Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

Middle Bronze Age Maritime Technology: Aegean, Minoan Crete and Egypt

Middle Bronze Age ship evolution in the Aegean, Minoan Crete alongside Egyptian royal boats and Red Sea harbour evidence (c. 2000-1600 BC).

By Nick Nutter on 2025-04-26 | Last Updated 2025-05-20 | Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 2,906 times

Minoan Seal Ring

Middle Bronze Age Ship Depictions on Crete

The Middle Bronze Age, spanning from approximately 2000 to 1600 BC, witnessed the zenith of the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete. Renowned for its advanced culture and extensive trade networks that stretched across the Mediterranean, the Minoan thalassocracy relied heavily on maritime transport and possessed considerable naval power.

Artistic representations of ships from this period are frequently encountered on Minoan seals and rings, small portable objects that often served as indicators of status or held symbolic significance. These glyptic images, though often small and schematic, provide valuable information about the types of vessels in use during the Middle Bronze Age.

Seals dating to around 2000 BC depict what are classified as Type II boats, characterized by an asymmetrical profile featuring a high stem at one end and a lower extension at the other. This design contrasts with the more symmetrical longboats depicted on earlier Cycladic artifacts, possibly indicating an evolution in shipbuilding techniques or the development of vessels for different purposes. Another seal from Paleocastros, also dating to around 2000 BC, similarly illustrates a Type II ship with a high stem at one extremity and a high extension at the other, suggesting a degree of standardization in this particular vessel type.

Later in the Middle Bronze Age, seals from sites like Mokhlos (MM III) depict Type II ships with curved hulls, a low bow featuring a stempost and spur, and a raised sternpost terminating in a trifurcation. Further examples from Crete (MM I-MM III) show similar Type II ships with curved hulls, a spur and stempost, and a raised sternpost ending in a quadfurcation. A seal from an unknown provenance (MM II) also illustrates a Type II ship with a flat hull, a bow with a stempost and spur, and a raised sternpost with a quadfurcation. These varied depictions suggest ongoing experimentation and regional variations in ship design during this period.

Type III boats, also represented on seals, mark a notable shift towards curved hulls with extremities of roughly equal height. This design represents a departure from the more angular forms of earlier vessels. Additionally, seals dating from 1800-1500 BC in Crete depict Type IV ships, characterized by distinctive crescent-shaped hulls, sometimes adorned with bird symbols and featuring masts with sails.

The appearance of masts and sails in Middle Bronze Age Minoan art signifies a crucial development in maritime technology. A Type III ship representation from Malia (MM IIB) includes a mast supported by three fore and backstays, along with nine oars, indicating the combined use of wind and human power. Similarly, Type IV ship depictions on seals from 1800-1500 BC occasionally feature masts with yards, booms, and sails, confirming the increasing importance of sail propulsion for Minoan vessels. This adoption of sail technology would have significantly enhanced the range and efficiency of Minoan seafaring, facilitating their extensive trade and influence across the Mediterranean. The combination of oars and sails likely provided a versatile means of navigation, allowing ships to take advantage of favourable winds while retaining the option of manual propulsion when needed.

Late Minoan IIIB Larnax (coffin)

Found at Gazi on Crete, the larnax has been dated to between 1300 and 1050 BC. Its decoration included a depiction of a specialised warship with a straight bottom and asymmetrical hull profile.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Middle Bronze Age Ship Depictions in Egypt

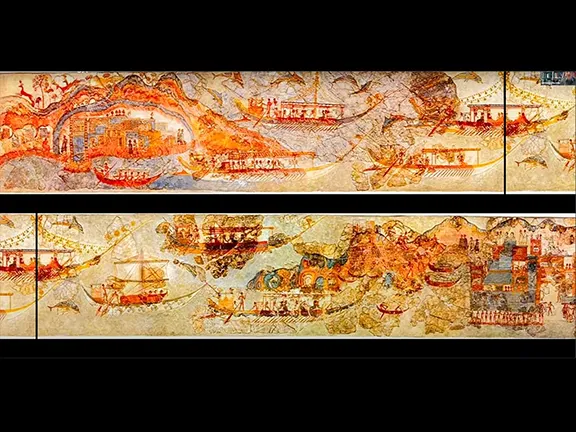

During the Middle Bronze Age, depictions of ships on frescoes within royal tombs became more common.

Tomb of Intefoker at Thebes (Early 12th Dynasty, c. 1985 BC)

The tomb of Intefoker, a high official during the reign of Senusret I, contains fragmented frescoes that include depictions of boats. While these are primarily scenes of riverine transport and daily life along the Nile, they provide context for the broader understanding of Egyptian boatbuilding and navigation skills that would have been transferable to seafaring vessels.

Middle Bronze Age Model Ships

A Meketre model boat

By the Middle Bronze Age, model boats were being produced in the Aegean and in Egypt.

Middle Bronze Age Model Ships from Egypt

Meketre, an Egyptian noble, was buried with models of himself and boats, reflecting his earthly activities and possibly his journey to the afterlife. The models found in Meketre's tomb include travelling boats, sporting boats, and papyrus-like crafts, depicting scenes of travel, hunting, and fishing. All were made during the Middle Bronze Age between 1981 and 1975 BC.

Middle Bronze Age Model Ships from the Aegean

A clay model of unknown provenance, but with characteristics suggesting an Aegean origin, is probably dated to the Middle Minoan I (MM I) period, around 2000 BC. This model is described as an uncluttered type of early Aegean ship, featuring a flat-bottomed hull supported by four feet, one placed at the bow, one at the stern, and two amidship. The vessel has vertical sides that curve slightly inwards at the top, and its bow rises above the level of the gunwale to a pointed end. The unique design of this model, particularly the flat bottom and the presence of feet, distinguishes it from other contemporary ship representations in the Aegean. These features might suggest a vessel designed for navigating specific types of waters, such as rivers or shallow coastal areas, or could represent a regional variation in shipbuilding practices within the broader Aegean maritime sphere. The MM I dating places this model within the early Palatial period of Minoan Crete, a time of significant social and economic change that could have influenced shipbuilding and maritime transport.

Middle Bronze Age Shipwreck off Crete with Evidence of Hull Construction

One wreck is known from the Middle Bronze Age but, again, the timbers and rigging have been consumed by the sea.

Pseira Shipwreck (1725 - 1675 BC) (Middle Bronze Age)

The Pseira shipwreck, discovered off the islet of Pseira in Mirabello Bay, East Crete, dates to the Middle Bronze Age, specifically between 1725 and 1675 BC, based on the Minoan ceramics of the Middle Minoan IIB period found within its scattered remains. Despite yielding the largest known assemblage of complete and nearly complete clay vessels from a single Middle Minoan IIB deposit, no physical remnants of the ship's hull have been found. Therefore, it is impossible to determine the construction methods employed in this vessel. Based on the dispersal pattern of the cargo, the ship has been estimated to have been between 10 and 15 meters in length. As with the Dokos wreck, the Pseira shipwreck, while providing valuable information about Minoan trade and material culture, offers no direct archaeological evidence regarding the shipbuilding techniques of the Middle Bronze Age Minoan civilization. Our understanding of Minoan shipbuilding during this time relies heavily on inferences drawn from other sources, such as artistic depictions found in frescoes and on seals.

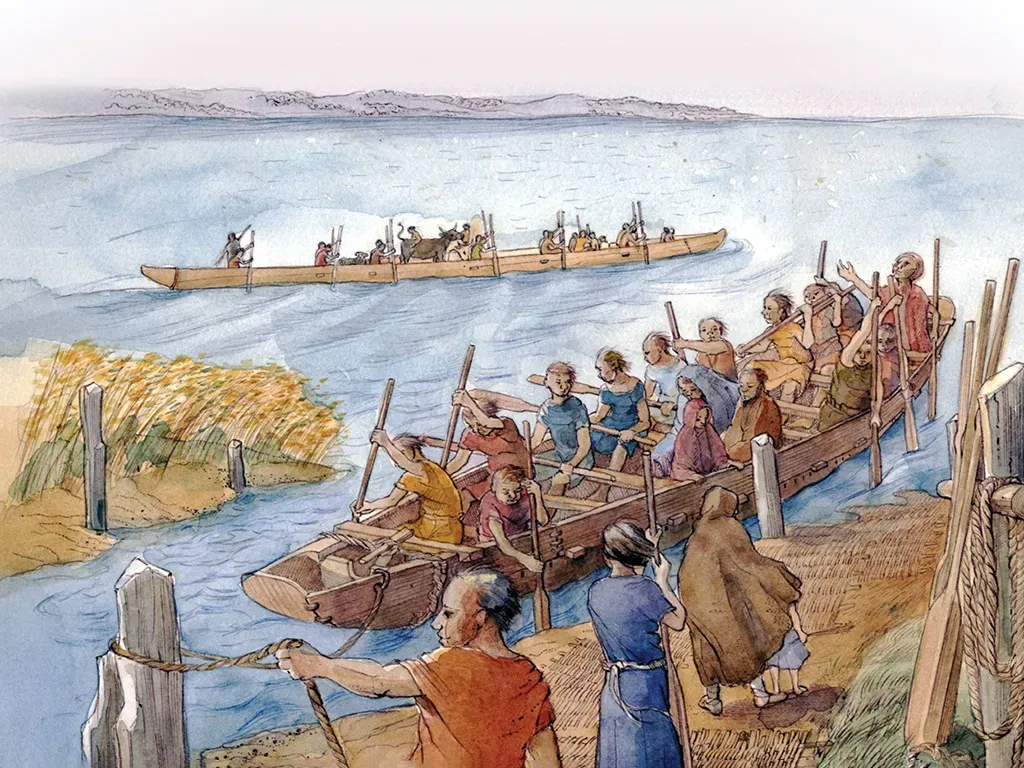

Middle Bronze Age Shipwreck in the Aegean

Aside from the few ship images in models and on seals, a significant find from the early 19th century BC (early Middle Helladic II) comprises the only surviving physical remnants of a small wooden boat, discovered on the coastal islet of Mitrou in the Northern Euboean Gulf. This vessel stands as the earliest actual seagoing boat found in the Aegean, believed to be a locally made fishing boat. Constructed of planks and elongated in shape, it is estimated to have been about 6 metres long and at least 1 metre wide. Gas chromatography suggests oak as a possible construction material. Its features indicate an advanced longboat design with no identified contemporary equivalents in the Aegean or Mediterranean.

Middle Bronze Age Ship Construction in Egypt

Senusret III Solar Boat c 1839 BC

The Egyptians continued to leave boats in tombs to carry the dead to Aaru, heavenly paradise.

Royal Ships of Dashur (c 1839 and c 1814 BC)

The boats discovered at Dashur, specifically near the pyramids of Senusret III and Amenemhat III, are considered to be part of the Middle Kingdom's royal fleet. These boats, dating back to around 1839 BC and 1814 BC respectively, were likely used in religious rituals and potentially for the afterlife.

The Dashur boats, unlike most other ancient Egyptian watercraft, utilized dovetail joints in addition to mortise and tenon joints for construction.

While commonly used in Egyptian furniture and coffins, dovetail joints are rare in watercraft because they lack the structural strength of other joining methods. The Dahshur boats exhibited this feature between the planks, raising questions about their purpose and origin.

Mortise and tenon joints, along with rope lashings, were more typical in Egyptian boat construction, helping to keep the hull planks from separating under pressure. They were used on the bow, stern, and uppermost strake of the Dahshur boats.

The boats were likely built using a plank-first technique, where the hull was formed by adding planks first, followed by other structural elements.

Shipbuilding and Harbours in Middle Kingdom Egypt

Min of the Desert on the Red Sea

Excavations at two sites on the Red Sea coast provide us with further evidence of Egyptian shipbuilding techniques during the Bronze Age.

Mersa/Wadi Gawasis c 2040 BC

Mersa/Wadi Gawasis on the Red Sea coast served as a harbour and staging area for sea voyages, particularly to Punt. While ships were likely built on the Nile and transported as kits, they were reassembled at Gawasis.

The site of Mersa/Wadi Gawasis, also referred to as Saww, was a significant harbour and staging area on the Red Sea coast of Egypt, primarily used during the Middle Kingdom. Archaeological investigations by a Boston University and University of Naples team, beginning with a survey in 2001, have documented its use mainly during this period. According to texts and ceramics found at the site, the complex at Gawasis supported expeditions to Punt and Bia Punt for approximately five hundred years. Excavations have revealed a vast complex featuring carved rooms and galleries.

Excavations since 2004 have identified at least eight such rooms and galleries carved about twenty meters deep into the fossil coral terrace. These spaces incorporated work, habitation, and ritual areas.

The excavations at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis have yielded significant boat building evidence, providing direct insight into pharaonic seafaring in Egyptian ships.

Ship Timbers: Archaeologists uncovered cedar ship timbers at Gawasis, which are riddled with traces of shipworms. The use of cedar indicates that seagoing vessels were built from imported wood.

Construction Techniques: Analysis of the timbers demonstrates that Egyptian ships relied on unpegged, deep mortise-and-tenon joints for hull construction, a technique also used in Nile riverboats. This shows a continuity of shipbuilding traditions between riverine and seagoing craft. Some planks also featured dovetail joints.

Ship Recycling: The site shows extensive evidence of shipbreaking and the reworking of planks after sea voyages. Thousands of pieces of wood debris, cordage, linen fragments, and ship parts with tool marks have been found. Red paint markings on wood suggest inspection and identification of unsatisfactory timbers.

Reused Timbers: Evidence suggests that timbers were reused in other hulls or for architectural features on-site. Ramps within the gallery complex were reinforced with cannibalized ship elements.

Ship Kits: A lengthy inscription documented the construction of ships on the Nile, their dismantling, and transport across the desert as "ship kits" to be reassembled at Gawasis. These kits included planks, beams, and fastenings.

Tools: Large copper-alloy tools such as adzes and chisels, as well as stone tools and wooden wedges, were found, indicating the methods used for dismantling and reworking ships.

Fastenings: Fastenings cut and broken with tools have been discovered. Additionally, evidence for copper straps and ligatures used to reinforce lashing points in the planking has been found. These were locked within channels using wooden wedges.

Rudder Blades and Anchors: Two wooden rudder blades for a steering oar and Egyptian-type stone anchors were among the initial finds.

Plank Dimensions: Hull planks discovered at Gawasis were substantial, with thicknesses of up to 22.5 cm, indicating the robustness required for open-sea conditions. Some thinner planks (2.5-4.2 cm) with small tenon coaks and paired ligature holes have also been found, showing potential similarities to frame fastenings on Greek laced boats.

Ayn Soukhna

Ayn Soukhna, at the head of the Gulf of Suez near the town of Suez, was an important port after the Early Bronze Age. It connected the copper and turquoise mines of Sinai with Memphis, some 120 kilometres west across the Eastern Desert. The site is contemporaneous with Gawasis.

Recent excavations by the Institut français d'archéologie orientale (ifao) have uncovered a facility similar to the one at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis. This site contains stored ship timbers. Like the facilities at Gawasis, Ayn Soukhna had gallery complexes built into the rock.

The facility at Ayn Soukhna likely supported shorter voyages. Evidence suggests these were linked to the direct acquisition of raw materials across the Gulf of Suez and expeditions to the copper mines on the Sinai Peninsula, about a day's sail away. The site features inscriptions documenting these expeditions.

The charred remains of ship timbers discovered at Ayn Soukhna are dated to the Middle Kingdom. These timbers were found tied in bundles and stored in galleries.

Archaeologists have found a number of planks at Ayn Soukhna that are 10 cm thick and up to 23 cm wide. These planks show evidence of both mortise-and-tenon fastenings and lashing channels, similar to the construction techniques used on Nile watercraft.

Min of the Desert

'Min of the Desert' is a full-scale reconstruction of an ancient Egyptian ship built in 2008–2009 as part of an experimental archaeology project. The purpose of this reconstruction was to address questions about the performance, seaworthiness, and reliability of Egyptian seagoing ships, for which basic information was previously lacking.

The design of 'Min of the Desert' relied primarily on archaeological data drawn from timbers excavated at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis and secondarily on contemporary Nile rivercraft techniques. Specifically, the design was based on archaeological data from excavated timbers, representations, models, and river hulls. Consistency in dimensions for components like steering oar blades, beam ends, oar looms, beam spacing, and crutch height, as illustrated in the Hatshepsut Punt reliefs and found at Gawasis, provided the foundation for the vessel's design. Similarities between the profile of Hatshepsut's ships and the Middle Kingdom Dashur boats also informed the design. Naval architect Patrick Couser created the design.

The ship was built at the Hamdi Lahma & Brothers shipyard in Rashid (Rosetta). It was named after the ancient god of Koptos, who is commemorated in almost all of the stelae found at Gawasis. The construction technology used was the same as that of ancient ships launched from Gawasis for voyages to Punt, although modern technologies like electrical band saws were used in some cases for roughing out planks. A crew of four men and two teenagers built the ship, primarily relying on hand tools made to ancient specifications, though of iron rather than the historical copper alloy. Mahrous Lahma and the shipwrights of Chantier Ebad El-Rahman in Rashid were central to the build.

Selected 120-year-old Douglas fir timber was chosen because its properties, including density, bending strength, and ring size, were similar to Lebanon cedar, which was used by the ancient Egyptians but is now endangered. The ship includes exact copies of Gawasis timbers. The ship is held together entirely by unpegged mortise-and-tenon joints along the plank edges. This method followed long-standing Nilotic traditions that allowed vessels to be more easily disassembled and reassembled, transported, and recycled. The plank thickness varies from 22cm for the lowest planks to 14cm at the sheer, sizes that could be manipulated by one or two men with simple tools. In the lower part of the hull, where some seams did not fit perfectly, linen fibres and beeswax were used to fill the gaps between planks.

The dimensions of 'Min of the Desert' are 20m long, nearly 5m wide, and 1.7m deep under the beams, with a cargo capacity of about 17 tons and a 30-ton displacement. Rigging lines and arrangements were designed to mirror those illustrated on the Hatshepsut Punt reliefs. A square sail, measuring approximately 14.25 × 5m, was modelled on the remains of model boat sails and linen fragments.

The reconstruction was almost entirely funded and enabled by the documentary production company Sombrero & Co. Other participants included Arte France, Musée du Louvre, Nova/WGBH, NHK Japan, and the BBC. Kathryn Bard and Rodolfo Fattovich, involved in the Gawasis excavations, helped ensure the reconstruction was based on archaeological data.

Ultimately, the reconstruction, referred to as a "floating hypothesis," demonstrated that the uniquely Egyptian construction techniques, relying on edge-joined thick planks and deep, unpegged mortise-and-tenon joints, resulted in a structurally sound ship capable of effective sailing and seakeeping.

References

Aleydis Van de Moortel. (2017) A New Typology of Bronze Age Aegean Ships: developments in Aegean shipbuilding in their historical context' In book: J. Litwin (ed.), The Baltic and Beyond. Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Gdańsk, September 21-25, 2015 (Gdańsk) (pp.263-268)

Bard, Kathryn A. An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. 2nd ed., Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. (A standard textbook covering Egyptian history and archaeology).

Branigan, Keith. Aegean Metalwork of the Early and Middle Bronze Ages. Clarendon Press, 1974.

Broodbank, Cyprian. An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Gill, Margaret A. V. "Seals and Sealings." A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, edited by Daniel C. Snell, Blackwell Publishing, 2005, pp. 261-281.

Haldane, Cheryl Ward. "Egyptian River Craft and Sea-Going Ships." The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology, edited by Alexis Catsambis, Ben Ford, and Donny L. Hamilton, Oxford University Press,1 2011, pp. 49-70.

Landström, Bjorn. Ships of the Pharaohs: 4000 Years of Egyptian Shipbuilding. Doubleday & Company, 1970.

Tallet, Pierre. "Wadi al-Jarf: An Early Pharaonic Harbour on the Red Sea Coast." Egyptian Archaeology, no. 40, 2012, pp. 40-43.

Tallet, Pierre, and Gregory Marouard. "Iry-Hor et Narmer au sud du Sinai (region de Ayn Soukhna)." Bulletin de l'Institut francais d'archaologie orientale, vol. 101, 2001, pp. 317-327.

Wachsmann, Shelley. Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. Texas A&M University Press, 1998.

Ward, Cheryl. (2010). From River to Sea: Evidence for Egyptian Seafaring Ships. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 2. 10.2458/azu_jaei_v02i3_ward.

Watrous, L. Vance. Crete from Earliest Times Through the Minoan Period. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Zazzaro, Clementina, et al. "The Red Sea in Pharaonic Times: Recent Discoveries at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis." The World of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of John Baines, edited by Robert K. Ritner and Willeke Wendrich, American University in Cairo Press, 2007, pp. 359-374. (Specifically discusses Mersa/Wadi Gawasis).

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture 2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC  4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC

4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC 5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC

5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC 6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC

6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC 7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD

7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD