Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

Early Iron Age Shipbuilding: 1200-700 BC - Naval Warfare, Ship Depictions & Shipwrecks

During the Early Iron Age, new empires were emerging in the Middle East. It was a time of confusion and uncertainty. Naval technology in the Mediterranean took a back seat as maritime trade reverted to local coastal routes traversed by locally built craft using methods learned over millennia. It is also the time when we see the first warships and the appearance of the 'Sea Peoples'.

By Nick Nutter on 2025-05-5 | Last Updated 2025-05-9 | Bronze & Iron Age Shipbuilding in the Mediterranean

This article has been visited 4,014 times

Model of Greek Penteconter

Early Iron Age c 1200 – 700 BC

The bronze age civilisations in the Middle East, the Mitanni, Minoans, Mycenaeans, Assyrians and Hittites, have gone. Only Egypt and the Elamites survived the chaos of the bronze age collapse, both weakened and soon to be conquered by a resurgent Assyria. Surprising survivors, barely affected internally, although they lost much of the bronze age trading network, were the southern Canaanite city states.

From the ashes of the bronze age collapse, the Arameans, Assyrians and the Greeks, began to carve out new territories and redraw the map of the eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, the coastal Canaanite cities, Byblos, Sidon and Tyre, now released from Egyptian dominance, expanded their maritime trading networks west.

It is during this period that we see evidence of the first, purpose built, warships. The first intimation of naval warfare between warships occurs about 1180 BC, the Medinet Habu reliefs showing a battle between Egyptian and ‘Sea Peoples’ naval forces. The second occurs somewhat later when Greek pottery designs included illustrations of Greek warships after 900 BC.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

Early Iron Age Ship Depictions in Egypt

Battle of the Delta - Medinet Habu

Following the collapse of the bronze age civilisations, depictions of ships on frescoes became les common. Archaeological evidence shifts towards other forms of representation, such as pottery and possibly some rock carvings. Egyptian depictions from this period (e.g., the Medinet Habu reliefs showing Sea Peoples' ships) offer some insights, although these represent foreign vessels.

The Reliefs at Medinet Habu

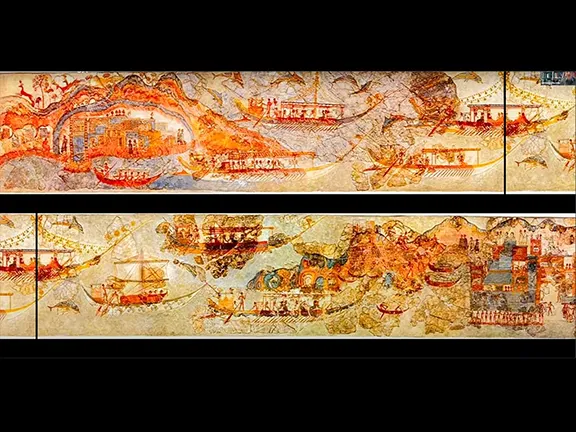

The most detailed depictions of the Sea Peoples' ships in Egyptian art come from the reliefs at the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, dating to around 1180 BCE. These reliefs illustrate the Battle of the Delta, a naval engagement between the Egyptians and the invading Sea Peoples.

The Battle of the Delta 1175 BC

The Battle of the Delta took place around 1175 BC and was a significant naval engagement between the forces of Ancient Egypt, led by Pharaoh Ramesses III, and a coalition known as the Sea Peoples.

The late Bronze Age was a period of widespread upheaval and collapse in the Eastern Mediterranean. Various groups known collectively as the Sea Peoples migrated and raided the coasts of Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt.

Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty faced multiple waves of these invaders. Prior to the Battle of the Delta, he had already fought them on land at the Battle of Djahy in Syria.

The Sea Peoples, whose exact origins remain debated, were a formidable force, and their arrival posed a serious threat to Egypt's stability and survival. They are believed to have been migrants as well as warriors, possibly displaced by the widespread turmoil of the era.

The battle occurred in the Nile Delta, the fertile and strategically important region of Egypt. Ramesses III had anticipated the Sea Peoples' arrival by sea and had prepared a clever ambush.

He lined the shores of the Nile Delta with archers, ready to unleash a barrage of arrows upon the approaching enemy ships. The Egyptian fleet, composed of their own warships, was concealed, waiting for the opportune moment to strike.

As the Sea Peoples' ships sailed into the Delta, they were met with a devastating shower of arrows from the Egyptian archers on land. This likely disrupted their formations and prevented easy landing. Simultaneously, the Egyptian fleet emerged and attacked the Sea Peoples' ships.

The Egyptians employed effective tactics, including grappling hooks to capsize enemy vessels and their more manoeuvrable ships to their advantage in the Delta's waterways.

Depictions on the walls of Ramesses III's mortuary temple at Medinet Habu vividly illustrate the battle, showing fierce hand-to-hand combat on the ships, overturned enemy vessels, and many of the Sea Peoples being killed or captured.

The Battle of the Delta was a decisive victory for the Egyptians. Ramesses III successfully repelled a major sea invasion by the Sea Peoples. This victory is credited with saving Egypt from the widespread destruction that befell many other civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age Collapse.

The battle is considered one of the first well-documented naval battles in history, with detailed depictions and accounts surviving in Egyptian records.

From this point forward, the desire to build bigger and better warships to control the seas was to have a major impact on the design of ships.

Description of Sea People’s Warship

Distinctive Prows and Sterns: The ships are characterized by high, angular prows and sterns. A notable feature is that both the stem and sternposts are typically adorned with bird-head figureheads, often depicted as facing outwards, away from the ship. This is a very distinctive element that sets them apart from contemporary Egyptian vessels.

Curved Hulls: The hulls of the Sea Peoples' ships are shown as being curved.

Raised Decks: They appear to have raised foredecks and afterdecks, providing platforms for warriors.

Steering Oars: Like Egyptian ships of the time, they are depicted with quarter steering oars, located near the stern on either side, for maneuvering.

Masts and Sails: The reliefs clearly show masts equipped with a downcurved yard and a brailed square sail. The presence of brail lines suggests a more advanced method of sail handling, allowing for reefing (reducing the sail area) and better control.

Lack of Visible Oars: Interestingly, in the Medinet Habu battle scene, the Sea Peoples' ships are generally depicted without visible oars being used during the fighting. This has led to some debate. It's possible the oars were stowed during the battle, or perhaps the artists chose not to depict them for clarity or emphasis on the sail power. However, other interpretations suggest these were primarily sailing vessels, possibly relying on speed and manoeuvrability under sail.

Warships: The context of the depiction (a major sea battle) indicates that these were warships, designed for combat and possibly raiding.

Possible Crow's Nests: Some interpretations of the reliefs suggest the presence of crow's nests atop the masts, although this is not universally agreed upon. If present, these would have provided a vantage point for lookouts or fighting.

The Sea Peoples' ships as depicted by the Egyptians, were formidable warships distinguished by their bird-headed prows and sterns, curved hulls, raised decks, quarter steering oars, and sophisticated brailed square sails. The apparent absence of oars in the battle scene remains a point of discussion among scholars. These depictions offer valuable, though potentially somewhat stylized, insights into the maritime technology of these mysterious groups during the late Bronze Age. The depictions of these ships are not dissimilar to the description of the new type of ship that had appeared seventy years earlier during the reign of Ramesses II.

Early Iron Age Ship Depictions in the Eastern Mediterranean

In the mid 20th century AD, archaeologists became aware of a series of rock engravings in the Carmel Ridge area of Israel, particularly around Nahal ha-Mecarot (Wadi el-Mughara) and Nahal Oren. The rock engravings featured what became known as ‘fan-type’ boats. The unique "fan-type" prow suggests a distinct local shipbuilding tradition in the Levant during this transitional period during and immediately following the collapse of the civilisations in the Middle East.

An altar discovered at the harbour site of Tel Akko, dating to the very end of the Late Bronze Age (around the 13th century BC), features engravings of four "fan-type" boats. This provides a relatively secure date for at least some of these depictions.

The Fan-Type Boats of Carmel Ridge

The engravings together depict a boat unique to the area.

Inward-Bending Prow ("Fan"): The most defining feature is the prow, which curves distinctly inward, creating a shape that resembles an open fan or a crescent moon pointing towards the stern. This is where the "fan-type" designation comes from.

Well-Defined "Fan": The curve of the prow is usually quite pronounced and clearly delineated in the carvings.

Stern Features: In some of the more detailed depictions, a tiller and steering oar are visible at the stern, confirming that the "fan" shape is indeed the bow (front) of the vessel.

Masts and Crow's Nests: Some examples of "fan-type" boats in the rock carvings also show masts and even crow's nests at the top of the mast, similar to those seen in some Aegean and Sea Peoples' ship depictions.

Oars (Sometimes): While the "fan" prow is consistent, the presence of oars varies in the depictions. Some carvings illustrate boats with oars, while others do not.

Balawat Gates

Schematically represented Phoenician vessels featuring horse heads (hippoi) on both bow and stern finials bearing tribute are depicted on the Balawat gates of Shalmaneser III, ca. 850 BC. No rigging is shown; instead, they are depicted as being propelled only by oars.

Palace of Sargon II

A wall relief from the palace of the late eighth-century Assyrian king Sargon II (722 – 705 BC) at Khorsabad features similar craft, but with hippoi only at the bows, and with the rowers facing fore instead of aft.

Palace of Sennacherib

The most detailed representations of seagoing Phoenician ships come from the palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh. In a relief depicting the Tyrian king Luli’s waterborne flight to Cyprus in 701 BC, two types of ships are shown: sleek galleys and round hulled merchantmen. The warships feature sharp-edged waterline rams and brailed sailing rigs, while the round ships’ rigging is not depicted. Both feature twin banks of oars and may be intended to represent ships as large as fifty-oared penteconters, although only nine to eleven rowers are depicted per side, as the figures are presented at a much larger scale than the ships.

Early Iron Age Ship Depictions in the Aegean

Siren Vase at the British Museum

Greek Geometric pottery stands out as a significant source for understanding ship styles during the early Iron Age in the Mediterranean. While other cultures also had maritime connections reflected in their ceramics, the stylized yet informative depictions on Greek vessels offer valuable insights into the warships and seafaring of the time.

Geometric Period Pottery (Greece, c. 900-700 BC)

Dipylon Amphorae and Kraters from Athens often feature stylized depictions of ships, particularly warships. They have long, slender hulls and multiple oars, sometimes in multiple banks, inferring biremes or triremes. Many scholars consider the depictions of ships with single banked oars to be early forms of the penteconters. The word ‘penteconter’ itself derives from the ancient Greek word, ‘pentekontoros’, that means ‘fifty oared’. The high, curved prows and stems are shown as somewhat angular but there is no misinterpretation of the ram at the prow that was used for ramming enemy vessels. The ceramics often show troops on the ships, sometimes engaged in combat. Sails are occasionally inferred in a stylistic manner, but the emphasis was on oars as a means of propulsion.

The "Siren Vase" in the British Museum depicts Odysseus tied to the mast of a ship that resembles a penteconter passing the Sirens. The epic poem "The Odyssey," which tells the story of Odysseus, is believed to be set in Mycenaean Greece during the Bronze Age, between 1600 and 1200 BC. The poem itself was likely composed around the 8th century BC. While the events in the story are set during the Bronze Age, the institutions and customs reflected in the poem are more characteristic of the late Geometric or early Archaic period, around 800 BC.

The Penteconter

The word pentēkontoros first appears in one of Pindar’s Pythian Odes, dating to 462 BC. However, the type of ship, a galley rowed by fifty oarsmen, existed much earlier than this first literary mention of the specific word. For example, Homer describes the Phaeacians using such a galley to return Odysseus to Ithaca. Thucydides also believed that the ships used in the Trojan War were principally penteconters and 'long-ships’.

Whilst no remains of a penteconters have been found, researchers have attempted to estimate the size of a penteconters based on the space needed for each rower and the size of the shipsheds that housed the boats. Best guess to date is between 29 and 33 metres in length with a beam of between 3.2 and 5.6 metres.

Shipsheds dating to the Archaic period (800 BC – 500 BC) have been found at Abdera in Greece, and Naxos and Syracuse on Sicily.

Early Iron Age Shipwrecks in the Adriatic

Zambratija Cove Shipwreck

As we move into the Early Iron Age in the Mediterranean, we witness a dearth of shipwrecks. Is this a case of, there are wrecks, but they have not been found, or is it a case of hugely reduced numbers of ships abroad during that time reflecting the uncertainty of the period immediately after the bronze age collapse?

Romano-Illyrian tradition

The Romano-Illyrian tradition is one of two distinct sewn-boat traditions identified in the Adriatic Sea. It is defined geographically, covering the territory from the Danube to the border of the province of Macedonia, encompassing the entire eastern coast of the Adriatic, from north-eastern Istria and Dalmatia to southern Albania.

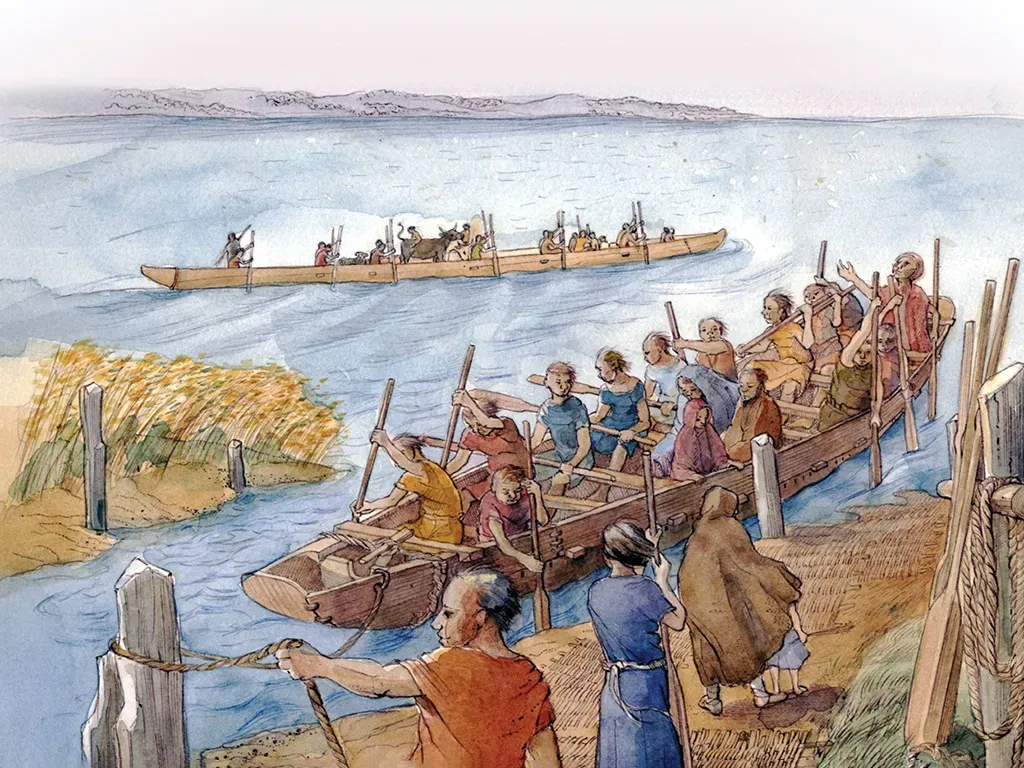

Istro-Liburnian shipbuilding tradition: The Liburnian people, who inhabited the northeastern Adriatic coast between the 10th and 8th centuries BC, had a distinct seafaring tradition that likely took root in this period along with an Istro-Liburnian shipbuilding tradition. Archaeological evidence, such as the sewn boat discovered in Zambratija Cove, Istria, dating back to 1120-930 BCE, suggests a long-standing shipbuilding tradition in the region that predates the full emergence of the Romano-Liburnian Shipbuilding Tradition as described in the next article looking at the Late Iron Age.

Archaeological research in Istria and Dalmatia has revealed nine sewn-plank boats belonging to the north-eastern Adriatic or Istro-Liburnian sewn-boat tradition. Even without specific evidence for the period between the Bronze Age and the Roman Empire, it seems likely that this sewn-boat tradition was continuous. Latin texts by Varro and Verrius Flaccus also refer to the 'rush-rope boats' (serilia naves) of the Istrians and Liburnians.

Zambratija Cove Shipwreck (c. 1120-930 BC) (Late Bronze Age / Early Iron Age Transition)

The Zambratija Cove shipwreck, located in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Croatia, represents an exceptionally well-preserved vessel dating to the transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, approximately 1120-930 BC. Radiocarbon dating of the boat's timbers has confirmed this timeframe. Remarkably, about 70% of the original hull structure has been preserved, offering a unique glimpse into shipbuilding practices of this period in the Adriatic.

The vessel measured approximately 7 meters in length with a 2.5-meter beam, although it is reconstructed to have been around 9 meters long. The Zambratija boat is the oldest entirely hand-sewn boat discovered in the Mediterranean or Adriatic Seas. Its construction involved carefully shaped planks of elm, alder, and fir, bound together using natural fibres such as ropes, roots, and willow branches, with overlapping sections meticulously sewn together. Thin laths of fir, combined with vegetal wadding and pitch, were used to ensure the seams were watertight.

The vessel likely had no mast and was propelled by seven to nine rowers. The keel was crafted from an elm log. The Zambratija shipwreck highlights a distinct shipbuilding tradition in the Adriatic during the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, where sewn-plank construction played a significant role, offering an alternative to the mortise-and-tenon techniques more commonly found in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Overseas Expansion During the Early Iron Age

Despite the lack of shipwrecks from this period and limited iconographic evidence, we do know that intrepid explorers pushed ever westwards from the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Phocaeans

Herodotus tells us that the Phocaeans were the first Greeks to undertake distant voyages and used their penteconters for long-distance trading ventures.

The Phocaeans were ancient Greek seafarers and traders, renowned for their extensive voyages and the establishment of colonies, particularly in the western Mediterranean. They were known as the first Greeks to undertake long sea voyages and made contact with the coasts of the Adriatic, Tyrrhenia, and Spain.

They hailed from an Ionian Greek city, located in Phocaea (modern Foça, Turkey) that was founded towards the end of the 9th century BC.

Their most notable achievement was the founding of Massalia (modern-day Marseille), a powerful Greek city in southern France in 600 BC. They also founded Emporion in Spain in 575 BC, Aleria on Corsica about 562 BC, and Velia in Italy in 540 BC.

The Phoenicians

Sailing from their ports in the Levant, the Phoenicians managed to push west as far as Cadiz on the Atlantic coast of southern Spain. The city itself was founded by the Phoenicians about 875 BC, although they had probably been exploring the area since about 1100 BC. Carthage on the Tunisian coast was founded about 815 BC.

What Happened During the Early Iron Age?

The early Iron Age saw a discontinuity in naval architecture in the Mediterranean. We do not have any wrecks of cargo boats from the period, and precious little in the way of depictions in frescoes, ceramics and engravings, which may indicate a general lack of naval activity.

From what evidence we do have, it appears as though shipbuilding design and architecture in the Levant, Adriatic and Central Mediterranean reverted to long established methods of construction immediately after the bronze age collapse.

Some of the more sophisticated techniques, such as pegged mortise and tenon joints and sewn plank construction used to build late Bronze Age ships, were carried on by the Egyptians, the Greeks, and later by the Liburians in the Adriatic, preventing those techniques from being entirely lost.

One wonders whether the similarity of certain features between boats depicted at Medinet Habu and those shown on the ‘fan type’ boats in the Levant, i.e. possible crow’s nests, lack of oars, are evidence that the Sea People’s ships originated in the Levant.

We also see, during this period, the first depictions of ships engaged in battle and the first intimations that vessels were being designed and built to fulfil a more aggressive role than simply carriers of cargo. The naval ‘arms race’ was beginning.

Iron Age Shipyards on Dana Island

Whilst evidence of ships is lacking during this period, a significant discovery of a shipyard throws some light on naval activity during the Iron Age.

The archaeological discoveries on Dana Island, located off the coast of Rough Cilicia (modern-day southern Turkey), have revealed what is considered the largest and potentially oldest ancient shipyard in the Mediterranean, with significant evidence dating back to the Iron Age (roughly 1200-800 BC).

Underwater investigations and surface surveys on Dana Island have uncovered an astonishing number of nearly 300 rock-cut slipways. This is the largest concentration of ancient naval installations discovered to date, far surpassing other known sites. This vast number suggests a capacity for simultaneous shipbuilding and maintenance on an unprecedented scale in the ancient world.

While the shipyard was likely used in later periods as well, the architectural forms of some of the structures show resemblances to Iron Age masonry, leading archaeologists to believe a significant phase of its use dates back to this period (1200-800 BC). This is a particularly significant finding as archaeological evidence from the Mediterranean "Dark Ages" (following the Bronze Age collapse) is relatively scarce. The Dana Island shipyard provides crucial insights into the maritime capabilities of this era.

The slipways vary considerably in size and characteristics, indicating they could accommodate a range of vessels, from smaller boats to large warships. This suggests a versatile shipbuilding and maintenance facility capable of supporting a substantial fleet.

Behind the slipways, archaeologists have identified various structures interpreted as workshops used in shipbuilding, as well as living spaces, military and religious buildings, managerial facilities, and cisterns for water supply. This indicates a comprehensive naval base and shipyard complex, not just simple slipways.

Dana Island's location in Rough Cilicia, with access to cedar trees in the Taurus Mountains (essential for shipbuilding) and iron ore deposits, made it a strategic location for maritime activities and trade from the Bronze Age onwards.

Some scholars suggest that ships built on Dana Island may have played a role in major sea battles of antiquity, including conflicts involving the Sea Peoples during the Bronze Age and later engagements between Greeks and Persians. The sheer capacity of the shipyard to produce a large number of warships would have had significant political, military, and commercial implications for the Mediterranean.

The shipyard on Dana Island is considered remarkably well-preserved and untouched, offering a unique opportunity to study ancient shipbuilding technology and naval organization.

Archaeological work, including underwater surveys and 3D modeling, continues on Dana Island to further understand the chronology, function, and significance of this extraordinary ancient shipyard. Recent discoveries include evidence of specialized construction for smaller vessels behind the larger slipways.

The Iron Age shipyards discovered on Dana Island represent a groundbreaking discovery in maritime archaeology. Their scale, potential age, and associated infrastructure provide invaluable insights into the naval capabilities and maritime history of the Iron Age Mediterranean, a period that was previously less understood. The site underscores the importance of naval power in the ancient world and the sophisticated logistical operations required to build and maintain large fleets.

References

Artzy, Michal. "Mariners and Their Boats at the End of the Late Bronze and the Beginning of the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean." Tel Aviv 30, no. 2 (2003): 215-30.

Bass, G. F. (2011). The Development of Maritime Archaeology. The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology

Emanuel, Jeffrey P. Seafaring and Shipwreck Archaeology. In Brian R. Doak and Carolina López-Ruiz (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean1. Oxford University Press, 20192. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190499341.013.27

Raban, Avner. "The Philistines in the Coastal Plain." In The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment, edited by Eliezer D. Oren, 148-182. University Museum Monograph 108. Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 2000.

Pomey, P. et al. (2012). Transition from shell to skeleton in the ancient Mediterranean. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 41(2), 235–314.

Pomey, P., & Boetto, G. (2019). Ancient Mediterranean Sewn‐Boat Traditions. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 48(1), 6-51

Ward, C. (2010). "From River to Sea: Evidence for Egyptian Seafaring Ships". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Wachsmann, Shelley. Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1998.

Waterfield, Kathryn. "Penteconters and the Fleet of Polycrates," The Ancient History Bulletin, Volume Thirty-Three (2019), Numbers 1-2, page 1.

Do you enjoy my articles? For your reading pleasure, this website does not carry third party ads. You could help me write more articles by buying me a cup of coffee.

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture

1: Dawn of Naval Architecture 2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC

2: Early Bronze Age c 3000 - 2000 BC  3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC

3: Middle Bronze Age c 2000 - 1600 BC 4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC

4: Late Bronze Age c 1600 - 1200 BC 6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC

6: Late Iron Age c 700 – 264 BC 7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD

7: The Roman Era 264 BC – 400 AD