Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

Late Bronze Age Maritime Technology in the eastern and central Mediterranean Sea

The Late Bronze Age was a period of heightened international trade, diplomatic exchange, and, at times, conflict in the Mediterranean. The Minoan, Mycenaean, Egyptian, and Levantine cultures were key players in this interconnected world, and their artistic representations offer further insights into the ships of the era.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-04-27 | Last Updated 2025-05-9 | Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 3,138 times

Ship Procession Akrotiri. Image: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington

Late Bronze Age Ship Depictions in the Eastern Mediterranean

The volcanic eruption on the island of Thera (modern Santorini) around the mid-16th century BC had a devastating impact on the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri. However, this catastrophic event also resulted in the remarkable preservation of numerous frescoes, providing an unparalleled glimpse into Minoan society, culture, and maritime activities.

Minoan Frescoes from Akrotiri, Thera (c. 16th Century BC)

The "Ship Procession Fresco"

One of the most iconic maritime depictions from Akrotiri is the "Ship Procession Fresco," a miniature painting discovered in the West House. This extensive fresco, measuring approximately 12 meters in length, portrays a procession of seven large, elaborately decorated ships, accompanied by several smaller vessels and a rowing boat, travelling between two distinct coastal towns. The best-preserved of the larger ships in the fresco features a detailed depiction of 20 oars, leading to an estimated length of 35 to 49 meters for this particular vessel.

The primary mode of propulsion for the ships in the "Ship Procession Fresco" is clearly oars, suggesting that the voyage depicted is likely over a relatively short distance between the two visible settlements. The ships themselves are richly adorned with various decorative elements, including depictions of flowers, butterflies, swallows, and symbols drawn from nature. These embellishments strongly suggest that the scene represents a ceremonial event, possibly a seasonal maritime festival or even an illustration from a now-lost epic poem, rather than a routine trading voyage. The presence of dolphins leaping between the ships and the buildings further reinforces the marine setting and adds to the lively atmosphere of the procession.

Beyond the overall scene, the "Ship Procession Fresco" also provides valuable details about the construction and technology of Minoan ships. Features such as ikria, which are interpreted as boat cabins or shelters, are visible on the larger vessels. Additionally, the fresco includes depictions of rigging, offering clues about the use of sails, although sails are not explicitly deployed in the preserved sections of the painting. The level of detail in this fresco underscores the significance of maritime activities in Minoan society and the sophisticated artistic skills of the Theran painters. The depiction of a large fleet suggests a well-organized maritime capability, whether for commercial, defensive, or ritualistic purposes, and the elaborate decorations point to a deep cultural or religious association with the sea and seafaring.

Other Fresco Fragments

While the "Ship Procession Fresco" is the most comprehensive maritime depiction from Akrotiri, other fresco fragments also feature marine motifs, further highlighting the intimate connection between the Minoan civilization and the sea. These fragments, though often less complete, contribute to our understanding of the prevalence of maritime themes in Minoan art and their importance in the daily lives and symbolic world of the people of Thera.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Late Bronze Age Ship Depictions in Egypt

Hatshepsut Voyage to Punt

During the New Kingdom period in Egypt (c. 1550-1070 BC), tombs of pharaohs and high-ranking officials were frequently decorated with elaborate paintings and reliefs that depicted various aspects of Egyptian life, beliefs, and history. Among these, maritime activities and seagoing vessels are often represented, offering valuable insights into Egyptian shipbuilding and seafaring during the Late Bronze Age.

Hatshepsut's Punt Expedition Reliefs at Deir el-Bahari (c. 1479-1458 BC)

While technically reliefs rather than frescoes (carved and then painted), the extensive depictions of Queen Hatshepsut's expedition to the Land of Punt in her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari are crucial for understanding Egyptian seafaring during this time. These detailed scenes illustrate the entire voyage, from the departure of the Egyptian fleet to their arrival in Punt, the acquisition of exotic goods, and their triumphant return to Egypt. Punt was probably at the southerly end of the Red Sea in what is now known as Eritrea so the reliefs illustrate ships that would have sailed the Red Sea rather than the Mediterranean.

The ships depicted in these reliefs are clearly designed for sea travel. They feature a distinctive hull shape, a single, sturdy mast with a large square sail, and two large steering oars located at the stern. The presence of rigging, including stays supporting the mast, is also evident. The vessels are shown laden with incense trees, ebony, ivory, gold, animal skins, and other products of Punt, highlighting the primary purpose of these voyages: trade and the acquisition of valuable resources. The detailed portrayal of these ships provides invaluable information about their construction and capabilities for long-distance sea voyages.

Tomb of Rekhmire (Reign of Thutmose III and Amenhotep II, c. 1479-1401 BC)

The tomb of Rekhmire, a powerful vizier, contains frescoes that depict various aspects of Egyptian administration and foreign relations. Among these are scenes illustrating the reception of foreign delegations bringing tribute and gifts to Egypt. Some of these delegations are shown arriving by sea, and the frescoes include depictions of their ships.

These foreign vessels, often identified as Minoan or Aegean in style, are distinct from the Egyptian ships depicted elsewhere in New Kingdom art. They typically feature different hull shapes, sometimes with high, curved prows and sterns, and are often shown with multiple oars. These depictions highlight the Egyptians' awareness of different shipbuilding traditions in the Mediterranean and their interactions with other seafaring cultures. While not directly illustrating Egyptian seafaring, these frescoes provide context for the maritime landscape of the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean.

Tomb of Kenamun (Reign of Amenhotep III, c. 1390-1352 BC)

The tomb of Kenamun, a high official under Amenhotep III, also contains frescoes that depict foreign tribute being brought to Egypt. Some scenes show ships arriving from the Aegean, carrying goods such as pottery and metalwork. Similar to the depictions in Rekhmire's tomb, these frescoes illustrate foreign seafaring vessels and the maritime connections between Egypt and other Mediterranean powers during the Late Bronze Age.

Tomb of Huy (Reign of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun, c. 1353-1327 BC)

The Tomb of Huy contains facsimile paintings of boats, including "Boat Carrying Captives from Nubia" and "The Viceroy's Boat." While the primary context of the former might be riverine transport related to military campaigns in Nubia, the latter, "The Viceroy's Boat," could potentially depict a vessel used for longer voyages, possibly involving coastal travel or transport along the Red Sea, which was still an important maritime route for the Egyptians. Further analysis of the construction details and the setting of this depiction is needed to definitively classify it as seafaring.

Minoan and Mycenaean Ship Depictions on Seals and Small Artifacts

Minoan Seal Ring

Beyond the grand frescoes and tomb paintings, the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean also yields ship depictions on smaller, more portable artifacts such as seals and pottery fragments. Minoan seals from this period (c. 1600-1200 BC) continue to feature various ship types, including the distinctive crescent-shaped hulls seen in earlier periods, sometimes accompanied by symbolic imagery such as bird figures.

Mycenaean pottery from the site of Kolonna on the island of Aegina, dating to the Late Bronze Age, has revealed painted representations of ships, often in association with depictions of armed men. The inclusion of warriors on these vessels suggests a potential military function, either for naval combat or for transporting troops and equipment.

Late Bronze Age Model Ships

Drawing of Agia Triada alabaster boat

During the Late Bronze Age, we find model ships from the eastern Mediterranean, through for the first time, to Sardinia in the central Mediterranean.

Late Bronze Age Model Ships from Crete

An alabaster model of an uncluttered boat has been discovered at Agia Triada in Crete, dated to the Late Minoan I or LM II period, around 1550-1500 BC. This model, crafted from alabaster – a more valuable material than the clay typically used for earlier models – features an elongated hull with a rounded stern and a curved bow that rises to a point. The use of alabaster at a prominent Minoan site like Agia Triada, known for its administrative functions, suggests that this model might have held a special significance, possibly as a votive offering or an elite symbol. The term "uncluttered" indicates that its design does not conform to the known classifications of Minoan ship types, perhaps representing a unique or specialized vessel.

Late Bronze Age Model Ships from Egypt

Two notable metal ship models were recovered from the tomb of Ahhotep (I) in Egypt, dating to the early 18th Dynasty (c. 1550-1514 BC). One of these is a gold model representing a typical papyriform wood-planked vessel of the Nile. This model provides a valuable point of comparison, illustrating the distinct shipbuilding traditions of Egypt, adapted to the unique conditions of the Nile River. The use of gold underscores the wealth and royal status associated with this funerary offering.

The second metal ship model from the tomb of Ahhotep (I) is crafted from silver and is particularly significant as it closely parallels a contemporaneous Minoan/Cycladic vessel, complete with a crew of ten rowers. This resemblance is specifically noted to the rowed ship depicted in the Miniature Frieze from the West House in Akrotiri on Thera. The presence of this silver model, clearly Aegean in style, within an Egyptian royal tomb is compelling evidence for direct and significant interactions between Egypt and the Minoan/Cycladic civilizations during the Late Bronze Age. This could be attributed to trade, diplomatic exchanges, or even the presence of Minoan artisans or ships within Egypt. The use of silver further highlights the model's value and importance.

Late Bronze Age Model Ships from Sardinia

Late Bronze Age Sardinia also provides evidence of ship models. Nuragic miniature bronze boats featuring Nuragic towers have been found, such as examples from Pipitzu, Orroli, in the Cagliari province, and Badde Rupida-Padria, in the Sassari province. These models, tentatively dated to the Late Bronze Age (c. 1350–720 BC), are interpreted by some scholars as symbols of control over sea routes, reflecting the maritime focus of the Nuragic civilization. The Nuragic towers depicted on these miniature boats are also powerful symbols reproduced in various ways throughout the local Bronze Age, suggesting a potential connection to ancestor cults and local identity.

Late Bronze Age Shipwrecks in the Eastern Mediterranean

Recreation of Uluburun Cargo Hold

Although more wrecks have been found than in any previous period, fine details of their construction are still often lost due to the hostile marine environment.

Kumluca Shipwreck (1600 - 1500 BC)

The Antalya Kumluca shipwreck, located off the western shores of Turkey near Antalya, is dated to the early Late Bronze Age, between 1600 and 1500 BC, based on the style of copper ingots found in its cargo. The vessel, estimated to have been about 14 meters long and 5 meters wide, rests at a depth of 50 meters. While a portion of the hull is visible, it is scattered and largely covered in sediment, which has hindered a comprehensive recovery and analysis of the ship's structure. Consequently, specific details regarding the construction methods of the Kumluca ship are not yet available. The cargo of approximately 1.5 tons of copper ingots, likely originating from Cyprus, suggests a trade route connecting Cyprus with the Aegean. Further excavation and analysis of the hull remains are necessary to gain insights into the shipbuilding technology prevalent in this region during the early part of the Late Bronze Age.

Uluburun Shipwreck (1335 - 1305 BC)

The Uluburun shipwreck, discovered off the coast of Uluburun (Grand Cape) in Turkey, is a remarkably significant find dating to the late 14th century BC (1335-1305 BC). The dating is supported by a combination of evidence, including Mycenaean pottery, an Egyptian scarab bearing the name of Nefertiti, and dendrochronological analysis. Although only a small portion of the hull remained, its analysis has revealed crucial details about Late Bronze Age shipbuilding. The ship is estimated to have been between 15 and 16 meters in length and approximately 5 meters wide. The Uluburun vessel was constructed using planks of Lebanese cedar, a highly prized wood in antiquity, joined together with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints in a shell-first method. This involved creating a watertight outer hull by tightly fitting the planks edge-to-edge and securing them with tenons inserted into mortises and locked with wooden pegs. The ship also featured a proto keel, a thick inboard keel plank that provided additional strength to the hull. Furthermore, evidence suggests the use of the "spigot technique," where the outer hull was constructed before the internal frames and bars were added. Notably, the pegs used in the joinery were not secured with wooden pins, a method later known as "Fenike-mortising" by the Romans. The construction techniques employed in the Uluburun ship indicate a sophisticated level of naval architecture in the Late Bronze Age, suggesting a vessel designed for extensive maritime trade, capable of carrying a diverse and valuable cargo across the Mediterranean.

Cape Gelidonya Shipwreck (c. 1200 BC)

The Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, located off the southwest coast of Turkey near Cape Gelidonya, sank around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. Despite being the first ancient shipwreck to be fully excavated from the seabed, only a few small fragments of the ship itself remained. The vessel is estimated to have been approximately 15 meters long and 4 meters wide. Analysis of these fragments revealed that the Cape Gelidonya ship was built using a carvel construction technique, where pine wood planks were joined edge-to-edge to form a smooth hull. These planks, measuring 10-15mm thick and 5-15 cm wide, were fastened together using mortise and tenon joints secured with pegs. The ship's deck was made of cypress wood. Notably, the wreck also yielded evidence of brushwood dunnage, providing the first real-world example of this practice mentioned in Homer's Odyssey. Additionally, neatly cut dowel holes (1.5-2 cm in diameter) were found in several planks. The discovery of carvel construction in a Late Bronze Age context is significant, as this technique is often associated with later periods. Its presence alongside the use of pegged mortise-and-tenon joints indicates a sophisticated approach to shipbuilding, potentially aiming for a combination of hull strength and hydrodynamic efficiency.

Point Iria Shipwreck (c. 1200 BC)

The Point Iria shipwreck, located off the southern coast of Argolis in the Aegean Sea, dates to approximately 1200 BC, at the end of the 13th century BC, based on the styles of pottery found within its remains. Unlike some other Bronze Age wrecks, no substantial hull remains have been reported for the Point Iria vessel in most sources; it is primarily known from its significant cargo of pottery. The ship is estimated to have been a relatively small merchant vessel, no longer than 10 meters in length. However, one source indicates the recovery of a wooden tenon from the site. It is generally accepted that the Point Iria ship was constructed using the "shell first" method, a technique also seen in the Uluburun and Cape Gelidonya wrecks. The discovery of a wooden tenon suggests that pegged mortise-and-tenon joinery was also employed in its construction. Some interpretations propose that the planking might have been initially sewn together before being joined with mortise and tenon joints. The evidence from the Point Iria shipwreck, while limited regarding hull remains, points towards a shipbuilding tradition in the Late Bronze Age Aegean that likely incorporated both shell-first construction and pegged mortise-and-tenon joinery, potentially with elements of sewn planking.

Modi Island Shipwreck (c. 1200 BC)

The Modi Island shipwreck, situated at the southwest end of the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea, dates to around 1200 BC, corresponding to the Late Helladic III period (13th-12th century BC), based on the style of its ceramic cargo. To date, no remains of the ship's hull have been discovered. The size of the vessel has been estimated by examining the scatter pattern of the cargo, suggesting it was likely larger than the Point Iria ship and approximately the same size as the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, around 7 meters in length. Due to the complete absence of hull remains, the construction methods employed in the Modi Island vessel remain unknown. The ceramic cargo indicates trade connections with Mycenaean centres, but without physical evidence of the ship's structure, any conclusions about its construction would be speculative, though it likely shared similarities with other vessels of the Late Bronze Age Aegean.

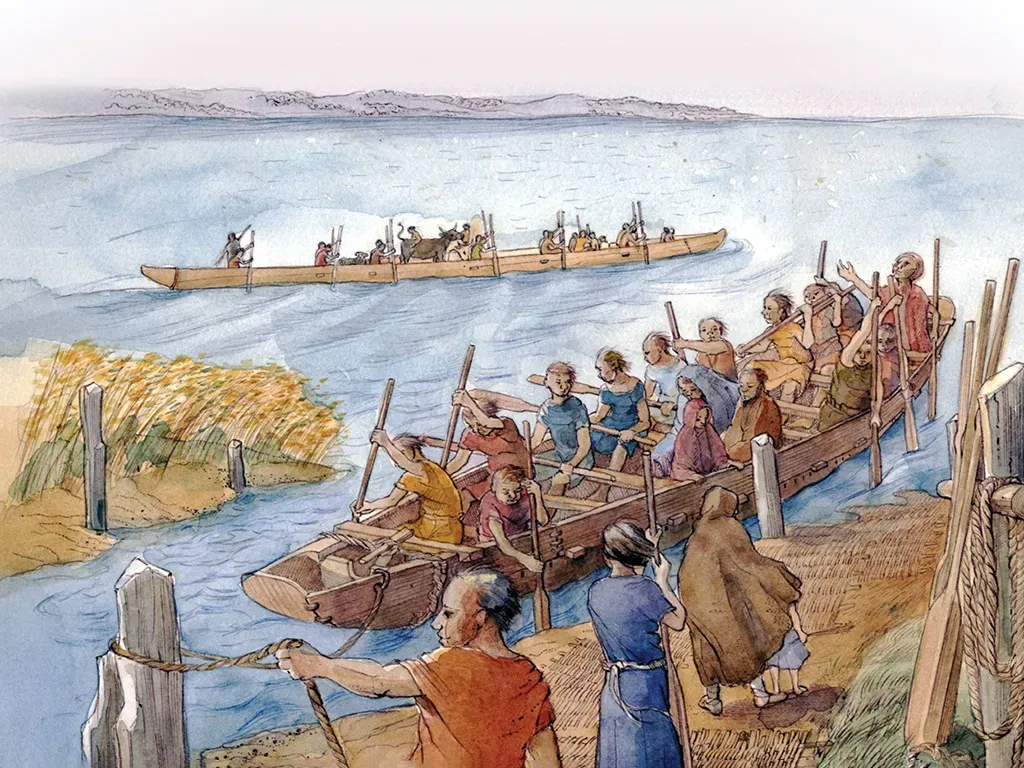

3D representation of Late Bronze Age Minoan Warship

3D representation of Late Bronze Age Minoan Warship. Artist Unknown

New Ships on the Horizon

During the reign of Ramesses II, or slightly earlier, a new design of ship appeared, not just over the horizon, but on pots and in engravings and inscriptions. The features that distinguished it from previous ships included a brailed rig and loose footed square sail, a top mounted crow’s nest, and at least partial decking upon which opposing warriors are shown slinging missiles and brandishing swords. This new design was a significant step forward from the deep hulled cargo vessels that plied the waters of the Mediterranean at this time. It could sail closer to the wind and be rowed. It had sufficient cargo space yet, with a long narrow profile, was light and fast. Unlike laden sailing craft, these galleys could be drawn up on a beach.

This warship was ideal for seaborne raiders, and it may be those people who first set sail in this new ship and that it featured in the sea battles later fought by Ramesses III.

Technology Transfer Bronze Age Style

A heavily reconstructed letter from the Hittite archives at Boğazköi (KuB iii 82) appears to contain a passage where Ramesses II writes to the Hittite king Hattusili III (King of the Hittites from 1267 to 1237 BC). According to this text, Ramesses II evidently planned to send a pair of ships to the Hittite king. He intended to send one ship at that time and another the following year. The purpose of this technology transfer was so that his (Hattusili's) shipwrights could draw a copy of it to build a similar ship.

However, it is important to note that this Akkadian text is heavily reconstructed and contains sizable gaps. Nevertheless, instructions within the letter regarding caulking the ships suggest that Ramesses II did intend for the Hittite king to build seaworthy vessels.

This potential offer is considered remarkable because Hatti was primarily a land empire with a limited association with the sea, relying on coastal vassals for maritime activities. However, the sources also indicate that Hatti began showing more interest in maritime affairs in the later years of the Late Bronze Age, possibly due to the growing threat posed by the Sea Peoples. There are references to Hittite kings dealing with groups like the "Šikala who live on ships" and fighting against hostile vessels. It has been suggested that the ship sent by Ramesses II might have been specifically designed to counter the Sea Peoples or could even have been a captured Sea Peoples ship itself, providing the Hittites with insight into this new threat and its associated technology.

While the correspondence between Ramesses II and Hattusili III is extensive and covers topics such as treaties, marriage, and requests for medical personnel, this particular detail about the offer of ships for copying comes specifically from the interpretation of the heavily reconstructed KuB iii 82 letter.

The warship had arrived in the Mediterranean.

References

Heightened International Trade, Diplomatic Exchange, and Conflict:

Cline, Eric H. (2014). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press.

Sherratt, Andrew, & Sherratt, Susan. (1993). The Mediterranean economy: 3000-700 BC. Journal of European Archaeology, 1(2), 127-175.

Knapp, A. Bernard, & Manning, Sturt W. (2016). Crisis in context: The end of the Late Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean. Journal of Archaeological Research, 24(1), 39-85.

Minoan Frescoes from Akrotiri and the "Ship Procession Fresco":

Marinatos, Nanno. (2000). The Goddess and the Warrior: The Naked Goddess and Mistress of Animals in Early Greek Religion. Routledge.

Morgan, Lyvia. (1988). The Miniature Wall Paintings of Thera: A Study in Aegean Culture and Iconography. Cambridge University Press.

Wachsmann, Shelley. (1998). Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. Texas A&M University Press.

Hatshepsut's Punt Expedition Reliefs:

Naville, Édouard. (1895-1908). The Temple of Deir el Bahari: Introductory Memoir. Egypt Exploration Fund.

Haring, Betsy. (1997). Punt, Oin and the Red Sea. In The Red Sea in Pharaonic Times (pp. 58-73). British Archaeological Reports.

Wachsmann, Shelley. (1998). Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. Texas A&M University Press.

Tombs of Rekhmire, Kenamun, and Huy:

Davies, Norman de Garis. (1943). The Tomb of Rekh-mi-re at Thebes. Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition.

Kamrin, Janice. (1999). The Cosmos of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan. Kegan Paul International.

Minoan and Mycenaean Ship Depictions on Seals and Small Artifacts:

Gill, Margaret A. V. (1965). Minoan and Mycenaean Cylinder Seals. Kadmos, 5(1), 1-23.

Vroom, Joanita. (2005). After Antiquity: Ceramics and Society in the Aegean from the 7th to the 20th Century AD, the Aegean from Late Antiquity Onwards. Archaeopress.

French, Elizabeth B. (1967). Pottery from Late Helladic III B 1 Destruction Contexts at Mycenae. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 62, 149-193.

Late Bronze Age Model Ships:

Casson, Lionel. (1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Basch, Lucien. (1987). Le Musée Imaginaire de la Marine Antique. Institut Hellénique d'Études Maritimes.

Lo Porto, F. G. (1963). La necropoli di Pipitzu di Orroli. Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche, 18, 153-230.

Late Bronze Age Shipwrecks:

Bass, George F. (1967). Cape Gelidonya: A Bronze Age Shipwreck. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 57(8), 1-177.

Pulak, Cemal M. (1998). The Uluburun Shipwreck: An Overview. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 27(3), 188-224.

Van Doorninck Jr., Frederick H. (1991). The cargo amphoras of the Point Iria wreck. In Wrecks and their cargoes (pp. 151-162). Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Beltrame, Carlo. (2012). Boats of the Dead: The Archaeology of Boat Burials. Texas A&M University Press.

Bonino, Marco. (2007). The sewn boat of Zambratija (Croatia): the oldest known example in the Mediterranean. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 36(1), 2-17.

Nautical and Maritime Art in Ancient Egypt Video by Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington

New Ships on the HorizonEmanuel, Jeff. “The Sea Peoples, Egypt, and the Aegean: Transference of Maritime Technology in the Late Bronze-Early Iron Transition (LH IIIB-C) (Aegean Studies 1, Pp. 21-56), 2014.” Aegean Studies 1 (2014): 21–56 . Print.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture 2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC  3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC

3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC 5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC

5: Early Iron Age 1200 - 700 BC 6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC

6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC 7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD

7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD