Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Shipbuilding during the Late Iron Age

Explore the long shipbuilding traditions of ancient Egypt and the Aegean, the rise of Hellenistic naval architecture, and the encounter with local boatbuilding techniques in the Western Mediterranean during the Late Iron Age. Learn about the development of biremes and triremes and the distinction between warships and merchant vessels.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-05-10 | Last Updated 2025-05-18 | Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 1,806 times

Replica of Hellenistic style trireme

Naval Architecture in the Mediterranean during the Late Iron Age

In Egypt, long established shipbuilding traditions prevailed, if occasionally influenced by Aegean innovations, whilst in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, naval architecture matured into a style known as Hellenistic. These ever more advanced vessels travelled west where they encountered local boat building techniques exemplified by the hand sewn boats of Zambratija Cove and the Romano-Liburnian shipbuilding tradition in the Adriatic and the sewn plank techniques employed along the Iberian coast, that had prevailed for hundreds and sometimes, thousands of years.

The Late Iron Age saw significant developments in warship design, leading to more specialized fighting vessels. The development of ships with two and then three banks of oars, biremes and triremes respectively, revolutionized naval power in the Mediterranean. This increased speed, manoeuvrability, and the number of rowers available to power the vessel and potentially act as fighting men. The ram became the primary weapon.

During this period, a clearer distinction emerged between dedicated warships and slower, rounder merchant vessels.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Late Iron Age Ship Depictions in the Eastern Mediterranean

Assyrian Reliefs

Assyrian reliefs dated to the 7th century BC show Phoenician warships with pointed rams and often a single level of oars.

Sennacherib's Palace

The most detailed representations of seagoing Phoenician ships come from the palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh.

A specific relief from Sennacherib's palace depicts the waterborne flight of the Tyrian king Luli to Cyprus, dating to c. 701 BCE. This relief shows two types of ships: sleek galleys (warships) and round merchantmen.

The reliefs feature warships with sharp-edged waterline rams and brailed sailing rigs and round ships whose rigging is not depicted.

Both ship types feature twin banks of oars and may be intended to represent ships as large as fifty-oared penteconters, though the figures are presented at a much larger scale than the ships, showing only nine to eleven rowers per side.

These Nineveh reliefs, dating to the late eighth/early seventh century, also illustrate the principal ramming timber used for earlier Archaic penteconters, which was sheathed with hammered plate-bronze and tapered to a point. The ram found on the Marsala wreck was similar to those depicted in Sennacherib's reliefs.

Late Iron Age Model Ships from Cyprus

Archaeological excavations at Amathus in Cyprus have yielded clay boat models dating to the sixth-century B.C. These models offer valuable insights into the types of watercraft used in Cyprus during this period. Two of the discovered models are identified as representations of merchant vessels, distinguished by their broad beams and deep hulls, indicating their capacity for carrying substantial cargo. The largest of these merchant vessel models features detailed elements such as strakes along the waterline, which would have held "under-girding" ropes used to strengthen the hull against the stresses of sea travel, as well as large catheads at the bows designed to accommodate anchors. The models also depict a helmsman seated in the stern, equipped with two steering oars, providing specific information about the steering mechanisms of these vessels.

An additional clay boat model from Amathus is characterized by the presence of a deck and a small deckhouse, suggesting another type of vessel used for different purposes, possibly for passengers or smaller-scale transport.

Late Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean

As we move into the Mediterranean Late Iron Age, the number of discovered shipwrecks increases exponentially. Furthermore, generally speaking, the remains of the hull are better preserved than in previous periods allowing us to analyse naval technology with more precision. Astute readers will realise there is a noticeable gap between the last Late Bronze Age open sea wrecks, the Gelidonya about 1200 BC, and the first Iron Age open sea wreck, Mazarron II that foundered in about 625 BC.

Late Iron Age Shipwrecks in Egypt

Pegged mortise and tenon joints

Thonis-Heracleion Baris type ships (664 – 332 BC)

Thonis-Heracleion served as a maritime gateway for ships travelling up the Nile. It was occupied as early as the late eighth or early seventh century BC, experiencing its "golden age" in the second century BC. In the Late Period (664–332 BC), the city controlled access to the Canopic branch of the Nile. It is described as 'The Gates of the Sea' and functioned as a customs station and emporium. It oversaw Greek ships in transit to Naucratis and Memphis and was engaged in trade with Greece. The city sank beneath the waters of the Nile delta during the 8th century AD and was rediscovered in the 1990s by a team of archaeologists led by Franck Goddio. Amongst the artifacts discovered at Thonis-Heracleion were sixty-four (to date – 2020) ancient Egyptian ships. Many of these ships seem to belong to the baris-type as described by Herodotus in his Historia.

The construction of the baris-type ships found at Thonis-Heracleion, particularly one recorded as Ship 17, reveals distinct features that differentiate them from sea-going vessels and highlight their suitability for river and fluvio-maritime navigation.

The baris was a flat-bottomed freighter with a crescent-shaped hull. These ships were constructed from local acacias. Unlike Ancient Egyptian sea-going vessels, which were built from imported wood, acacia had been used for river-faring boats since the Old Kingdom.

A central keel-plank or a kind of proto-keel was present, but it did not project beneath the hull. The proto-keel segments in Ship 17 were relatively short, not exceeding 3 m in length. This flat, non-protruding keel design was advantageous for river navigation and is comparable to the construction of modern nuggars on the Upper Nile.

The hull planking consisted of short planks, arranged like ‘courses of bricks.’ In Ship 17, the average length of the planks was only 192 cm.

The planks were joined using long tenons, some reaching up to 2 m. These tenons passed inside rectangular channels cut into the middle of the planks’ edges. Uniquely, the tenons were pegged to the planking at the extremities. This pegging was not typical for the planking of sea-going ships, which used free tenons to facilitate assembly and disassembly for transport. The tenons also served to wedge the through-beams to the planking.

The internal structure, including the beams, was characterised by strong asymmetry and roughness of execution. Beams were often not horizontal and were made from irregularly shaped branches. The inner joints between the planks were sealed with papyrus.

The vessels of this type studied so far from Heracleion were undecked, although Herodotus' description of baris used for trans-shipment might suggest some were decked. The absence of a deck could have facilitated rapid trans-shipment of cargo.

The baris was steered with an axial rudder that passed through an opening in the keel. This type of rudder is characteristic of Nilotic ships and generally not considered ideal for sea-going vessels.

The baris was a sailing ship. Evidence from Ship 17 suggests the mast was situated in the middle of the hull. While a ratio of mast height to hull length close to 2:3 was typical for Egyptian boats, achieving the estimated 17-18m mast height for Ship 17 from local acacia wood would have been impossible. This suggests the mast was likely shorter or made of different wood, with the shorter mast hypothesis being more convincing given the detail in Herodotus' descriptions. There were no traces of rowing arrangements found on these ships from Heracleion. If the ship could not overcome the current, the mast could be used to attach a tow line.

Baris were built with varying carrying capacities. Ship 17, one of the largest found, was about 27–28 m long with an 8 m beam, giving a length-to-width ratio of around 3:4. It had an estimated displacement of about 150 metric tonnes and a tonnage of approximately 112-113 metric tonnes. This resulted in a relatively shallow draft of about 1.6 m, which was advantageous for navigating the river and shallow lagoons.

The short plank segments presented challenges for the longitudinal strength of the crescent-shaped hull. It is not entirely clear how this was addressed, though a bulwark might have played a role in counterbalancing hogging, and through-beams hypothetically reinforced the structure.

Ship 17 showed no traces of shipworms on its exterior, suggesting it did not spend extended periods in saline water. Anchors of a marine type were used, as confirmed by Ship 43 which had a 100 kg anchor at the bow. While marine anchors were not typically used on the Nile (where wooden stakes hammered into the banks were common), their presence suggests either mooring beyond the sandbar, within the estuary/harbours, or a change in mooring techniques due to increased fluvio-maritime traffic. The environment of the coastal lagoon at Thonis-Heracleion, with its sedimentology and potentially high shipping density, likely favoured the use of marine-type anchors.

Overall, the construction features, such as the flat, non-protruding keel, short pegged planks, and axial rudder, strongly indicate that the baris of Thonis-Heracleion were a local type primarily adapted for river or fluvio-maritime use. Their shallow draft was well-suited to the conditions of the Delta and shallow lagoons. However, the construction features also suggest they were not particularly seaworthy or adapted for open sea conditions.

Mataria (c 500 BC) Egypt

The "Mataria boat" refers to the remains of an ancient Egyptian vessel discovered in 1987 during construction work near Heliopolis in El Mataria, a suburb of Cairo. While not a deep-sea shipwreck, it is a significant find for understanding ancient Egyptian shipbuilding and its potential connections to Mediterranean techniques.

The Mataria boat is dated to the Late Period, around 500 BC.

It was found approximately 10 metres deep in the sand, suggesting it was abandoned near an old Nile canal. Tragically, about one-third of the vessel was destroyed by heavy machinery during the construction before its significance was fully realized.

Based on reports from construction workers, the hull is estimated to have been about 11 metres long, 4 metres wide, and 1.2 metres deep. It reportedly had 15 planks on either side.

The Mataria boat is considered the first direct evidence of pegged mortise-and-tenon joints in an Egyptian hull. Earlier Egyptian shipbuilding primarily used lashed mortise-and-tenon joints. The use of pegs to secure the tenons represents a significant shift and shows a potential influence or interaction with Mediterranean shipbuilding traditions of the time. This technique was common in Greek shipbuilding.

The surviving portion showed the use of mortise-and-tenon joinery, with pegs used to fasten the tenons within the mortises. This is a departure from earlier Egyptian vessels where the planks were typically joined edge-to-edge and then secured with lashings.

While a significant portion was destroyed, the surviving remains of the hull itself are the primary artifact of importance. The construction techniques used are the key to its archaeological value. The context of its discovery near an old Nile canal suggests it was likely a riverine vessel.

Development of the Hellenistic Architectural System

Greek Bireme

The Late Iron Age saw the development of a type of naval architecture known as Hellenistic that reached maturity over the period 323 BC to 30 BC. This architectural system was significant because it allowed for the building of larger ships with elaborate hull shapes, capable of good nautical performance. This technical progress was a factor in the significant maritime expansion at the end of the first millennium BC. It was used for different types of vessels, including coasters, seagoing ships, and warships.

Key defining features of ships built in the Hellenistic fashion

A cross-section with a retour de galbord, i.e. a cross-section with a wine-glass profile.

An axial frame composed of a keel extended toward the extremities by the stem and sternpost; according to the ship’s importance, end pieces can be more or less numerous and form stem and stern complexes.

A rabbeted keel and a carved polygonal garboard.

Carvel planking assembled by mortise-and-tenon joints.

A framing system composed of alternating floor timbers and half frames faced on the keel axis; floor timbers and half frames are extended by futtocks fitted with butt joint; all the frames elements are nailed or tree-nailed to the planking; the floor timbers, with some exceptions, are independent of the keel.

Transverse beams supported by the wales of the planking.

An internal axial frame with a keelson/mast-step timber extended by a simple keelson; keelson and mast-step timber are fitted on the back of the floor timbers.

A longitudinal internal framing composed of stringers nailed to the frames and mobile ceiling planks.

A Hellenistic style ship may also have the following characteristics:

A longitudinal section which may include an important rake; the bow shape (convex, straight or concave) varies according to the vessel type.

The stem complex may include a cutwater, and the stern complex a heel located under the sternpost in the extension of the keel, and acting like a drift board.

The planking might be single- or double-covered with lead sheathing.

The development of the Hellenistic architectural system for ships can be broadly categorised into several phases, illustrated by various shipwrecks.

Early Greek Sewn Boats (Archaic Period)

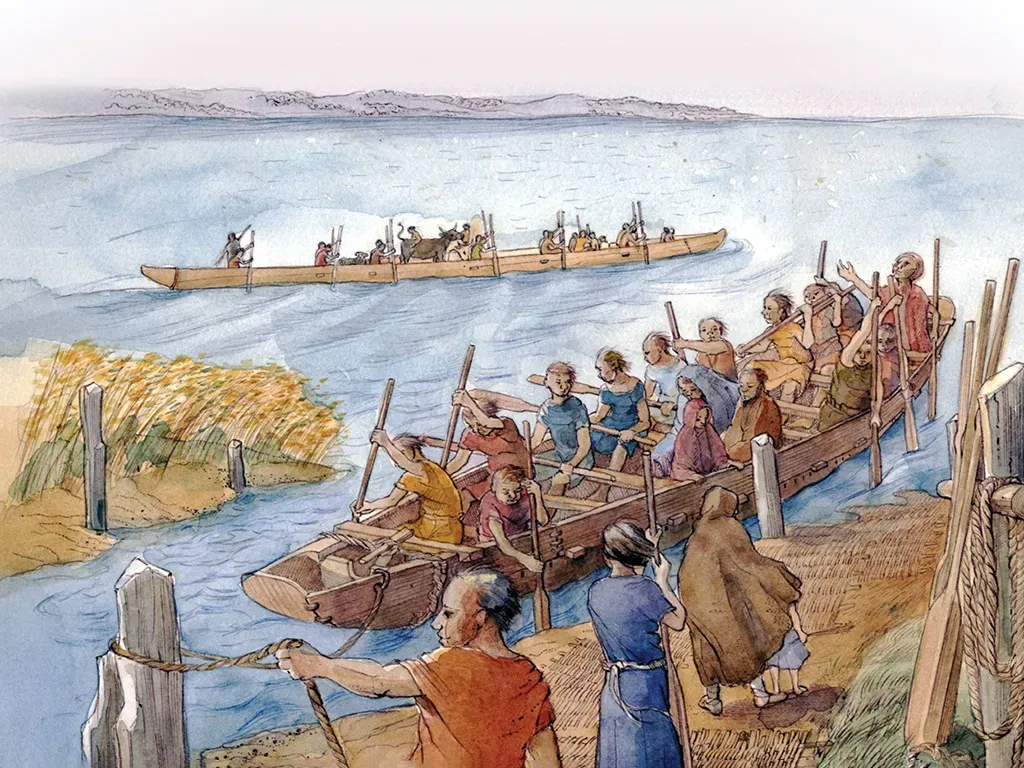

Gyptis at Sea

The early Greek sewn boat tradition, also referred to as the Greek Archaic sewn-boat tradition or its 'original phase', represents a distinct shipbuilding approach primarily evident during the 6th century BC. This tradition is widespread, found in both the western and eastern Mediterranean due to Greek colonization.

Key characteristics of the early Greek tradition

Sewn planking assembly: The hull planking is primarily assembled using ligatures (sewing).

Unique sewing technique: This tradition is particularly characterised by a specific sewing system involving tetrahedral recesses associated with the stitch-channels. These tetrahedral recesses are considered a distinct "technical signature" or "fingerprint" of this tradition.

Use of pre-assembly elements: The sophisticated nature of the sewing system involves elements like pre-assembly components. Pre-assembly components included the cylindrical dowels that were driven into the thickness of the plank edges and rectangular, unpegged tenons.

Lashed frames: Frames were often lashed to the planking.

Protective coating: A protective, watertight coating, such as beeswax and coniferous pitch, was applied to the inboard surfaces of the hull.

Vessel types: Wrecks belonging to this phase include both large ships (15–25m long) and smaller coastal boats (around 10m long).

This system developed over a long period, possibly originating as far back as the Bronze Age in the Aegean Sea.

The shipwrecks specifically linked to this early Greek Sewn boat tradition of the Archaic Period are those identified as belonging to the 'original phase', dating primarily to the 6th century BC are the Bon-Porté 1, Giglio, Jules-Verne 9, Pabuc Burnu, and Cala Sant Vicenc.

Bon Porte (c 550 BC) Southern France

The Bon-Porté 1 wreck was dated to the second half of the 6th century BC by its cargo of Etruscan and supposed Ionian amphoras. The wreck was discovered near Saint-Tropez (France).

Bon-Porté 1 was one of the first wrecks recognised as a Greek Archaic sewn boat.

Its construction is characterised by a specific sewn assembly system. This system includes the presence of tetrahedral recesses associated with stitch-channels, considered a "technical signature" or "fingerprint".

The planking was sewn, and the frames were lashed to the planking.

Due to a high degree of similarity in assembly techniques with the Jules-Verne 9 wreck, Bon-Porté 1 and Jules-Verne 9 can be considered "sister ships".

Giglio (c 580 BC) Tuscany

The Giglio wreck was found at a depth of 45 - 50 metres, on the seaward or western side, of a reef in Campese Bay which is on the western side of the island of Giglio. The island of Giglio lies 50 kilometres south of Elba and 15 kilometres from the mainland at the southern end of the Tuscan Archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Only a part of the Giglio wreck has been recovered, the after end of the keel and some planking. Nine different species of wood have been identified as being used in the construction of the ship; pine, fir, box, oak, holm oak, elm, olive, hazel, and Phillyrea.

The ship was constructed shell first and laced. The style of lacing is unusual, having been identified on only two other ancient shipwrecks, the Bon Porte ship that sank about 550 BC and the Gela ship that sank about 500 BC.

This lacing technique used on these three ships involves the following steps:

Notching: Cut triangular notches along the inner edges of the planks.

Drilling: Drill diagonally through each plank, starting from the notch. Instead of exiting the plank on the outer side, the hole should emerge at the seam where the planks meet.

Lacing: A matching notch and drill hole are created on the adjacent plank. Cord is threaded back and forth through the matching holes in the two planks. The cord is pulled tight to secure the planks together. Each hole is then plugged with a small wooden dowel.

Reinforcement: Wooden pins (treenails) are inserted horizontally across the seams to provide extra strength and support.

Waterproofing: Pine pitch (resin) is used to seal the seams and prevent water leakage.

Jules-Verne 9 (c 570-560 BC) Marseilles

The Jules Verne 9 shipwreck is dated to the late 6th century BC, approximately 570-560 BC, based on the archaeological context and associated finds. This places it within the early Greek colonial period of Massalia (Marseilles).

The Jules Verne 9 was a fully sewn boat. This means that all the structural elements, including the hull planks and frames, were assembled using ligatures (strong cords or ropes) made from plant fibres.

The remains of the stitches found on the wreck allowed researchers to precisely reproduce the lashing system, which was particularly sophisticated.

The hull planks were placed edge-to-edge. To prevent movement between them, they were carved with notches or "joggles." The planks were then secured to each other using plant fibre lashings that passed through diagonal channels cut into the plank edges and exited via pyramidal (tetrahedral) recesses on the inboard face of the planks. Incised lines were found on the hull planks, likely indicating the locations for sewing holes to ensure proper spacing during construction.

The frames (ribs) and deck beams, which provided rigidity to the long and narrow hull, were also attached to the planking using the same lashing technique. The frames were widely spaced.

Top timbers with rectangular sections were inserted along the upper sides of the hull.

The vessel was built using the shell-first method. This means the hull planks were assembled and joined together to create the shape of the hull before the frames were inserted and attached.

The outer surface of the ship's sheathing board was coated with realgar mixed with wax and pine resin to make it watertight.

Replica Jules Verne 9 – Gyptis

In 2013 AD, a full-scale working replica of the Jules Verne 9, named Gyptis, was built. This reconstruction allowed researchers to investigate the assembly process, functionality, and maintenance aspects of this construction method. The Gyptis project demonstrated the nautical capabilities of such vessels.

The Gyptis was built using materials and techniques as close as possible to those that would have been used in the 6th century BC. This involved assembling the hull planks edge-to-edge and sewing them together before inserting the frames. The boat was made watertight using a coating of wax and resin.

The Jules Verne 9 was a relatively small vessel, estimated to be around 9.85 metres in length and 1.88 metres in width. The Gyptis replica would share these dimensions. It was designed as a light and fast coastal vessel, likely used for fishing and short-distance transport.

The Gyptis is propelled by oars and a square sail of about 25 square metres. It is steered using quarter rudders (oars at the stern).

The construction of the Gyptis was a significant project in experimental archaeology. The aim was to understand the shipbuilding techniques of the time, the boat's performance, and its suitability for coastal navigation.

Sea trials of the Gyptis subsequently demonstrated that it was a light and fast sailer, providing valuable insights into the capabilities of such ancient vessels.

Pabuc Burnu shipwreck 6th c BC (Turkey)

The 6th-century BC Pabuc Burnu shipwreck was discovered off the coast of Turkey near Bodrum. Excavations by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) in 2002 and 2003 revealed scant but crucial remains of the hull.

The Pabuc Burnu ship provides the earliest archaeological evidence for laced shipbuilding in the Aegean.

The hull planks were placed edge-to-edge and held together by coaks inserted between the strakes. Notably, the Pabuc Burnu ship used tenons as coaks, the earliest known instance of tenon usage in Greek shipbuilding. Other contemporary shipwrecks from the Western Mediterranean used dowels as coaks.

Ligatures, made from fibrous plants, were then laced through oblique holes drilled through characteristic tetrahedral notches along the edges of the planks. After lacing, alder pegs were hammered into the holes to secure the ligatures and create a watertight seal.

The ship had widely spaced, manufactured frames. These frames had trapezoidal sections and were notched over the planking seams on their underside. The frames were then lashed to the hull. Top timbers with rectangular sections were inserted along the upper sides of the hull and were attached to the planking by both lashing and treenails (wooden dowels).

Two repair planks found on the hull were attached using a combination of lacing and dowels/coaks inserted through diagonal holes, indicating repair techniques of the time.

The employment of tenons as coaks marks an early step towards the later widespread adoption of mortise-and-tenon joinery. The presence of both lacing and early forms of tenon joinery suggests that the mortise-and-tenon technique might have developed within the Greek tradition of laced construction, rather than being solely adopted from Phoenician or other shipbuilding practices.

Cala Sant Vicenc 533 – 501 BC (Majorca)

The Cala Sant Vicenc wreck was excavated in 2002–2004 on Majorca in the Balearic Islands. Based on its cargo, the boat is likely of Massalian origin and dated to the last third of the 6th century BC.

The wreck presents a sewn system of assembly and the presence of tetrahedral recesses.

The frames found on the Cala Sant Vicenc wreck are lashed to the planking. This lashing system is similar to those found on the Jules-Verne 9 wreck.

The wreck was constructed using pre-assembly unpegged tenons and cylindrical dowels. These unpegged tenons and cylindrical dowels seem to have been used like coaks, serving to guide and hold the planks in place prior to sewing. More specifically, on the Cala Sant Vicenc wreck, dowels were used to fit the garboard to the keel, which also corresponds to a repair. Unpegged tenons were used for the pre-assembly of the rest of the planking.

The combination of unpegged tenons and cylindrical dowels is associated with major repairs on this wreck. The rectangular unpegged tenons used do not appear to be a formal step in the development of shipbuilding techniques and may represent a variant or a fingerprint of a particular shipyard.

First Transitionary Phase (Late Archaic/Early Classical)

Dowels and lashings (as on Cala Sant Vicenc)

The first transitionary phase of the Greek shipbuilding tradition is specifically linked to several shipwrecks that demonstrate a shift away from exclusively sewn planking assembly towards the increasing use of mortise-and-tenon joints, while still retaining elements of the older techniques. This phase is dated to the late Archaic and early Classical periods, specifically from the end of the 6th century BC to the second half of the 4th century BC. The hull shapes in this phase were still round. Examples of shipwrecks from this period include Jules-Verne 7, Villeneuve-Bargemon 1 (aka Cesar 1), Grand Ribaud F, and Gela 1.

Jules-Verne 7 (c 525-510 BC) Marseilles

Jules-Verne 7 was found in Marseilles, France. It had been abandoned towards the end of the 6th century BC. It is characterised by a mixed system of assembly employing mortise-and-tenon, sewing, and nail fasteners. The sewing is similar to the characteristic Greek system with tetrahedral recesses, and the hull structure and component morphology are identical to the earlier Jules-Verne 9. Floor-timbers were fastened with iron nails, and top frames were treenailed and lashed at the foot to the hull planking. Planking was mainly assembled with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints, but sewing was used on keel extremities, endposts, and for repairs. Its characteristics are considered Late Archaic.

Villeneuve-Bargemon 1 (aka Cesar 1) (c 510-500 BC) Marseilles

The César 1 wreck, also known as Villeneuve-Bargemon 1, discovered in Marseilles and dating to the 6th century BC, provides further valuable evidence for Archaic Greek shipbuilding practices in the Western Mediterranean. Its construction shares similarities with other contemporary wrecks like Jules Verne 9 and Pabuc Burnu but also exhibits some unique characteristics.

Like Jules Verne 9, César 1 was primarily constructed using the sewn-plank method. Hull planks were joined edge-to-edge and held together by lashings made of plant fibres. The lashings passed through diagonal channels cut into the edges of the planks, exiting on the interior face through tetrahedral or ogival notches. This is a characteristic feature of sewn boats from this period. The hull planks were carefully fitted edge-to-edge to create a tight seam before being lashed together.

The wreck preserved evidence of widely spaced U-shaped frames. These frames were inserted after the hull was planked (shell-first construction) and were attached to the hull planks using lashings.

Remains of top-timbers were also found, contributing to the vessel's structural integrity along the upper part of the hull.

Evidence suggests that organic material, likely moss or similar fibres, was used as caulking between the planks to improve watertightness. This would have been compressed by the tension of the lashings.

Unlike some later Greek and Roman ships, César 1 did not employ the developed mortise-and-tenon joinery extensively along the plank seams. The primary method of hull plank connection was lashing. This reinforces its dating to the earlier part of the Late Archaic period before the widespread adoption of sophisticated mortise-and-tenon techniques in this region.

Grand Ribaud F (500 – 475 BC) Southern France

The Grand Ribaud F was found off the Grand-Ribaud islet in the Hyères Archipelago, France, twenty kilometres southeast of Toulon.

The Grand-Ribaud F wreck is dated to the early 5th century BC by its cargo. It belongs to a "transition phase" in Greek shipbuilding, specifically the first transitionary phase, corresponding to the introduction of mortise-and-tenon joints within the Greek tradition of assembly by ligatures. This transition phase is generally described as lasting from the second half of the 6th century BC to the second half of the 4th century BC.

Despite its cargo of Etruscan amphoras, the observed hull components (planking, frames, sternpost, keelson, etc.) present the same characteristics as the Jules-Verne 7 shipwreck.

It is estimated to have had a likely length of 25m, making it much larger than Jules-Verne 7.

As part of the first transitionary phase, it illustrates the emergence of assembly systems using tenon-and-mortise joints for the planking and nailing for the frames.

Based on the characteristics shared with Jules-Verne 7, the construction included:

Planking mainly assembled with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints. The pattern of pegged tenons was not very closely spaced.

Floor-timbers were fastened with iron nails.

Top frames were treenailed and lashed at the foot to the hull-planking.

Sewing was used only on keel extremities, endposts, and for repairs. The repairs were made by sewing, not with tenons.

Gela 1 (c 500-480 BC) Sicily

Gela 1 was found off the southern coast of Sicily, near the Greek settlement of Gela. It is dated to the beginning of the 5th century BC and likely originated from the Aegean area. While belonging to the first transitionary phase, Gela 1 is noted as possibly being an intermediate or specific step within the group, where sewing is still dominant but with some variants, and mortise-and-tenon joints seem to be used only at the ends and in addition to sewing. Pegged tenons alternate with cylindrical dowels.

Detailed construction details of Gela 1

This ship is described as being of a ‘shell’ type. The primary bearing structure was the planking. The hull was formed from boards of various widths that were connected with plant fibre cords. This "sewn plank" technique was long-tested and common in the Aegean, with examples dating back as early as the third millennium B.C.

The planks were sewn together using plant-fibre cords passed through holes drilled obliquely along the interior edge of the planks. Cylindrical wooden dowels, set horizontally at intervals of 18 centimetres in the seams, were inserted prior to sewing to increase the connection between planks. Triangular notches, created using a gimlet or gouge, also helped introduce the cord. This method resulted in a solid hull.

The builders also used cylindrical treenails and mortise-and-tenon joints in the stern area to further improve the hold. The combination of sewing planks and the mortise-and-tenon technique is documented in other wrecks of the period such as Mazarron 1 and 2, Jules Verne 7 and the Ma’agan Mikhael.

Fabric was inserted along the seams on the interior of the hull to prevent water seepage, and the inner surface was sealed with pitch for impermeability. This system is also documented in ancient texts such as the Homeric poems and found in numerous other wrecks like the Mazarron 1 and 2, Jules Verne 7, the Giglio, the Bon Porte and the Kyrenia.

Fragments of lead plates found may have protected the exterior hull and prevented mollusc attachment.

Floor timbers, 17 in total, were laid across the vessel but did not have a bearing function, acting more as a thickening of the hull. Sixteen of these passed under the keelson. Additional pieces of wood beneath the floor timbers in the central portion helped maintain a constant height.

Four strakes (planks) made from light pine boards were preserved and fixed to the bearing structure, while others were separated. Strakes at the centre of the vessel were preserved in situ and still bound together with plant fibre cords.

Triangular notches called ‘limbers’ were present at the centre and base of each floor timber and above the keel to allow bilge water and rainwater to flow freely.

The external keel was also connected by sewing and had a rabbet for placing the first plank (garboard strake). Its thickness was reinforced by the keelson.

The keelson ran lengthwise along the entire vessel and was made from pinewood. It was laid with a system of fixed joints together with the mast-step. It had recesses and protruding elements for attaching supports for the overlying structure.

The mast-step was a notable element in the central and forward portions, made from two pieces of wood set side-by-side. It had recesses for the main mast and supporting elements.

The sternpost was identified, held with a fixed joint at the curving part, forming the end of the keel. It had rabbets corresponding to the ends of the hull planks.

A woven plant-fibre matting was found on the bottom of the ship, likely used for placing cargo on the wooden base.

Analysis of wooden remains identified pine (Pinus pinea) for floor timbers, keelson, keel, and a beam. Willow (Salix sp.) was identified in one fragment, thought to be from a non-structural object. The use of pine suggests a lighter rather than a harder, more resistant boat.

Dimensions of Gela 1

Gela 1 measures 18.00 x 6.80 metres. Its total length is estimated to be 17 metres, a large ship for the period.

Floor timbers average 10 to 14 centimetres in height, and their straight portion measures four metres.

Floor timbers were kept at a constant height of 30 centimetres by additional wood pieces.

Wooden dowels were set at intervals of 18 centimetres in the seams between planks. Triangular notches were 15 millimetres on each side.

The external keel measures 0.25 x 0.37 metres.

The mast-step is 0.58 metres wide, 6 metres long, and 0.20 metres thick. The two pieces forming it were approximately 225 cm x 20 cm x 22 cm and 185 cm x 15 cm x 22 cm high.

Second Phase (Later Classical)

In this stage of development, exemplified by shipwrecks like Gela 2 and Ma’agan Mikhael, the use of sewing becomes even less common in favour of the further development of the tenon-and-mortise joint. Hull shapes begin to evolve, with the hull bottom starting to present a wine-glass cross-section, differing from the previously round shape. The mast-step timber continued to be directly fitted on the back of the floor timbers.

Gela 2 (c 450-425 BC) Sicily

The Gela 2 wreck, dated to around 450 - 425 BC, was found near the ancient city of Gela, Sicily, off the coast near Bulala. The discovery was made in 1988 by two scuba divers. The wreck lies in relatively shallow waters, around 6 metres deep, and about 300 metres from the shore.

This wreck displays characteristics of both the mortise-and-tenon technique and the sewing technique.

Construction details of Gela 2

The planking in the central portion of the hull is assembled by mortise-and-tenon joints, fixed with vertical wooden pegs set at regular intervals of about 20 cm. This type of spacing is considered characteristic of early examples of mortise joining.

A small tract of planking was held together not only with mortise joints but also with sewing, featuring the typical triangular recesses and remains of rope. This sewn section might represent a repair. The use of two different techniques in the same ship is noted in other wrecks, specifically, Mazarrons I and II, Jules Verne 7 and the Ma’agan Mikhael.

The ship rested flat on the bottom. The keel was likely torn off upon impact. A wooden element found (possibly a false keel) consisted of two pieces joined by mortise-and-tenon joints but lacked rabbets for plank assembly. It was excessively thick for a false keel compared to other wrecks such as the Kyrenia and Ma’agan Mikhael.

A keelson has not been recovered, and the observed structure doesn't clearly indicate its presence or form. A wooden block with a recess for superstructure struts, similar to one found on Gela 1, suggests a possible approach to keelson construction.

The skeleton of the ship had a wide frame space (60-70 cm). All floor timbers were complete with futtocks.

Floor timbers had a trapezoidal section with a rounded upper side. They were crossed by eight limbers. Floor timbers and futtocks were joined with hook timber scarf. Bronze nails with a square section held the floor timbers, futtocks, and planking together.

Along the deepest longitudinal axis, the floor timbers reached a height of about 0.5 metres, achieved by inserting two wooden planks below them, fixed with horizontal pegs.

Metal sheets (possibly lead) were found on the interior of the planking, fixed with small nails, and are thought to be internal reinforcement, perhaps from a repair.

A wooden palette, likely used to clean the limbers, was found still in position.

Wood analysis identified maple wood for the strut, holm-oak for the beam, tenon, and other fragments, and black pine for the planking.

The double curved bottom is seen as belonging to an advanced state of evolution in ship construction.

The co-existence of the two main techniques (mortise-and-tenon and sewing) in this wreck, located close to Gela 1, built primarily by sewing, highlights that geographical and cultural factors, not just chronology, influenced construction methods.

The wide frame space was 60-70 cm. Floor timbers reached a height of about one-half metre along the deepest axis. Planking strakes are between 25 and 30 cm wide and 4.5 cm thick where measurable. Vertical wooden pegs were set at intervals of about 20 cm. The third floor timber brought to light was preserved for 3.80 metres. The wooden block found had a recess measuring 13 x 5 cm. The wooden palette for cleaning limbers had a central circular section with a diameter of 7 cm.

Based on the length of the floor timber investigated, the dimensions of Gela 2 were probably not much different from those of Gela 1, which is estimated to be 17 metres long.

Ma'agan Mikhael shipwreck (c 400 BC) Israel

The Maʻagan Mikhael B shipwreck was found about 70 metres off the shoreline of Kibbutz Maʻagan Mikhael, which is located 35 km south of Haifa, Israel.

The Ma’agan Mikhael wreck is identified as representing the second phase in the development of the Hellenistic architectural type of shipbuilding.

Construction details of the Ma’agan Mikhael wreck

Reduced use of sewing. While sewing was still used to some extent in the first transitionary phase, it becomes even less common in this second phase. The frames were nailed to the planking with clenched copper nails.

Further development and increased use of the tenon-and-mortise joint for plank assembly.

Evolving hull shapes, with the hull bottom, which was previously round, starting to present a wine-glass cross-section.

The mast-step timber was fitted directly on the back of the floor timbers. This feature is consistent with earlier Greek sewn boats and the later Kyrenia wreck, the latter being considered the prototype for the fully developed Hellenistic type.

The floor-timbers, dating slightly later than Gela 2, were squarer with less slanted sides and a smooth base with only central limber holes.

The Maʻagan Mikhael ship is estimated to be 13.90 metres long.

This second phase, as exemplified by Ma’agan Mikhael and Gela 2, shows a progression towards the characteristics of the fully developed Hellenistic type, where sewing largely disappears (except perhaps in repairs or reused planks), the wine-glass cross-section is fully established, and frames become rectangular and nailed to the planking, unlike the earlier methods.

Fully Developed Hellenistic Type (Early Hellenistic)

The Kyrenia wreck, dated to the beginning of the third century BC (with construction possibly earlier, c. 325–315 BC), is considered the first known example and the prototype of this fully developed Hellenistic type. In this stage, seams and ligatures have largely disappeared (except possibly in reused planks). The hull cross-section is now a wine-glass shape, and the keel is completely rabbeted. Frames are rectangular and nailed to the planking, with half frames extending to the hull bottom. The mast-step timber is fitted on the back of the floor timbers. The Madrague de Giens wreck, though later (75 – 60 BC), is also presented as an excellent example illustrating the high degree of sophistication attained by this type and the design’s longevity of service.

Kyrenia (c 325 – 315 BC) Cyprus

The Kyrenia was a coastal freighter found at a depth of 33 metres, approximately a nautical mile Northeast of the harbour of Kyrenia on the north coast of Cyprus. The Kyrenia wreck is identified as the first known example of the Hellenistic architectural type (to date – 2025 AD). It represents the prototype of this system and the last stage of development in the evolution from earlier Greek sewn boats.

The wreck itself is dated to the beginning of the third century BC, around 295–285 BC. However, evidence of repairs on the shell suggests the boat enjoyed many seaworthy years before sinking, leading to a hypothesis that its construction dates back to approximately 325–315 BC.

Like other Hellenistic vessels, it conforms to a tripartite structure composed of an axial frame, planking, and transverse framing.

Everything indicates the ship was entirely conceived and realised using a ‘shell first’ method. This aligns with the principle of longitudinal and ‘shell’ construction for the Hellenistic type.

The hull cross-section is described as being a wine-glass shape at the end stage of development represented by the Kyrenia wreck.

The keel is described as being completely rabbeted.

It has carvel planking assembled primarily by mortise-and-tenon joints. By this stage of development, seams and ligatures (sewing) had totally disappeared, except possibly in some reused planks.

The framing system consists of alternating floor timbers and half frames. Frames are rectangular and nailed to the planking. The attachment method involved clenched nails driven into wooden dowels. The top timbers, previously located only at the top, are extended to the hull bottom to form half frames faced on the keel axis. The floor timbers are independent of the keel, with some exceptions not detailed for the Kyrenia wreck itself but noted as a general feature of the type.

The mast-step timber is directly fitted on the back of the floor timbers.

The hull was covered with lead sheathing, which was set in afterwards. This sheathing served to strengthen the hull and complete its waterproofing. It is noted as the first known example of this type of protection.

The wreck shows evidence of a number of repairs, indicating it was used for many years.

Iberian tradition with Punic influence

Mazarron II - Iberian tradition with Punic influence

The Iberian tradition with Punic influence is a distinct sewn-boat tradition, or at least one that incorporated ligatures in ship construction, found in Iberia during the Archaic and pre-Roman periods. This tradition has been defined based on particular shipwrecks.

The Mazarron 1 and 2 wrecks found near Cartagena (Murcia, Spain). These are considered the earliest examples in this group. They were initially dated to the second half of the 7th century BC but are now dated to the end of the 7th or the beginning of the 6th century BC (625–570 BC) based on an amphora found on Mazarron 2.

Binisafuller was found on Menorca in the Balearic Islands. It is dated to the 4th century BC.

Golo is located in Corsica. It is dated to the Archaic period.

Initially, the Mazarron wrecks were identified as Punic ships. However, due to their local origin and the tradition's longevity until at least the 4th century BC, it has been re-evaluated as an Iberian shipbuilding tradition influenced by Punic contacts and colonization. This influence is likely a result of the presence of Punic settlements in southern Iberia. The societies in the region had undergone significant cultural blending with the Phoenicians over centuries, making it challenging to pinpoint origins. These boats probably served local transportation needs within a broader commercial network overseen by the Phoenician colonial elites and ultimately connected to the Tyre state.

The use of mortise-and-tenon joints in planking, found as early as the Archaic period in these wrecks, reveals an obvious Punic-Phoenician influence. Pegged mortise-and-tenon fasteners feasibly originated on the Levantine coast in a Canaanite or proto-Phoenician context, evidenced by earlier wrecks like Uluburun and Cape Gelidonya. The Roman writer Cato the Elder even referred to mortise-and-tenon joints as 'coagmenta punicana' or 'punic joints', highlighting their Punic-Phoenician origin.

An interesting study of the fibres used for the stitching on Mazarron I supports the theory that the boat was built locally in the Iberian Peninsula.

The ship's stitching was made from esparto grass (Stipa tenacissima L.), a plant endemic to the southeastern Iberian Peninsula (around Cartagena, Spain) and the northwest of Africa. This indicates the use of local materials and potentially a local shipbuilding tradition.

Mazarron II (625 – 570 BC) Murcia

Mazarron II is a coastal trading vessel that sank during the Phoenician period off the coast of Mercia in southern Spain about 600 BC and is the most complete ancient shipwreck found to date. Almost all the vessel, from bow to stern is preserved.

Mazarron II is 8.10 metres in length and its maximum beam is 2.25 metres. It was constructed by first laying the keel with a keelson on top. Both were made of wood from the cypress tree. The keelson has mortises for securing the mast. Next the strakes, or planks, were added to form the hull. These were made from pine wood and fastened using dowels with plant fibres to caulk the seams. The frames are constructed from the wood of the fig tree.

A method of construction called carvel build was used. The planks are fitted edge to edge and secured using mortise and tenon joints with olive tree wood pegs driven through the joint to secure it. This method of construction was used in a minor way on the 14th century BC Uluburun wreck and obviously developed in the intervening 700 years. Previous methods involved sewing the strakes together.

At the eighth row of strakes supports for seven beams were attached. Beams give the boat more rigidity. There also appear to be fittings for five thwarts. Finally, the fig tree wood frames were inserted inside the hull and attached with esparto cord sewn through the strakes. The Phoenician influenced boat builder of this period could not quite escape from the traditional sewn joint methods. The whole of the inside of the hull was given a good coat of resin to make it water-resistant. Mazarron II is the best-preserved example of such a boat from this period.

The anchor was found intact near the starboard bow of the vessel. It is made of wood and lead. It has two palms, and a wooden shank with a wooden stock filled with lead. A ring attached the anchor to esparto rope. This is the earliest true anchor to be found. All other previous anchors found were simply large stones pierced by a hole for attaching the anchor cable.

Mazarron I (c 600 BC) Murcia

Mazarron I is a coastal trading vessel that sank off the coast of Murcia in southern Spain about 600 BC during the Phoenician period.

The remains of Mazarron I only include a nearly complete keel made of cypress, nine partial planking strakes and four fragmented fig tree frames.

From these few remains certain deductions have been made. Mazarron I was about 8.2 metres overall with a beam of 2.2 metres.

The stem was fixed to the keel using a ‘T’ shaped scarf joint designed to withstand vertical as well as horizontal stress. The method of fastening the strakes used on Mazarron I was a combination of two established methods, tightly pegged or dowelled mortise and tenon joints together with sewn seams. Esparto grass yarn was used for the stitching. The hull, inside and out, was coated with pine tar to preserve the wood and provide another level of waterproofing.

Golo shipwreck 600 – 500 BC Corsica

The Golo shipwreck was found in Corsica, at Mariana, Haute-Corse, at the mouth of the Golo river near Bastia.

It has been suggested that the Golo wreck should be dated to the 6th century BC, placing it within the Archaic period.

Although the method of fastening the frames was not precisely observed due to the age of the discovery, several clues, such as the absence of any nail or treenail and the remains of cords, strongly suggest that the cylindrical frames were lashed to the planking, similar to the method found on Mazarron 1 and 2.

The Golo shipwreck is considered part of the Iberian tradition with Punic influence. This classification emerged from the re-evaluation of the Golo wreck, considering new data from the Binisafuller wreck and contrasting it with earlier interpretations that proposed a Phoenician origin.

The reasons for classifying Golo within this tradition are primarily based on shared architectural characteristics with other wrecks from the Iberian coast, Mazarron 1 and 2 and Binisafuller. The Golo wreck, dated to the 6th century BC, exhibits several key features.

The Golo vessel, which was preserved in its entirety and measured more than 14m long, has a similar longitudinal profile and round transversal section with a keel, to that of Mazarron 2. It also featured cylindrical frames and a similar implantation of the mast-step timber.

The planking was assembled using a pattern of mortise-and-tenon fasteners.

Although not precisely observed due to the age of the discovery, clues such as the absence of nails or treenails and remains of cords strongly suggest that the cylindrical frames were lashed to the planking, similar to the method found on Mazarron 1 and 2. This combination of planking assembly and frame fastening is a defining characteristic of this group of wrecks.

The continued use of lashings for frames in a period when nailing or treenailing was becoming common in Mediterranean shipbuilding is a strong indication of a local Indigenous tradition. The lashing of frames on Golo, Mazarron, and Binisafuller is seen as evidence of an earlier local tradition of Iberian origin before the widespread adoption of mortise-and-tenon fasteners. Thus, the Golo wreck is considered to represent this Iberian tradition that adopted mortise-and-tenon planking as a result of contact and colonization by Punic groups.

Binisafuller shipwreck (c 375 – 350 BC) Minorca

The Binisafuller wreck was found in Minorca in the Balearic Islands. It was discovered in the 1960s, first excavated in 1975, and again in 2006–2007.

Its cargo of Iberian amphoras from the region of Valencia dates it to 375–350 BC.

The Binisafuller wreck shares characteristics with the Iberian tradition with Punic influence.

The planking was assembled using mortise-and-tenon joints. The pattern of these joints is described as more sophisticated than that seen on the earlier Mazarron and Golo wrecks.

All the frames were lashed to the planking. The lashing system was similar to that used on Mazarron 1 and 2, but with some refinements.

Unlike the cylindrical frames found on some earlier wrecks in this group (like Mazarron and Golo), the frames on Binisafuller had a round back and a narrow foot. This design, described as "trapezoidal" in contrast to cylindrical, allowed for stronger lashing.

The lashings passed through holes in the planking that were slightly angled. Importantly, pegs locking the stitches were observed. On the outboard (exterior) surface of the planking, a groove linked the pairs of holes used for the lashings. This groove was filled with pitch, serving to lodge and protect the lashing cord.

A protective coating covered the inside of the hull. The mention of pitch filling the outboard grooves suggests a protective/waterproofing coating was also applied externally.

Overall, the Binisafuller wreck exemplifies the key characteristics of the Iberian tradition with Punic influence – the combination of mortise-and-tenon planking and lashed frames. However, it shows developments compared to earlier examples like Mazarron and Golo, with a more sophisticated mortise-and-tenon pattern, specific frame morphology better adapted for lashing, and the use of pegs and protected outboard grooves for the lashings.

Ancient Shipyards at Zea

Olympias at sea

It may seem obvious, but ships have to be built somewhere. Smaller, coastal vessels such as the Mazarron ships, would have been built at the many small coastal settlements and sheltered coves that dotted the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Larger vessels required special facilities such as slipways and boat building sheds. Examining ancient slipways and shipsheds can tell us a lot about the shipbuilding techniques employed at the time and the size of the boats that were being built.

We have already identified shipbuilding facilities in Egypt as early as 2040 BC (see Middle Bronze Age Maritime Technology) and an Iron Age shipyard on Dana Island off the southern coast of Turkey (see Early Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean Sea).

The Phoenician cities of Tyre, Sidon and Byblos, and colonies, such as the Punic city of Carthage and the Phoenician city of Cadiz would, in all probability, have had shipyards and sheds.

In the Greek sphere, Delos in the Cyclades had a significant harbour and recent underwater archaeological work has revealed ancient coastal structures and a port. Still within the Greek sphere, archaeological investigations on the island of Aegina in the Saronic islands have revealed the presence of ancient shipsheds dating back to the Classical period.

The most extensively researched ship building facilities are in Greece, in Piraeus, the harbour area and suburb of Athens.

The ancient slipways at Zea, located in the Bay of Zea (modern-day Pashalimani) in Piraeus, Greece, were a crucial part of the ancient Athenian naval base.

Zea was the largest of the three ancient harbours of Piraeus (the others being Mounichia and Kantharos) and served as the primary base for the Athenian fleet, particularly the triremes, the powerful warships that were the backbone of Athenian power.

During the Classical period (roughly 5th to 4th centuries BC), Athens rose to prominence largely due to its naval strength. The slipways and shipsheds at Zea were essential for maintaining this fleet, which played a vital role in major historical events like the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War. An ancient writer even noted that Athens' naval base was considered more impressive than the Acropolis.

The naval installations at Zea in the 4th century BC were among the largest building complexes of antiquity, demonstrating Athens' commitment to projecting its naval power. By the late 330s BC, the shipsheds at Zea alone covered an area of over 55,000 square meters.

Extensive archaeological investigations, known as the Zea Harbour Project (ZHP), have been conducted since 2001, significantly enhancing our understanding of these ancient structures.

The ZHP has identified at least four construction phases at Zea.

Phase 1 (Early 5th century BC): Unroofed slipways designed for hauling and slipping ships. These are the earliest identified naval installations in the Piraeus. It's believed they were eventually deemed impractical due to a lack of protection for the warships.

Phase 2 (Later 5th century BC): These slipways were built over with monumental shipsheds. These structures consisted of parallel stone colonnades supporting roofs, offering much better protection for the vessels and prolonging their lifespan. These Phase 2 shipsheds and the earlier Phase 1 slipways represent the only solid archaeological evidence of the 5th-century BC Piraean naval bases, a period of Athenian naval dominance in the Aegean.

Phase 3 (375-350 BC): Previously documented shipsheds were re-evaluated and identified as double unit shipsheds, capable of housing two ships end-to-end.

The shipsheds were long, parallel, roofed structures with stone and timber ramps sloping up from the water. The roofs, made of tile and supported by hundreds of columns and walls, provided protection from the elements, allowing for maintenance and storage of the triremes. Their length ensured that entire ships could be drawn out of the water.

By the late 4th century BC, the harbours of Zea, Mounichia, and Kantharos together could house an estimated 372 triremes. Zea itself was the largest, capable of housing a significant portion of this fleet.

The Olympius

The Olympias is a remarkable full-scale, working replica of an ancient Athenian trireme, built in Greece between 1985 and 1987.

The project was initiated by the Trireme Trust, founded by historian J.S. Morrison, naval architect John Coates, and writer Frank Welsh. The construction took place at a shipyard in Piraeus, Greece, using Greek ship carpenters.

The design was meticulously based on archaeological evidence, ancient literature, and artistic depictions, particularly the ship sheds (neōsoikoi) discovered at the ancient harbour of Zea in Piraeus.

Due to concerns about longevity and the availability of traditional Mediterranean woods with the required properties, the Olympias was built using Iroko hardwood (a teak-like wood from Africa) for the keel, Oregon pine (Douglas fir) for the planking, and Virginia oak for the frames and tenons. Approximately 20,000 wooden wedges and 17,000 handmade brass nails were used in the construction.

The crucial hypozomata (strong bracing ropes running the length of the hull to provide rigidity) were replaced with steel cables for economic reasons, as natural or synthetic ropes with the same elastic modulus as hemp were unavailable or too expensive. This decision later presented challenges due to the differing tension of steel compared to natural fibres.

The Olympias closely matches the estimated dimensions of a classical Athenian trireme with an overall length of approximately 37 metres, 5.5 metre beam, a draft of 1.1 metres displacing 70 tonnes.

It features the characteristic three levels of rowers, the upper level (Thranitai with 62 oars), the middle level (Zygita with 54 oars) and the lower lever (Thalamitai with 54 oars).

This requires a crew of 170 rowers, plus officers and deckhands, totalling around 200.

The Olympias is equipped with a bronze bow ram weighing 200 kg, a copy of an original ram found in the Piraeus Archaeological Museum.

It also has two large square sails for cruising when not in combat.

Sea trials conducted in 1987, 1990, 1992, and 1994 demonstrated the Olympias' capabilities.

She achieved a maximum speed of over 9 knots (17 km/h) under oar and could perform 180-degree turns within one minute in a very tight arc.

Increasing Size of Vessels during the Late Iron Age

The size of cargo vessels and warships in the ancient Mediterranean generally increased over this period, particularly with advancements in shipbuilding technology and changes in socio-economic and military contexts. However, this was not always a simple linear progression, and regional variations and specific circumstances also played a role.

During the mid-first millennium BC, different shipbuilding traditions coexisted. Archaic Greek shipwrecks in Marseilles, such as Jules-Verne 7 and 9, attested to a genuine Mediterranean sewn-boat tradition. Within this tradition, ships varied in size, including large ships (like Grand-Ribaud F and Gela 1 of 25 metres in length), medium-sized boats (like Jules-Verne 7 with a length of 5 metres and 1.4 metres beam), and smaller boats (like Villeneuve-Bargemon 1).

Around the same time, the baris-type ships from Thonis-Heracleion (Late/Ptolemaic Periods, 664–30 BC) were fluvio-maritime vessels adapted for river and shallow lagoon navigation rather than open seas. One of the largest barides found, Ship 17, was about 27–28 metres long with an 8-metre beam, and had an estimated tonnage of approximately 112-113 tonnes. Evidence from the Ahiqar scroll that dates to the Persian era (525 – 404 BC) lists foreign merchant ships in a Delta port (probably Thonis-Heracleion) falling into two main size groups: 'small' ships around 40 tonnes and 'large' ones around 60 tonnes.

A significant increase in ship size, both for warships and merchant vessels, is particularly evident in the Hellenistic period. The widespread adoption and development of the mortise-and-tenon joint system, which created a strong internal network within the planking, allowed shipyards to build stronger and larger ships with more elaborate hull shapes and increased tonnage. This technological shift was influenced by historical events like rivalries between Hellenistic kingdoms, leading to an arms race in war galleys. This era saw the development of super galleys with increasing numbers of oar rows at the end of the 4th century BC.

Starting from the penteconter with a length of 30 - 35 metres, biremes from 30 metres, and the trireme with lengths varying from 35 – 40 metres in the Classical period, warships progressed to quadriremes with an estimated length between 40 – 45 metres, quinqueremes up to 45 or 50 metres long, and then super-galleys with six or more rows achieving lengths of 100 metres or more.

These super-galleys rapidly expanded, culminating in the immense four thousand oared galley of Ptolemy IV Philopator, in the late 3rd century BC. Although triremes were relatively light and shallow-drafted (the Olympius replica had a draft of only 1.1 metres), the increase in the number of oar banks signifies a considerable increase in overall size and manpower for these warships.

Syracusia - the largest grain ship of its time

Merchant vessels also experienced a phenomenon of "gigantism" during the Hellenistic period. The Syracusia, designed by Archimedes and built for Hiero II of Syracuse about 240 BC, is highlighted as the largest grain ship of its time, with an estimated tonnage between 2000 and 4000 tonnes. While exceptional, its existence demonstrates the technical capacity of large shipyards of the era. Ships in common use during this period, known as myriophoroi, carried 10,000 amphorae, equivalent to 500 tonnes of deadweight.

The Hellenistic type had a Fatal Flaw

While the Hellenistic type offered good sailing qualities, it also revealed a structural weakness at the keel level. This weakness was attributed to the prominence of the keel, characteristic of the wine-glass cross-section, and the lack of connection between the keel and the floor timbers. Later wrecks found off the French coast, in particular the Pointe de Pomègues, Plane I, Caveaux I, Baie de Briande, and Chrétienne A showed evidence of losing their keels after experiencing a sudden shock.

This flaw was recognised, and attempts were made to eliminate it as we shall see later when we look at the Madrague de Giens shipwreck (75 – 60 BC).

Significant Naval Battles in the Mediterranean during the Late Iron Age

There is no point having an arms race if there is no conflict to try out all those innovations. During the Iron Age, fleets of ships were used to carry troops between land engagements during the Ionian Revolt, the Persian Invasions of Greece, and the Wars of the Delian League. This period also saw three major naval engagements.

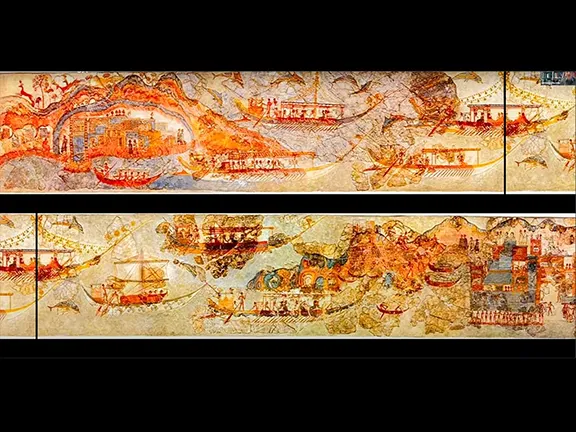

Battle of Alalia between 540 and 535 BC

During the 9th and 8th centuries BC, Phoenicia had established trading posts in Africa and on Sicily, Sardinia and the Iberian Peninsula. The Etruscans emerged as a trading power during the 8th century BC, trading with Corsica, Sardinia and Iberia. They were both partners and occasional rivals of the Phoenicians. After 750 BC, the Greeks began to make incursions into the western Mediterranean colonising Cumae in Italy, Naxos in Sicily and, over the next hundred years, colonies in southern Italy and most of Sicily. Greeks from Phocaea in Turkey established a colony at Marseilles about 600 BC and started to prey on Carthaginian and Etruscan trade to and from Corsica.

The Etruscan and Carthaginian fleets joined forces to beat the Greeks, and the opposing fleets met at Alalia just off the east coast of Corsica. The Phocaean Greeks had 60 penteconters whilst the Etruscans and Carthaginians had about 120. Although the allies defeated the Greeks, they lost half their ships in the battle and the surviving half had to withdraw having suffered severe damage to their rams. It is not known how many ships the Greeks lost.

Battle of Salamis 480 BC

The Battle of Salamis took place during the second Persian invasion of Greece. Salamis is an island in the Saronic Gulf west of Athens. This is generally regarded as the largest naval battle of the ancient world. The Persians, being a land-based power, had assembled a massive fleet of 1,207 ships including triremes, biremes and penteconters from allies and subjugated nations including, Phoenicia, Cyprus, Cilicia, Aeolia, and Lycia. Defending their homeland, the Greek fleet consisted of between 371 and 378 ships, again a mix of triremes, biremes and penteconters.The huge numbers of Persian ships in the confined waters of the Saronic Gulf proved a hindrance to the Persians whilst the Greek ships could manoeuvre with ease. The Persians lost 300 ships whilst the Greeks lost only forty.

Battle of the Eurymedon 469 BC

The Persian and Greek fleets met again off the southern coast of Anatolia in the estuary of the Eurymedon river during the Wars of the Delian League. The Greek fleet consisted of 200 triremes designed by a Greek general called Themistocles. They were long, sleek, and fast and used primarily for ramming operations. The Persians assembled a fleet of between 200 and 900 triremes, depending on whose account you read. The Persian battle line was breached, and the ships were herded into the estuary where they were grounded and subsequently captured and destroyed by the Greeks.

Naval Battles of the Peloponnesian Wars (431 – 404 BC)

The Peloponnesian War saw over a dozen naval engagements as the two main rivals, Athens and Sparta, battled for supremacy. Athens had a dominant navy, while Sparta excelled in land warfare, but they also leveraged naval power from their allies, particularly Corinth. Major naval battles included the Battle of Rhium, where Athenian forces routed a Peloponnesian fleet. Other significant engagements include the Battle of Naupactus, another Athenian victory. The war culminated in the decisive Battle of Aegospotami, where the Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy, effectively ending the war and shifting the balance of power in Greece. Both sides imposed naval blockades to disrupt supply lines, and the Athenian fleet was engaged in a prolonged siege of Syracuse.

In 431 BC, Athens is estimated to have had 300 triremes, whilst Sparta had none. By 405 BC, the Spartans had a fleet of 170 ships when they met the Athenian fleet of 180 triremes at the Battle of Aegospotami. During this final, and greatest naval battle of the Peloponnesian Wars, the Spartans had a decisive victory, incurring minimal losses. The Athenians lost 160 ships and 3,000 of their sailors were executed.

Vying for Naval Supremacy

The ability to deploy significant naval forces and the importance of supremacy at sea during any conflict was not lost on the powers that dominated the Mediterranean. The intermittent Sicilian Wars between 580 and 265 BC involving Carthage and the Greek city states on Sicily, the Wars of Alexander the Great from 336 to 323 BC and those of his successor, Diadochi from 323 to 281 BC, all featured naval engagements, whilst the Pyrrhic War of 280 – 275 BC involved naval movements and control of coastal cities in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas.

As is often the case, hostilities encouraged even more innovation, not least in naval architecture.

Roman Expansion

During the 3rd century BC, a new player entered the arena, Rome. In 264 BC, their expansionist policies brought them into conflict with the Carthaginians. Rome, like the Persians, was a land-based power, faced the naval might of Carthage. The Romans developed their own shipbuilding tradition known as the Western Roman Imperial type, as we shall see in the next article in this series.

References

Bass, G. F. (2011). The Development of Maritime Archaeology. The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology

Hocker, F. M. (2007). Inconspicuous Consumption: The Sixth-Century B.C.E. Shipwreck at Pabuc Burnu, Turkey. Nautical Archaeology, 36(1), 59-77.

Lovén, B., 2011. The Ancient Harbours of the Piraeus, Volume I.1. The Zea Shipsheds and Slipways: Architecture and Topography. Monographs of the Danish Institute Athens, Vol. 15.1.

Lovén, B. and Schaldemose, M., 2011. The Ancient Harbours of the Piraeus, Volume I.2. The Zea Shipsheds and Slipways: Finds, Area 1 Shipshed Roof Reconstructions and Feature Catalogue. Monographs of the Danish Institute Athens, Vol. 15.2.

Lovén, B. and Sapountzis, I., 2019. The Ancient Harbours of the Piraeus, Volume II. Zea Harbour: The Group 1 and 2 Shipsheds and Slipways – Architecture, Topography and Finds. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, Vol. 15.3.

Lovén, B., 2021. The Ancient Harbours of the Piraeus, Volume III.1. The Harbour Fortifications of the Mounichia and Kantharos Harbours - Architecture and Topography. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, Volume 15.4.

Lovén, B., 2021. The Ancient Harbours of the Piraeus, Volume III.2. The Themistoclean Shipsheds in Group 1 at Mounichia Harbour - Architecture, Topography and Finds. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, Volume 15.5.

Raban, Avner. "The Philistines in the Coastal Plain." In The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment, edited by Eliezer D. Oren, 148-182. University Museum Monograph 108. Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 2000.

Rieth, E. (2006). Gyptis: Sailing Replica of a 6th-century-BC Archaic Greek Sewn Boat: SAILING REPLICA OF A 6th-CENTURY-BC ARCHAIC GREEK SEWN BOAT. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 35(1), 5-23.

Pomey, P. et al. (2012). Transition from shell to skeleton in the ancient Mediterranean. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 41(2), 235–314.

Pomey, P., & Boetto, G. (2019). Ancient Mediterranean Sewn‐Boat Traditions. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 48(1), 6-51

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture 2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC  3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC

3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC 4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC

4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC 5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC

5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC 7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD

7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD