaction. The study of these artifacts, therefore, is crucial for piecing together a comprehensive picture of Mediterranean maritime history, complementing evidence from shipwrecks, harbour installations, and artistic depictions.

Earliest Depictions of Masted Ships

The introduction of the sail marked a pivotal moment in Mediterranean naval architecture, fundamentally shifting the reliance on human-powered oared vessels. This innovation allowed ships to harness wind power for propulsion, enabling longer voyages, increased cargo capacity, and greater efficiency. Consequently, hull designs evolved to better accommodate masts, sails, and the resulting forces, leading to the development of more stable and seaworthy vessels capable of navigating larger distances and facilitating expanded trade, communication, and even warfare across the Mediterranean basin.

The sail appeared in different places at different times in artistic depictions in caves and rock shelters, on ceramics, in frescoes, on clay and metallic model ships.

The earliest depiction of a sailing ship is considered to be a representation of a boat with a bipod mast painted on pottery from the site of H3 as-Sabiyah in Kuwait dated to between 5300 and 4800 BC. This type of vessel was likely used in the northwestern corner of the Persian Gulf in the Mesopotamian Marshes.

In Egypt, representations of river boats with bipod masts are abundant from the Predynastic period and Old Kingdom, some datable to the 4th millennium BC (e.g., Qustul, Naqada III). Single masts were also used, with representations becoming less scarce later in the Old Kingdom.

By the end of the 3rd millennium BC, an Egyptian shipyard, Mersa/Wadi Gawasis, was building sea going vessels with a single mast and sails.

In the Aegean Sea, engraved boats with bipod masts in Asfendos Cave on Crete are considered Neolithic based on associated zoomorphs. Glyptic representations in Crete are reliably dated to the Middle Minoan I (c. 2000-1900 BC), while recent finds in Anatolia indicate sailing vessels in the Aegean by the mid-3rd millennium BC (c. 2500/2400-2200 BC). A graffito from Cufota might date to the mid-3rd millennium BC. Seals from Crete dated to between 2000 and 1800 BC, depict ships with masts.

In the central Mediterranean, at Tarxien, on Malta, engravings on a stele might provide evidence of sailing vessels in the central Mediterranean in the 4th millennium BC, although poor conservation makes interpretation difficult.

Physical evidence of masts and sails on shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea had to wait until the 2nd millennium BC and the discovery of ancient wrecks such as the Uluburun (1335 - 1305 BC). That is not to say that masts and sails were not used prior to then, only that the remains of any sails or rigging have been consumed by the sea.

So far, so good.

Until 2025 AD, it was considered that, geographically speaking, ship designs and ships architecture followed a tidy progression, developing in sophistication from Mesopotamia in the east, via Egypt, into the Mediterranean Sea and from the Aegean Sea to the western Mediterranean with some local pre-existing traditions providing variations on a theme.

Evidence of Independent Sailing Technology in the Western Mediterranean

In 2025 AD, a team of researchers from the University of Granada confirmed that prehistoric cave paintings at the Laja Alta site, in Jimena de la Frontera, are the oldest representations of sailing boats yet found in the western Mediterranean. Prior to then, the cave art was thought to date to the arrival of merchant traders from the east around 1000 BC, which neatly fitted in with the east to west scenario. The researchers argue that the depictions should be dated to the end of the 4th and 3rd millennium BC.

The question is, ‘Do the Laja Alta engravings depict a sailing technology that developed independently in the western Mediterranean?’

References

Aleydis Van de Moortel. (2017) A New Typology of Bronze Age Aegean Ships: developments in Aegean shipbuilding in their historical context' In book: J. Litwin (ed.), The Baltic and Beyond. Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Gdańsk, September 21-25, 2015 (Gdańsk) (pp.263-268)

Bass, G. F. (2005). Beneath the waters of time: The witnesses of history. University of Texas Press.

Broodbank, C. (2000). An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge University Press.

Casson, L. (1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cline, E. H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press.

Gillmer, T. C., & Johnson, B. (2002). Introduction to Naval Architecture. Naval Institute Press.

Haldane, C. (1993). Wooden Boats: Their History and Construction. W. W. Norton & Company.

Jouquand, F. (2011). Maritime Archaeology: A Reader of Submerged Cultural Heritage. Springer.

McGrail, S. (2001). Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. Oxford University Press.

Morgado-Rodríguez, Antonio, and Eduardo García Alfonso. “Embarcaciones Prehistóricas y Representaciones Rupestres. Nuevos Datos Del Abrigo De Laja Alta (Jimena De La Frontera, Cádiz.” Complutum 29.2 (2018): 239–265. Web.

Pulak, C. M. (1998). The Uluburun shipwreck: An overview. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 27(2), 147-184.

Sherratt, S. (2003). Trade, contact, and the movement of peoples in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age. In Sea routes...interconnections in the Mediterranean, 16th-6th c. BC (pp. 11-26). Istituto per gli studi micenei ed egeo-anatolici.

Tilley, C. (2007). An Archaeology of Materials: Substance and Sensibility. Berg Publishers.

Vlietinck, R. (2012). Ancient ship representations: A methodological approach. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology (ISBSA 12) (pp. 17-24). Oxbow Books.

Wachsmann, S. (1998). Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. Texas A&M University Press.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC  3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC

3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC 4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC

4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC 5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC

5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC 6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC

6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC 7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD

7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD